Larry Holmes: Smoke and Butterflies

Editor’s Note: This feature originally appeared in the Larry Holmes Special Issue, which is available for purchase at The Ring Shop.

HOLMES FOUND FRIENDSHIP AND VALUABLE EXPERIENCE AS A SPARRING PARTNER FOR BOTH MUHAMMAD ALI AND JOE FRAZIER

On February 25, 1964, Muhammad Ali stopped Sonny Liston to become the heavyweight champion of the world.

A teenage Larry Holmes had other things on his mind.

“When I was 14 years old, I wasn’t thinking about boxing,” said Holmes. “I was thinking about working and making some money, trying to take care of my family.”

Little did the future hall of famer know what impact “The Greatest” and his fiercest rival, Joe Frazier, would later have on his life. But when Ali, then Cassius Clay, shook up the world, Holmes was a year removed from dropping out of school in order to help his mother, Flossie, and his 10 siblings make ends meet.

“Yeah, man, I can fight.”

Working everywhere from a car wash to fur, steel and rug factories, Holmes’ work ethic was second to none, something that was noticed by ex-boxer Ernie Butler, who took him under his wing at St. Anthony’s Youth Center in Easton, Pennsylvania, and taught him to box. Eventually, Butler got Holmes some amateur bouts, and in 1971, he introduced him to a man who had gone through a lot since that seminal performance in Miami Beach.

Ali, who’d come up short in his quest to regain the heavyweight crown in his third fight after a three-year exile earlier that year, was on the comeback trail following the “Fight of the Century” with Frazier, and he was looking for someone to get some rounds in with him for a charity exhibition to support the PAL in Reading, Pennsylvania, where he was training at the time.

“I’m a young boxer and I’d like to work with you,” said Holmes to Ali.

“Boy, don’t you know who I am?”

“Yeah, I know. That’s why I’m here.”

“I need somebody to work with for an exhibition.”

“OK, I can do it.”

“Can you fight?”

“Yeah, man, I can fight.”

Either impressed by the 21-year-old’s confidence or desperate to have someone to spar with for the crowd showing up for the exhibition, Ali brought Holmes on board and the two traded blows for the first time.

It was the beginning of a relationship that lasted until Ali passed away at the age of 74 on June 3, 2016.

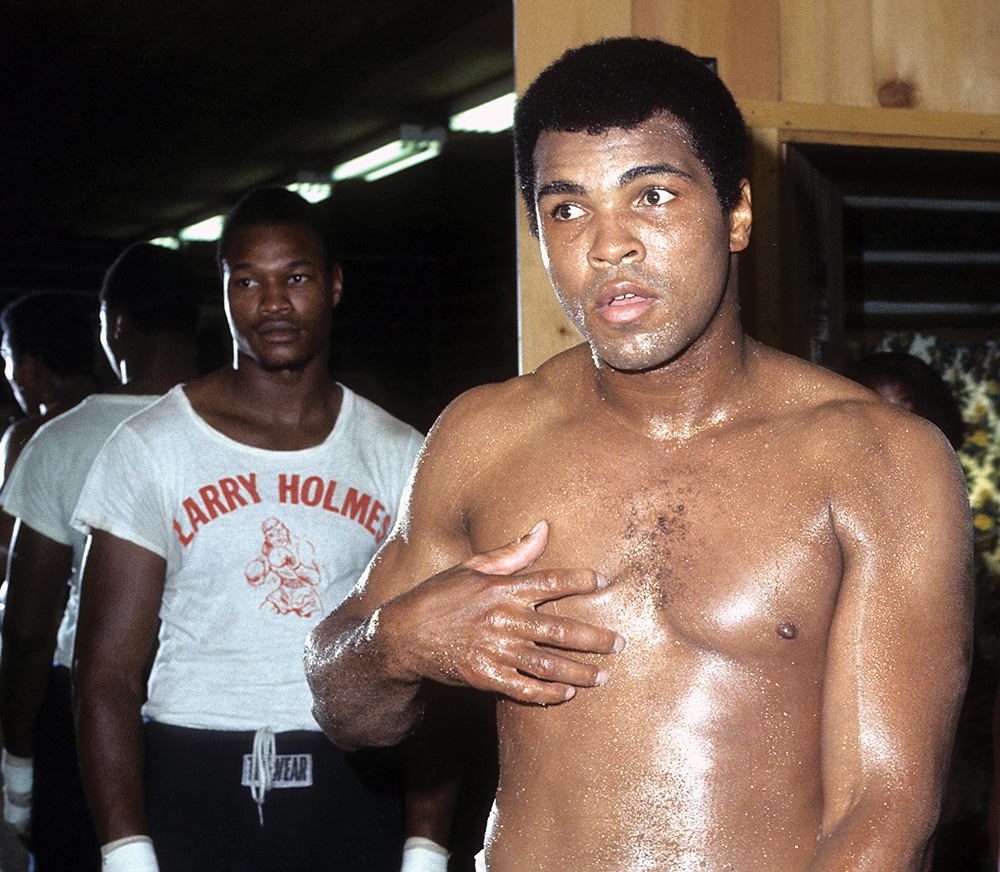

A young Holmes is on sparring duty with Ali at the Deer Lake training camp in 1974.

“I was there to the day he died,” said Holmes. “I always went and seen Ali at the gym, even when he wasn’t fighting. I miss him.”

In December of 2002, Ali and Holmes made a trip to Gallagher’s Steakhouse in New York City to promote the release of a book featuring Ali. It was 22 years after their bout in Las Vegas and even longer from the first time they met in 1971, but watching the two interact made it clear that they were not just work colleagues and then rivals. They were friends. But Ali was still a mentor to Holmes, as evidenced when Holmes was asked about his former boss’ activism and willingness to risk it all for his beliefs, something not many pro athletes at the time were willing to do.

“It was part of his attraction,” said Holmes. “But he never knew if someone was going to shoot him. These days, the best thing you can do is shut up. That’s what their managers tell them: Don’t take no positions.”

Ali interjected.

“They can’t do it because I did it. You’ve got to have the heart to do it.”

Ali had plenty of heart, more than most. But so did Holmes, who was a father of two daughters and trying to earn a spot on the 1972 U.S. Olympic team when he dusted himself off from the exhibition and boldly approached Ali again.

“I was starstruck,” Holmes laughs. “But then I said, ‘Can I work with you tomorrow?’ and he said, ‘Yeah, come on up here.’ He didn’t pay me or anything, but he let me work with him. And he didn’t try to hurt me. I don’t think. (laughs) But he was throwing some punches.”

When Holmes started working with Ali on a regular basis, he would drive home to Easton each day and tell anybody who would listen that he was working with the most famous athlete in the world.

Holmes was put up in a hotel near the gym, but he didn’t stay there that night.

“After I finished working out, I drove back to Easton,” said Holmes, who made the hour-long commute each day until Ali ultimately built his training camp in Deer Lake, Pennsylvania.

“When I got with him and went to his camp in Deer Lake, he was my man,” laughed Holmes. “He couldn’t do nothing wrong.”

Ali completed the Deer Lake Training Camp in 1972, the year Holmes lost to Duane Bobick in an Olympic box-off. That dream shattered, Holmes ended his amateur career with a 19-3 record and turned pro in March of 1973, when he decisioned Rodell Dupree for the grand sum of $63.

Needless to say, money was tight for the young father, but he was able to supplement his fight night wages with paychecks from Ali and another pretty fair heavyweight in Frazier, who was approached in a similar fashion by Holmes when Ali was traveling and not at Deer Lake.

“No one ever called me,” said Holmes. “Joe Frazier never called me; Ali never called me. I just went and told them. I walked into the gym where Joe Frazier was, and I walked into the gym at Muhammad Ali’s camp. One time, Ali was getting ready to fight and he went away. And when he went away, I got in my car and drove down to Philly, and I told Joe, ‘I’m a boxer.’”

“OK, let’s go,” said Frazier. “Get ready.”

“So I got ready and we boxed,” recalled Holmes. “Joe got to liking me and we kept on boxing with Jimmy Young and guys like that. I hung in there with Joe Frazier.”

Considering Frazier’s ferocious left hooks and relentless pressure, that’s saying a lot, but Holmes did tell me in 2020 for an interview with Boxing News magazine that Frazier did catch up to him once.

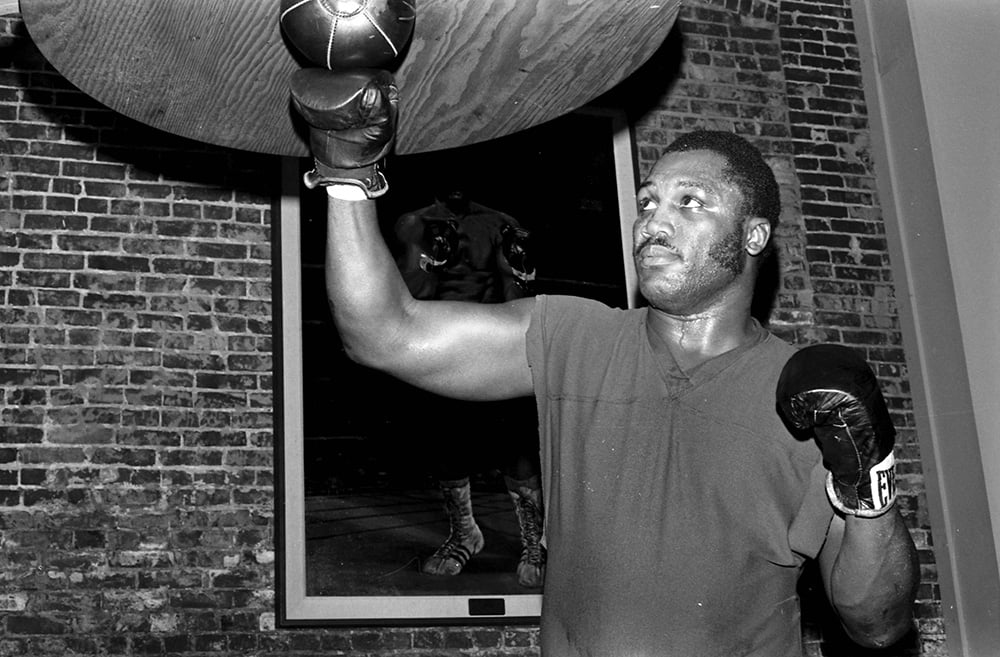

Joe Frazier, seen training in 1974, showed no mercy to the young Holmes in their sparring sessions.

“He used to call me ‘The Roadrunner,’” said Holmes. “I was not gonna stay in there and let Joe bang me up in the ribs and everything. But he caught me one time. One time. He broke my ribs, but I said I ain’t quitting. I’m working with Joe Frazier. I’m not gonna quit.”

Holmes never caught up to the Philly legend in the ring, but as the two joked later, the score is settled.

“Yeah, he got me, but I always told him I got even with him,” recalled Holmes. “Joe said, ‘What do you mean, Larry?’ ‘I knocked out Marvis.’”

Holmes laughs, referring to his 1983 stoppage of Frazier’s son in defense of the Ring title. There were moments of levity between Holmes and his two bosses, but given the animosity between Ali and Frazier at that time, you would imagine that Holmes had to do some fast talking when it was revealed that he was working with both of them. He says that wasn’t the case.

“They didn’t try to switch me in and out,” said Holmes. “There was none of that ‘If you want me, you stay with me.’ None of that. Those guys were professionals. I told Joe I was working with Ali, too, and he didn’t care. Joe wanted the work and to get in shape. That’s all he did. I told Ali I was working with Joe, and he said, ‘What did you do? Did you hit him? Can he take a punch?’ It wasn’t serious about nothing with those two guys.”

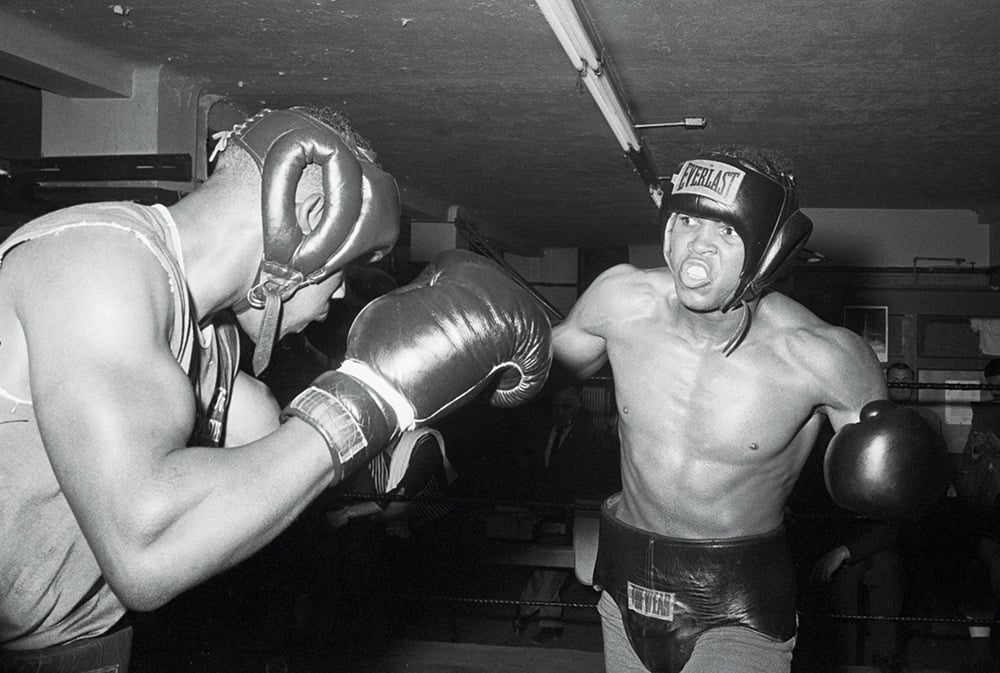

Muhammad Ali (sparring with Cody Jones) was well aware that Holmes was working with his archrival.

As for the actual work, the styles of Ali and Frazier couldn’t have been more different, making it a master class in the sweet science every time Holmes met up with them.

“Ali came out of his dressing room and got in the ring and he did what he did – dance around the ring, and it was shadowboxing,” said Holmes. “Joe didn’t do that. He would shake his hands out and then he’d try to knock you out. That was the way Joe boxed.”

Holmes’ Ali-esque style fit perfectly for Frazier, who would go on to two more bouts with Ali in 1974 and 1975.

“I boxed like Ali – move around the ring, circle around – and Joe liked that,” said Holmes, who fought on the Thrilla in Manila undercard in 1975, halting the brother of Duane Bobick, Rodney, in six rounds. “That’s the kind of work he wanted and that’s what I gave him.”

As for Ali, it wasn’t a surprise that while he had no problem with Holmes picking up a few extra bucks working with Frazier, he had to get in a few jabs – literally and figuratively.

“Ali would get you in the ring sometimes and talk to you,” said Holmes. “He’d go, ‘You’re messing with Joe Frazier. Take that.’ And he would hit me, but I was OK. I was a big boy. (laughs) I took whatever he gave me.”

That’s no surprise; for as pivotal a role as Holmes played in Ali’s preparation, “The Greatest” was even more important to Holmes, in and out of the ring. So he took what he had to while in camp or traveling around the globe with the rest of the team. At first, it was about the money and developing his craft. Later, it became so much more.

“I wasn’t thinking about marketing or anything,” said Holmes, who likely would have been able to parlay a gig as Muhammad Ali’s sparring partner into plenty of lucrative opportunities if the two were fighting in today’s world. “I was thinking about working with him and getting a few dollars every week, and that’s it. And I was there for him. Whatever he wanted or needed me to do. I’d help Lana [Shabazz] in the kitchen. I went to the store. I did whatever he asked me to do.”

And though Ali didn’t sit Holmes down and give advice about navigating the shark-filled waters of the boxing business, his example was much stronger than any words would be. Case in point: When Holmes started working with Ali on a regular basis, he would drive home to Easton each day and tell anybody who would listen that he was working with the most famous athlete in the world.

They weren’t buying it.

“They didn’t believe me,” said Holmes. “Nobody cared. ‘Oh yeah, OK, all right.’ Then I took a couple guys up there with me while I was training, and they watched me fight Ali. Then they started believing me even though I was just an amateur kid.”

Those friends knew the truth, but the rest of the city didn’t. Holmes revealed this to his boss and Ali told him to get ready. They were going to Easton.

“It was like the president walking down the street,” Holmes laughs. “You had a whole bunch of people out there. Ali wasn’t as famous as he would be now, but he was famous, and people recognized him and knew who he was. And they knew I was boxing with him because I made sure everybody knew it, and it was a great time.”

Holmes never forgot that act of kindness, and it showed just who Ali was.

“When we traveled, people stopped and blew their horns,” Holmes told me in 2002. “It was mind-boggling, but I never saw him turn down an autograph. Michael Jordan doesn’t have the charisma Ali has. He won’t deal with you like Ali would. If Ali saw a little kid on the side of the road, he would stop, talk with him and take a picture. Jordan would probably go by and step on the gas.”

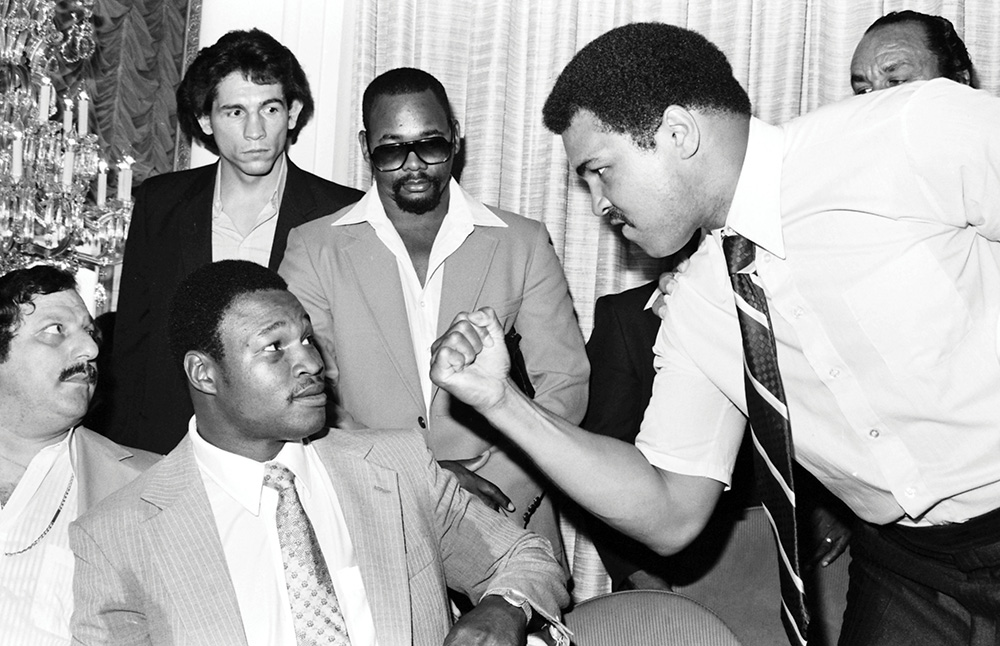

A 38-year-old Ali was unable to bluff Holmes ahead of their ill-fated bout in October 1980.

That’s a hard act to follow for anyone, especially for Holmes, who liked to let his fists do the talking for him. And as he rose up the heavyweight ranks on his own and ultimately won the title in a classic with Ken Norton in 1978, he did it his way, which didn’t sit right with some expecting the second coming of Ali.

“The press weren’t as kind as they are now,” Holmes said. “They said I was arrogant. They said something negative, I said something negative back. I didn’t know how to accept that. It took a lot of maturity. But now they know I’m not as bad as some of the press said I was.”

What they found out was that he wasn’t the next Muhammad Ali, but the first Larry Holmes. That still wasn’t enough for those who cried when Holmes stopped his former boss in their 1980 bout.

“Are you Larry Holmes?” asked one woman who approached the champ on the street after the Ali bout.

“Yes.”

“I hate you.”

“Why?”

“You beat Muhammad.”

Some would never come around, but most did, appreciating Holmes for what he did during a career that saw him compile a 69-6 (44 KOs) record while successfully defending his world heavyweight titles 20 times. That appreciation and respect continues for the 72-year-old, who was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2008 but unfortunately doesn’t have his friends Muhammad and Joe around to enjoy these days with him.

Frazier, Holmes and Norton with actress Barbara McNair in Los Angeles. (Photo by George Rose/Getty Images)

“Ali was a good guy,” said Holmes in 2020. “He let me hang in the gym more than anybody, I think. He treated me well every day until the day he died. He liked me. And I think about Joe a lot. Joe was my man. I learned from both of them.”

When sitting down for this interview in early February, Holmes had just watched a documentary on his buddies the night before, and it brought back memories, and also some new revelations.

“I didn’t realize how much they didn’t like each other, because I worked with both of them,” he said. “Ali was always the man. And Joe was the man when I worked with him. They let me do what I had to do. All they wanted me to do was be there to box when they called me. That’s what they did.”

So he didn’t favor one or the other in their two fights once he started working with them?

“Of course, I wanted Muhammad Ali to win, but that’s it,” Holmes deadpans before throwing the punchline like one of his jackhammer jabs. “I didn’t tell Joe that.”