Archie Moore-Yvon Durelle 1: An epic comeback from The Old Mongoose

He was billed as the “Fighting Fisherman,” and in the biggest fight of his life Yvon Durelle seemed to be on the verge of reeling in a 173¾-pound whopper. Light heavyweight champion Archie Moore, a 3½-1 favorite according to the oddsmakers, had been hooked and then dropped early in the first round by a jolting right cross in his Dec. 10, 1958, title bout in the Montreal Forum, and he remained on the canvas, clearly dazed, as referee Jack Sharkey’s count reached eight and then nine.

But the “Old Mongoose,” allegedly 41 at the time but perhaps several years older, arose just before Sharkey’s toll reached 10, much to the consternation of a bundled-up, very vociferous pro-Durelle crowd of 8,484 in the chilly home arena of hockey’s Montreal Canadiens. Durelle partisans so desperately wanted their French-Canadian countryman to claim the 175-pound title that some grumbled that Sharkey, a former heavyweight champion, had perhaps been half-a-tick slow in his count.

“(Moore) was defending his title and I didn’t want to stop the fight because of one knockdown,” Sharkey said of the split second separating what would have been a major upset from an epic comeback by an already legendary fighter that has come to be regarded by many as his most memorable signature victory. “I never met the man and certainly had no reason to favor him. But although he was knocked down a couple more times, he got up, snapped out of it and came back to knock out Durelle.”

As described by Moore, the “snapping out of it” head-clearing that enabled him to survive one of the shakiest stretches of his remarkable career took more time than he might have preferred. He was knocked down twice more in the first round and, even though Sharkey ruled the second a push, hardly anyone else, including Moore, agreed with that assessment. Even now, 63 years later, all the post-fight accounts of the bout indicate the champion had been legitimately floored three times in Round 1, and Archie agreed that indeed was the case.

“He caught me clean every time,” Moore, who went on to knock out Durelle in the 11th round, said of a fight that was fraught with historical significance. “That first-round punch that knocked me down for the first time was a short right, sort of a sneaky right, but I knew that if I kept circling him I’d be all right until I came out of it. It worked out OK, but Durelle sure gave me a rugged time of it in the first four rounds.

“I knew I had him after the fourth round, but before that I was awfully rocky. Durelle is one of the very top light heavyweights I have ever fought. The only stronger fighter I know is Rocky Marciano.”

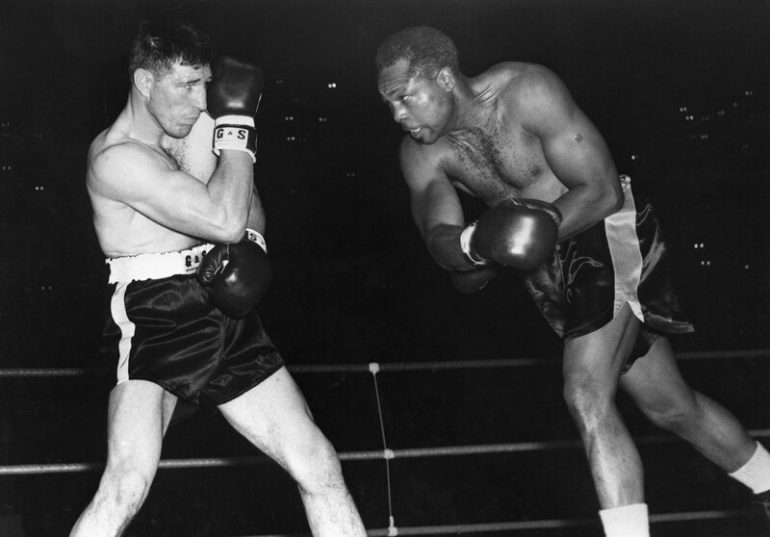

Moore decks Marciano. Photo by The Ring Magazine via Getty Images

The reference to Marciano is noteworthy because, in his first failed bid to win the heavyweight championship he wanted more than anything, Moore – who floored Rocky in the second round — was knocked down five times thereafter in losing by ninth-round KO on Sept. 21, 1955. A massive turnout of 61,574 was on hand for what proved to be Marciano’s final ring appearance.

Husky, uncommonly powerful and woefully lacking finesse, Durelle somewhat mirrored the great Marciano, but he paled in comparison to his stylistic superior. Coming into his first confrontation with Moore (he also would lose the Aug. 12, 1959 rematch on a third-round knockout) he had been defeated inside the distance six times in posting a 79-18-2 (40 KOs) record to that point. His only chance of shocking the world was to get the Mongoose out of there early, and he came ever so close to doing just that. But the moment passed and his window of opportunity eventually began to close, beginning with the fourth round in which Moore, the fog in his brain lifting, began to assert himself with stinging combinations. It never really opened as much as Durelle needed it to even after he dropped Moore again in the fifth round. Once again Moore raised himself up and it soon became apparent that the fish that the Fighting Fisherman had on the line earlier was now the monster destined to get away … forever, as it turned out.

So obvious was the gathering force of Moore’s resurgence that he led on all three official scorecards at the time he finally put away the fading Durelle, by margins of 44-42 (according to judges Leon Germain and Harry Shulman) and 46-45 (Rene Ouimet) on the five-point-must system.

Why did this bout, of all the ones Moore had been involved in during his slow rise up through the so-called “Chittlin Circuit” and even during his championship reign, bear the imprimatur of special circumstance? For one thing, it was the first national telecast in the United States of a world championship bout staged in a foreign country. For another, Moore was looking to break a tie with Young Stribling for the most career knockouts as a professional. A win inside the distance by Moore, who came in with a 175-21-9 record, would be his 127th, giving him sole possession of the top spot.

“I wanted to break the record against a name fighter,” said Moore, who figured that Durelle, then rated No. 3 among light heavyweight contenders behind Tony Anthony and Harold Johnson, qualified. “I didn’t want to do it in some little town against a small-time fighter.”

And once the knockout record was his and his alone?

“This is the happiest I’ve ever been,” Moore proclaimed, maybe because the celebration he had anticipated and finally got to enjoy seemed so iffy at the outset.

“One thing I got awful sick of in there was looking at Sharkey,” he said. “Every time I saw him he was standing over me counting. I had to talk to myself, saying, `Hey, old man, this can’t be age catching up to you. You just can’t let this happen, with the all-time knockout record to be won.’”

For his part, Durelle was crestfallen. The 29-year-old, who was 77 when he passed away on Jan. 6, 2007, sobbed in his dressing room about the golden opportunity that he had failed to capitalize on, and likely would forever replay in his mind without the favorable outcome he so desperately wanted for himself and his home region.

“I think I have let down the people of the Maritimes,” he said. “Now I’m going home to fish and I have no other bouts planned.

“I gave him too many openings. I stood back too much. He covered up too much for me in the first round after the three knockdowns and I couldn’t put across the finishing punch. I was trying too hard. I was too eager.”

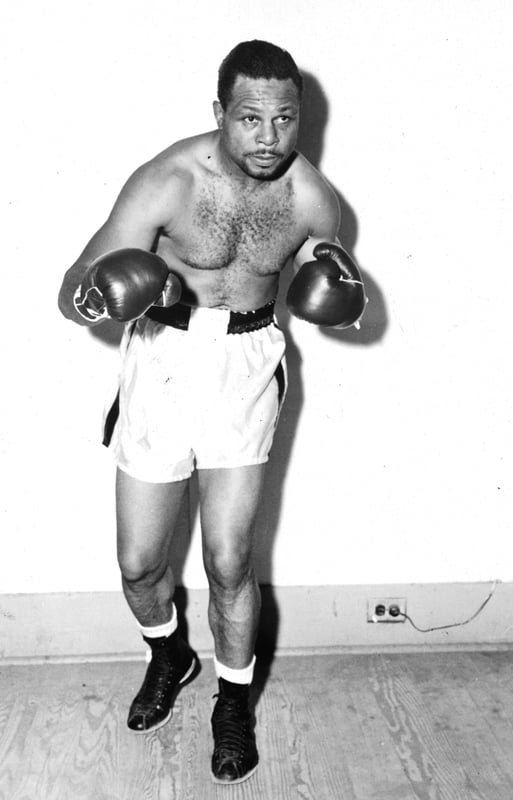

Photo by The Ring Magazine/ Getty Images

There have been boxing matches of greater consequence than Moore-Durelle I. There have been some that were as action-packed and had the same sort of seismic momentum shifts. But for those who were there, and particularly those who have placed Archie Moore on a deserved pedestal reserved for all-time greats, that frigid night when it was nearly as cold in the Forum as it was outdoors shall forever hold a place of honor. Art Rust Jr., the sports historian, author and newspaper columnist who is considered by many to be the godfather of sports talk radio, was 82 when he passed away on Jan. 12, 2010, and to his dying day he maintained that Moore-Durelle I was the greatest fight he had ever seen.

Although the Boxing Writers Association of America did present Moore with its Edward J. Neil Award (now the Sugar Ray Robinson Award) as Fighter of the Year for 1958, The Ring recognized newly crowned heavyweight champion Ingemar Johansson for that same honor, and it cited Sugar Ray Robinson-Carmen Basilio II as its Fight of the Year. Any best-of compilations are, of course, subjective, but one such listing placed Moore-Durelle I as the 18th greatest fight of all time.

It could be that Moore-Durelle I stands at least somewhat apart from a host of similar slugfests because of the legend of the Old Mongoose, arguably the most charismatic and quotable fighter outside of Muhammad Ali ever to lace up a pair of padded gloves. Another light heavyweight champion, Jose Torres, upon the occasion of Moore’s death on Dec. 9, 1998, remarked that “In my view he was the greatest light heavyweight in the history of boxing and one of the greatest boxers in any division. What he accomplished after he was 30 years of age was unbelievable. He became greater and greater as he got older.”

Exactly how old Moore was is even a matter of some conjecture. Archibald Lee Wright – that was his birth name – insisted he came into the world on Dec. 13, 1916, in Collinsville, Ill.; his mother, Lorena Wright, said it was actually Dec. 13, 1913, in Benoit, Miss., an assertion which she said she could back up with a birth certificate.

Moore, on the apparent discrepancy in the two listings of his age, said, “I have given this a lot of thought and have decided I must have been three years old when I was born.”

Over the course of a 27-year professional career that spanned four decades, Moore became as quixotic a figure outside of the ring as he did inside the ropes. He claimed he had a secret weight-reducing formula obtained from Australian aborigines when he boxed there in 1940, which involved the distilled bark of eucalyptus trees. Always conscious of his appearance, he sometimes showed up even for weigh-ins dressed to the nines in a tuxedo and black homburg while jauntily carrying a silver-tipped walking stick.

Today, as skilled, witty and flamboyant a fighter as Moore would have rocketed to widespread popularity much faster than he eventually did, but the era in which he came up was vastly different. He was periodically stalled by his refusal to take an occasional dive or to allow himself to be exploited during a time of blatant racial inequality. He thus had to fight frequently, often for short money, to support his family (which eventually would include eight children) and along the way he had to overcome any number of ailments – acute appendicitis, organic heart disorder, a severed tendon in his wrist, a perforated ulcer that necessitated surgery – that would have slowed down or even driven out a lesser man.

Photo by The Ring Magazine/ Getty Images

It took 17 years for Moore to finally wangle a title shot, against Joey Maxim on Dec. 17, 1952, in St. Louis. He scored a 15-round decision on points, after which a conga line of promoters, managers and assorted hangers-on took their cuts of his purse, leaving the new champ with all of $800. Not only that, but as a condition for receiving his crack at Maxim, Archie had to contractually agree to take on Doc Kearns, who managed Maxim and, before him, Jack Dempsey, to become his manager, the eighth of his career.

Kearns then put Moore on an insanely busy schedule with 43 fights over the next six years. Archie won all but two of those with 25 knockout victories, his only two losses coming in bids for the heavyweight championship, against Marciano and, on Nov. 30, 1956, in Chicago, against 21-year-old Floyd Patterson for the title vacated by Marciano. He lost that time on a fifth-round stoppage.

Was Archie Moore the greatest light heavyweight of all time? Torres thought so, but his opinion is not universally shared. The fact is that Moore was 0-3 against Ezzard Charles, and where he rates in a distinguished group that includes the likes of Billy Conn, Gene Tunney, Tommy Loughran, Charley Burley, Sam Langford, Bob Foster, Michael Spinks and Roy Jones Jr. is always going to be a matter of personal preference. For what it’s worth, in a 2003 listing of the 100 greatest punchers of all time, regardless of weight class, The Ring had Moore at No. 4, behind only Joe Louis, Langford and Jimmy Wilde and ahead of such renowned blasters as Jack Dempsey (7), George Foreman (9), Earnie Shavers (10), Marciano (14), Sonny Liston (15) and Mike Tyson (16).

But it is undisputable that Moore is and shall forever be the fighter most linked to December. Not only did he come into and leave this world in the final calendar month of the year, but he won his title from Maxim during that charmed 31-day period, and retained it on the barnburner over the scrappy Durelle. All in all, Moore was 11-1-1 with 10 KOs in December bouts, the only loss to Harold Johnson snapping a 25-bout winning streak.

Moore’s record of 132 KO victories, given the landscape of today’s boxing, is almost certainly a mark that will never be approached, much less exceeded, and he continues to have the distinction of being the longest-reigning light heavyweight champion, holding the title for nine years and 52 days.

SUBSCRIBE NOW (CLICK HERE - JUST $1.99 PER MONTH) TO READ THE LATEST ISSUE