Larry Holmes-Gerry Cooney: Fanning the Flames

By Randy Gordon

This feature originally appeared in our Larry Holmes Special Issue which is available for purchase at The Ring Shop.

THE UGLY, RACIALLY CHARGED BUILDUP TO THE 1982 SUPERFIGHT BETWEEN LARRY HOLMES AND GERRY COONEY WAS AN UNFORTUNATE THROWBACK TO “GREAT WHITE HOPE” PROMOTIONS OF THE PAST

It was a typical broiling summer day in Nevada as the referee brought the fighters together at mid-ring to start their long-anticipated heavyweight championship fight, which the promoter billed as “The Fight of the Century.” It was the ultra-popular undefeated white challenger, who was called “The Great White Hope,” against the powerful black champion.

As the two stood face to face in mid-ring, the challenger said to the champion, “Today, White America is going to be proud.” The champion merely flashed a wide smile at the challenger in return. He didn’t have to say anything. His smile said more than words. The challenger knew, then and there, it wasn’t going to be his night. He was right. The champion toyed with him – much to the dismay of White America – stopping him in the 15th round.

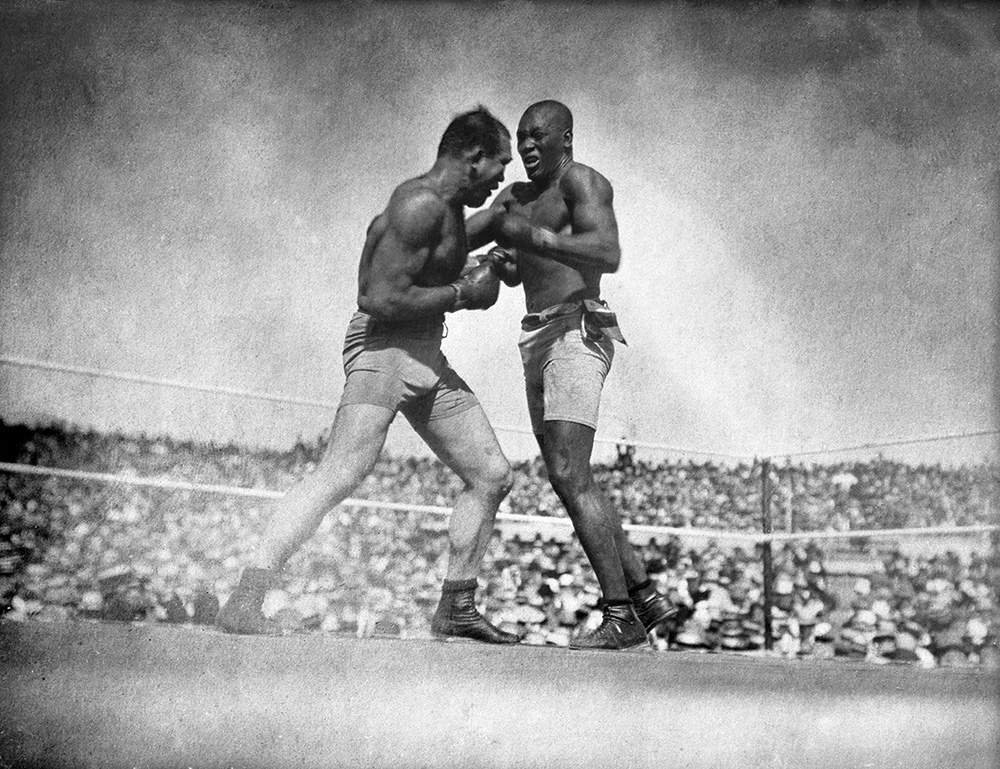

That fight, which matched heavyweight champion Jack Johnson against former heavyweight champion James J. Jeffries, took place on July 4, 1910, in Reno, Nevada. The venue was constructed solely for this purpose – the first time an arena had been constructed for a single event – and put in nearly 16,000 fans – 99 percent of them white. Sadly, the fight was based much more on race than on boxing.

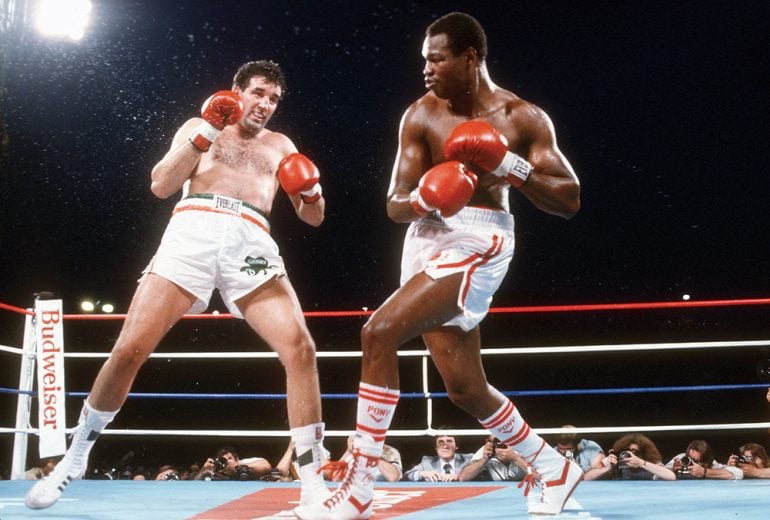

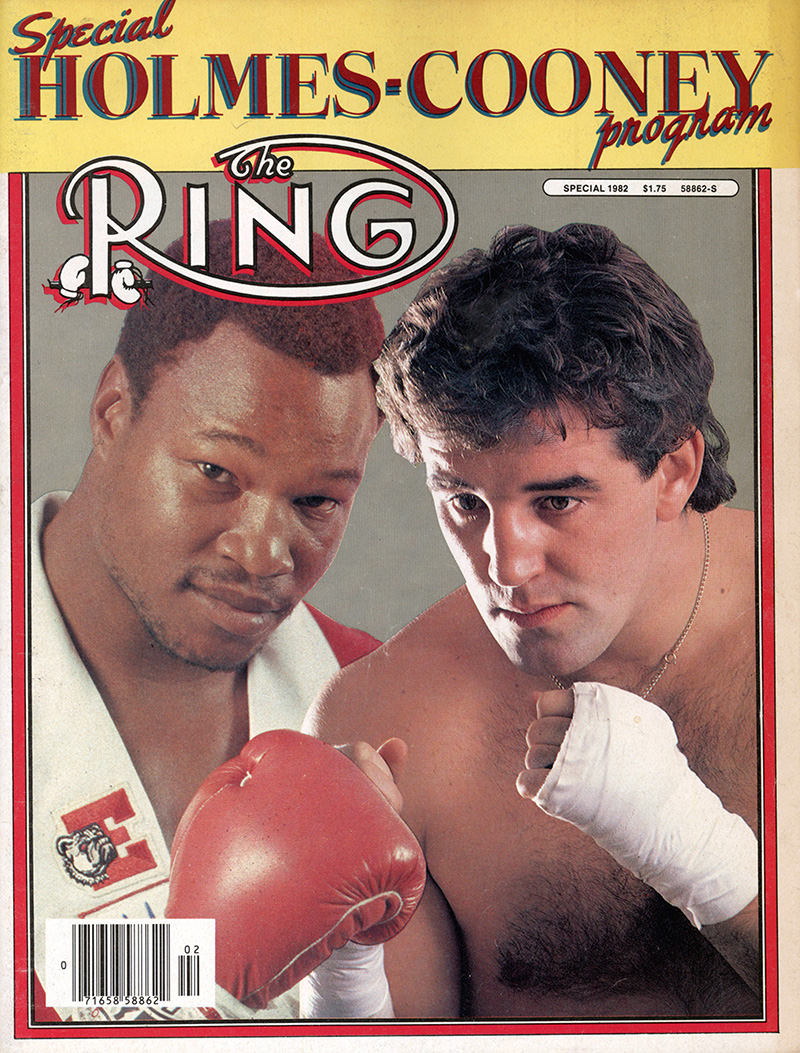

The Holmes-Cooney pre-fight commentary conjured up ugly memories of Johnson-Jeffries. (Photo by PA Images via Getty Images)

It was originally supposed to take place in San Francisco, but three weeks before the bout, California Governor James Gillett made promoter Tex Rickard take it out of the state due to pressure from church groups and civic leaders on grounds that the fight was morally and religiously wrong. Rickard bailed out and quickly moved the bout to Reno, where boxing between men of any color was legal.

Jeffries had retired almost six years earlier, after a sixth-round knockout of Jack Munroe. The title then bounced from Marvin Hart in 1905 to Tommy Burns in 1906. But when Johnson took the title from Burns in 1908, toying with him on the way to police stopping the fight in the 14th round of their scheduled 20-rounder, White America began the search for a “Great White Hope.” It desperately wanted someone to beat the brash, arrogant, rule-defying Johnson.

The champion toyed with him – much to the dismay of White America – stopping him in the 15th round.

All it could come up with was the 35-year-old, sadly out-of-shape Jeffries. The talk of “saving America” – along with $101,000 (almost $3 million today) – was enough to make Jeffries end retirement.

As he had done with so many opponents, the 208-pound Johnson played with the 227-pound “Boilermaker” from Burbank, California. Johnson ended the fight in the 15th round with three knockdowns.

Following the fight, race riots broke out across the country, with black men being attacked by angry white mobs. “The Great White Hope” had been battered, bloodied and beaten, and White America wouldn’t stand for it.

White America finally got what it was looking for on April 5, 1915, when Jess Willard fulfilled their “hopes,” beating Johnson by knockout in the 26th round.

***

Following Willard’s victory, White America lost its “need” for a “Great White Hope.” That’s because the next heavyweight champion of African-American descent came along 22 years later in the form of Joe Louis, who was a beloved figure both in and out of the sport.

Following Louis were two African-American heavyweights – Ezzard Charles and Jersey Joe Walcott. Neither was flamboyant enough to antagonize White America. They were respected by everyone. When Rocky Marciano stepped into the ring in September 1952 to face Walcott, he was not regarded as a “Great White Hope.” He was just “The Brockton Blockbuster.”

Following Marciano were Floyd Patterson and Sonny Liston, with a quick visit to the heavyweight title by Ingemar Johansson.

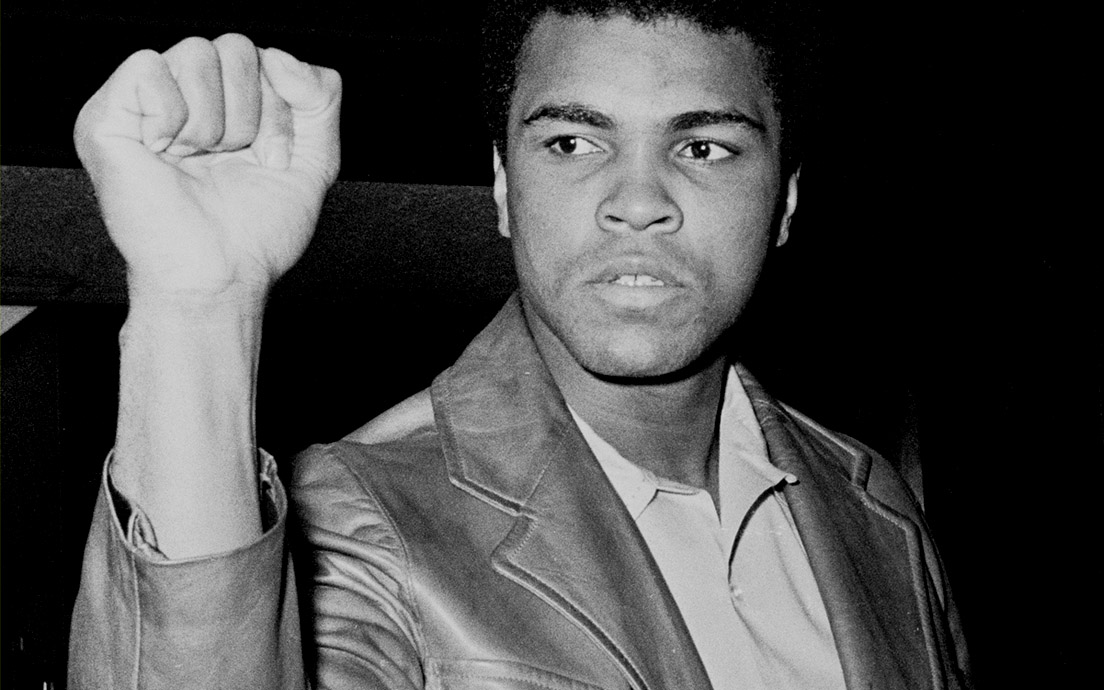

The rise of Muhammad Ali triggered White America once again.

While Sonny Liston was no fan favorite, the man who took his title – Cassius Marcellus Clay – was brash, loud and controversial, just like Jack Johnson. Outside of die-hard boxing fans, much of White America wanted to see Clay – who became Muhammad Ali in 1964 – beaten. The term “Great White Hope” was pulled out of mothballs.

At one point, Henry Cooper, Karl Mildenberger, Brian London, George Chuvalo, Joe Bugner, Oscar Bonavena and Richard Dunn were all regarded as “White Hopes.”

In the mid-1970s, along came the Bobick Brothers – Duane and Rodney. Both were touted – much to their chagrin – as “White Hopes,” especially Duane. A 58-second knockout loss to Ken Norton on May 11, 1977, ended his title aspirations, and back-to-back stoppage losses two years later ended his career.

***

At the time Bobick’s title dreams were ending, Gerry Cooney’s were just beginning. He was the new breed of heavyweight – 220-plus pounds and just over 6-foot-6. He was also a brutal puncher, with a left hook unmatched by any heavyweight on the planet.

Cooney turned pro in 1977, winning all seven of his fights that year, six by knockout. He followed with eight more fights, eight more victories and six more knockouts in 1978. He was the fastest-rising, most talked-about heavyweight in the world.

“I can’t stand the ‘Candy Kisses Cooney’ nickname, and I feel just as strongly about ‘The Great White Hope.’”

– Gerry Cooney

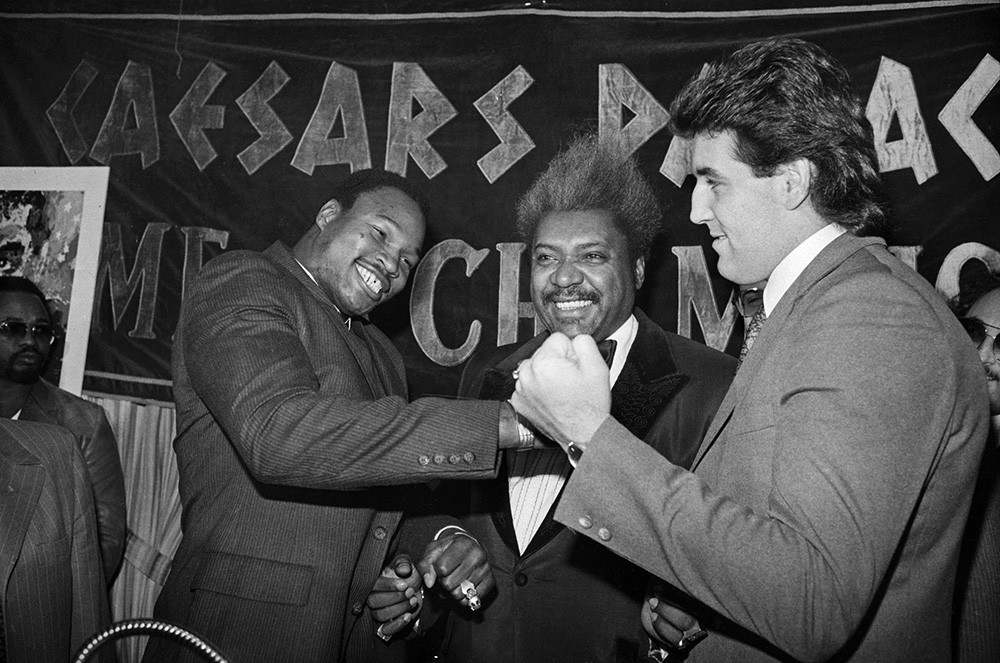

When Larry Holmes beat Ken Norton for the WBC title on June 9, 1978, Cooney was 11-0 and heading up the ratings. Promoter Don King, who had promotional rights with Holmes, also wanted to sign Cooney.

Cooney’s management team of Dennis Rappaport and Mike Jones wanted Cooney to stay a free agent. They kept him busy. Cooney fought four times in 1978 after Holmes beat Norton, and seven more times in 1979. Included was a third-round stoppage of contender John Denis in Madison Square Garden on November 9 of that year. The victory over Denis upped Cooney’s record to 21-0. Every victory took him another step closer to a shot against Holmes. It also made him the newest in boxing’s long line of “Great White Hopes.”

Cooney didn’t like the label any more than he liked the nickname his managers had suggested for him when he turned pro: “Candy Kisses Cooney.”

“I’m neither of those names,” Cooney said back then. “I can’t stand the ‘Candy Kisses Cooney’ nickname, and I feel just as strongly about ‘The Great White Hope.’”

“Candy Kisses Cooney” disappeared. “The Great White Hope” label didn’t, especially after back-to-back first-round knockouts of Ron Lyle in October 1980 and Ken Norton in 1981. Ironically, the destruction of Norton came on the same date (May 11) and arena (MSG) as Norton’s first-round wipeout of Duane Bobick four years earlier.

After Cooney’s 54-second annihilation of Norton, Holmes-Cooney was inevitable.

***

Following Cooney’s win over Norton, which upped his record to 25-0 (21 KOs), Larry Holmes told The Ring, “Me and Cooney is gonna happen. I can’t wait until that day, because I don’t like him. I don’t like ‘Looney Cooney’ one little bit.”

Holmes stayed busy in 1981, fighting Trevor Berbick one month before Cooney faced Norton. Holmes then fought twice more that year – against Leon Spinks in June and Renaldo Snipes in November – which upped Holmes’ record to 39-0 (29 KOs). A fight against Cooney was signed right after the Snipes fight. It was set for March 25, 1982.

Artist LeRoy Neiman, a huge boxing fan, painted the poster for Holmes-Cooney. Both the poster and the fight had to be put on hold when Cooney suffered a shoulder injury. The shoulder needed rest and rehab, not surgery. The bout was rescheduled for June 11.

A brief moment of levity during an otherwise poisonous buildup.

From the moment the fight was announced, a bitterness not seen in boxing since Johnson vs. Jeffries emerged.

The promotion should have been about the two best heavyweights on the planet battling it out for the heavyweight championship. The promotion should have been about one of the best heavyweight champions ever against a solid contender. The promotion should have been about Larry Holmes’ great jab against the rib-cracking power of Cooney’s left hook.

Instead, the promotion became about race. It was black vs. white. It was the black champion against the “Great White Hope.”

Cooney wasn’t into it but his managers – who believed the racial polarization would sell the fight more – were.

“Cooney is not the ‘White Hope,’” said his co-manager, Mike Jones. “He is the ‘Right Hope.’”

At a press conference for the fight, Don King said, “This is not about black against white. It is not about race in any way. It’s boxing’s two biggest, best heavyweights. One happens to be black. One happens to be white.” For a fight not about race, both sides were doing a terrific job about reminding everyone that it was black against white.

The bitterness between the two fighters built.

One day, while at a fight card being televised by ABC, Cooney was asked to join sportscaster Howard Cosell at ringside. During Cosell’s interview, Holmes walked to within a few feet from where Cosell stood with Cooney. Words were tossed back and forth. Cooney reached out to slap Larry. Security had to step in to separate them. It was that way every time they ran into each other.

“I was 11 years old when Jack Johnson fought James J. Jeffries,” Hall of Fame trainer Ray Arcel told The Ring the week before the fight. Arcel was one of Holmes’ cornermen for the Cooney fight.

“Johnson-Jeffries was disgustingly racial,” said Arcel. “This fight is worse.”

***

The 10-fight undercard was interesting and was fought in temperatures that exceeded 100 degrees. Featured were three heavyweight bouts and a junior featherweight championship in which Wilfredo Gomez, of Puerto Rico, stopped rugged Mexican challenger Juan Antonio Lopez in the 10th round.

In those heavyweight bouts, James “Quick” Tillis picked himself off the canvas in the ninth round to hold on and win a 10-round unanimous decision over hard-hitting Earnie Shavers; Trevor Berbick won a 10-round unanimous decision against Greg Page, handing him his first defeat in 20 fights; and Mitch “Blood” Green won a six-round unanimous decision against Walter Santemore. Green had been Holmes’ main sparring partner for the fight, with his height (nearly 6-foot-6) and long reach helping Holmes prepare for Cooney.

Finally, it was fight time. Around us was an awesome, breathtaking scene. There was a capacity crowd of 29,284 (with a paid gate of $7,293,600). Behind me and The Ring’s publisher, Bert Sugar, was the “celebrity section.” It was star-studded: Jack Nicholson, Wayne Gretzky, Farrah Fawcett, Ryan O’Neal and Joe DiMaggio were just a handful of the rich and famous who had come to witness this event.

A roar went up. One of the fighters was on his way to the ring. It was Gerry Cooney. A few moments later, Holmes made his way into the ring to an equal ovation. Then something very curious happened.

Ring announcer Chuck Hull took the microphone as the timekeeper rang the bell. Hull began his introductions. Instead of announcing the challenger first, followed by the champion, it was the other way around.

“Introducing, in the red corner, fighting from Easton, Pennsylvania, weighing 212½ pounds, the undefeated WBC heavyweight champion of the world, the ‘Easton Assassin,’ Larry Holmes.”

Did Chuck Hull actually introduce the champion first? Sugar was so stunned that his jaw dropped and his unlit cigar fell onto the press table.

“What the …,” uttered Sugar.

Hull continued.

“And, in the blue corner, fighting out of Huntington, New York, weighing 225½ pounds, he is undefeated in his professional career, he is ranked number one by both the WBA and the WBC … introducing ‘Gentleman’ Gerry Cooney.”

Why was Holmes introduced first? The champion is always introduced after the challenger.

“I was asked on my way out of the dressing room if I’d mind being introduced first. I really didn’t care,” Holmes told The Ring. “I really didn’t. That was Gerry’s night. I got that. He could have anything he wanted – except the victory.”

Referee Mills Lane met with both fighters in the middle of the ring. He quickly went over the instructions he had given both in detail in their respective dressing rooms. He asked if either “have any questions.” Then he said, “Shake hands and let’s get it on!”

As the two touched gloves, Holmes said, “Let’s have a good fight!”

Those five little words set the tone of what would become a heavyweight classic. Those five little words were five of the most meaningful words Larry Holmes ever spoke. Those five little words were five of the most powerful Gerry Cooney ever heard. To him, those five words meant, “Forget all that racial stuff. Forget the animosity. Forget the name-calling. Forget the ugliness. We’re fighters, and this is what we do. Let’s have a good fight!”

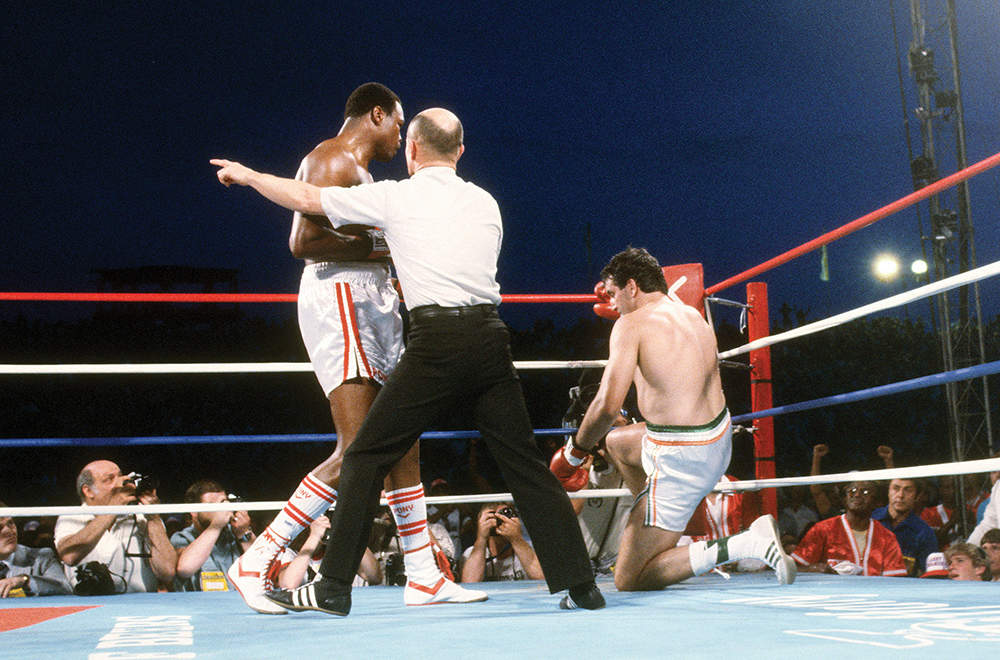

It was Holmes’ speed and class vs. Cooney’s explosive hitting power. (Photo by Focus on Sport/Getty Images)

As the fight was about to start, I reached into my left jacket pocket for my bottle of water. It was stuck. It was quite obvious as I pulled and tugged to get it out.

“What are you doing?” asked Sugar.

“I’m trying to get my water,” I replied.

He then leaned close and said, “Listen, I heard from my friend in the FBI that there are sharpshooters all over the arena.”

“What!” I gasped.

“Look on top of Caesars Palace,” he said.

I turned to my right and looked up. On the roof of Caesars Palace, off in the distance, I saw a few tiny figures. Riflemen. Sharpshooters. They were looking through telescopic sights on high-powered rifles.

“They are in the camera stands, too,” said Sugar. “They’re hidden behind the plastic drapes. Death threats were made to both Holmes and Cooney. The FBI is watching everyone in this crowd. So, keep your hands out of your jacket pocket.”

As thirsty as I was, I didn’t reach for my water bottle again.

***

In Round 1, Holmes boxed and moved in circles, firing quick, long jabs as Cooney stalked him, trying to time his rhythm.

Round 2 was interesting, with Holmes boxing and showing his world-class jab as Cooney continually pressed him, looking to land his vaunted hook.

With 30 seconds remaining in the round, Cooney was caught with a right to the head. He wobbled, stumbled and fell.

“I thought to myself, ‘What are you doing down here, Gerry?’” Cooney said to The Ring. “‘Get up and fight.’” He did exactly that, winning many of the next few rounds with his pressure and surprisingly quick hands.

A sharp right cross put the challenger down late in Round 2. (Photo by Focus on Sport/Getty Images)

The rounds melted away in the Las Vegas heat, which exceeded 120 degrees in the ring. After six rounds, judge Duane Ford had Cooney ahead, 57-56, while judges Dave Moretti and Jerry Roth had Holmes by 57-56 and 58-55, respectively.

In the ninth, as Cooney was aiming a left uppercut to the body, Holmes fired a left that sailed over Cooney’s right shoulder. As Cooney was bending to his left to deliver the punch, Holmes’ left wrapped around Cooney’s neck, pulling him down. The uppercut landed with a resounding thud – directly between Holmes’ legs. The crowd let out a collective “Ohhhhhh!” Holmes doubled over in agony. Cooney stood by, watching as referee Lane went over to Holmes to ask if he was OK. When he said he needed a few moments, Lane turned to Cooney and deducted two points from him for the low blow.

“I was horrified,” said Cooney. “I didn’t mean that.”

Holmes walks in pain after the low blow from Cooney.

While all three judges had Cooney winning the round, all marked their scorecards 9-8 for Holmes because of the deduction. Holmes recovered quickly, and the fight resumed.

Holmes and Cooney split the next two rounds, with Cooney having his best round in the 10th. In the closely contested 11th, Cooney lost another point for a low blow and lost the round 10-8 on all three judges’ scorecards.

The greatness of the champion, combined with the brutal heat and Cooney’s inactivity coming into the fight, started to catch up with Cooney in the 12th. His punches became slower and his punch volume dropped.

“I saw that,” Holmes told The Ring, “so I picked up the pace.”

In the 13th round, Holmes’ experience and recent activity – and Cooney’s lack of it – brought the fight to a conclusion.

The champion used his jab – perhaps the best in heavyweight history – over and over. Cooney couldn’t stop it. With 30 seconds remaining in the round, Holmes let his hands go. He stepped inside and unleashed a volley of blows. A right uppercut to the chin staggered Gerry. With just over 10 seconds to go in the round, a sharp right to the head turned Cooney’s legs to spaghetti and he wobbled, sagging against the ropes. Had his right arm not been draped over the top rope, Cooney would have gone down.

Victor Valle had seen enough. He wasn’t just Gerry’s trainer. Gerry was like a son to him. Valle sprang through the ropes and headed to his fighter. Referee Lane immediately waved the fight off as Valle hugged his beaten fighter. Under Nevada rules, the fight was a disqualification at 2:52 of the 13th round because of Valle entering the ring, however the official outcome was a TKO for Holmes. (The night of the fight, NSAC Executive Director Harold Buck considered changing the result to a DQ, but it never happened. Holmes told me, “I don’t care how they ruled it, as long as they put a ‘W’ in front of the result!”)

There was minor post-fight controversy as judges Ford and Moretti each had Cooney winning in rounds, 7-5, but trailing on points, 113-111. Had Cooney not been penalized three points, they would have had him in the lead at the time of the stoppage.

In a recent interview with The Ring, Cooney said, “The scorecards didn’t matter. I still had two more rounds to go with that great champion. I learned so much from that fight. Holmes taught me so much. I was always hoping for a rematch, but it just didn’t happen.”

In his post-fight interview, Holmes said, “They keep saying that I’m not what Muhammad Ali used to be, or Joe Louis or Joe Frazier or George Foreman. I don’t want to be what those guys used to be. I just want to be Larry Holmes. I just want to fight for the people. No colors involved, nothing like that.”

Immediately after the fight, Cooney was choked up, apologizing to those who had rooted for him, continually saying, “I’m sorry.” He said he’d be back to work in the gym soon and return to action before long. He didn’t anticipate the deep hole of alcoholism he was about to fall into and the 27 months of inactivity that would follow.

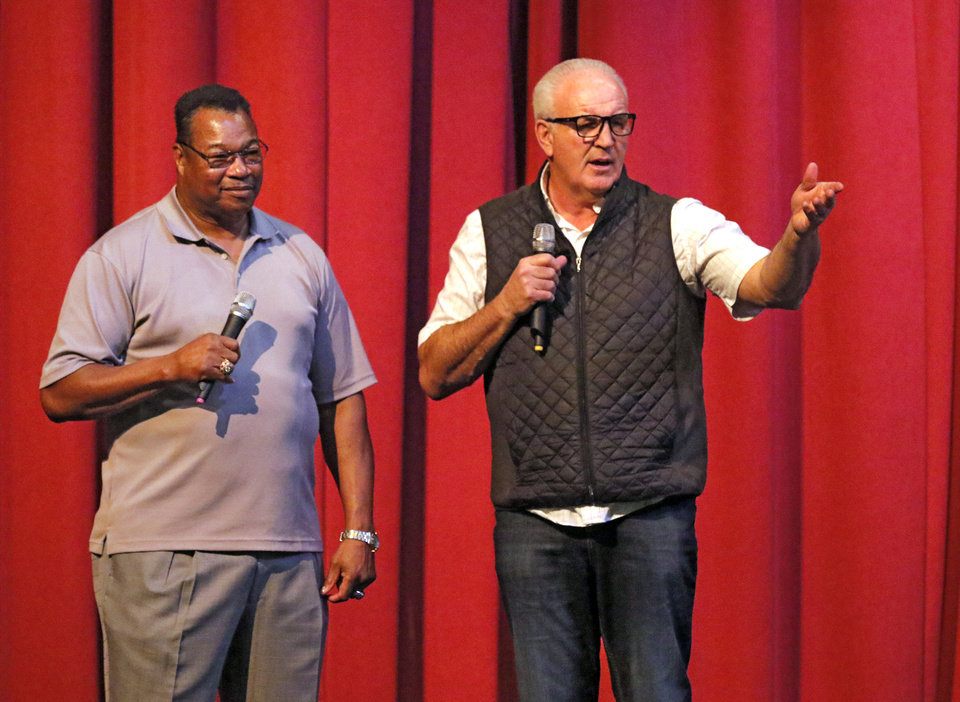

(Photo by Steve Gooch/The Oklahoman)

Holmes made a phone call to Cooney almost two years after the fight, telling him, “You are a hell of a fighter. It’s time for you to get back into the ring.” Those words reignited Cooney’s drive to fight again.

Holmes finished his Hall of Fame career in July 2002, after a 10-round decision win against Eric “Butterbean” Esch. He was 69-6 (44 KOs). Cooney finished his after a second-round stoppage loss to George Foreman in January 1990. His final numbers were 28-3 (24 KOs).

Now, as the 40th anniversary of the fight approaches, Larry Holmes and Gerry Cooney have become best friends. They attend functions together, they visit each other’s home and they travel together.

Yes, it’s been 40 years since Larry Holmes faced Gerry Cooney in a great fight with an ugly, racially charged buildup. It has been 40 years that have seen them go from being bitter enemies to inseparable pals.

With the anniversary of the Larry Holmes-Gerry Cooney fight at hand, we think back to that unforgettable fight in the Nevada desert 40 years ago.

Although the pre-fight atmosphere felt the same as that other heavyweight title fight in the desert 112 years ago must have felt, nothing but good has come out of Holmes-Cooney.

I think all who were there or watched it and rooted for one guy or the other have learned a lot, and maybe even changed for the better.

It’s a long way we’ve come from those nights in the Nevada desert, both in 1910 and in 1982.

SUBSCRIBE NOW (CLICK HERE - JUST $1.99 PER MONTH) TO READ THE LATEST ISSUE