Muhammad Ali-Ken Norton 3: Chaos at Yankee Stadium 45 years later

Perfect endings in sports aren’t quite as rare as many fans might imagine. Basketball legend Michael Jordan seemingly crafted his own immaculate farewell when he swished a title-clinching jump shot to beat the Utah Jazz in the closing seconds of Game 6 of the 1998 NBA Finals, giving the Chicago Bulls their sixth and last championship of the Jordan dynasty. In keeping with his innate sense of dramatic timing, Jordan kept his right arm extended upward until and even after the ball dropped through the hoop. It would be the final shot the man known as “Air Jordan” ever took as a Bull.

But it would not be the final shot Jordan ever took as an NBA player as he yielded to the temptation to see for himself if there was more magic to be made, returning after a two-year retirement for two almost desultory seasons with the Washington Wizards. Jordan was still a very good player in D.C., but a somewhat lesser version of himself both individually and as the focal point of another team capable of going all the way to the top, or even part of the way. There are those who believed then, and still do, that his legacy would be even more exalted had he not heeded the siren call of a second comeback that mostly revealed that even gods of the competitive arena can have human frailties.

For boxer Muhammad Ali, maybe the only athlete on Earth who was a more iconic figure in his sport than Jordan was in his, a sacrosanct goodbye could have come, and in retrospect probably should have, on Oct. 1, 1975, when he again waged a physically debilitating, mentally draining war of wills with his foremost rival, Joe Frazier, in the “Thrilla in Manila.” In winning the climactic rubber match of his three-act passion play with “Smokin’” Joe, who, nearly blinded, did not leave his corner for the 15th round, Ali, then 33, achieved the sort of signature moment that Jordan would nearly 23 years later. But such perfect final moments are rare, because, as history has revealed, they are seldom truly final.

As he would demonstrate in the wake of the epic third Frazier fight, Ali spoke of retirement as often as he flicked left jabs, but he could never commit to any of his raft of pledges to permanently step away. “I’m sore all over. My arms, my face, my sides all ache,” he admitted after he and Frazier had again tenderized one another’s body parts to a fare-thee-well. “I’m so, so tired. There is a great possibility that I will retire. You might have seen the last of me. I want to sit back and count my money, live in my house and my farm, work with my people and concentrate on my family.”

Perhaps Ali did not retire after the third go at Frazier because there was much more money to count, more of his people to work with, more fame and adulation for the sporting world’s ultimate narcissist to bask in. Like Jordan the Wizard, he would never again display the full compendium of wondrous gifts that had set him apart from all that had come before or maybe would ever come after his departure. He had followed his close call against Frazier with three relatively ho-hum defenses of his undisputed championship, non-pulse-raising stoppages of Jean-Pierre Coopman and Richard Dunn sandwiched around a unanimous decision over Jimmy Young, an exercise in tedium in which Ali appeared to be old, out of shape and disinterested, in sum incapable of summoning the best of who and what he had been not so very long beforehand.

September 1976 issue

What Ali needed at that particular point in time was to remind everyone of the young, brash, seemingly invincible and self-proclaimed “Greatest of All Time” he steadfastly believed lay semi-dormant within himself. What better opponent to suit that purpose than Ken Norton, the magnificently sculpted former Marine whom he had already fought twice, dropping a 12-round split decision on March 31, 1973, in San Diego, a bout in which an overconfident, underprepared Ali suffered a broken jaw, a defeat he later avenged, at least officially, with a 12-round split-decision victory on Sept. 10, 1973, in Inglewood, Calif. There were more than a few observers who felt Norton should have tagged Ali with a second loss in as many confrontations.

Those bouts, however, were for the fringe NABF heavyweight title. This renewal, still another rubber match, was for boxing’s grandest prize and, well, it could be reasonably hyped as Ali vs. Joe Frazier Lite, Norton not only being The Ring’s No. 1 rated heavyweight contender but also a personal friend of Smokin’ Joe. Because of their close ties, which owed to both of them being trained by the venerable Eddie Futch, Frazier and Norton had vowed to not fight one another, and they never did. It added to the intrigue of Ali’s second trilogy against a formidable foe that Frazier not only predicted that Norton would win, but had offered the opinion that his pal had deserved to win the second segment.

Thus was Ali-Norton III scheduled for Sept. 28, 1976, in boxing’s sacred city of New York, in the House that (Babe) Ruth Built, Yankee Stadium, the site of such great and historically significant fights as Joe Louis-Max Schmeling I, Tony Zale-Rocky Graziano I, Sugar Ray Robinson-Kid Gavilan I, Sandy Saddler-Willie Pep III, Rocky Marciano-Ezzard Charles II, Marciano-Archie Moore and Robinson-Carmen Basilio I, among others.

What’s more, Ali-Norton III also had the distinction of being the first fight to be staged in Yankee Stadium since Swedish challenger Ingemar Johansson, a 5-1 underdog, had dethroned heavyweight champ Floyd Patterson on June 20, 1959. Ingo, incredibly, registered seven knockdowns in that fight, all coming in the third round before referee Ruby Goldstein stepped in and waved off the ongoing bludgeoning.

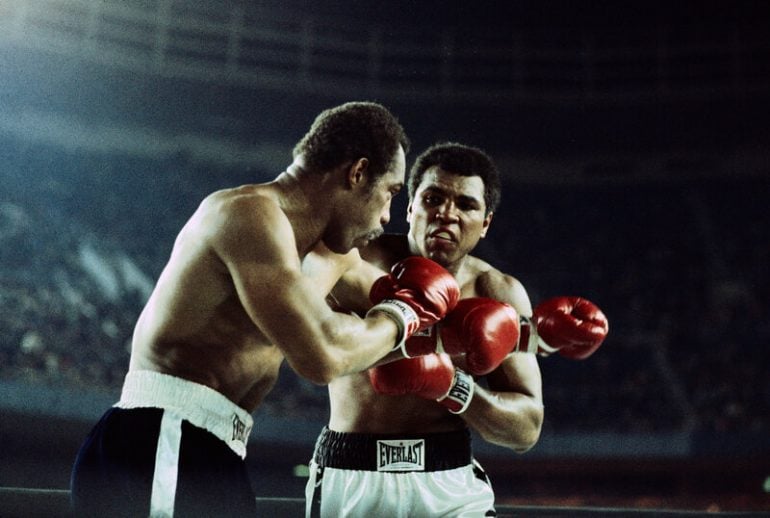

Now, with the 45th anniversary of Ali-Norton III upon us, the thing that mainly sets that clash apart is not what took place inside the ring (many knowledgeable observers panned the action, what there was of it, that played out over 15 mostly forgettable rounds), or the controversy attendant to Ali’s disputed decision over Norton in their second fight, which arguably made a third meeting not only plausible but arguably necessary. It was the out-of-the-ring chaos – out-of-the-entire-stadium, actually – that stamped that night as singularly unique in the annals of boxing, or as close to it as it ever gets in a blood sport where turmoil is hardly a stranger.

Promoter Bob Arum had no way of knowing beforehand of the witch’s brew that would begin bubbling after President Gerald Ford gave a speech in which he said no Federal money would be forthcoming to assist the cash-strapped city. The Oct. 30, 1975, edition of the New York Daily News responded to the snub from Washington with a headline that blared: FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD!

Months would toll by, the crisis incrementally deepening, the most discontented municipal workers being members of the New York City Police Department. Two thousand had been laid off in 1975, and those that remained grumbled that they had not received promised raises and other improved benefits despite being asked to work longer hours to make up for the manpower shortage. Given enough lead time, it might have been possible for Ali-Norton III to relocate to another, presumably more secure city, but promoter Bob Arum and New York officials held firm to the hope that an acceptable solution for all concerned could be effected in time to save the day, and more to the point, the night.

It didn’t happen.

Writer Michael Woods described the deteriorating situation in the Bronx on fight night thusly: Outside Yankee Stadium, it looked like a scene out of the cult classic movie “The Warriors.” The wave of muggings and street crime took place in front of hundreds of off-duty cops who converged at the stadium to protest work conditions.

In his report on the fight for Sports Illustrated, Mark Kram painted an even bleaker word picture of … the dark and mean streets around Junkie Stadium, which erupted into anarchy and savagery.

Even Arum, who was born in Brooklyn and thus was familiar with the alternating heights and depths of life in the five boroughs of his hometown, professed to be amazed by what he had witnessed on his way into the stadium. “It was crazy, you’ve never seen anything like it,” he marveled. “Pockets being picked, watches ripped off.”

Although the announced attendance was 30,298, Arum said that was the pre-sale only. So menacing was the area outside Yankee Stadium that night that many ticket-holders arriving by subway took a look at the milling throngs and promptly returned by train from whence they came. Arum estimated that only 19,000 or so hardy souls actually made it into the ballpark, a number of whom had been relieved of their valuables. Several members of the media complained of having had their portable typewriters stolen.

For those spectators who were able to take their seats, the main event failed to provide the sort of indelible memories of pugilistic greatness that a prime Ali had once provided with regularity. Although he was still too pretty to be a fighter, his handsome face not noticeably rearranged, this Ali did not float like a butterfly and sting like a bee. He lost most of the early rounds to the busier Norton, who carried a six-point lead into the ninth round in Kram’s estimation. But then Norton, believing he was too far ahead on the scorecards to be caught and passed by pencil, made a telling miscalculation by altering his tactics, the most egregious example coming in the 11th round.

“Norton elected to parody Ali, to hang on the ropes, to put his hands down, to exchange repartee,” Kram wrote. “How foolish, how insufferably wrongheaded. It is at this point when he should have been at his most physical, when abandon and fury were called for, when he should have pushed Ali over the edge with the considerable strength left in his superb body.”

At the conclusion of the 15th round, a prematurely gleeful Norton trailed Ali back to his corner, shouting, “I beat you! I beat you!”

Except that he hadn’t. When the scores were read, Ali had pulled out another close but disputed victory, by margins of, in rounds, of 8-7 (twice) and 8-6-1. A stunned Norton, a look of anguish on his face, wrapped a towel around his head and began to cry like a baby.

December 1976 issue

Later, in his dressing room, Norton figured he had fallen victim to the mystique of Ali as much as to the man himself. “I wasn’t even tired,” he complained. “If I had thought it was close, I’d have fought back harder and more. When you fight Ali, you’re behind at the start. It’s obvious you have to knock him out to win. When it’s that obvious, you have to think the judges stole it. They made asses of themselves. The fight speaks for itself.”

Years later, although still convinced he had done enough to win, Norton took a more pragmatic view. He had fought two opponents that night, against Ali the living, breathing human being and Ali the legend. One was beatable, the other clearly not.

“I was very upset at first,” he conceded. “But after I sat down and thought about it, boxing went as Ali went. At that time, Ali was boxing. Boxing wins if Ali wins. As for the controversial decision, I’ve forgotten it. I can’t do anything to change it.”

As for Ali, he said the decision for him was entirely justifiable, and in keeping with boxing tradition. “You got to beat the champ, you gotta whup him!” he exclaimed. “Did he beat me convincingly? I had to beat Joe Frazier twice, Sonny Liston twice, George Foreman. You can’t fight like Jimmy Young. You got to whup the champ! Drop me! Make me fall! Hurt me! Do you think I paid the judges? They never give me anything. I’m not a good American boy. I’m an arrogant n—–. They wouldn’t give it to me if I didn’t win it.”

A bit later on, his fervor of the moment tamped down, Ali again did the retirement shuffle that would become a standard part of his post-Manila patter “I got $6 million tax-free saved up,” he told Kram. “Drawin’ seven percent interest. What I gotta keep fightin’ for? Best for me to get out now. There’s nothin’ else to prove. This (boxing) thing is dangerous.”

In the end, the boxing thing proved dangerous. Ali stuck around for six more fights after his rubber-match edging of Norton, the last of which was a 10-round unanimous-decision loss to Trevor Berbick on Dec. 11, 1981, in the Bahamas. Ali was not only a shadow of his magnificent best in that bout, but a shadow of the fighter he had been in the third go-round with Norton. It can only be presumed that the many years in which his physical essence ebbed away from the effects of Parkinson’s Syndrome is a direct result of having remained too long in harm’s way.

“At that point (the third fight with Norton) I thought he should have ended it after the third Frazier fight,” opined Jerry Izenberg, the longtime sports columnist for the Newark Star-Ledger.

But the most prevailing image of Ali, who was 74 when he died on June 3, 2016, shall always be that of the sleek, impossibly fleet of fists and feet fighter who, at the height of his powers, might have been exactly what he claimed to be. In that regard he is no different than Willie Mays, who is more remembered for the unbridled joy of his play on baseball diamonds as the “Say Hey Kid” rather than his stumbling under fly balls as a middle-aged centerfielder for the New York Mets, or Joe Namath, forever the golden-armed quarterback for the Super Bowl III-winning New York Jets instead of the hobbled version of himself dropping back to pass on wrecked knees as a Los Angeles Ram.

SUBSCRIBE NOW (CLICK HERE - JUST $1.99 PER MONTH) TO READ THE LATEST ISSUE