A quarter-century ago, first Bowe-Golota fight could have been a great upset instead of just upsetting

Not long after the first pairing of former heavyweight champion Riddick Bowe and Andrew Golota were central figures in an almost-classic upset that devolved into one of the most notorious incidents in boxing history, Larry Hazzard Sr., executive director of the New Jersey State Athletic Control Board, mused about the potential positives that were obliterated by the ugliness of the post-fight riot that had taken place the evening of July 11, 1996, in Madison Square Garden.

“What boxing needs is a high-visibility fight where an underdog pulls off a big upset,” said Hazzard, almost prophetically given what would transpire in the virtual reenactment of the original in the Bowe-Golota rematch in December of that year. “I love upsets. Look at all the excitement that was generated when Buster Douglas knocked off Mike Tyson in Tokyo. And you know what? We almost had that a few weeks ago. Andrew Golota beating up Riddick Bowe in the Garden was the closest thing we’ve had to Douglas beating up Tyson. It could have been the most spectacular night boxing has had in some time. Instead, it disintegrated into a disqualification loss and a post-fight riot. Almost instantly, something great became something horrible. Upsets are good, but riots are definitely not good.”

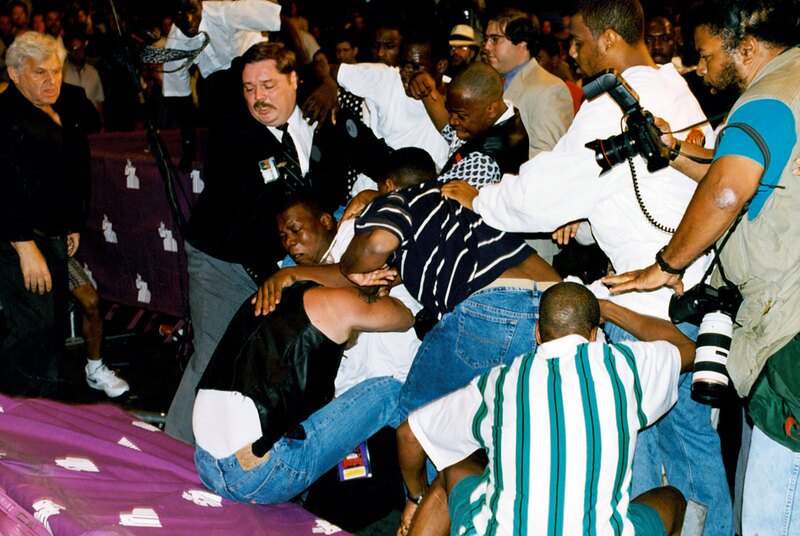

Golota, a 12-1 underdog seemingly was on his way to a career-defining victory he was unlikely to lose on the scorecards despite being docked three penalty points for repeated low blows, fired one punch too many into Bowe’s not-so-protective cup in the seventh round of the scheduled 12-rounder. Grimacing in pain, “Big Daddy” crashed to the canvas in clear distress, prompting referee Wayne Kelly to immediately wave an end to the foul-fest and anoint Bowe the winner by DQ. And when members of Bowe’s unwieldy entourage, led by his enraged manager, Rock Newman, rushed into the ring to confront Golota and his corner team, the extracurricular action spilled over into the spectator seats with more than a few fans of the two fighters exchanging blows – the paid attendance was 11,252 – which contributed to a melee that lasted 36 minutes, or until the Garden’s overwhelmed security detail were joined by NYPD officers called in to provide assistance.

The melee transfers from inside the ring to outside. Photo by The Ring Magazine/ Getty Images

Among the casualties was Golota’s 74-year-old trainer, Lou Duva, who was trampled during the mob scene inside the ropes. Duva, now deceased, had a history of coronary trouble and was rushed by ambulance to NYU Hospital, where he was reported to be in stable condition. All in all, maybe Duva was fortunate; the tally when all was said and done was 16 arrests and 22 injuries. One woman seemed to have gotten the worst of it, wandering around with both eyes nearly swollen shut and crying out to no one in particular, “Look what they did to me!” Six days after the bout, three Brooklyn men filed a $4.5 million lawsuit against the Garden, Bowe and Newman, claiming in court papers they were run over, punched and stomped in the mass confusion.

As the 25th anniversary approaches of a date that shall forever live in pugilistic infamy, fight fans again are reminded of how thin the line can be between the exhilaration of attending a much-anticipated sporting contest and anarchy. Fingers of blame were quickly pointed, with more than a few aimed at Newman, who was socked with a $250,000 fine and a one-year suspension. It did seem logical that Newman was depicted as the principal agitator; he literally had to step over the prone form of his fighter in his dash toward Golota after the DQ was announced. Another Bowe aide, Bernard Brooks Sr., pushed Golota from behind, with Golota responding with a backhanded slap at Brooks. Someone – at various times identified as Brooks’ son or Jason Harris – clubbed Golota in the back of the head with a walkie-talkie, drawing blood.

“You’ve got to stop a situation like that before it starts,” Howie Albert, a former official with the New York State Athletic Commission, said of something he believed, with the benefit of hindsight, to be preventable. “(Bowe) had an entourage of, what, 20 guys? Ridiculous. You should have only the corner people in there, period.”

Photo by The Ring Magazine/ Getty Images

It should be noted, however, that there was ample guilt to be distributed on both sides. While Bowe had his private parts tenderized by a raft of illegal punches, and had to endure the sight of his mother, Dorothy Bowe, in near-hysterics, he was, after all, pronounced the winner of a fight in which he might not have been wholly prepared to succeed for conventional reasons. Two days prior to the fight, he weighed in at a then-career-high 252 pounds, 17 more than he had in capturing the championship in his first matchup with Evander Holyfield on Nov. 13, 1992.

“He had to be at least 260 when the fight started,” Tim Witherspoon, another former heavyweight titlist with a history of losing battles of the bulge, said of Bowe. “I could tell from the first round it was going to be a long night for him.”

It soon became apparent that Golota, a fellow medalist in the super heavyweight division at the 1988 Seoul Olympics – Bowe took the silver (the gold went to Lennox Lewis) with Golota, representing his home country of Poland, coming away with a bronze – was on his way, as Hazzard had suggested, to crafting the sort of magical performance that Douglas had turned in against Tyson in 1990. Punch statistics compiled by CompuBox showed him connecting on 243 of 440, an extraordinarily high 55.2 percent, to 143 of 361 (39.6 percent) for Bowe.

Even despite Kelly’s point deductions the fourth, sixth and seventh rounds, Golota led by 67-65 on two of the three official scorecards and by 67-66 on the other. If only he had elevated his target areas to Bowe’s chin and ample midsection instead of below the waistband, he should have been home free, maybe even winning by knockout.

“The kid was winning the fight from here to China,” Albert said of Golota. “He was beating Bowe up.”

But the biggest obstacle to Golota winning, on this night as in future ones, proved to be the reflection of the guy he saw when he looked in the mirror, not the fighter in the other corner. Golota had been dubbed “The Foul Pole” by New York boxing writer Michael Katz, an uncomplimentary but entirely accurate nom de guerre indicative of his propensity for straying outside the rules either unintentionally or with malice aforethought. Among his transgressions were the time he chomped on Samson Po’uha’s neck in their May 16, 1995 bout, for which Golota was not penalized and won by fifth-round stoppage, and his flagrant head-butting of Danell Nicholson on March 15, 1996, a bout for which he also was not penalized and won via fifth-round TKO.

Heading into fight one, Bowe viewed Golota as easy work. Photo by The Ring Magazine/ Getty Images

Bowe was aware of Golota’s track record for rules-bending and occasionally breaking, and he had vowed ahead of time that he would match him dirty deed for dirty deed if necessary.

“If he bites me or butts me, he’s going to get a nasty tail-whipping in return,” Bowe promised, apparently forgetting to add low blows to the list of infractions he anticipated. But Big Daddy’s eye-for-an-eye threat, or maybe testicle-for-testicle, was not carried out. Round by round he was being beaten to the punch, fairly and otherwise. He couldn’t possibly win … until, of course, he did through Kelly’s appropriate if somewhat delayed intercession.

What followed was a black eye for a sport that didn’t need any more such shiners.

“I was here in 1979 (for a fight between Edwin Viruet and Esteban de Jesus) when shots were fired,” Steve Farhood, a former editor of The Ring, said by way of comparing two of the sweet science’s darker travesties. “But even that didn’t compare to this. This could be the last night of boxing at Madison Square Garden.”

Thankfully, that has not been the case. Nor was Bowe-Golota II, a scheduled 10-round pay-per-view affair on Dec. 14, 1996, in Atlantic City Convention (now Boardwalk) Hall, the death knell for fights in that seashore town. But it was, amazingly enough, a case of lightning striking twice in the same manner, a Powerball-sized improbability that even today defies logic. There really couldn’t be any way Golota could be manhandling Bowe again, and get himself disqualified a second time?

Yes, indeed, the Foul Pole again revealed himself to be a creature of disconcerting habit. Despite being hit with a pair of point deductions, one for an intentional head-butt in addition to the standard subtraction for a low blow, Golota – a leopard apparently incapable of changing its spots — slammed Bowe with two punches well below the waist band in the ninth round. Down Bowe went, and once he arose, grimacing and adjusting his crotch, he had his hand raised in triumph.

My story in the Philadelphia Daily News tried to explain the unexplainable: “One disqualification loss had cloaked Golota in an air of mystery; two have marked him as some sort of wacko, as harmful to himself as he is to opponents.”

Another Bowe-Golota fight, another DQ. Photo by The Ring Magazine/ Getty Images

As more time passed, the divergence of the paths traveled by Bowe and Golota became, depending on one’s point of view, clearer or murkier. Golota continued to perplex those who believed in his physical talent but couldn’t fathom the inner workings of a conflicted mind. Even after the back-to-back DQ defeats against Bowe, he snagged a shot at WBC heavyweight titleholder Lennox Lewis on Oct. 4, 1997, losing on a first-round knockout. One media member quipped beforehand that the public should come out to “watch a fight for the heavyweight crown, and the family jewels.” This time, however, Golota didn’t last long enough to get the opportunity to jolt LL’s jewels.

Two other bouts did much to impair Golota’s fraying reputation. One was his 10th-round TKO defeat to Michael Grant, whom he had dominated from the start of the scheduled 12-rounder on Nov. 20, 1999. Once floored in the fateful 10th, Golota, who had beaten the count and was well ahead on points, declined to continue. A similar situation occurred when he squared off against fellow rules-flouter Mike Tyson on Oct. 20, 2000, in Auburn Hill, Mich., a promotion that was billed as “Bad Boys.” On that occasion, Golota refused to come out for the third round, claiming Tyson had not been penalized for head-butting him.

“I’ve never seen a more blatant act of cowardice (in the ring),” Showtime executive Jay Larkin complained of Golota, whom he said would never again appear on the pay-cable network. Tyson’s trainer at the time, Tommy Brooks, had a different opinion, stating that “I truly believe that Andrew is not a coward. I think he suffers anxiety attacks and I believe he was having one of those.”

Golota, now 53, quit the ring after losing by sixth-round stoppage to Przemyslaw Saleta on Feb. 23, 2013, in Gdansk, Poland. Officially, his final record is 41-9-1 with 33 wins inside the distance, although a case can be made that two of his defeats, and possibly three or more, were as much self-inflicted as anything done by opponents. He has never been on the ballot for the International Boxing Hall of Fame, an honor he doesn’t deserve for a number of reasons, and whatever case that could be made for his being deserving of IBHOF consideration, if only he had been able to harness and control his inner demons, shall forever remain a matter of conjecture.

Bowe, also 53, is an IBHOF inductee, Class of 2015, and on merit. His record shall forever stand at 43-1, with 33 KOs, but some observers will continue to wonder if he could or could not have turned the course of his two encounters with Golota around had not he been on the wrong end of too many blows that strayed far south of allowability.

All that is absolute is the fact that 25 years ago, a chapter of boxing history was authored that perhaps should never have been written quite the way it was. But then all history is riddled with variables, isn’t it?

SUBSCRIBE NOW (CLICK HERE - JUST $1.99 PER MONTH) TO READ THE LATEST ISSUE