Slugfest: the story of the epic first battle between Arturo Gatti and Micky Ward

The first bout between Arturo Gatti and Micky Ward took place on this day, May 18, in 2002. The Ring’s Fight of the Year sparked an all-time great trilogy, which was celebrated in a special issue of the magazine (still available via the Ring Shop). Hall-of-fame sportswriter Bernard Fernandez penned the following article, which was originally published in the August 2020 issue.

THE FIRST FIGHT BETWEEN GATTI AND WARD WAS AN INSTANT CLASSIC ON ITS OWN, BUT IT TOOK A BIT OF CONTROVERSY TO ENSURE THAT THE NEXT CHAPTER OF THEIR CELEBRATED TRILOGY WOULD TAKE PLACE

There is a commonly accepted notion that “good things always come in threes,” and so it also is in boxing. The holiest trinity of the so-called “Rule of Three” is the epic trilogy involving heavyweight legends Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier, but there are other passion plays in triplicate that also have reserved places in the pantheon of archrivalries that begin with a memorable original fight and extend through two rematches in which the stakes, bragging rights and places in fans’ collective memories are incrementally raised. History thus has made room at the head table for such revered three-part series as Bowe-Holyfield, Zale-Graziano, Gans-Nelson, Patterson-Johansson, Duran-De Jesus, Gonzalez-Carbajal and Ross-McLarnin.But all of the aforementioned trilogies involved bouts in which world championships were on the line on one or more occasions, and most involved outcomes that included at least one knockout. The lack of those distinctions, somewhat curiously, only serves to elevate what took place on three unforgettable nights from May 18, 2002, to June 7, 2003. During that 13-month period, never-say-die junior welterweights Arturo “Thunder” Gatti and “Irish” Micky Ward took turns putting one another through the kind of 10-round torture tests in which mere boxing talent often takes a back seat to such intangibles as heart, will and a dogged refusal to submit to the standard human frailities of pain and fatigue.

“You dream of fights like this!”

– Emanuel Steward

Ward, who never did give up his blue-collar day job as a steamroller driver for a Massachusetts road crew, put it best: “I picked a hard fucking way to make a living.”

Before Ward and the now-deceased Gatti could march in lockstep to the more cherished annals of their sport, it should be noted that their first fight, widely considered to be the best and most fiercely contested of their trilogy, might not have happened at all, and once it did, it possibly took the pencil of a single judge at ringside to ensure that Acts 2 and 3 would be tacked onto the riveting opening salvo.

As the beloved action hero of HBO Boxing, the then-30-year-old Gatti was unquestionably the “A” side of that mesmerizing first clash, but hints had begun to drop that his bop-’til-you-drop style had already put him on the downhill slope of a career that eventually would gain him posthumous induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2013. He had been outclassed before being stopped in five rounds by the clearly superior Oscar De La Hoya on March 24, 2001, whereupon Gatti’s manager, Pat Lynch, and promotional company, Main Events, decided to make the switch from trainer Hector Rocha to former junior welterweight and welterweight titleholder Buddy McGirt, a slick technician who presumably would smooth some of Gatti’s rougher edges and transform him from unrepentant brawler to something more akin to boxer-puncher. In his first fight with McGirt as his chief second, Gatti didn’t need to show off too many of his more polished new moves as he stopped Terron Millett in four rounds. But he insisted he would reveal the complete package against Ward, a gritty journeyman whose own ring makeup leaned heavily toward the relentless, down ’n’ dirty style the retooled Gatti had vowed to use sparingly at McGirt’s behest.

“Ain’t gonna be no brawl,” Gatti said a few days before he was to meet Ward in the HBO-televised main event at the Mohegan Sun in Uncasville, Connecticut. “I’m going to be moving in and out, and I’m going to beat him up in every round.”

Well, there wouldn’t have been no brawl at all had an agreement not been reached to pair guaranteed box-office and ratings-grabbing attraction Gatti with Ward, a not-quite-first-tier scrapper with a deserved reputation as a tough customer who backed down from no one. Ward was an always-dangerous body-puncher whose most effective weapons were wicked hooks delivered from both the orthodox and southpaw stances.

“Arturo was a superstar,” says Lou DiBella, a former senior vice president of HBO Sports who was involved in staging some of Gatti’s more thrill-packed appearances on the premium cable giant before leaving to form his own promotional company and affiliating with Ward. “Not everyone wanted to admit he was a superstar, because he wasn’t a pound-for-pound guy, but he was like a Rocky Graziano for that period of time, and he put asses in seats.

“Micky was not a fight that Arturo’s people wanted, because they didn’t think there was enough gain for their guy to sustain the kind of pain Micky was apt to bring. They saw it as a high risk, low reward kind of fight. Maybe they didn’t anticipate that hardcore boxing fans got it, that they understood that Ward-Gatti was sure to be a cult matchup.”

Gatti-Ward I matched veteran sluggers who many boxing pundits thought were on the decline.

For his part, Lynch disputes the suggestion that Team Gatti was hesitant to mix it up with Ward, who might have been described at that point as Gatti Lite, a somewhat lesser version of the human highlight reel that the Italian-born, Montreal-raised, Jersey City-based fighter had been in establishing his reputation, win or lose, in instant-classic wars against Wilson Rodriguez, Angel Manfredy, Gabriel Ruelas and Ivan Robinson.

“When Ward got pitched to us, we discussed it,” Lynch says now. “We were comfortable with him as an opponent for Arturo. There was no fear factor on our part. Now, after what happened in that fight, we probably should have known there was something to fear. But going in, we were fine.”

The Gatti side also must have been amenable to site selection in consenting that the event be staged at the Mohegan Sun instead of Atlantic City, where Gatti was the franchise. The New England venue ostensibly made Ward, a sizable underdog, the rooting choice for the sellout crowd of 6,254, although there were enough Gatti supporters there to split support almost down the middle.

The evolving Gatti that McGirt had envisioned was on display in the first two rounds, which he won handily, but the battle was inevitably joined toward the end of Round 3 as Ward, who from the first minute of the first round had to contend with a nasty cut above his right eye, hurt Gatti with some of his signature shots downstairs. “So much for the boxing,” color commentator Emanuel Steward, who no doubt had a suspicion of how the rest of the fight would go, informed HBO viewers.

Despite the spacious 22-foot ring, much of what happened from that point could have been contested in a phone booth as Ward continued to apply constant pressure, obliging Gatti to engage him at close quarters. There was back-and-forth trading, to be sure, but also the kind of abrupt momentum swings that suggested that one determined man or the other was poised to seize absolute control. In each such instance, however, the pendulum soon swung the other way.

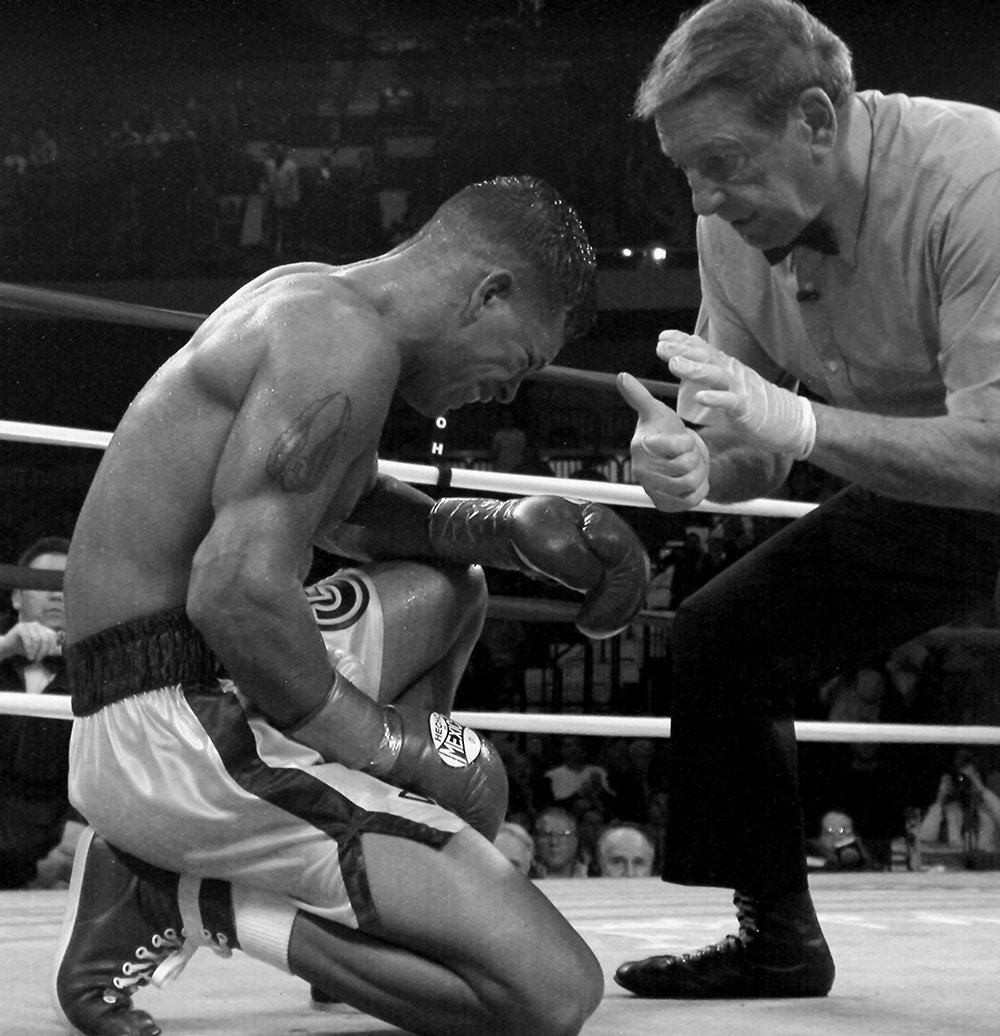

Ward struck with his trademark left to the body in Round 9. Fans are still awed that Gatti got up.

If there were turning points on which the outcome – a majority decision for Ward that conceivably could have gone to Gatti – likely hinged, they occurred in the fourth and ninth rounds, with the frenetic, time-capsule pace of Round 9 moving Steward to exclaim “You dream of fights like this!” and blow-by-blow announcer Jim Lampley, noting that Gatti appeared to be completely spent, to urge referee Frank Cappuccino to “Stop it, Frank! You can stop it at any time! Arturo Gatti’s out on his feet! But Frank Cappuccino’s going to let them keep going!”

Cappuccino also prominently figured in Round 4. Having warned Gatti for a flagrant (but likely unintentional) low blow in the second round, he jumped in and deducted a penalty point from Gatti in the fourth after he floored Ward with a ripping shot that was clearly below the belt. That subtraction proved significant, but no more so than the scorecard submitted by Massachusetts-based judge Richard Flaherty, who gave the ninth round to Ward by an excessively widee 10-7 margin while cohorts Frank Lombardi and Steve Weisfeld each saw it as a more traditional 10-8, given the knockdown. When all the numbers were tallied, Lombardi had the fight a standoff at 94-94 while Flaherty and Weisfeld favored Ward by 94-93 and 95-93, respectively, meaning that the close nod for “Irish” Micky would have been changed to a majority draw had Flaherty also scored Round 9 at 10-8.

“No way that should have been a 10-7 round,” complained then-Main Events president Gary Shaw. “That’s a hometown thing.”

Gatti recuperated during the one-minute interval enough to win the 10th round on all three judges’ cards, but McGirt admits he considered stopping the fight late in the ninth as his guy appeared to be in desperate straits. McGirt even had a towel in his hand, prepared to toss it into the ring as a sign of surrender. But something, perhaps Gatti’s reputation for storming back from the brink, kept him from making that throw.

“Arturo was hurt; I won’t lie,” McGirt concedes. “He was crying in the corner. There were tears literally rolling down his face. I’ve never seen that in my life. But he told me, ‘I’m all right, coach,’ and I believed him because, well, he was Arturo Gatti.”

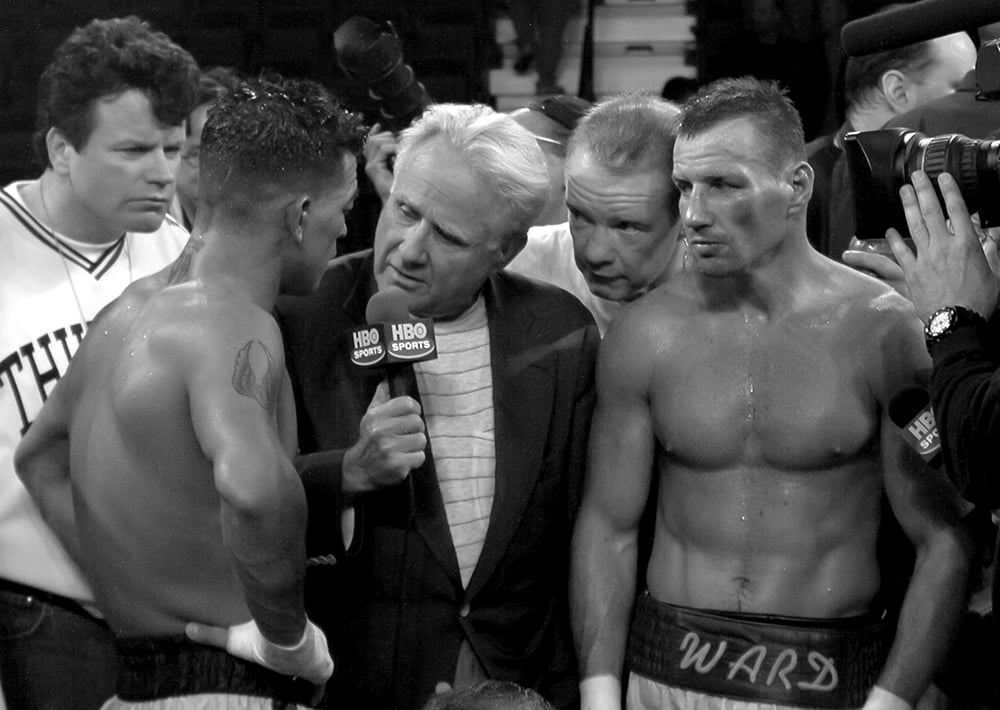

What could’ve been a draw or a ninth-round TKO spawned a great trilogy and a powerful friendship.

Ward’s corner mistakenly misinterpreted McGirt’s body language and the gripped towel late in Round 9 as a signal the fight was over, moving Ward to prematurely celebrate. It was up to Cappuccino to emphatically tell him, “Whoa! Whoa! The fight ain’t over! Last round! Go back to the corner – all the way back!”

Ward came away with the biggest victory of his career anyway, but the timekeeper allowed maybe a half-minute to come off the round clock as Cappuccino excitedly issued Ward those instructions, lost seconds that might have been crucial to Gatti’s chances of registering the knockdown he would have needed to reclaim the upper hand on the scorecards. It is a question that wasn’t answered then and never will be.

But a reflective Lynch now says that, as things turned out, it was providential that Flaherty scored the ninth round as he did, because if he hadn’t, there might not have been Gatti-Ward II and III.

“If it wasn’t for that, I never would have agreed to a second fight with Micky,” Lynch says. “And without a second fight, there would not have been a third. Back in the dressing room after the first fight, Arturo told me, ‘Do you remember me telling you that the toughest fight of my life will be when I fight someone just like me? Well, tonight I fought somebody just like me.’”