Joey Giardello’s win over old Sugar Ray did have historical implications

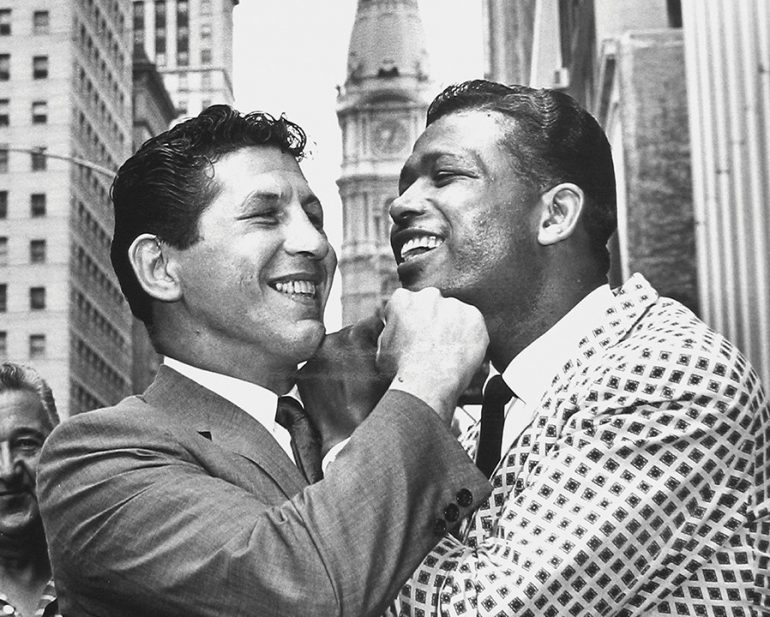

It was a fight not deemed important enough to be shown on television or even carried on radio. One fighter was considered to be old at 33, after 123 professional bouts, and the other downright ancient at 43, after 169 ring appearances and increasing evidence that he was but a shadow of his former brilliance. But Joey Giardello’s 10-round unanimous decision win over a faded but still dangerous Sugar Ray Robinson in Philadelphia’s jam-packed Convention Hall on June 24, 1963, nonetheless, had historical implications.

Had Robinson won – and a lot of people were hoping he would reach back into his glorious past and make magic one more time – he almost certainly would have earned a shot at his sixth ascension to the middleweight championship, then held by Ring Magazine, WBC and WBA titlist Dick Tiger. Were Giardello – a slight 7-to-5 favorite – to win in his adopted hometown, all signs pointed to him getting the date with Tiger, the formidable Nigerian who was in the process of enhancing his own Hall of Fame credentials. Giardello had come up barely short in a previous bid for the 160-pound world crown, Gene Fullmer retaining the National Boxing Association version of that belt on a split draw on April 20, 1960, in Bozeman, Montana, an outcome vigorously disputed by Giardello. More than a few knowledgeable observers also felt that Giardello deserved better than a title-depriving standoff.

A frustrated Giardello – whose birth name was Carmine Tilelli; he used the birth certificate of a cousin to surreptitiously skirt the minimum-age requirement and join the U.S. Army at 16, serving underage in an Airborne unit for the brief remainder of World War II – came to believe he might never get a second opportunity to fulfill his dream of making it all the way to the top of the middleweight mountain. That feeling of being boxed out was at least somewhat understandable; Giardello (he turned pro shortly after turning 18, retaining his Army pseudonym for professional purposes), took on all the dangerous black fighters that were routinely ducked by some other white contenders. He had already split a pair of non-championship decisions with Tiger, gone 2-1 against Ralph “Tiger” Jones, split two fights with Henry Hank, beaten Jesse Smith twice and Gil Turner once, with a loss to George Benton.

“He was the greatest middleweight ever to come out of this city, I don’t care what anybody says,” longtime Philly boxing promoter J Russell Peltz said upon the revelation that Giardello would be enshrined in the International Boxing Hall of Fame’s Class of 1993. “Joey didn’t duck anybody and he never backed down from anybody. He was one of the few white fighters who fought all the tough black fighters.”

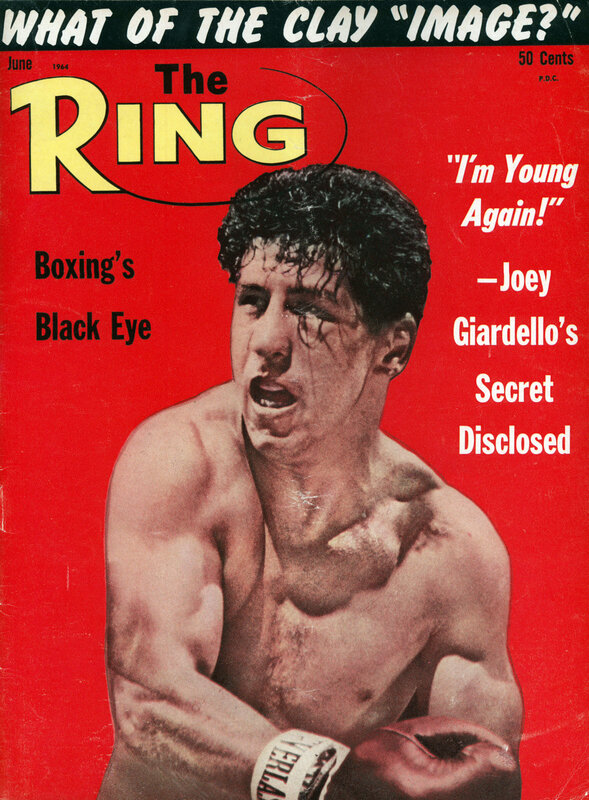

June 1964 issue.

All of which raises a question: Would the Brooklyn-born Carmine Tilelli, who fell in love with a teenaged beauty named Rosalie, married her and relocated to her hometown of Philadelphia, along with his purloined name, after WWII, have gained the approval of IBHOF voters had he not gone on to dethrone Tiger on points (referee Dick Cavalier, the sole arbiter, saw Giardello as the winner by 8-5-2 on rounds) in Atlantic City on Dec. 7, 1963, after his victory over Robinson? There are those who would point out that there are few IBHOF “Modern” inductees who failed to drape themselves in the cloak of a world champion at some point. Oh, sure, Giardello might have joined Charley Burley and a select few others to have their future ticket to Canastota, N.Y., punched without the benefit of a reputation-enhancing title, but then again …

“All I want is Dick Tiger. I want another shot at the championship,” Giardello said after he had cleared the Sugar Ray hurdle by margins of 49-43 (referee Buck McTiernan, on the five-point must system then in effect), 48-45 (judge Lou Tress) and 47-43 (judge Bob Polis).

In some part because Giardello-Robinson was off TV, the purses for the main-event fighters was embarrassingly miniscule by 21st-century headliner standards: $17,000 for Sugar Ray, $15,000 for Giardello. (The live gate was just $59,097.74.) But given the enduring appeal of SRR, arguably the greatest pound-for-pound fighter of all time, and Joey G’s hometown hero status, an official paid crowd of 8,598 filled the Convention Hall seats. Well, at least most of them were ticket-purchasers; hundreds of gate-crashers broke down two doors and poured into the arena through the restaurant in a mini-version of what would happen at Woodstock in 1969, much to the consternation of promoter Herman Taylor.

Was it a great fight befitting two future Hall of Famers? Perhaps not, but it was not without its highlights. Giardello, trained by Adolph Ritacco, followed instructions and went aggressively at Robinson from the opening bell, a strategy based on the presumption that the aging, well-worn legend, despite having come in on a five-fight winning streak, would marshal his energy so that he’d have something left for the later rounds, if needed.

Sugar Ray’s slow start did, in fact, prove costly. Aware that he was increasingly falling behind on the scorecards, the only man ever to win the world 160-pound championship five times correctly concluded that he needed to step it up, and fast, as the bout entered the seventh round. He had two of his better rounds in the seventh and eighth, and clearly hurt Giardello with a jolting overhand right in the eighth. A tiring Robinson couldn’t sustain his rally, however, his pace slackening in the ninth and 10th rounds.

When it was over, Giardello embraced the man he had long held in deservedly high esteem, telling him, “Ray, you were always an idol of mine and tonight didn’t change that. You must have been some helluva fighter when you were at your best.”

A disappointed Robinson, seemingly aware that his late-career quest to extend his number of middleweight reigns to six would go unfulfilled, said, “I’m not sure what my future plans are. I can’t make up my mind now. I coasted in the beginning, and that was my big mistake.”

Giardello’s post-fight comments concerning Robinson were alternately complimentary and a bit disparaging. He knocked down the Sugar man with a left hook in the fourth round, but Robinson arose at the count of four and fought on.

“I knew I was in with a good fighter when those body punches didn’t slow him down,” Giardello said in tossing a verbal bouquet to his vanquished opponent. “And he’s a smart fighter. Look at the way he threw that right-hand lead at my head to open the eighth. It was great, but I was expecting something like that all through the fight. Don’t sell this guy short – even if he is getting old – he can fight any middleweight around today and beat them.”

That bit of praise was countered by another utterance from Giardello, who offered that SRR “was a great champion. It’s a shame his reflexes are gone now.”

Fifty-eight years have passed since Giardello and Robinson squared off in a crossroads fight that meant a great deal to the winner but could have meant just as much and possibly more had the loser emerged victorious. How much more in awe would generations of fight fans have held the original Sugar Ray had he challenged and beat both Tiger and Father Time to win a mind-boggling sixth middleweight championship? Robinson did as he said he would, which was to consider his future plans, and his choice was to keep on fighting even as his remarkable skills continued to deteriorate.

Five-plus years removed from Robinson’s fifth and final time to assume his place upon the middleweight throne, accomplished when he took back the scepter from Carmen Basilio on a 15-round split decision on March 25, 1958, his post-Giardello resume had him going a seemingly respectable 19-6-3 (with one no-contest). But, upon inspection, during that span he drew twice with Fabio Bettini and once with Art Hernandez, while losing twice to Stan Harrington, and once apiece to Memo Ayon, Mick Leahy, Ferd Hernandez and, in his final bout on Nov. 10, 1965, Joey Archer. None of those fighters would have stood any kind of chance against an in-his-prime Sugar Ray. SRR’s final record stands at 174-19-6, with 109 wins inside the distance, in a career that began in 1940. Ironically, Robinson – born Walker Smith Jr. – fought entirely as a pro under a pseudonym that boxing buffs forever shall know him by. He was 67 when he passed away on April 12, 1989, in Culver City, Calif., his memory wiped clean by the progressive effects of Alzheimer’s disease and his physical health also wrecked by diabetes.

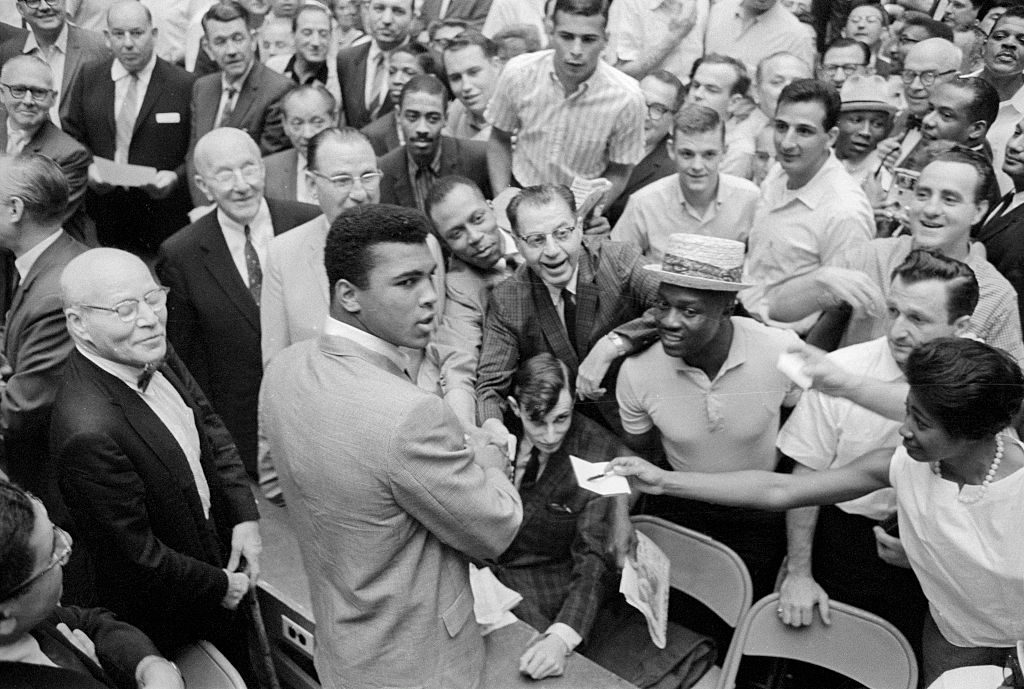

ORIGINAL CAPTION: Muhammad Ali (then Cassius Clay) is mobbed by enthusiastic fans at ringside of the Robinson-Giardello fight.

Muhammad Ali – who, somewhat ironically, was in the audience for Giardello-Robinson — always paid homage to Sugar Ray, proclaiming him as “the king, the master, my idol.” Giardello, who, like a future Philly-based middleweight champ, Bernard Hopkins, always found a way to convert every little slight into fuel for his inner fire – didn’t bother to hide his displeasure when Ali, still known then as Cassius Clay, entered the ring before the fight that night to take a bow, and showed great reverence toward Robinson while pointedly ignoring Giardello. Clay then loudly disparaged Giardello throughout the fight as well.

After snagging his title shot against Tiger, Giardello, as a 4-1 underdog, turned in one of his finest performances and, no doubt, strengthened his future claim to IBHOF membership. And although he successfully defended the championship just once, a 15-round unanimous decision over black challenger Rubin “Hurricane” Carter on Dec. 14, 1964, in Philly’s Convention Hall (he relinquished it in a rematch with Tiger, on a UD15 on Oct. 21, 1965, in Madison Square Garden), the Carter match was a focal point in the 1999 biopic about Carter’s life, The Hurricane, that sequence inaccurately portrayed the nod for Giardello to be the result of a racial robbery. Giardello sued, received a substantial out-of-court settlement, and as part of the deal the film’s director, Norman Jewison, admitted in the DVD that the truth of that bout might have been hedged a bit. Or quite a lot, actually.

Although not to the extent of the forever-exalted Robinson, in death as in life Giardello (his career record is 101-25-7, with 33 KO victories) remains an intriguing and, at least in the Philadelphia area, a beloved figure. One of his four sons, Carman, was born with Down Syndrome and, afterward, he tirelessly worked to raise money and awareness for children with special needs. Toward that end, he joined with Sargent and Eunice Shriver to help launch the Special Olympics in 1968. And on May 21, 2011, a life-sized statue of Giardello – who was 78 when he took his eternal 10-count on Sept. 4, 2008, the result of congestive heart failure and complications from diabetes — was unveiled in the South Philly neighborhood in which he was viewed as a hero for reasons that extended beyond his ring prowess.

“Every now and then, somebody comes along who shows what can happen in a lifetime,” the statue’s creator, sculptor Carl LeVotch, said prior to the unveiling. “Joey Giardello is one of those guys. I saw Joey not only as a terrific fighter, but as a father who cared deeply for his disabled son.”

READ THE LATEST ISSUE OF THE RING FOR FREE VIA THE NEW APP NOW. SUBSCRIBE NOW TO ACCESS MORE THAN 10 YEARS OF BACK ISSUES.