Sandy Saddler-Willie Pep 4: The foul-filled final chapter 70 years later

Imagine, if you can, Russian ballet great Rudolf Nureyev dancing Swan Lake while wearing snowshoes … Michelangelo doing his best to adorn the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel using only his thumb and a kindergartner’s water paint … legendary tenor Luciano Pavarotti performing La Boheme with a mouthful of marbles.

True artists can be found in almost all forms of human endeavor, but their particular masteries can be and sometimes are affected by a lack of proper tools or distracting outside influences. And so it notably was in a select few instances for the late two-time former featherweight champion Willie Pep, arguably the most accomplished defensive boxer of all time, so gifted at the nuances of spacing and movement that he once was said to have won a round against a flummoxed opponent without throwing a single punch.

Pep – born Guglielmo Papaleo in Middletown, Conn., on Sept. 19, 1922 — was so convinced he could pull off that improbable stunt that he reportedly advised a few favored sports writers of his plan before he was to take on Jackie Graves on July 25, 1946, in Minneapolis, Minn. He told them to pay close attention to what he would do in the third round, which was to make Graves look like a blindfolded man trying to capture a butterfly with a pair of tweezers, and what he wouldn’t do, which was to intentionally hit his lunging, stumbling, ineffectual foil. And damned if Pep, who won the round, didn’t do exactly what he had vowed.

July 1949 issue

Then again, maybe it didn’t happen that way. Perhaps the tale of Pep’s victorious no-punch round is nothing more than urban legend, a flight of fancy that took root and remains plausible because, well, Pep was Pep. There is no existing film of that fight, and a report of it in the Minneapolis Star described the third round as “toe to toe slugging with Pep inflicting his best punishment with a right to the body.” But as a fictional Old West newsman remarked in the 1962 film The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” And so one of the compliant legend-crafters, Don Riley, wrote that Pep had put on “an amazing display of defensive boxing skill so adroit, so winning, so subtle, that the roaring crowd did not notice Pep’s tactics were completely without offense. He even made Sugar Ray Robinson’s fluidity look like cement hardening.”

And this, from writer and ring historian Bert Sugar: “Pep moved, switched to southpaw, mocking Graves; Pep danced, Pep weaved; Pep spun Graves around and around again; Pep gave head feints, shoulder feints, foot feints, and feint feints. But Pep never landed a punch.”

Having presumably proved his point, Pep went on to display his dominance in a more traditional fashion, flooring Graves (who was no stiff; his career mark was 82-11-2, with 48 KOs) nine times en route to winning on an eighth-round technical knockout.

But even the best of the best are sometimes thrown off their game on a given day. Nureyev might not have danced so magnificently if he were bothered by, say, a bunion on his big toe. Before the invention of modern over-the-counter medications, Michelangelo might have applied an errant brush stroke or two if he woke up one morning with nagging joint pain in his painting hand. Even Pavarotti’s incredible voice could be rendered less so by laryngitis. And so it was for Willie Pep, the “Will o’ the Wisp,” to whom a similarly accomplished but stylistically opposite featherweight, Sandy Saddler, served as kryptonite to the defensive genius’ fancy-stepping but less-powerful Superman.

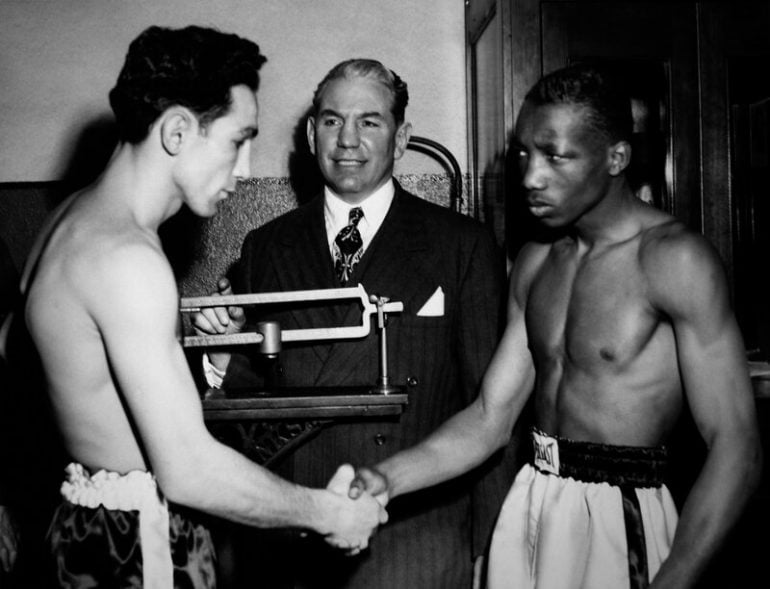

Today marks the 70th anniversary of the fourth and final installment of the bitterly contested arch-rivalry that pitted Saddler, again the reigning featherweight titlist, against the normally elusive Pep, whose hit-and-don’t-get-hit tactics once again would be discarded either by chance or choice. The previous three matchups – two of which had been won by Saddler – were marked in no small part by Saddler’s ability to get Pep to meet him on his preferred terms, which involved much more give-and-take exchanges favorable to the harder-hitting Harlem resident, in addition to being indisputably down ’n’ dirty. Holding and hitting? Oh, yeah. Heeling? Gouging? Thumbing? Arm-twisting? Hitting to the back of the head? Yes, yes, yes, yes and yes.

It was considered a major upset when Pep, the absolute king of the 126 pounders, relinquished his slew of titles (NBA, NYSAC and The Ring) to Saddler via fourth-round knockout in their first meeting, on Oct. 29, 1948, in Madison Square Garden. Most knowledgeable observers had expected to Pep to win, and why not? He had entered the ring for that bout with a glittering 135-1-1 (45) record, on a 73-bout undefeated run that included a solitary draw, and the prevailing opinion was that the Will o’ the Wisp would also school Saddler, the son of West Indian immigrants who came in at 75-6-2 (57) and with a bit of a reputation for rules-flouting. Noted British fight scribe Harry Mullan once referred to Saddler as “a highly refined master of the ignobler aspects of the Noble Art. There have been few better featherweight champions, and even fewer dirtier ones.” From the opening bell, however, it was Saddler who roughly imposed his will, breaking Pep down with ripping shots as no one ever had.

There would, of course, be a rematch, on Feb. 11, 1949, also at Madison Square Garden and before a packed house of 20,000. It would be a stark reversal of what had happened in the first pairing, with Pep again the slippery escape artist, darting in to score with quick flurries whenever it suited his purpose before ducking and dodging his way back out of the danger zone. Pep would forever claim thereafter that his unanimous, 15-round decision over his most persistent nemesis was the finest performance and most cherished victory of his 26-year, 241-bout, 1,956-round professional career.

With the series now square at one victory apiece, public interest in a rubber match was such that a paid crowd of 37,781 turned out on Sept. 8, 1950, in Yankee Stadium, with Saddler, interestingly, going off as the 8-5 betting favorite. But try as he might to replicate his success in Part 2, a frustrated Pep, clearly in distress, retired on his stool after the seventh round due to a dislocated should he claimed was the result of Saddler’s wrestling maneuvers.

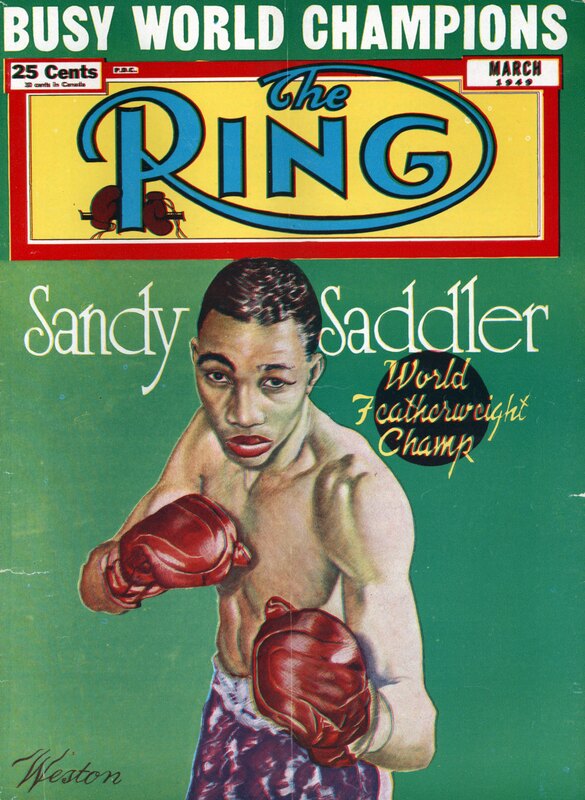

March 1949 issue

As the winner of two of the three previous matchups, both of his triumphs marked by an ability to frequently manhandle the smaller Pep, Saddler again went off as the favorite for their fourth and final meeting, this time by 9-5. But the climactic showdown at New York’s Polo Grounds included an element, a mutually intense personal dislike, which was much more apparent than had been evident previously. This time Pep would not have to be bullied or coerced into fighting Saddler’s fight, he would willingly give vent to his desire to inflict as much or more pain than he was apt to receive, no matter how strategically imprudent that was.

The press corps that had once rhapsodized about Pep’s Fred Astaire-in-padded-gloves style, along with a live audience of 13,868, were aghast by what took place from round one until the finish, with Pep, badly bleeding from a gash above his right eye opened by a Saddler left hook in the second round, declining to leave his stool at the end of the ninth round. The only difference from Pep’s third go at Saddler was the nature of the injury that precipitated his grudging surrender.

“He kept sticking his thumb in my eye,” complained Pep, who was ahead on the scorecards submitted to that point by referee Ray Miller (five rounds to four) and judge Frank Forbes (5-4), with judge Arthur Aidala seeing it as a 4-4-1 standoff. “Every time we clinched he gave me the thumb, in the cut and in the eye. I couldn’t stand it. I hate to make excuses but I couldn’t stand it. Bill (Gore, his trainer) kept telling me I was winning, but I couldn’t stand the pain in my eye.”

It can be argued, convincingly, that Pep’s place in the annals of boxing is and should be higher than that of Saddler, although both were charter inductees into the International Boxing Hall of Fame’s Class of 1990. But man-to-man, the proof is in the pudding. Head-to-head, Saddler’s three victories in four clashes with Pep offers conclusive evidence of who owned whom inside the ropes.

Bill Lee, sports editor of the Hartford Courant, expressed that opinion when he wrote:

Sandy Saddler is Pep’s master. He proved it Wednesday night to the satisfaction of everyone who saw the fight. He convinced Lou Viscusi, Pep’s manager, and Bill Gore, the trainer, that he is the one fighter in Pep’s life that Willie can’t handle.

Having gone to that particular well four times, Viscusi acknowledged the reality that there need not be a fifth time for his guy, Pep, to further test himself against the taller (5’8½” to 5’5”), longer-armed (70” reach to 68”), harder-hitting and four-years-younger Saddler. “Every fighter has bumped into one man he can’t lick,” Viscusi reasoned. “I’m convinced now that Pep can’t beat Saddler.”

What stung both future Hall of Fame fighters, even more than the legal or illegal punches that were landed, was the negative reaction to their anything-goes violation of acceptable ring etiquette. Even jaded sports writers professed to be shocked and dismayed by what they had seen, with Pep designated for even more withering criticism than Saddler.

Jimmy Cannon, of the New York Herald Tribune: There was a time when Willie Pep fought with a mixture of proud caution and audacity. The fight racket was improved by his graceful agility which was as true and clean as this cruel form of entertainment can ever but. But (his) splendid skill has deteriorated into a nastiness which resembles the guile of a clumsy card cheater. The tricks Pep used in the Polo Grounds last night were low and snide. It was shameful to behold.

Gene Ward, New York Daily News: Wrestling, holding and otherwise trying all the tricks to stave off the inevitable, that once-great ring magician, Willie Pep, went down to ignoble defeat while sitting on his stool at the Polo Grounds at the end of the ninth round of a weird and dreary apology for a fight.

Lester Bromberg, New York World Telegram: Smarty pants (Pep) suckered the public again as he blew taps for himself in the corner last night at the Polo Grounds, capping a nightmare of pugilism as it ain’t.

Al Abrams, sports editor of the Pittsburgh Post-Garette: It was nine rounds of the worst exhibition of unsportsmanlike conduct ever seen in a bout anywhere.

Jim Jennings, New York Mirror: Pep, who employed every dirty trick known to the racket, quit suddenly while seated in his corner. In more than 40 years of watching fights, I never viewed a fouler battler than Pep. Tripping, holding and gouging were just a few of his mean stunts.

Adding insult to injury for Pep was the decision by newly installed New York State Athletic Commission chairman Robert K. Christenberry to suspend Pep for life and Saddler indefinitely. Pep’s suspension was lifted after 20 months, and both went on to resume their careers. Although Saddler’s last bout was a 10-round unanimous-decision loss to Larry Boardman on April 14, 1956, when he was not quite 30 years old, Pep kept on keeping on until he was 43, finally retiring following a six-round defeat on points to Calvin Woodland on March 16, 1966.

Asked why he lingered so long in a harsh sport unforgiving to even elite fighters who ignore the inevitable ravages of time, Pep, who was married six times and was fond of betting on racehorses that tended to run slower than he would have preferred, cracked, “My ex-wives were all good housekeepers. When they left, they kept the house.”

To both of their credit, Pep and Saddler – as is often the case with fighters who have gone to hell and back, maybe even several times – became friends in later life. Sadly, both men passed away with their memories of who and what they had been largely erased. Pep (career record: 229-11-1 [65], who was 84 when he took his eternal 10-count on Nov. 23, 2006, suffered from Alzheimer’s the last five years of his life; Saddler (145-16-2 [104],was 75 when he died on Sept. 18, 2001, also afflicted by Alzheimer’s.

READ THE LATEST ISSUE OF THE RING FOR FREE VIA THE NEW APP NOW. SUBSCRIBE NOW TO ACCESS MORE THAN 10 YEARS OF BACK ISSUES.