Ringside: Great Punchers are Great Fighters

One of Julian Jackson’s most celebrated (and chilling) one-punch knockouts took place 32 years ago today. On November 24, 1990, Jackson zapped Herol Graham with a “one-hitter-quitter” in the fourth round of their showdown for the vacant WBC middleweight title.

To commemorate this all-time great KO please enjoy reading Jackson’s foreword to The Ring’s 100 Greatest Punchers (of the last 100 years) special issue (which is still on sale at the Ring Shop).

I want to thank the editors of The Ring for ranking me among the best punchers of the last 100 years.

I’m honored to be in the top 10. Without seeing the other names, I already know that I’m in the company of all-time great fighters.

Great punchers are great fighters. They don’t always get credit for being great fighters, but to be a great puncher, one has to have a lot of boxing ability.

My career is proof of that even though my skills were overlooked when I was fighting.

Most of the time, the knockout punch is a punch the opponent doesn’t see coming.

It’s like that with most KO artists because the ability to punch often hides a fighter’s ability to box. Everybody loves the knockout, but people look past how the fighter is able to knock out his opponent. It doesn’t just happen. Your timing has to be on point. You have to be a split second ahead of your opponent. That’s often the difference between a punch that lands and a punch that ends the fight.

With me, everybody remembered the knockout punch because it was usually sensational. I could tell when I hit a fighter if it was over or if it took three or four rounds out of him and it was time to step up my pressure.

When I landed the shot I was looking for, I felt it, like a shockwave going up to my elbow, and I knew that was it. He was not going to get up.

It was that way with Terry Norris. And Buster Drayton. And Herol Graham. And many others.

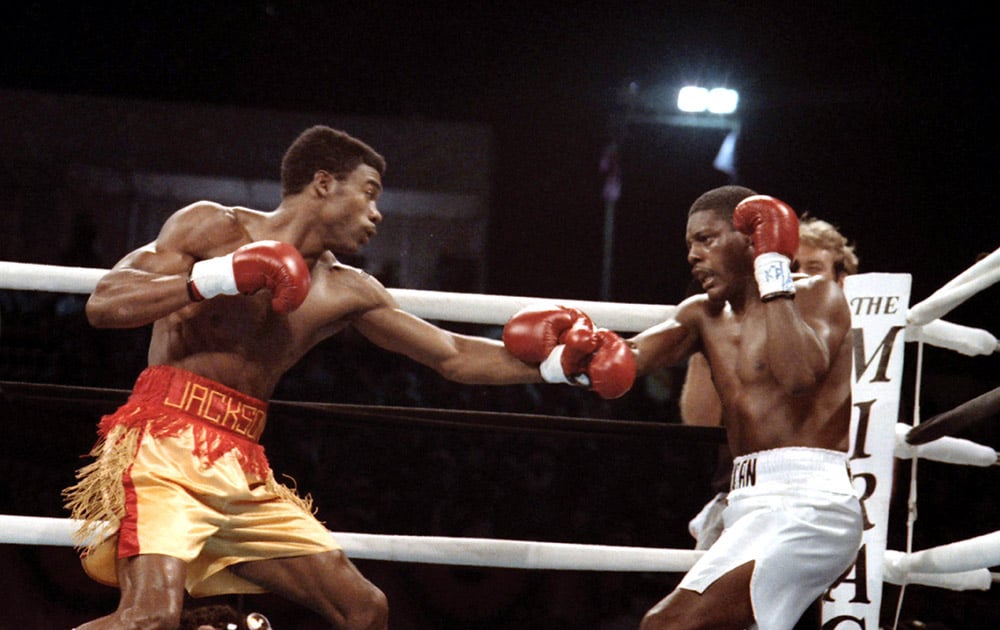

Being on the receiving end of Jackson’s punching power was not a pleasant experience for Dennis Milton, who lost their 1991 middleweight title bout by first-round knockout. (Photo: The Ring)

But most people missed the setup for the punch that ended those fights.

I got to Norris because I had studied him. He was a cocky up-and-comer with a classic American stick-and-move style. We looked at tapes of his fights and knew we had to stay on top of him. When he made a mistake, I knew I had to be in position to take advantage of it. When I saw my opportunity, I caught him flush with a right. It was over as soon as I landed. I didn’t need a follow-up hook and right hand, but I got him with those shots anyway.

I caught Graham because I was well-prepared for his awkward southpaw style. He still gave me trouble for three rounds, but the more confident he got, the more opportunities I had. The moment before I got him, I switched from orthodox to southpaw. I knew if I did that he would come right where I needed him to be, on the left side. He had been catching me with his jab, swelling up my eye, while I boxed orthodox. I used to work out and spar as a southpaw, so I knew I still had the same ability to punch as a lefty. I made the switch with Graham and caught him cold with a right hook.

People see knockouts like that and say, “Julian Jackson is a special puncher.”

But I always felt that my timing was special. I didn’t care how fast you were or how well you moved. I was trained to time my opponent and react at the right moment.

Most knockout punchers have that ability to figure out their opponents’ styles, anticipate their moves and look for the mistakes. That’s when the puncher strikes. Most of the time, the knockout punch is a punch the opponent doesn’t see coming.

They say speed kills, but knockouts come from timing. George Foreman wasn’t fast, but he could hit, and his greatest knockouts came from landing his punches at the right time. John “The Beast” Mugabi could hit, but he wasn’t fast. He had good timing.

I had excellent timing and I was also a very good combination puncher. So I didn’t need to be fast and didn’t worry much about fighting fast boxers, because I was sharp. I learned early in my boxing career that being sharp could beat speed.

Believe it or not, I was a boxer before I was a puncher. I didn’t realize my punching power until late in my amateur career. We just focused on the basics in the gym, the fundamentals, getting our feet in the right position and our hands in the right place. That’s what is most important for boxing and for punching. You have to have the proper form and stance. The mechanics of boxing.

I learned early in my boxing career that being sharp could beat speed.

My trainer told me, “Julian, you don’t have to worry about punching hard; you have a natural ability to punch.” I was told never to try to hit hard. It would come naturally. But I realized as a young amateur that putting my body behind the punches, rotating my hips and shoulders, that helps.

The first time I knocked out a fighter was as an amateur. I was sparring a local professional. His fighting name was Kid Flash. My trainer told me that he’d allow me to work with him even though I was 17 or 18. Still a kid. My trainer told me to just get some work in and not try to punch hard. “Just the basics, Julian, two jabs and a right hand,” he said. Well, I did that and I caught Kid Flash with the right hand flush and he dropped.

It shocked me. I said, “I’m sorry! I’m sorry!” I ran over there and tried to help him to his feet. I asked him for forgiveness. My trainer later told me, “Hey, knockouts are part of boxing. You don’t have to be sorry. It happens. Don’t apologize.” I’ll never forget it. Ever since then, I was given a nickname from a school friend who hung around the gym. He told me, “I’m going to name you The Hawk, because there’s going to be a lot of chickens running from the hawk.”

The name stuck with me and he was right. Once people saw how I knocked guys out, I had a hard time getting the big fights.

I wasn’t as popular as I could have been, because I couldn’t get the big names in the ring. I wanted to fight James Toney when he was middleweight champ. I wanted Roy Jones Jr. when he was coming up. I think politics blocked me and Toney. He was with Bob Arum. I was with Don King. So, we tried to get Roy back when he was still with his dad (as trainer and manager). I heard his father said “No way.” When we went after the other titleholders, I was always told that their managers said there wasn’t enough money for the risk involved.

I really wanted to fight Sugar Ray Leonard. I wanted Leonard so bad. That was a dream of mine because it would have been a game-changer. I thought it might happen after I beat Norris. But Norris got the Leonard fight not long after beating Mugabi (another guy I wanted to fight).

It ticked me off so much that I went to the weigh-in for Leonard-Norris. After Leonard got off the scale, I yelled, “You can’t call yourself a champion when you’re fighting a guy I beat!” He calmly said, “I hear you, Julian, but you know what? You hit too hard.”

So, I guess being a puncher is a blessing and a curse. But it’s mostly a blessing, because boxing celebrates knockouts the way baseball celebrates home runs.

I love Muhammad Ali, looked up to him when I was young, but I was drawn to George Foreman. When he fought, we expected him to land that big punch that would change the fight or end the fight. He did not look as fantastic as Ali looked, but he was just as exciting because of the threat of his power. He had the kind of punches that lifted fighters off the mat!

That’s what people want to see. We respect the boxer but we love the puncher, the guy who puts on a show.

Punchers create excitement. Promoters and managers love to work with punchers because punchers bring in the fans. That’s what it’s all about.

That’s why fans are going to love reading this special issue.

Julian Jackson is a former junior middleweight and two-time middleweight world titleholder who retired in 1998 with a record of 55-6 (49 KOs). He was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2019. He currently works as a coordinator for the amateur boxing program of his native Virgin Islands.