Eder Jofre remembered: an in-depth look at Brazil’s greatest boxer and his legacy

A few hours after returning from a boxing-related trip this past Sunday night, I logged into Twitter and saw the news that Hall of Famer Eder Jofre had passed away at age 86 due to complications caused by his months-long bout with pneumonia.

In confirming the death on Facebook, Jofre’s daughter Andrea wrote the following: “Dear Fans, friends and family: It is with great sorrow that I inform that my father, our beloved Golden Rooster, all-time boxing world tri-champion, has passed away at the age of 86. (He) left us this morning around 2:20.”

I knew that Jofre had been ill for several months – he and his family was forced to cancel a hoped-for appearance at the “Trilogy” Induction Weekend at the International Boxing Hall of Fame – but the news of his passing still produced pangs of sadness because I had such high regard for him and his story.

The first time I learned about Jofre in detail was when I read a profile of him by then editor-in-chief Nigel Collins in the August 1986 issue of The Ring. The occasion was Jofre’s induction into the magazine’s Hall of Fame – a Hall of Fame that pre-dates the IBHOF by more than three decades – and the following two paragraphs instantly grabbed my attention:

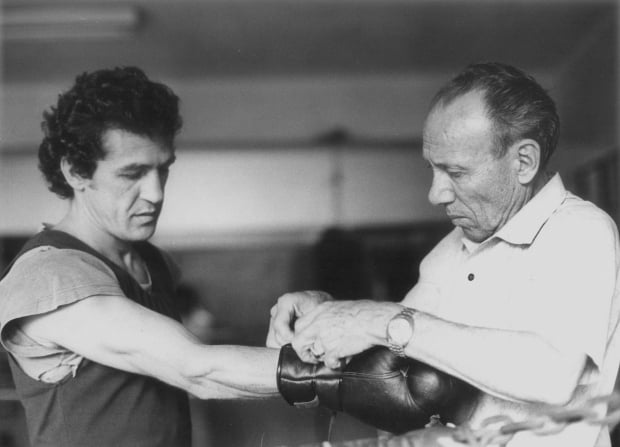

“Standing only 5-feet-4 inches, Jofre was a handsome fellow with a shock of black curly hair. He boxed out of a classic, standup stance with his chin ducked down behind his shoulder. His footwork was economical, but effective. However, it was when he hooked off the jab, or crossed his right, that the secret of his success was truly revealed. Simply stated, Jofre was one of the hard punching bantams to ever lace on the gloves. During one stretch, from June of 1960 until May of 1965, he scored 17 consecutive knockouts – nine of them in world title fights.

“‘Jofre fought a little bit like Alexis Arguello,’ remembers veteran matchmaker Teddy Brenner. ‘A great fighter, a great puncher.’”

I had always been a huge fan of Arguello’s thoughtful, mechanically brilliant style, so Brenner’s comparison to “The Explosive Thin Man” drew me in. But when I learned later in the article that he launched a comeback at featherweight in his mid-30s and dethroned the gifted Jose Legra at age 37, I was sold. I was a fan and I wanted to see for myself if the glowing words ascribed to him were real.

I began collecting videos in January 1986 and one of the first fights I requested in trade was anything on Jofre. Unfortunately, all the complete footage that was available at the time were his two fights with Fighting Harada, the only two losses of his 78-fight career. Even so, the video was enough to show me that at his best, he probably was the best of his era.

In the intervening years, complete footage of his fights with Legra as well as both of his victories against Jose Medel surfaced and I thoroughly enjoyed viewing them. I began writing for The Ring in the late-1980s, a period in which the magazine was experiencing such profound financial issues that they couldn’t afford to pay me in cash. On one occasion, I was asked to request something from their archives in lieu of money. My request: A photo of Jofre. That’s how big a fan I was.

Clad in an Eder Jofre t-shirt, author and historian Lee Groves poses with Chris Smith’s definitive biography of Jofre as well as a personalized autographed photo of Jofre in his home office in Friendly, West Virginia in September 2021.

In recent years, I was able to gain closer access to the legend through Chris Smith, who released the definitive biography on Jofre in 2021 entitled “Eder Jofre: Brazil’s First Boxing World Champion.” He arranged to have Jofre sign my copy of his book as well as secure a personally autographed color photo of him during his prime that still hangs in my home office. I had hoped to meet the man himself in Canastota, but it was not to be. And now, it will never be.

His life in boxing was the stuff of legend, a run of excellence that few have ever produced. He is universally acknowledged as the greatest boxer Brazil ever produced and he was known as “The Golden Bantam” for his splendid technique, supreme ring intelligence and knockout power in each fist. Despite being a bantamweight, he was so highly regarded that he was considered boxing’s best pound-for-pound fighter during his peak in the early 1960s.

It also could be argued that Jofre assembled the greatest comeback in boxing history. Consider: Following a three-year retirement following the twin losses to Harada, Jofre won all 25 fights (13 by knockout), the most significant of which was the off-the-floor majority decision victory over Legra to capture the WBC featherweight championship. At 37 years and 49 days, Jofre remains the oldest fighter ever to win a widely recognized share of the 126-pound title as well as the oldest featherweight titlist to record a successful title defense (he was 37 years 218 days old when he stopped fellow featherweight legend Vicente Saldivar in four rounds). After being stripped by the WBC for not defending against mandatory challenger Alfredo Marcano in a timely manner, Jofre added seven more wins and retired with a record of 72-2-4 (50).

If ever a fighter was bred for the sport, it was Jofre. Born March 26, 1936 in Sao Paulo, Brazil, Jofre’s family lived in the back room of a boxing gym. His father, former boxer Aristides, owned the gym while his mother, Angelina, was one of its employees. Jofre told The Ring’s James Dusgate in the October 1992 issue that 14 relatives made their living from either boxing or wrestling.

“My father’s brother Tonico made his pro debut on (the day I was born),” Jofre told Dusgate. “On my mother’s side, Olga Zumbano was one of the best women wrestlers in the world, Ralf Zumbano was lightweight champion of Brazil and Hans Norbert was middleweight champion of Europe.”

Jofre’s maiden voyage in gloved fisticuffs took place at age four when he fought a cousin and his first semi-organized contest occurred five years later when his father staged a tournament at his gym between members of the Jofre and Zumbano clans. When Eder won the opening contest against his cousin Ricardo Zumbano (who went on to turn pro and produce a 6-4-8 mark between 1957-1961), a joyous Aristides lifted his son skyward. This act of paternal approval as well as the thrill of the combat itself cemented the boy’s love for “The Sweet Science.”

“When they introduced us, I felt a thrill up and down my spine,” Jofre told Smith. “Then the fight began. Here all the nervousness was out of me. I was doing what I wanted to do. It all seemed like something I had done many times before. In other words, I was dream-fighting. And you know what? In the third round, just as I had dreamed, I hit him a hard right hand. Down he went, and he didn’t get up. I had knocked him out. Inside of me, it was as if somebody had lit a fire. I was burning with happiness. My father climbed into the ring and effortlessly lifted me onto his shoulders. I couldn’t have weighed more than 50 pounds. Everybody cheered, while my father danced around with me on his shoulders. But I remembered I had to be a good sport. I made my father put me down, and I went over to my cousin. He had been shaken up, but he wasn’t hurt, and we embraced as he congratulated me on my good fight.”

Jofre’s intense training throughout his youth helped him earn a berth on Brazil’s 1956 Olympic squad. The bantamweight was viewed as a gold medal hope, but after outpointing Burma’s Thein Myint in his opening fight to advance to the quarterfinal, his dream ended one step short of the medal stand after being outpointed by Chile’s Claudio Barrientos.

Jofre turned pro four months and one day later by stopping Raul Lopez in the fifth round of a scheduled eight-rounder, then halted him in three rounds 28 days later. Jofre’s skill level was such that he was moved into a 10-rounder in just his third pro fight, and his 10th round TKO over Osvaldo Perez proved he already had the strength and stamina to maintain his high level of performance over the long haul.

The prospect attributed his success to a dietary decision he made shortly after returning from the Olympics: He became a strict vegetarian.

“Many people at the time said I was crazy,” he told Dusgate in 1992. “The idea wasn’t nearly as popular back then as it has now become — and certainly not for a professional sportsman. But it was a conscious decision on my part; I knew what I was doing. For years I had seen other fighters eat lots of meat and fish, supposedly to give them energy. But after a few rounds of a fight, they would tire just the same. I figured that a diet high in green vegetables and fruit would give me more energy for endurance. And it worked. My diet contributed to me being able to maintain my weight, which was often a serious problem, and fight at bantamweight so long.”

Jofre’s mark after 15 fights was 12-0-3, after which Jofre rolled off 22 straight wins. Not only did he avenge the two draws against Ernesto Miranda (the first by 15 round decision to win the South American bantamweight title and the second by third-round TKO to retain it in his very next fight) he did the same against Ruben Caceres (by seventh-round stoppage in July 1959) while also reversing his Olympic defeat against Barrientos via eighth-round TKO in July 1960 to earn a world title eliminator against 62-fight veteran Joe Medel of Mexico that August 18. The scheduled 12-rounder at the Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles was Jofre’s second appearance outside Brazil and, not for the first time, the scale was as much of an opponent as the man standing across the ring from him. Jofre managed to hit the 118-pound limit on the nose after shedding seven pounds, after which Medel would test the Brazilian’s resolve like never before.

Following a quiet first two rounds, the action picked up considerably in the third when Jofre trapped Medel along the ropes and began a lengthy exchange. The frantic fifth ended with Jofre battering Medel but the Mexican turned the tables late in the ninth when a series of power shots forced the clearly hurt Jofre to retreat. But Jofre suddenly flipped the script by landing a scorching hook to the jaw just before the bell. Medel tried his best to recover but Jofre’s relentless attack proved too formidable. Just before the bell, a right uppercut to the jaw followed by a right-left-right left Medel in a semi-fetal position on the floor. After the bell sounded, Medel’s seconds raced into the ring, dragged their charge back to the corner and tried to revive him in time for the start of round 11. Because they couldn’t, Jofre was declared the TKO winner.

“This fight was the most remarkable for me because it was the first time a Brazilian boxer made it to the world championship fighting in the USA, and it was a hard fight,” Jofre told Smith. “I almost lost it, and suddenly, I won by a knockout! It was the most beautiful thing that happened in my life.”

After a tune-up stoppage of Ricardo Moreno in Sao Paulo six weeks later, Jofre returned to the Olympic to face Mexican Eloy Sanchez for the National Boxing Association bantamweight title that was shockingly vacated by the 24-year-old Jose Becerra, who stopped Sanchez in his most recent effort. Sanchez proved no match for the brilliant Brazilian, who turned out the Mexican’s lights with a single right cross to the jaw in round six. The blow was so powerful that Sanchez executed a near back flip before hitting the floor, where he remained for several minutes. The decisive victory also earned Ring Magazine’s recognition as world bantamweight champion.

Jofre elevated his standing further by winning his next six fights by knockout, two of which were achieved in title defenses against Piero Rollo and Ramon Arias. But the South American couldn’t claim unquestioned supremacy until he met and beat Johnny Caldwell, a Northern Irishman who outpointed Alphonse Halimi to win the European Boxing Union version of the bantamweight title and repeated the points victory five months later following two non-title wins over Pierre Vetroff (W 10) and Juan Cardenas (KO 8). Like Jofre, Caldwell took part in the 1956 Olympics, and, unlike Jofre, he made the medal stand as he earned a bronze in the flyweight tournament.

The unification fight was made for January 18, 1962 at Sao Paulo’s Gimnasio Estadual do Ibirapuera, with former featherweight champion Willie Pep serving as referee. After Caldwell won the opening session, Jofre seized control for the remainder of the contest. Jofre’s stinging jabs bloodied Caldwell’s nose in the third while a trademark bomb produced a three-count in round five. Jofre continued to batter the gritty Caldwell over the next four rounds and in the 10th, he scored a second knockdown, this time for a nine-count. Caldwell bravely arose but Jofre’s follow-up assault had him reeling so badly that manager Sammy Docherty jumped into the ring to signal surrender. The 20,000 that witnessed the contest set a new South American indoor record, and the $60,000 gate set a new national record.

“Eder Jofre was the greatest bantamweight and the hardest hitter for his weight of all time,” Caldwell said later. “I remember the place was packed to the rafters and there were many thousands locked outside the arena. As it turned out, it was my first defeat as a professional (after 25 straight wins) and it was hard to take.”

Caldwell wasn’t the only bantamweight to feel the pain after fighting Jofre, for over the next three years Jofre ruled the division with his pair of iron fists. He scored knockouts in all five title defenses against Herman Marques (KO 10), Jose Medel (KO 6), Katsutoshi Aoki (KO 3), Johnny Jamito (KO 11) and Bernardo Caraballo (KO 7), which extended his overall KO streak to 17. He achieved this despite his persistent war with the scale, which sometimes extended to fight day. He scaled a half-pound over before the Jamito bout, but, after a half-hour, managed to squeeze down to 117 3/4. This malady often forced Jofre to either gun for the early stoppage or marshal his energy for long stretches before striking, as was the case against Marques, who won the early rounds before yielding to Jofre’s power.

With every victory, the talk of Jofre moving up to featherweight and challenging Vicente Saldivar heated up that much more. But in the end, the Brazilian opted to remain at bantamweight, ostensibly to continue earning a defending champion’s purse. Six months after stopping Caraballo — his first fight in 18 months — Jofre traveled to Japan to meet former flyweight champion Masahiko “Fighting” Harada, a perpetual motion machine who had won 11 of his last 12 fights since losing the flyweight title to the man he dethroned, Pone Kingpetch, in January 1963. The only loss during this stretch was a shocking sixth-round KO to two-time Jofre victim Jose Medel. For this reason, among others, experts expected Jofre to stop Harada, but on the day of the fight Jofre was a narrow 3-to-2 betting choice.

The 29-year-old Jofre stated before the bout that a victory here would be his last because he wanted to spend more time tending to his business interests in Sao Paulo. Another compelling reason was weight-making, which by now was an ordeal.

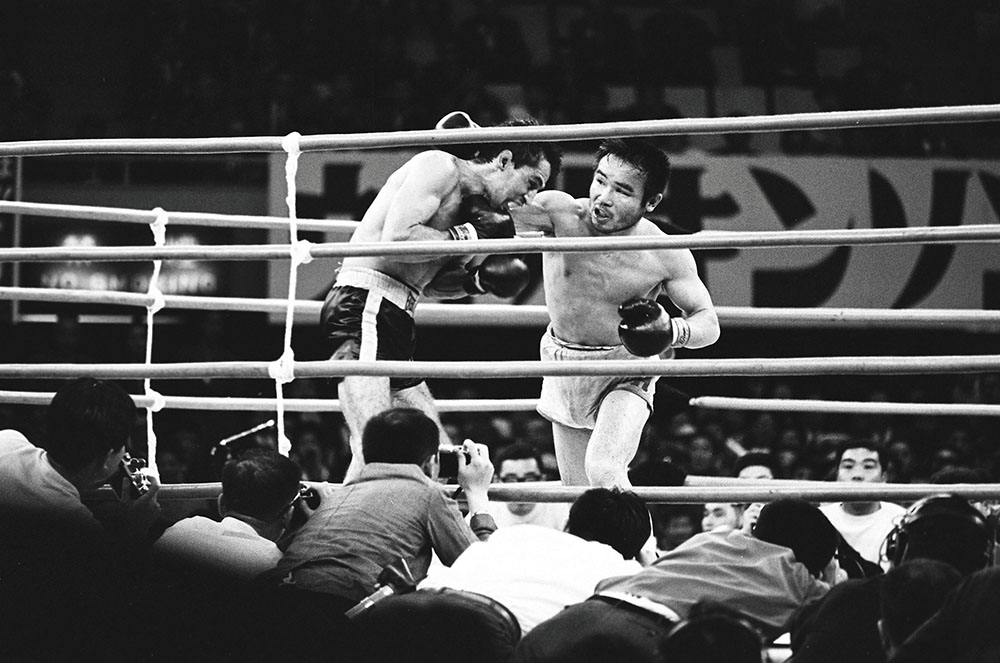

Harada would best Jofre again in their rematch. (Photo by The Asahi Shimbun via Getty Images)

“I had to go for hours without eating,” Jofre told Smith. “I had to train in sweat clothes and plastic covers, jump rope, and endure that unbearable heat under all those clothes, and this was not good. After some time, I found that I was losing water from my body, the necessary water and not the fat.”

According to Dusgate’s story, Jofre scaled more than two pounds over the limit, forcing him to run for an hour in order to make the championship limit, which he did by a quarter-pound.

“I thought to myself, ‘after this fight I’m going to eat and drink until I make heavyweight!’ ” he joked later.

The difference in energy level was profound as Harada bolted from his corner round after round and often met Jofre three-quarters of the way across the ring. Jofre tried — and failed — to match Harada’s overwhelming work rate and the fight’s key moment occurred in round four when a savage counter right uppercut to the jaw shook Jofre to his core. Harada gunned for the knockout, but Jofre’s resilience saw him through to the end. Jofre somehow shook off the punishment and produced his best round in the fifth, but the rally proved short-lived thanks to Harada’s never-ending hustle and offensive variety.

The decision was split; American judge Jay Edson saw Jofre a 72-71 winner under the five-point must system while Japanese jurist Masao Kato saw his countryman a narrow 72-70 victor. The deciding vote was cast by the referee, the legendary Barney Ross, whose 71-69 score for Harada permanently removed Jofre from the undefeated ranks. While Jofre was paid $30,000, Harada purse was just $3,300.

Confronted with the first loss of his 51-fight career, Jofre took a break before deciding to continue his career and pursue a rematch with Harada, who sandwiched a title-retaining decision over Alan Rudkin between a pair of non-title 12-round wins over Katsuo Saito and Soo Kang Suh. Jofre returned five-and-a-half months later in Sao Paulo against 61-fight veteran Manny Elias, and while Jofre swept the scorecards (198-193, 197-195, 196-195 under the rarely-used 20-point must system), he was victimized by a Brazilian rule in which a boxer had to win by at least four points on at least two scorecards in order to be credited with a decision victory. According to Smith, the reason for the rule was to maintain a young fighter’s prestige early in their career by not having them suffer too many losses, to ensure attractive matchups between talented fighters, and to discourage managers from shielding their fighters from tough opponents. While the rule was mainly targeted toward prospects, Jofre, a former champion, had to absorb the sting of a blemish that would have been a victory virtually every other place in the world. That said, Jofre didn’t impress; the Ring’s Hector San Cristobal opined that many in attendance felt the inspired Elias had done enough to upend the Brazilian legend, who weighed 121 1/4 to Elias’ 121 1/2. Jofre himself told Smith that the draw verdict was fair. Still, it was enough to earn Jofre the rematch against Harada.

Any questions about Jofre’s motivation were answered the moment Jofre stepped on the scale, for he weighed a shockingly light 116 pounds while Harada, who had his own weight-making wars, was 118. Jofre also fought much better, especially in the first four rounds when his powerful right hands found the mark time and again. From round five onward, however, Harada’s consistent work rate opened statistical gaps large enough to overcome a round penalty for butting in round seven. Jofre summoned a rally in rounds 10 through 12 but the Brazilian’s momentum was stopped cold in the 14th when another butt opened a massive cut over Jofre’s left eye. This time, the decision in Harada’s favor was unanimous.

Eder Jofre and soccer legend Pele.

The financial rigors of retirement (exacerbated by the side deals made by manager Abraham Katzenelson that made him more money from Jofre’s title fights than Jofre did) and the love shown to Jofre during an extended exhibition tour with a troupe of male and female boxers and wrestlers convinced him that he was still an idol to his people. Jofre returned to the ring in August 1969 following a nearly 39-month layoff against 76-fight journeyman Rudy Corona. Weighing a solid 124 pounds, Jofre scored a sixth round TKO. Between January 1970 and September 1972 Jofre fought 13 times and won them all, seven by knockout. Two victories stood out — a 10-round decision over Manny Elias in May 1970 and a ninth-round KO over Shig Fukuyama in August 1972. Following a third-round knockout over Djiemai Belhadri the following month, Jofre signed to fight WBC featherweight champion Jose Legra, who, at age 30, was seven years younger, four inches taller than the 5-foot-4 Brazilian and who also sported an impressive record of 128-9-4 (49).

Legra, called the “Pocket Cassius Clay” for his Ali-like stick-and-move style and live-wire personality, was making the first defense of the belt he won from an overweight Clemente Sanchez nearly five months earlier. The Spain-based Cuban wasn’t concerned about defending his championship on Jofre’s home turf; after all, he dethroned the Mexican Sanchez in Mexico and, at least on the surface, he enjoyed every conceivable advantage.

Legra’s advantages in youth, speed and footwork were quickly evident as the champion towered over the crouching Jofre and his frequent jabs snaked in with troubling rapidity. Just before the end of round three Legra landed a snappy right to the chin that propelled Jofre backward toward the ropes, where he then fell to all fours. Referee Jay Edson didn’t issue a count because the bell had already sounded, but the knockdown — only the second of Jofre’s career — crystallized the challenge that was before him.

With his head still buzzing from the knockdown, Jofre produced his best round of the contest in round four. Right after right struck Legra’s jaw and every connect produced roars of delight from the sellout crowd in Brasilia. Stunned by Jofre’s rally, Legra used his legs to maintain a healthy distance from the challenger for the rest of the contest, which went the full 15 rounds.

The contest’s shifting tides were represented by the widely divergent scores. Lorenzo Sanchez awarded 143 points to both fighters but he was overruled by Newton Campos and referee Edson, both of whom scored 148-143 and 146-141 for the winner — and new champion.

The overjoyed Jofre was lifted onto the shoulders of those who poured into the ring. Nearly eight years after losing his bantamweight title to Harada, Jofre was a world champion again. Not only was he the oldest man ever to win a widely recognized share of the featherweight title, he was only the fourth man to achieve the bantamweight-featherweight double (George Dixon, Terry McGovern and Harry Jeffra preceded him).

After scoring non-title victories over Godfrey Stevens (KO 4) and Frankie Crawford (W 10), the long-awaited “dream match” between Jofre and Vicente Saldivar was made. Three years earlier Saldivar had pulled off his own incredible comeback by dethroning Johnny Famechon in just his second fight in two-and-a-half years, but, for him, it was not to be. The 30-year-old Saldivar, who had not fought since out-pointing Crawford 27 months earlier, no longer had the magic while the rejuvenated Jofre, five months short of his 38th birthday, was in perfect working order. A blow to the solar plexus followed by a beautifully delivered left to the chin took out Saldivar in round four. Saldivar never fought again and Jofre’s ailing father/trainer would never again see his son compete in the prize ring. On March 24, 1974 Aristides Jofre died of lung cancer.

The WBC ordered Jofre to defend his title against mandatory challenger Alfredo Marcano, but excessive squabbling between Jofre’s co-managers Katzenelson and Marcos Lazaro hindered efforts to make the fight. Lazaro flew to the WBC’s headquarters in Caracas and apparently struck a deal, but because Katzenelson objected to the terms Jofre was stripped of the title on June 17, 1974. Though Jofre would notch seven more victories before retiring in October 1976 at age 40, he never again engaged in a world title contest.

Upon retirement, Jofre’s battleground shifted to the political arena, spending several years as an alderman in Sao Paulo.

More than four decades after his final fight, Jofre’s brilliance remains beyond dispute. The Ring ranked him 85th in its list of boxing’s 100 greatest punchers and 19th in its list of the “80 best fighters of the last 80 years” in 2002. He was elected to the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1992 (where he boxed an exhibition against fellow legend Alexis Arguello) as well as the World Boxing Hall of Fame and the West Coast Boxing Hall of Fame. Historian Herb Goldman rated Jofre the top bantamweight in history, as did the International Boxing Research Organization (IBRO). Additionally, IBRO director Dan Cuoco ranked Jofre the second-best pound-for-pound fighter behind Sugar Ray Robinson.

As brilliant as Jofre was inside the ring, his legacy is even more so. That legacy will speak for him for the remainder of time.

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, West Virginia. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 21 writing awards, including two first-place awards, since 2006. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. as well as a panelist on “In This Corner: The Podcast” on FITE.TV. He is the author of “Tales from the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics” (available on Amazon) and the co-author of “Muhammad Ali: By the Numbers” (also available on Amazon). To contact Groves use the email [email protected] or send him a message via Facebook and Twitter (@leegrovesboxing).