Ray Mercer TKO 5 Tommy Morrison story doesn’t begin to tell the whole story of either

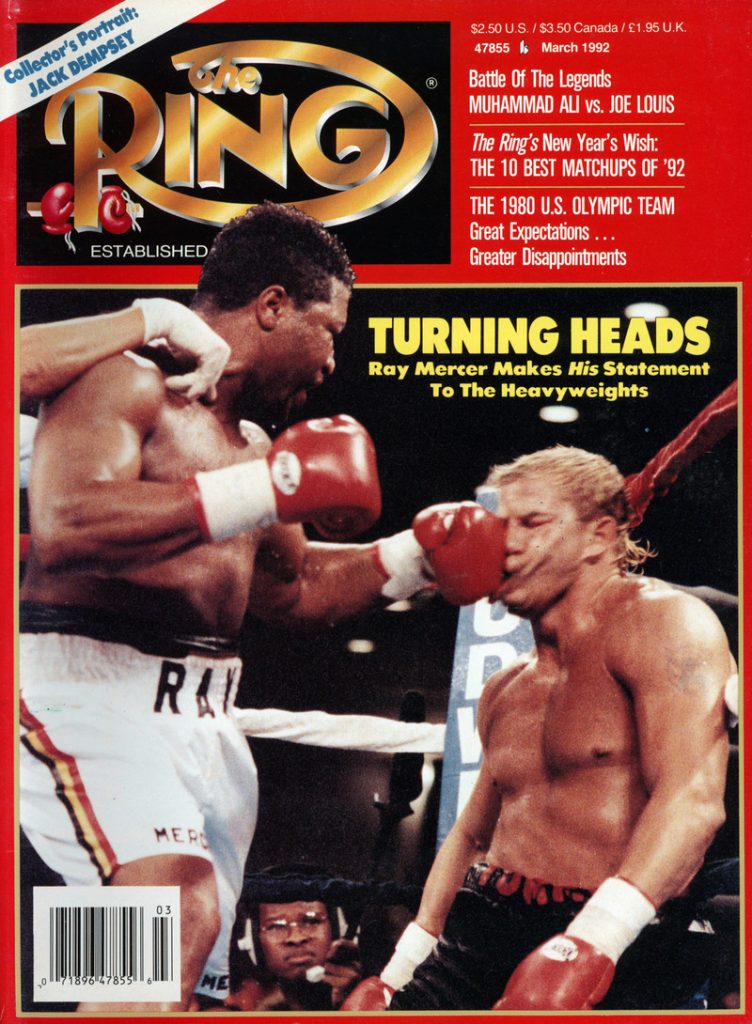

Thirty years ago, on Oct. 18, 1991, heavyweights “Merciless” Ray Mercer and Tommy “The Duke” Morrison squared off in an HBO-televised showdown at Atlantic City’s Boardwalk Hall which presumably would determine if the winner, and maybe even both, had earned the right to enter the pantheon of the division’s true, or at least perceived, elite.

Although each fighter was in the process of establishing his credentials for membership, the exclusive club which Mercer, champion of the then-fledgling and lightly regarded WBO, and challenger Morrison sought to join at that time consisted of just five fighters, all of whom would eventually be enshrined as Hall of Famers in the hallowed halls of Canastota, N.Y.: WBC/WBA/IBF ruler Evander Holyfield, former champs Mike Tyson (who had not yet been convicted of rape, which would sideline him for nearly four years) and comebacking George Foreman, and future titlists Lennox Lewis and Riddick Bowe. Also lurking on the fringes of the Big Five’s level of name recognition and stardom was power-punching Razor Ruddock.

As a stand-alone event, Mercer’s savage, fifth-round stoppage of Morrison – who had dominated the first three rounds and seemingly was on his way to the sort of breakthrough victory that would certify him as the phenom his intriguing life story was making him out to be in the media – was worthy of all the prefight attention. Much had been made in the run-up to the bout that it was a “grudge” match for Morrison, whose nickname was in supposed homage to legendary actor and distant relative John Wayne, whose birth name was Marion Morrison. Although the family link was sketchy at best, and possibly even a figment of some enterprising publicist’s imagination, Morrison certainly was hoping to get some payback for his 4-1 loss to Mercer, a sergeant in the Army, at the 1988 U.S. Olympic Boxing Trials. Mercer not only made the team, but won the heavyweight gold medal in Seoul, South Korea, by scoring a one-round knockout of that nation’s Baik Hyun Man.

It has been 13 years since the 60-year-old Mercer (36-7-1, 26 KOs) last fought. Morrison, whose career essentially was cut short when he tested positive for HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, in February 1996, had three inconsequential and medically inadvisable fights afterward and finished at 48-3-1 (42). He was just 44 when he passed away on Sept. 1, 2013, from the ravaging effects of full-blown AIDS or, to hear his wife Trisha tell it, Guillain-Barre Syndrome, which Morrison also tested positive for in 1996. Other sources indicate that respiratory failure, metabolic acidosis and multiple organ failure were contributing factors in his demise.

If there is one thing that continues to link Mercer and Morrison it is this: despite ring achievements that some would argue are worthy of spots on the IBHOF ballot, if not actual induction, each has yet to have his name go before voters. That could be because they have been deemed unworthy of consideration for solely boxing reasons, or maybe because of their perceived transgressions against their sport and/or polite society in general. That is a matter to be considered later in this story. For now, however, the fight that meant so much to both at the time merits a deeper look.

Photo by The Ring Magazine/Getty Images

Mercer, at 30, was no kid as he approached the “rematch” with Morrison. Given his late start in the professional ranks – due to his nine years of military service, he was just 17-0, with 12 KOs going into that bout, compared to the 22-year-old Morrison’s 28-0 (24). Being an Olympic gold medalist still had its perks for Merciless Ray, whose purse for the fight was $550,000 to $500,000 for Morrison, but it was the younger man who seemingly held every other advantage. The former high school football star from tiny Jay, Okla., was, if not an actual movie star, prominently featured as the ungrateful villain who threw down in a street fight with his mentor Rocky Balboa in 1990’s Rocky V, a cinematic boost to go along with his string of spectacular knockouts and, of course, the constant evocation of his supposed familial ties to John Wayne. Given that Mercer was coming off two hard-fought escapes against his two most recent opponents, Bert Cooper and Francesco Damiani, he stepped inside the ropes as a 6-5 underdog. One major newspaper even had misidentified the proud Army veteran as an “ex-Marine.”

“The thing Ray does best is show he gets beaten up well,” a brash Morrison had said. “Look, Ray’s got one of the best chins in boxing, and certainly he’s got the biggest heart. People like that, it’s not a matter of knocking them down. You have to break their will, make them want to quit. Nobody’s ever done that to Ray before, but I’m going to do it.”

Mercer, to be sure, had his supporters, one of whom was an interested observer, legendary trainer Angelo Dundee. “I love Mercer’s chances,” Dundee opined. “To me, he’s a devastating inside puncher. I noticed that in the amateurs. His footwork is not that fluid, but when he gets inside he can really percolate. Outside, he looks ungainly. But inside, it’s goodbye, Jack. I honestly think he’s going to do a number on Morrison.”

With a crowd of nearly 9,000 expecting fireworks, spectators got them early, and almost exclusively from Morrison, who tested Mercer’s granite jaw with his trademark left hook and ripping uppercuts in dominating the first through the third rounds. But momentum in the scheduled 12-rounder seemed to shift a bit toward the end of the fourth, when Mercer began to engage a seemingly tiring Morrison, who to that point had never been obliged to go more six rounds as a pro. Mercer, who was sporting a red badge of courage, a split lower lip, from the second round on, got Morrison’s attention with a pair of clubbing rights only to have the challenger respond with a left hook that sent bloody spittle spraying from Mercer’s mouth.

Mercer didn’t have everything his own way. Photo by The Ring Magazine/Getty Images

It turned out to be Morrison’s last hurrah. Mercer came right back with another jolting right and, as the bell ending the round sounded with the two men in a clinch, Morrison was gasping for air.

Akbar Muhammad, an adviser to Mercer, interpreted what he had just seen as a precursor of what would soon follow. “Morrison is finished!” Muhammad said, leaping up from his seat in the press section, his arms upraised in exultation. “He’s punched himself out!”

It didn’t take long for Muhammad’s assessment to prove correct. Mercer made a spin move in the corner, connected with a chopping right and, before Morrison could recover, the old Sarge unleashed a 16-punch volley that sent “The Duke” slumping to the canvas. Referee Tony Perez, dispensing with the formality of a count, waved the bout off after an elapsed time of just 28 seconds.

“I’m kind of glad it went like it did,” Mercer said. “You take your man out convincingly, just so people will know he was really out.”

The devastating putaway of Morrison was, perhaps, the signature moment of Mercer’s time as a pro. Stripped of his WBO title for fighting 42-year-old former champion Larry Holmes instead of that sanctioning body’s No. 1 contender, Michael Moorer, Mercer, a 4-1 favorite, then lost a unanimous, 12-round decision to the 42-year-old “Easton Assassin.” But subsequent defeats in marquee matchups with Holyfield, Lewis, Wladimir Klitschko and Shannon Briggs did not impair Mercer’s “Army Strong” reputation as much as what occurred in his first pairing with journeyman Jesse “Thunder” Ferguson on Feb. 6, 1993, in Madison Square Garden. Had he won – and he was overwhelmingly favored to do so – Mercer would have moved on to a $2.5 million payday against WBA/IBF champ Bowe, his ’88 Olympic teammate. But an overconfident and underprepared Mercer came in at a career-high 238¾ pounds and as round after round tolled by in the scheduled 10-rounder, it became apparent to him that that this night was destined to belong not to him, but to the former Tyson sparring partner.

Although that fight was not televised by HBO – which did show the main event, which pitted Bowe against Michael Dokes – boom mikes would audibly confirm that Mercer had, in fact, repeatedly offered Ferguson $100,000 during clinches to purposely lose. Ferguson (who would later lose a rematch with Mercer) declined, won a unanimous decision and was rewarded with a career-high $500,000 payday as the substitute challenger to Bowe. Mercer, meanwhile, was charged with attempted bribery by Manhattan District Attorney Robert Morgenthau, a Class D felony, and could have faced up to seven years in prison had the case gone to trial and his conviction. That didn’t happen, but the damage done to the otherwise pristine image of a soldier who had endured 12-mile hikes while toting an M-16 machine gun on his shoulder, reforger exercises in the snowy woods of Germany and survival tests in desert heat was significant.

Photo by The Ring Magazine/Getty Images

Morrison’s rise to fame, and slide into disrepute, vastly differed from Mercer’s only in the details. A standout tight end and linebacker in high school, he had been offered, and accepted, a football scholarship to Emporia (Kan.) State. The pugnacious kid who got interested in fighting after winning $300, at the tender age of 13, in a Toughman contest, figured his future success as an athlete, if there was to be any, would come on the gridiron.

“When I signed a football scholarship with Emporia state, I figured that was it,” Morrison said very early in his pro career. “No more fighting for me. But (his Native American mother, Flossie) wanted me to enter one last amateur tournament, the Greater Kansas City Golden Gloves, because my older brother and two of my uncles had fought in it and won. It was kind of a family tradition.”

Morrison won that tournament, advanced to the Olympic Trials and, well, “I never did make it to Emporia,” he said. “Things have a funny way of turning out. If I had lost in the Kansas City Golden Gloves, I’d be playing football at Emporia right now. To tell the truth, I never expected to go as far as I did.”

Morrison had already been involved in some of the filming of Rocky V when he went to South Orange, N.J., for a bout with Lorenzo Canady, in which Sylvester Stallone would pretend to be his trainer as cameras rolled for additional footage that might make it onto the final cut. I was in town and at Spectators, a memorabilia-festooned sports bar/restaurant. A young husband and wife were there that morning, hoping to get the autographs of any celebrity athletes who might be in the dining area. It was their good fortune that George Foreman, there to participate in a three-round exhibition, was having a hearty breakfast. The couple procured an amenable Big George’s autograph and happily posed for photos with him before they scanned the room in search of another famous face. The wife saw a blond man across the way and a hint of recognition flashed in her eyes.

“Oh, my goodness, it’s Boomer Esiason!” she whispered to her husband, who like her was wearing a New York Giants jersey. “No,” the husband replied. “It’s Tommy Morrison, the boxer. He’s fighting tonight.”

After getting Morrison to stop eating long enough to pose with them and out of his earshot, the wife turned to her husband and said, “Tell me, is that guy somebody?”

Well, he was, but he never became the somebody that was the goal of Bill Cayton, Morrison’s manager and Tyson’s former co-manager. Cayton yearned to put his then and former client together in a megafight that would break all revenue-producing records. “If everything goes according to plan – namely, that Tommy and Tyson both remain undefeated – a fight between them would be the biggest in boxing history,” Cayton said, almost hyperventilating. “It would be bigger than the World Series, bigger than any sporting event ever.”

March 1992 issue

That fight never happened, although Morrison suppressed his own non-edible appetites long enough to score victories over, among others, Foreman and Ruddock. Perhaps he even could have become as important as Cayton dared to imagine. But he never quite made it that far, for reasons that had nothing to do with what he was capable of doing inside the ring, and occasionally did.

Among Morrison’s missteps was his decision to delay a guaranteed $7.5 million shot at Lennox Lewis to take an interim bout with Michel Bentt, for which he would pick up a quick and easy $1.5 million. On paper, the bout seemed so one-sided that the Vegas sports books declined to post a betting line. The miscalculation borne of Morrison’s arrogance cost him big time as Bentt floored him down three times in the first round, an automatic stoppage given the three-knockdown rule then in effect. Morrison later did challenge Lewis, for a reduced purse, and went out in six rounds, having hit the deck four times.

For all intents and purposes, Morrison’s proclivity for frequent unprotected sex set the stage for what now almost seems to have been an inevitability, his testing positive for HIV prior to a scheduled bout with Arthur “Stormy” Weathers in February 1996. That stunning announcement was not so stunning to Morrison’s longtime trainer, Tommy Virgets.

“I can remember a number of occasions Tommy doing autograph sessions where there might be 1,000 or 1,200 people to go through,” Virgets said. “At the end, he’d come over and show me 15 or 20 notes that were handed to him by women. They had names, addresses, phone numbers, little messages that I’d rather not repeat. It was unbelievable.”

So emboldened was Morrison in his amorous adventures that shortly before the HIV test results that hit him harder than even Lewis had, his answering machine began with the voice of a woman either in the throes of real or simulated orgasm, followed by the fighter coming on and breathlessly saying, “As you can tell, I’m busy …”

Which brings us back to the absence of Mercer and Morrison from the IBHOF ballot, as is also the case with former middleweight and super middleweight champion Michael Nunn, who was 58-4 (38) in a career that seemingly checks all or most of the applicable boxes. But Nunn did hard time for dealing drugs, which would seem to have done nothing to bolster his case for induction. Baseball great Pete Rose is not in his sport’s Hall of Fame because he violated gambling rules, and neither are confirmed or suspected performance-enhancing-drug abusers such as Mark McGwire, Roger Clemens, Barry Bonds and Sammy Sosa. The IBHOF, however, has long professed not to hold non-boxing black marks against Hall-worthy fighters, and even in some instance some boxing-related ones.

In 1991, the year of the IBHOF’s second induction class, executive director Ed Brophy was asked about the possible and even likely enshrinement of Sonny Liston, who had been arrested 19 times before he won the heavyweight title and had indirect ties to organized crime’s two most notorious boxing manipulators, Frankie Carbo and Frank “Blinky” Palermo.

“The Pete Rose situation was raised after our first induction ceremony,” Brophy said at the time. “Our board of directors and screening committee decided that fighters should be judged primarily on the basis of their accomplishments in the ring, not on their personal lives. I did not hear any elector express a problem with Sonny Liston’s candidacy. Our board is very comfortable with the guidelines that were established.”

Perhaps Mercer and Morrison do not meet IBHOF standards for even being on the ballot. Given the parameters cited in 1991 Nunn would appear to be worthy of consideration. As always, the debates and continue.

SUBSCRIBE NOW (CLICK HERE - JUST $1.99 PER MONTH) TO READ THE LATEST ISSUE