The Ring remembers Canadian featherweight contender Art Hafey, who faced three Hall of Famers

“I felt like I was exploited. I fought my way to the No. 1 position, but they wouldn’t acknowledge it while I was ready. I was No. 1 in the world and fighter of the year in California in 1975, and in 1976 it was over.”

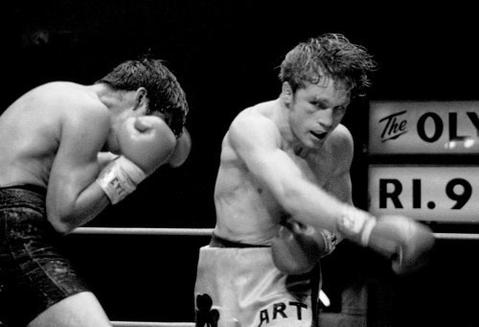

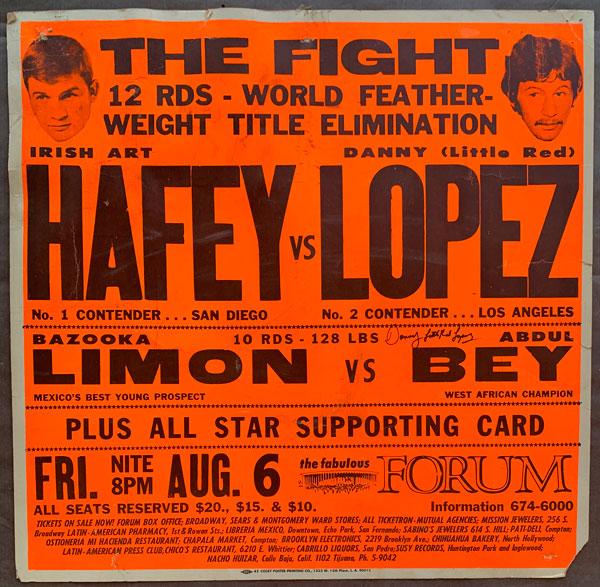

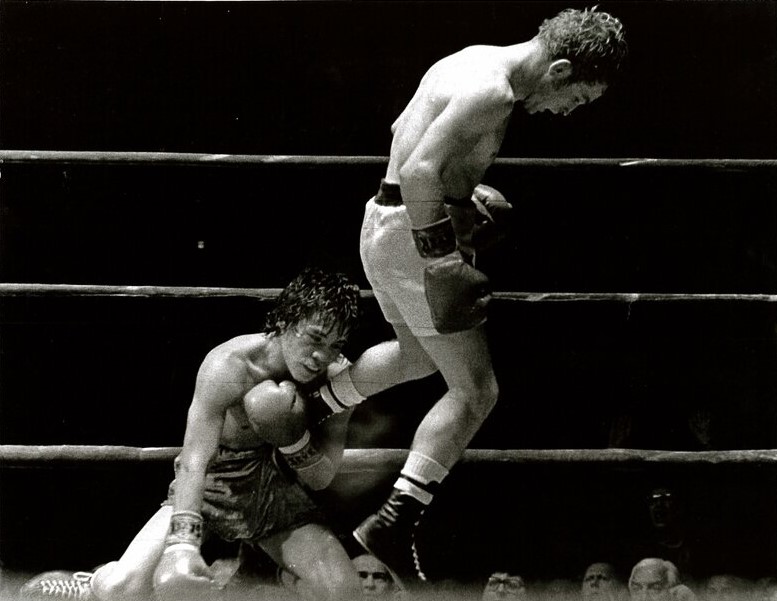

In the final bout of “Irish” Art Hafey’s career, soon-to-be featherweight champion Danny “Little Red” Lopez stopped him in the seventh round. In attempting to overcome a massive height and reach disadvantage, Hafey absorbed inordinate punishment from the hard-hitting Lopez. Although Hafey proved just how tough he was, the referee was wise to stop it when he did.

But if you ask Hafey, it wasn’t the Lopez fight that ruined his career. That came when he obliterated Rodolfo Moreno with a picture-perfect left hook in March 1976. Even though that fight ended the way he wanted, it didn’t go as planned.

“I sustained a brain hemorrhage in that fight,” details Hafey. “The fight shouldn’t have gone more than four or five rounds, but it ended up going almost 10 rounds, and during those rounds, I sustained that injury. And I’ve had side effects ever since. When I look straight ahead, I have a significant area of impaired vision. I used to walk in front of cars because of the blind area.”

Leading up to the Moreno fight, Hafey couldn’t have had a better year. In 1975, he won all 11 of his fights and, as a result, became the No. 1 featherweight contender. But sadly, that would be the closest he would ever get to a world title; he never received the opportunity to fight for the belt.

But although he never became champion, Hafey’s career is deserving of praise and recognition. That recognition arrived in the form of induction into the West Coast Boxing Hall of Fame as part of the 2020 class, including Oscar De La Hoya, Ceferino Garcia, Michael Nunn, and the Ring’s own Doug Fischer, to name a few.

But although he never became champion, Hafey’s career is deserving of praise and recognition. That recognition arrived in the form of induction into the West Coast Boxing Hall of Fame as part of the 2020 class, including Oscar De La Hoya, Ceferino Garcia, Michael Nunn, and the Ring’s own Doug Fischer, to name a few.

Hailing from Nova Scotia, Canada, the same province that produced George Dixon and Sam Langford, Hafey first learned to box along with his older brother at a local club. “My dad always enjoyed the sport and got my brother Lawrence and me started when I was 12,” recalls Hafey. “We were taught by Donnie MacIsaac at the Archie Moore Boxing Club in Trenton, Nova Scotia.”

After roughly 40 bouts as an amateur, Hafey turned pro in 1968, and most of his early fights were in Nova Scotia or Quebec. After his 23rd professional bout, he made a move to California to give himself the best chance to achieve his championship aspirations.

“I wanted to get somewhere in the sport, so after the Tommy Grant fight, my manager Al Bachman hooked me up with a great old guy in Suey Welch down in San Diego,” says Hafey. “Bachman was once the manager of Burke Emery, who would later become my trainer. It was quite a move, and I learned so much in a short time.”

Once Hafey relocated to California, he kept up a blistering schedule, winning 13 of 14 fights in less than a year before getting a significant opportunity against Ruben Olivares in Monterrey, Mexico. In the most notable performance of his career, Hafey knocked out Olivares in the fifth round.

Hafey, also known as the “Toy Tiger”, would follow that up with five more wins before agreeing to rematch Olivares at the Forum in Inglewood, California. To his credit, Olivares boxed an intelligent fight in the sequel. Despite his affinity for trench warfare, Olivares stayed disciplined and used lateral movement and a committed jab to keep Hafey at the end of his punches and earn a split decision win in the process. While Hafey had his moments, including a knockdown of “El Puas” in the 10th, he didn’t cut the ring off effectively and couldn’t stay on the inside long enough to win rounds.

Although Hafey lost the rematch, he has the utmost respect for his Mexican rival. “The rematch was quite different; he avoided me so much in that second fight. No disrespect to Olivares because he was probably the greatest bantamweight of all time,” credits Hafey. “But the thing is, I always acknowledge the fact that I didn’t beat him at his best because when we fought, it was at featherweight, so he lost some of his power. He was such a great fighter; I don’t like to diminish his greatness.”

Two months later, Hafey faced another ring legend in his home country. Although getting stopped in five rounds by a pre-championship version of Alexis Arguello is nothing to be ashamed of, there would be cause for more heartbreak soon after that. Less than a year after Hafey beat Salvador Torres, it was Torres who received a title shot against Arguello. Unfortunately for Hafey, that was quintessential boxing politics shafting a deserving fighter once more.

Two months later, Hafey faced another ring legend in his home country. Although getting stopped in five rounds by a pre-championship version of Alexis Arguello is nothing to be ashamed of, there would be cause for more heartbreak soon after that. Less than a year after Hafey beat Salvador Torres, it was Torres who received a title shot against Arguello. Unfortunately for Hafey, that was quintessential boxing politics shafting a deserving fighter once more.

Speaking to Hafey, you can hear the disappointment in his voice when he talks about his career. “There are many things that I am proud of, but it’s hard to be proud when my career ended abruptly, and I didn’t get to enjoy being that highly rated because it was all over so quickly. It’s really frustrating.”

Part of his frustration stems from the issues he had with his trainer-turned-manager Burke Emery. Hafey acknowledges the vital role that Emery played in his development as a fighter, but Emery’s skills as a manager paled in comparison.

“I have to acknowledge Burke Emery, who was the man who developed my style. The Rocky Marciano style. That’s how he trained me because I was short; he taught me how to body punch,” says Hafey. “He always said, ‘kill the body, and the head will die.’ That’s to whom I attribute my success. But although Emery was a good trainer, he couldn’t manage even though he thought he could; he didn’t have the business knowledge.”

But Hafey isn’t just upset with how Emery managed his career. He also places blame on the referee and ringside physician on duty during his fight with Moreno when he suffered his life-altering brain injury.

“There is no fighter who took better care of himself than I, and I ended up having a brain hemorrhage. If you see the fight, any ringside physician would’ve stopped that fight, but they didn’t protect me,” proclaims Hafey. “You see anybody with a badly swollen head, and you’re going to rush them to the hospital. They didn’t even give me an icepack after the fight. If I had been thinking clearly, I would have tried to sue them for not protecting the athlete. They should have stopped it immediately, but they didn’t do it for me and that changed my life forever.”

Despite the disappointing coda to Hafey’s career, he was able to find meaning in his life after boxing. Thankfully he avoided the typical fighter pitfalls of ill-advised comebacks, reckless spending, and destitution.

After being through with fighting, Hafey moved back to Nova Scotia and wisely invested in a real estate property, using his career-high $25,000 paycheck from the Lopez fight to do so. But more important than providing revenue, that property enabled him to meet his long-time wife, Cathy. “It’s been generating a lot of good income for many years, and it’s how I met my wife, so it’s the best investment I ever made; it’s still paying big dividends.”

When it comes to his career, it is clear that Hafey has regrets for how he was managed, and one can only feel that he deserved more from the sport to which he dedicated his life. And while he never became champion, he did share the ring with three Hall-of-Famers and wasn’t an easy out for any of them. Unfortunately, he still has to live with the side effects of injuries he sustained during his career, which only lends more credence to the fact that no fighter truly leaves this sport fully intact.

SUBSCRIBE NOW (CLICK HERE - JUST $1.99 PER MONTH) TO READ THE LATEST ISSUE