The Perfect Storm

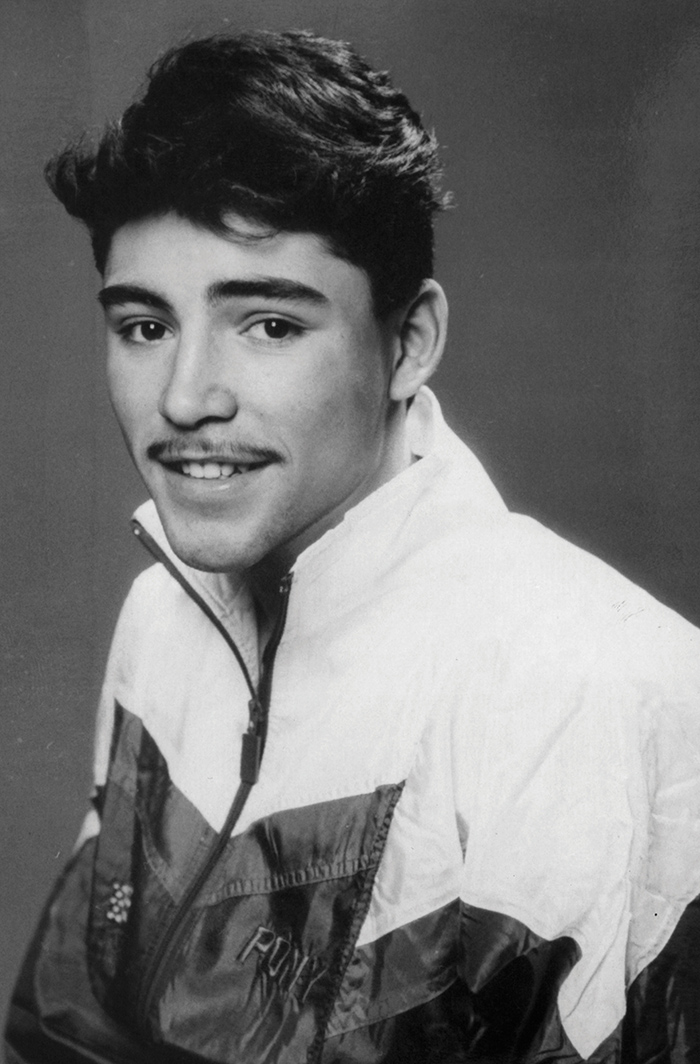

In celebration of Oscar De La Hoya’s 50th birthday, RingTV is re-posting select articles from the September 2022 issue of The Ring, our special edition celebrating the The Golden Boy’s career. The following article, by former Editor-In-Chief Michael Rosenthal, examines what made De La Hoya a transcendent superstar.

DE LA HOYA’S ACCOMPLISHMENTS IN THE RING WERE HALL OF FAME-WORTHY, BUT TALENT ALONE ISN’T WHAT MADE HIM ONE OF THE MOST POPULAR BOXERS OF ALL TIME

Former HBO executive Mark Taffet was chatting with former heavyweight champion George Foreman on a New York-bound train during a promotional tour for Big George’s fight against Tommy Morrison in June 1993.

The conversation centered on pay-per-view, which was in its infancy at the time.

“I wish I were 10 years younger,” the 44-year-old Foreman said. “The pay-per-view boom is going to change the sport. And do you know who’s going to benefit from that?” He paused and pointed. “That kid sitting a few rows in front of us.”

That kid was Oscar De La Hoya, who was scheduled to face Troy Dorsey in his eighth fight on the Foreman-Morrison card. And Foreman was right about him.

De La Hoya would become the pretty face of boxing after Mike Tyson began to decline a few years later, which translated to international fame and a fortune in earnings largely as a result of pay-per-view.

What was it about De La Hoya that catapulted him to that position? What did he have that others at the time didn’t? The appropriate question might be, “What didn’t he have?”

Let’s take an inventory of his assets:

He was impossibly good-looking, which attracted a new demographic to boxing: women.

He was a 1992 Olympic gold medalist when that still meant something among mainstream sports fans. Hence, his enduring nickname, “The Golden Boy.”

He had a compelling backstory, promising his dying mother that he’d win an Olympic championship and then dedicating it to her after she was gone.

He was bilingual, a key element in his ability to become a crossover star in the English- and Spanish-speaking markets.

His timing was good. He arrived around the time the Latino market was starting to boom.

He had one of the greatest promoters of all time, Bob Arum, who, with his team, put all the elements together to build a superstar.

And he had the quality necessary to make all of the above relevant: He could fight. He won major titles in six divisions and was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2014.

Call De La Hoya the “perfect storm.”

“Oscar was Mexican-American,” said Taffet, who would become HBO’s pay-per-view guru. “He came onto the scene with an Olympic gold medal at just the time that Latino population, income and media growth was booming in the U.S. That was the perfect storm. Not only was he an exciting fighter with great accomplishments, he also had consumer and media stages that were ready to be exploited, just as Oscar did.

The boyish Olympian would become The Man as a professional.

“We were truly fortunate to have all that come at the same time.”

Another attractive trait De La Hoya brought to the table was passion that ultimately would inspire his fans and a sense of destiny, both of which were evident from a young age.

Eric Gomez, president of De La Hoya’s Golden Boy Promotions, grew up with his boss in East Los Angeles in the 1980s. He remembers a sixth-grade class assignment in which the students were instructed to write an essay about what they wanted to do for a living and then read it in front of their classmates.

Most of the kids chose typical professions – fireman, police officer, lawyer, doctor. De La Hoya, around 11 at the time, went a different direction.

“I think I wrote that I wanted to be a fireman,” Gomez told The Ring. “Others wanted to be other things. Oscar said he wanted to win a gold medal in the Olympics and be a boxing world champion. All the kids laughed. And the teacher got upset. She felt he didn’t take the assignment seriously and kept him after class.

“I remember seeing him crying. And I remember thinking for the first time, ‘Man, this guy is serious about this.’ I realized then that he had this passion, this dream.”

Gomez remembers another thing about his classmate: The girls were drawn to him.

“He was shy but [the girls] weren’t,” he said. “They were sort of aggressive sometimes because he was a good-looking kid. He definitely caught the girls’ eye.”

That never changed. And Arum and Co. would exploit it to the fullest.

I tagged along on the nationwide promotional tour for De La Hoya’s first fight with Mexican icon Julio Cesar Chavez, in 1996. The then-23-year-old and I shared a van heading from the airport to the next press conference at a hotel in El Paso, Texas. Nothing was out of the ordinary, as the streets were eerily quiet.

Then we turned a corner as we approached the hotel and let out a collective gasp: An estimated 800 people – mostly wide-eyed young women – stood restlessly behind barricades as a few local police officers tried to keep them at bay.

“Every stop he was like a rock star. All I could think of was footage I’d seen as a kid of The Beatles.”

– Mark Taffet

As the van pulled into the parking area and De La Hoya stepped out – maybe 50, 60 meters from the fans – the crowd broke through the barricades and made a mad dash toward the object of their affection. He only had time to yell as he smiled, “Here they come!” before he was enveloped and swept away.

“Every stop he was like a rock star. All I could think of was footage I’d seen as a kid of The Beatles,” Taffet said.

Arum had another story about De La Hoya and El Paso, whose population is around 80 percent Latino.

“I remember in El Paso, at the Sun Bowl,” Arum said. “It was one of these stupid mandatories against a French guy named [Patrick] Charpentier [in 1998]. I thought, ‘How the hell are we going to sell this thing? The French guy is awful.’ And then I looked into the stands and there were at least 50 percent women, young girls, some carrying signs that said, ‘Marry me, Oscar!’

De La Hoya has been dating sportscaster, entrepreneur and model Holly Sonders since the summer of 2021. (Photo by Frazer Harrison/Getty Images)

“We helped in the beginning with that, playing up his looks. I was older than most people in the business. I remembered how Frank Sinatra was sold in the beginning of his singing career. When he opened at the Paramount Theatre in New York, they hired girls to shriek at Sinatra. Then, with Oscar, it took on a life of its own. The women loved him.”

The fact he could communicate fluently in the second language of many of those women – first language, in some cases – shouldn’t be underestimated.

De La Hoya’s parents, Joel Sr. and Cecilia, immigrated to the United States before De La Hoya was born. Thus, they spoke Spanish in the home, unwittingly providing their son with a skill that was valuable in more than one way.

“I really believed that Oscar could become something big the first time I met him,” Arum said. “I saw that the kid was good-looking. And he was fluent in both languages. That was something I hadn’t seen. … Had that happened four, five years earlier, I wouldn’t have paid much attention. But as an eastern guy who had moved out west, I was becoming aware of the overwhelming number of young Hispanics who were fight fans. … It was a whole new audience. He really attracted people to the sport, both Hispanics and English-speaking fans.

“I remember [former head of HBO Sports] Seth Abraham sent me a cartoon he’d seen in The New Yorker. It said something like the ideal man is a combination of Oscar De La Renta and Oscar De La Hoya. In other words, in addition to the huge Hispanic audience he attracted, he worked his way into the mainstream.”

And De La Hoya didn’t speak in two languages just to prove he could do it. He had something to say, which made him a darling of the media and enhanced his appeal.

I attended a number of media days at his Big Bear training camp in the mountains of Southern California, which sometimes attracted dozens of journalists – before the internet age – even though it was a two-hour drive from central Los Angeles.

The television and radio outlets would set up cameras and microphones several meters apart outside his gym and De La Hoya would go from one to the next until everyone was satisfied. And they always were. The shy kid from East L.A. had evolved into a charming, media-savvy young man.

“He always knew the right thing to say,” Arum said. “I would give him a theme as part of the promotion. He could expand on the theme and put it in his own words. And it would come out beautifully. That was real talent.”

De La Hoya (39-6, 30 KOs) also delivered for his fans when it came time to fight.

First, the six-division titleholder avoided no one, even though he was criticized by some early in his career for being protected. More than half of his total fights as a professional were with former or current champions, against whom he went 20-6. Among his victims: Genaro Hernandez, Jesse James Leija, Chavez (twice), Pernell Whitaker, Ike Quartey, Fernando Vargas and Ricardo Mayorga.

“He certainly had all the other attributes,” Arum said. “He just had to be able to fight. And we learned early on that he could. He was a terrific fighter.”

And while he lost a number of his biggest fights – to Shane Mosley (twice), Felix Trinidad, Bernard Hopkins, Floyd Mayweather Jr. and Manny Pacquiao – the excitement and drama he delivered kept the fans coming back.

Even outside-of-the-ring missteps – and there were plenty – didn’t change that. The fans always supported him.

Taffet believes De La Hoya’s absolute peak in popularity came in 1997, when he defeated Miguel Angel Gonzalez, Whitaker, David Kamau, Hector Camacho and Wilfredo Rivera.

“He certainly had all the other attributes. He just had to be able to fight. And we learned early on that he could.”

– Bob Arum

And that busy schedule was no accident. Arum and Co. knew that he was sizzling hot after his passing-of-the-torch victory over Chavez the previous year. They wanted to drive home the notion that he had become the face of the sport, which they accomplished by showcasing him five times in one calendar year.

“I remember Arum spent a lot of time talking about this,” Taffet said. “The master plan. After Oscar won the fight with Chavez, we laid down an aggressive plan to do as many fights as possible in 1997 to permanently establish Oscar as a superstar in the marketplace.

“… That was a specific strategic move that we worked on with Arum. It’s an example of Bob’s brilliance.”

The pay-per-view numbers that Foreman predicted De La Hoya would generate don’t lie. He did 330,000 buys in his first pay-per-view bout, against Rafael Ruelas in 1995. Two years later he and Whitaker generated 720,000 buys. And he peaked at a then-non-heavyweight-record 2.4 million against Mayweather in 2007.

In all, a reported 19 pay-per-view fights generated almost 14 million buys and $700 million. That made him the pay-per-view king until he was dethroned by Mayweather and Pacquiao, who delivered a reported 4.6 million buys and $410 million for their 2015 showdown alone.

Ryan Garcia has the potential to follow in the footsteps of his promoter. (Photo by Tom Hogan/Golden Boy/Getty Images)

Still, when Arum was asked how De La Hoya compared to Mayweather and Pacquiao in terms of his drawing power, he gave a surprising answer: “He was bigger than both of them.”

How is that possible? De La Hoya did have good timing when it came to pay-per-view, as Foreman had suggested. However, it wasn’t perfect timing. The number of homes with access to pay-per-view around 15-25 years ago – De La Hoya’s peak period – paled next to the universe in which Mayweather and Pacquiao met.

In other words, Arum believes that if De La Hoya had hit his peak at the same time as Mayweather and Pacquiao, he would’ve done bigger numbers with the right foil.

“Pay-per-view was just taking off,” he said. “There weren’t as many homes and so forth. Oscar to my mind was a bigger draw on pay-per-view than either Pacquiao or Mayweather. Of course, I could say the same for George Foreman. He did 1.4 [million] against Evander Holyfield in 1991. That was a huge number at the time. And imagine what [Muhammad] Ali and [Sugar Ray] Leonard would’ve done.

“They were all the biggest of their time, though. That’s all you can ask.”

Of course, Gomez could never have imagined what his childhood friend would evolve into, his homework assignment aside. He remembers a low-key boy who sometimes complained that he had to go to the gym rather than play with his friends.

Gomez watched that kid evolve into one of his country’s greatest amateurs, an elite professional and genuine superstar who will remain a central part of boxing lore for as long as people talk about the sport.

Even now, 14 years after his retirement and well into his second career as a promoter, everyone over a certain age knows Oscar De La Hoya.

“He’s still very popular,” Gomez said. “When he goes to any boxing event, in Vegas, in any fight town, they still cheer him on. The kids might not know, but their parents do. He’s one of those rare people, like Ali, Leonard, international stars. They all have that transcending appeal. Oscar has that.

“That little kid had a dream and stuck to it and worked for it. That’s special.”