Perception of Muhammad Ali shifted after cruel battering of Ernie Terrell

Anyone who has ever watched a National Geographic wildlife documentary understands that nature is necessarily savage in the animal kingdom. But it is not always maliciously so. In the constant struggle among predators and their intended prey, those that kill almost always do so to feed themselves or their young, and their would-be sources of sustenance flee or fight back in a desperate attempt to survive. Only the planet’s highest life form, humans, intentionally inflict pain, or worse, for such esoteric motives as revenge, pride, profit or gratification of ego.

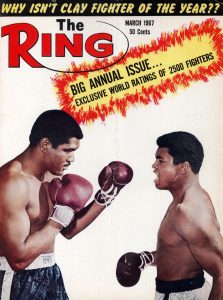

Ali and Terrell on the cover of Ring Magazine.

Well, that assessment might not be absolutely correct. A recent incident in my home, and the upcoming 55th anniversary of the Muhammad Ali-Ernie Terrell heavyweight unification bout in Houston’s Astrodome (which occurred on February 6, 1967), reminded me that there are possible exceptions involving actions that presumably separate man from beast.

In the process of having a new back door installed, some outdoor mice took advantage of the opening to scurry inside, obliging us to purchase sticky traps in order to capture and dispose of the little critters. One ambitious but ultimately unfortunate mouse, however, somehow made its way to the third floor, where my wife’s and my bedroom, my office, the master bathroom and two attics are located, and wound up in the jaws of our pet cat Kiki. For a time, Kiki eluded our attempts to corner her even as she appeared to be toying with the still-alive but no-doubt-petrified rodent. Kiki finally stopped darting about and reluctantly yielded her prize after she had completed the fatal task.

Turns out Kiki’s intentional abuse of the mouse was reflective of a basic instinct that is prevalent in all cats. An article by wildlife rehabilitator Logan Forbes indicates that “the animal most associated with this behavior is the domestic cat. They appear to torture or toy with their prey for their own entertainment, dragging out their victim’s suffering, before the inevitable conclusion … All cats, big and small, treat their prey similarly. That is the way of the cat.”

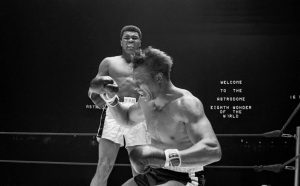

Ali floors Cleveland Williams. Photo credit: Bettmann/ Getty Images

Interestingly, Ali’s most recent defense of his WBC championship prior to his matchup with WBA titlist Terrell was against Cleveland “Big Cat” Williams on November 14, 1966. On that night, during which he appeared to be at the height of his athletic gifts, Ali was like a ravenous lion and the 33-year-old, once-formidable Williams more akin to a stricken wildebeest. Ali’s hands were a blur as he tattooed his no-chance opponent with every weapon in his arsenal, stopping him in three one-sided and thoroughly efficient rounds. Although CompuBox had yet to be founded as a statistical tracker of punches, Bob Canobbio and Lee Groves, in their book Muhammad Ali: By the Numbers, studied the video of the mismatch and determined that Ali landed 46 of 74 power shots (62.2%) overall and an even more incredible 22 of 31 (71%) during the put-away round.

Fortunately for Williams, Ali took care of business in a jiffy, sparing the designated victim 12 additional rounds of sustained malevolence. Then again, Ali – in his eighth defense under his second new name (he briefly went by Cassius X, but never fought as such), having renounced his birth name of Cassius Marcellus Clay two days after he had wrested the title from Sonny Liston, who quit on his stool after six rounds on February 25, 1964, regarded Williams as just another guy to be beaten up. Terrell, however, was a different matter. The Chicagoan refused to refer to Ali by his preferred Muslim name, and by continually identifying him as “Clay” that incited a deep-seated desire in Ali to subject the blasphemer to as much discomfort as could be distributed over the full 15-round distance.

Terrell, however, was hardly the only notable boxing figure who declined to accept the now-former Cassius Clay as Muhammad Ali. A similarly cruel and intentionally prolonged beatdown of two-time former champ Floyd Patterson was administered by Ali on November 23, 1965, in Las Vegas, and for the same reason: Patterson’s adamant refusal to acknowledge Ali’s name of choice.

“I want to win back the title because I wouldn’t just be taking it from him, I would be taking it away from a group of people, from the Muslims, and giving it back to America,” Patterson had said in the lead-up to the fight that was more injurious to his health and well-being than had been his two one-round knockout losses to Sonny Liston. Those thrashings, as emphatic as they were, at least had been administered swiftly.

Given the political and social upheaval of the era, much as is the case now, America was cleaved into two separate and distinct camps, the subset of sports being no exception. Two of the United States’ most influential sports columnists, Red Smith of the New York Times and Dick Young of the New York Daily News, couldn’t have made their antagonistic feelings toward the man they still exclusively or mostly called Cassius Clay had they owned pieces of Floyd’s contract.

Dick Young was part of the old guard of American sportswriters threatened by Ali’s bold and unfamiliar personality and identity.

Young wrote that Patterson’s comments were the proclamation of “the holy war against Muhammad Ali and all of Black Islam, who for more than two years have held Nat Fleischer’s holy trophy captive in some dark mosque,” He further noted that the fight was “not merely Patterson against Clay. It is Christian against Black Muslim. It’s good guy against bad guy. It is David against Goliath.”

Smith, apparently not believing what his eyes had already seen of Ali and of Patterson inside the ropes, picked Floyd – who reduced his already slim chances of pulling off an upset by concealing the fact he had injured his lower back in training – to win in seven rounds because “Cassius Clay hasn’t beaten anybody yet.”

That Patterson was stopped in 12 rounds instead of hanging on long enough to lose by Grand Canyonesque margins on the scorecards was not so much a slip-up by Ali as it was due to the compassion of referee Harold Kessler, who decided he had seen enough of the one-way brutalization. Wrote Smith: “Foolishly concealing a sacroiliac condition, Patterson made his way into the ring with an old man’s tread and, for most of an hour, tried unsuccessfully to defend himself from cruel blows intended to flog him to the edge of endurance but not beyond. With a chilling display of malice, Ali purposefully prolonged the torture into the 12th round to punish Patterson for daring to call him Cassius Clay.”

To his credit, Ali, or by whichever name his supporters or detractors sought to call him, was a very active champion, logging an incredible (by 21st century standards) five defenses in 1966, with victories over George Chuvalo, Henry Cooper, Brian London, Karl Mildenberger and Williams, all of whom were sensible enough to not overly tweak the future “Greatest of All Time’s” nose with inflammatory remarks about the champion’s name or religion. But then came 1967, with Terrell not disposed to paying the ring king proper homage.

Ali vowed to punish Terrell as he did Floyd Patterson in a previous title defense.

Rising to the bait, Ali vowed he would give Terrell “a Floyd Patterson humiliation beating,” which had the same negative effect on a new set of recalcitrant newspapermen that his earlier comments about Floyd had. The Boston Globe’s Bud Collins’ listed the champ as “Cassius Muhammad Ali Clay” in print and referred to him as “America’s leading draft dodger.” And this, from the Philadelphia Inquirer’s Gene Courtney, who described Terrell as “A man of simple tastes and quiet dignity” and “Clay” as “the world most celebrated camel driver” whose verbal patter was “idiotic” and “unpatriotic.”

As a surprisingly narrow 1-to-4 favorite, and with a massive live turnout of 37,231 spectators in the Astrodome, Ali – clearly enjoying his role as a vengeance-obsessed cat to Terrell’s 6-foot-6, 212½-pound mouse –dispensed pain in measured doses, bit by bit transforming the courageous but outclassed Ernie’s face into an ugly montage of cuts, lumps and bruises. Ali appeared on the verge of closing the show in the seventh round, during which he had Terrell nearly out on his feet, but he instead elected to not press his advantage in the eighth, substituting shouted demands of “What’s my name?” in place of punches that would have had the effect of putting the object of his scorn out of his misery. And so the parade of physical and psychological abuse continued to the final bell, with the referee, an assignment that again went to Kessler, declining to step in and give Terrell the deservedly early exit he had provided for Patterson.

Perhaps not surprisingly, some key members of the on-hand press contingent still refused to give the 25-year-old Ali undiluted recognition as a fighter with the stamp of impending, if not already achieved, historic greatness. Wrote Arthur Daley, of the New York Times: “Clay did everything to Terrell but knock him out. It was a magnificent exhibition of boxing skill at its very best, but the champion’s ability to hit with power is still suspect. Although Joe Louis admitted afterward that he now was willing to concede Cassius was a great fighter, it’s a cinch the Bomber never would have let the battered and helpless Ernie escape.

Ali attacks the defense-focused Terrell.

“Maybe it was Clay’s own fault. He had Terrell wobbling and in distress in the seventh round, but he turned propagandist in the eighth and blew his chance. That’s when he taunted his gallant opponent, expounding one facet of his doctrine of racist hate instead of attending to the business at hand.

“If he had shut his big mouth and delivered the message with his fists, he might have gotten it across better. All he did was put steel in Terrell’s determination to spite his tormentor by surviving in a vertical position to the end. Ernie had so much courage and dignity in defeat that he gained a lot of respect and admiration from the ringsiders. About all that Clay achieved was to keep destroying the image he once had of being the likable charm boy. He showed himself to be a mean and malicious man.”

More than a half-century later, the narrative has dramatically changed. By and by Ali’s rhetoric became less confrontational and polarizing, which contributed in no small part to a more sympathetic and accepting public perception of him. So, too, did the fact that he was a still-excellent but less-dominant fighter after his 43-month forced exile from boxing at the height of his career for his refusal, on religious principle, to be inducted into the U.S. Army during the Vietnam War. The post-layoff Ali – ironically, like Terrell – demonstrated he also could take copious amounts of punishment as well as dish it out (see the holy trilogy with Joe Frazier and the shocking KO of George Foreman in Africa), that seemingly bottomless well of courage bringing him more acolytes, even from the ranks of those who once had pilloried him. He remained a devout Muslim to the time of his death, at 74, on June 3, 2016, following a 30-year battle with Parkinson’s syndrome that sapped his physical vitality if not his spirit, and his sense of loyalty was such that he refused to part company with the non-black members of his retinue, chief among them trainer Angelo Dundee, business manager Gene Kilroy and personal physician Dr. Ferdie Pacheco.

As if all that weren’t enough, he was presented with the Presidential Citizens Medal by President George W. Bush on January 25, 2005, and the Liberty Medal in Philadelphia, in celebration of the 225th anniversary of the U.S. Constitution, on Sept. 13, 2012. He undertook missions to developing countries to deliver food and medical supplies, in addition to serving as a fundraiser for Special Olympics and the Muhammad Ali Parkinson Research Center in Phoenix. He was voted “Sportsman of the 20th Century” by Sports Illustrated and “Sports Personality of the 20th Century” by the British Broadcasting Company He even helped facilitate the freeing of 15 Americans and two Canadians during a face-to-face meeting with Iraq’s brutal dictator, Saadam Hussein, in Baghdad in 1990.

When Ali took his leave from this earth, in some ways he was better than he had been as a young firebrand, perhaps less so in some other ways. But in whichever stage of a life he happened to be in during an ongoing metamorphosis of self-discovery, he for certain remained one thing:

A cat beyond replication.