Fighting Words: Anthony Joshua can’t delay Tyson Fury fight (even if he should)

Ready or not, Anthony Joshua must fight Tyson Fury in 2021.

That readiness remains in question — even after his one-sided performance against Kubrat Pulev last Saturday in London. Joshua was never in danger, scored four knockdowns and finished Pulev with a huge right hand in the ninth round.

Joshua’s victory over Pulev was an important step forward, putting last year’s shocking technical knockout loss to Andy Ruiz farther behind him. There were further additions to the work that began before the Ruiz rematch in late 2019, when his team essentially rebuilt from the ground up, setting up the most basic foundation after a fighter who’d once been ready to rumble was rendered into rubble.

This isn’t the overconfident champion who wound up concussed and confused, uncertain why he felt this unfamiliar way, dropped four times and defeated for the first time as a pro.

This also isn’t the overly cautious challenger who returned six months later, boxing tentatively but technically, working almost exclusively behind his jab to keep away, keep safe, keep what happened before from happening again.

This Anthony Joshua was poised and patient, composed and confident in his game plan and his ability to make it succeed. He retained his three major world titles and revived the conversation about a big fight with the big man who holds the fourth.

Fury.

They’ve been on a collision course for nearly five years. Fury won the lineal heavyweight championship and three world titles from Wladimir Klitschko at the end of 2015. Joshua, who’d won Olympic gold in 2012, had transitioned from a top prospect into a true contender. When Fury was stripped of one of his belts, Joshua knocked out Charles Martin to win it. Talk turned to pairing the 6-foot-6 titleholder from the London area against the 6-foot-9 champion from Manchester.

It was a big domestic clash at the time, but also a big fight for the heavyweight division. It’s only grown in importance since then. Fury’s time away from the sport allowed Joshua to pick up his remaining titles. He won a battle with Klitschko in 2017 for a second belt in a bout that seemed at the time to be a passing of the torch, and defeated Joseph Parker in 2018 for a third. The last one belonged to Deontay Wilder. Joshua and Wilder weren’t able to reach a deal, however, and Wilder wound up meeting a returning Fury later that year in a dramatic fight that ended with a draw.

There’ve been more heavyweight shockwaves since. Joshua’s loss to Ruiz. The way Ruiz sabotaged himself by showing up in such poor condition for their rematch, allowing Joshua to win with ease. And then the stunning way Fury turned the tables on the powerful Wilder this past February, knocking him down twice and stopping him in seven.

Boxing as a sport is often done in by boxing as a business. Every year includes the frustration of at least one significant match that fails to happen because the fighters can’t agree to it, because the promoters and networks have business interests, because that interest is in protecting their business, and because abstinence is the only guaranteed form of protection. It’s also the least enjoyable.

The time is right for Anthony Joshua to face Tyson Fury, even if the time isn’t exactly right for Joshua himself. It is the natural next progression, even if Joshua is still a work in progress.

As much time has passed since the Ruiz fights, it’s still only been 18 months since the initial loss, 12 months since the rematch win. As good as Joshua looked against a decent challenger in Pulev, there’s still a gulf of talent between Pulev and other fighters who have more dimensions, more hand speed, more power, more ability, more everything.

The majority of work to improve Joshua comes in his training camps, accentuating his strengths, healing or otherwise hiding his weaknesses, incorporating new techniques and running drill after drill, sparring round after round until these techniques become ingrained in him.

Nothing compares to testing yourself in a real fight.

Wladimir Klitschko had several shaky outings after suffering two humiliating losses to Corrie Sanders in 2003 and Lamon Brewster in 2004. He was hesitant, a fighter who wanted to rebuild but still had an unsteady foundation. He’d gone from thinking of himself as the Big Bad Wolf of the heavyweight division to worrying about his chinny chin chin and wondering whether the next hard blow would bring him tumbling down for good.

Klitschko went down once in a shaky, cut-shortened technical decision over DaVarryl Williamson. He rose three times and looked like a deer in the headlights against Samuel Peter but still fought his way to victory. It took time, repetition, and trial by fire for him to find a surer footing — to trust in his jab, his boxing ability and his footwork to protect him and provide opportunities for heavy right hands to be unleashed. It took more difficult moments and distance outings to show him that his past chin and stamina issues were less likely to plague him again.

There hadn’t been any of these doubts about Anthony Joshua going into the Ruiz fight. They had seemingly been answered already when he went to battle with Dillian Whyte in 2015 and when he got up off the canvas against Klitschko, which so few had been able to do, and recovered to stop him in 2017.

Ruiz turned Anthony Joshua’s exclamation points into question marks. He showed that Joshua could get caught in exchanges, could get hurt if he got caught right, and could get hurt bad enough that he couldn’t recover.

Joshua largely stayed away from exchanging with Pulev on Saturday, though not as dramatically as he’d done in the Ruiz rematch. He was comfortable at mid-range, working first and foremost behind the jab — 195 of his 310 punches were jabs — calmly taking a step back when Pulev approached rather than making a full, panicked retreat. He also tied up when Pulev got too close.

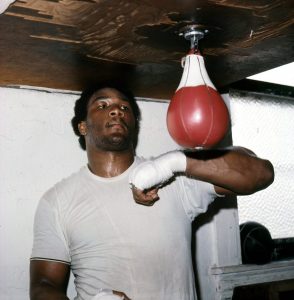

Anthony Joshua exhibited fine form vs. Kubrat Pulev. Photo by Dave Thompson

The jab, in turn, helped set up power shots. It forced Pulev to try to work his way in. Joshua landed a quick counter over Pulev’s jab in Round 1, then wobbled Pulev in Round 3, dodging a jab and returning fire with a hard right hand. Pulev momentarily turned his back to get away, and Joshua went on the attack for the first time, Pulev reeling and turning his back again, ducking his head into the red corner. The fight very well could’ve been over with Pulev unable to defend himself. Instead, the referee ruled it a knockdown and issued Pulev a standing eight count.

Joshua continued his onslaught of power shots, including several right uppercuts, unconcerned about leaving himself open to return fire, as Pulev often hid behind his guard rather than throw back.

That third round was the outlier for the first half of the fight when it came to Joshua’s activity. He went 27 of 62, including 20 of 44 power shots, but soon returned to his more measured work rate, according to CompuBox. He went 6 of 33 in the fourth, 8 of 27 in the fifth, and 6 of 17 in the sixth, most of them jabs, with a total of seven power punches landed across those nine minutes.

Two things can be true: Joshua did the right thing in not trying to put Pulev away in Round 4. And not putting him away further allowed Pulev to recover.

Pulev still couldn’t get to Joshua, not so long as Joshua remained disciplined and stuck to his strategy. Pulev’s approaches were basic enough and slow enough that Joshua had little trouble ducking right hands or backing away from jabs. Joshua barely blinked when Pulev landed a pair of short one-two combinations in Round 5.

Joshua felt comfortable enough in his advantages that he was willing to take more chances, issuing three straight right uppercuts followed immediately by five more power shots from close range in Round 7. And he turned to the uppercut again to bring the fight to an end in Round 9.

If the gap in Pulev’s guard was wide enough to accept Joshua’s jabs, it also remained open for a follow-up right uppercut. Pulev was rocked and tried to tie up. His arms being on Joshua’s shoulders left him open for two more uppercuts, then a left hook and one more uppercut until Pulev dropped. He rose and needed to withstand 18 seconds to make it out of the round. That short amount of time was too long. Two more punches — a jab to set up the big right hand that followed — put Pulev flat on his back. He rolled onto all fours and listened to the referee count him out.

The limited number of fans in attendance at Wembley Arena roared their approval. The post-fight interview quickly turned to a match meant for a much larger audience, for a time when the pandemic is finally over and boxing can return once again to packed crowds and big business.

“Respect to Tyson Fury. He’s a talented guy,” Joshua said. “He’s got loads of fans and he’ll make for a great competition when the time’s ready.”

2021 is the year for Anthony Joshua and Tyson Fury to finally meet. It’s not necessarily as simple as getting Joshua and Fury to agree to a deal, though. And it’s rarely that simple to get two huge stars to agree to a deal anyway.

Fury and Wilder are currently in arbitration, awaiting a ruling as to whether a third fight between the two must come next. Joshua, meanwhile, is waiting to see whether the World Boxing Organization (one of the three titles Joshua owns) will call for him to face mandatory challenger Aleksandr Usyk or will temporarily waive their mandate in favor of a huge event for the undisputed heavyweight championship.

There are upsides and downsides to both scenarios. Joshua would benefit from having more time to prepare for Fury’s power and skill — or for Wilder’s power and speed. But every intervening bout leaves open the possibility of him suffering another upset, flushing the huge payday down the drain.

Joshua and his trainer have rebuilt him by teaching the value of being cautious and judicious, of setting yourself up for success and striking at the right time. This is the right time to take a chance. The risk will be greater, but so will the rewards.

The 10 Count

Berlanga scored his 16th consecutive first-round KO vs. Ulises Sierra. Photo by Mikey Williams/Top Rank Inc via Getty Images

1 – Edgar Berlanga’s run of first-round knockouts — 16 in a row after he dispatched Ulises Sierra on Saturday night — doesn’t matter in the long run. Berlanga hasn’t faced any notable names. He’s a prospect who hasn’t yet proven himself as a contender.

It’s still brilliant marketing. It makes us want to see him fight, even if we see right through what they’re doing.

This much is certain: Berlanga clearly has heavy hands. His past two victims (Lanell Bellows in October, Ulisis Sierra most recently) had never been stopped before. Sierra had lasted the full 10 rounds in his only other loss, going the distance with undefeated prospect Vladimir Shishkin last January. He’d sparred with Sergey Kovalev at four training camps. Berlanga finished Sierra in two minutes and 40 seconds. Only two other Berlanga opponents have lasted longer: one for another two seconds, the other for five.

The 23-year-old is following in the footsteps of Edwin Valero, Tyrone Brunson and Ali Raymi.

Edwin Valero proved to be more than a quickie-KO artist with his savage 130-pound title battle against Vicente Mosquera.

Valero was the real deal, earning 18 straight KO1 entries and soon stepping up to win world titles at 130 and 135. Brunson was more sizzle than steak, reeling off 19 consecutive first-round KOs before Antonio Soriano held him to a draw. Carson Jones burst Brunson’s balloon about a year later.

Ali Raymi was a curiosity as he built up the current record of 20 opening-round KOs in Yemen against a slate of opponents who hadn’t done anything of note before and haven’t done anything of note since. Raymi, who served in the Yemeni military, died in 2015 in the war that continues to ravage the country.

Managers and promoters are supposed to build buzz and get their fighters paid. Mike Tyson’s team fought the young heavyweight often — 19 times in his first 12 months as a pro. They sent compilation tapes of his knockouts to nationally renowned boxing writers. “Whenever possible, Mike’s bouts started at 9 p.m. so that the tape of his latest triumph is ready in time for the nightly newscasts across the nation,” wrote Nigel Collins for The Ring early in Tyson’s career.

Berlanga will either have the goods or he won’t. We’ll enjoy finding out the truth, whatever the truth may be.

2 – Five fights separate Berlanga from the first-round KO record. Imagine if Top Rank decided to set Berlanga up with five guys he could beat in a single night, George Foreman-style.

George Foreman trains in a Los Angeles gym in March 1975. (Photo: The Ring Magazine/Getty Images)

You won’t find those fights on Foreman’s record, however. They were all considered exhibitions, though you wouldn’t know it from the way Foreman approached that night in 1975, about six months after his infamous loss to Muhammad Ali.

“It couldn’t be sold as anything but a non-professional event because of the rules in Ontario. However, it was hardly an exhibition; there was to be no headgear, no large gloves, and the punches were to be authentic,” recounted boxing historian Patrick Connor in an article on FloCombat.com.

Foreman put away each of the first three fighters within two rounds apiece. The remaining two foes each lasted the full nine minutes.

Foreman ended up regretting the venture, he told The Ring in 1976. “That was planned basically for fun. I didn’t realize those five guys wanted a real serious fight,” he said. “I know this brought a lot of criticism, and it was a mistake in judgment on my part. I wouldn’t do it again.”

Boxing’s more accepting of bizarre circuses these days. If we can get a YouTube personality to fight a retired pro basketball player on the undercard of a Mike Tyson-Roy Jones Jr. exhibition pay-per-view with Snoop Dogg on commentary, then we can get Edgar Berlanga beating up a quintet of nobodies live on ESPN.

Sign up fast-food burger chain Five Guys as a sponsor and watch the headlines go wild.

3 – Other notable action this past weekend included Shakur Stevenson looking untouchable against Toka Kahn-Clary, junior lightweight contender Chris Colbert shining against Jaime Arboleda, Masayoshi Nakatani bouncing back from last year’s loss to Teofimo Lopez by getting off the canvas twice and stopping Felix Verdejo, and Matvey Korobov suffering a heartbreaking TKO loss to Ronald Ellis.

Korobov has had a hard-luck career.

Matt Korobov, the definition of a hard-luck fighter.

He was knocked out in a title shot against Andy Lee in 2014. Many felt he was robbed against Jermall Charlo in 2018. Korobov was announced as the winner of a 2019 bout against Immanuwel Aleem, only to learn in his dressing room that the commission had tabulated the scores wrong and the result was actually a draw. Later that year, Korobov fought Chris Eubank Jr. but hurt his shoulder just three and a half minutes in and couldn’t go on.

Korobov’s body betrayed him again on Saturday on the Colbert-Arboleda undercard.

He faced Ronald Ellis, who’d bested Aleem late last year. Ellis came in five pounds over the 161-pound limit. Korobov fought anyway, needing this match and a victory in order to keep open the possibility of another substantial opportunity. He was ahead on the scorecards when he suffered an injury to his Achilles tendon at the end of the Round 4.

Korobov is nearly 38. His body is seemingly sending him a message, even if he’s otherwise still capable in the ring. Every training camp will only add more wear and tear. No one wants to go out this way, but this is better than coming back, suffering another injury in the middle of a match, trying to fight on and getting hurt even worse.

4 – “Sergio Martinez-Felix Sturm a possibility, says promoter”

That article could’ve been from 2010, when Martinez was the lineal middleweight champion while Sturm held a title belt at 160 pounds.

Instead it was from this very website in 2014, after Martinez had just lost his championship to Miguel Cotto and was suffering from a bum leg that would soon force him to retire. Sturm, meanwhile, had recently been defeated by Sam Soliman.

That headline could be reused again now. No, really.

Martinez, now 45 years old, came back earlier this year in Spain after six years away from the ring, knocking out some dude named Jose Fandino in seven rounds. He’s scheduled to fight again this Saturday, taking on some other dude named Jussi Koivula, who was last seen at welterweight getting blown out in two rounds by prospect Conor Benn.

Sturm is also fighting this Saturday in Germany, returning for the first time in nearly five years. He’d tested positive for a banned substance after his last fight and has dealt with legal trouble over tax evasion charges in the time since. The 41-year-old will face an unbeaten dude named Timo Rost, who is 10-0-2.

There’s been no talk of pitting the former titleholders together — no talk except from sick minds like mine.

5 – Somewhere, there’s an alternate universe where Felix Sturm was awarded the decision many thought he deserved over Oscar De La Hoya in 2004.

Yes, we’re allowed to print that sentence on this website.

6 – It’s been nearly five years since the much-maligned World Boxing Association said it would work to reduce the number of world titles it awards — or rather the number of secondary, tertiary, and, yes, even quaternary baubles it recognizes. (The situation is so bad that I had to look up the words to describe it!)

These belts exist mainly to siphon more cash away from fighters who are sold a bill of goods, believing that these otherwise meaningless belts are a sign of accomplishment and could earn them a real title shot someday.

“I am working to reduce the titles,” WBA head Gilberto Mendoza Jr. told boxing writer Dan Rafael in January 2016. “At first some promoters [might] complain. I just tell them it is my final decision. They would have to live with it.”

It’s… not going well.

In 2015, the WBA had 42 titleholders among the 17 divisions in men’s boxing. By December 2016, there were 33, plus a vacant heavyweight title, meaning there were still an average of two titles per division — and some weight classes still had three.

Now? There are 39. We’re somehow getting worse instead of better. That count includes “super” titleholders in 16 of the 17 weight classes. It includes 15 “world” titleholders, which we boxing fans tend to refer to as the “regular” title when there’s also a “super” titleholder. Somehow, even with all these super and world titleholders, there’s a need for another eight “interim” titleholders.

And that count doesn’t even include something called the “WBA Gold Champion.” Why is this a thing? There are another 11 fighters with those, bless their hearts. That makes 50 belts in 17 divisions, an average of three per division.

(For the sake of our sanity, we’ll ignore the various international, intercontinental — lord knows what the difference between those two is — and regional belts.)

7 – Here’s Mendoza defending the situation earlier this year to ESPN’s Salvador Rodriguez, with approximate translation via Google and BoxingScene:

“They tell me that there should only be one champion, but they don’t give me solid arguments. They tell me that they [the titles] are devalued, but when we talk about having a tournament to leave only one champion, not everyone wants to enter. When we talk about accepting a champion vs. champion fight, not everyone is willing.”

Of course, the titles aren’t devalued literally when the WBA charges promoters $6,000 to $25,000 (depending on the division and the fighters’ combined purses) to stage a super, regular or interim title fight. A “gold title” fight will always cost a promoter $25,000.

The WBA charges the fighters between $1,500 and $250,000 in sanctioning fees for super, regular, interim and gold title fights. Those prices don’t include the cost of the belts themselves, which range from $2,500 to $5,000.

Now multiply those numbers by 50.

Figuratively, however, this situation does indeed water down the titles. It’s hard to build up a sport when casual fans are confused as to who actually matters. It’s bad enough that there are four sanctioning bodies. But when a single sanctioning body has four titles?

Then again, Mendoza did make a good point here:

“On the other hand, a boxer with a title does better, a boxer who goes to a title fight does better, a network that broadcasts a title fight does better, a promoter who has a title fight does better. The same fan [who complains], if he knows there is a title at stake, they are more attentive [to the fight].”

The reality, though, is this situation is easier to fix than Mendoza lets on. The number of titles would’ve dwindled by now the WBA had merely stopped awarding them after announcing the cutback. These “title fights” didn’t appear out of thin air. Don’t hold your breath for things to get better in the near future, if ever. In this sport, profit will always trump principles.

8 – Here’s an actual ESPN news alert from last month, when the upcoming 168-pound championship fight was made official:

“Canelo Alvarez will return to the ring, fighting Callum Smith on Dec. 19 to unify the WBA super middleweight titles.”

Boxing writer Matt Richardson chimed in with this apt, cutting remark: “I’m so old I remember a time when unification meant unifying belts from other sanctioning bodies.”

Only in boxing could you have a four-man tournament to unify one world title. The WBA is like the Voltron of Boxing.

9 – This has been a year where some real dudes have stepped up and taken on tough challenges in their first fight back after long layoffs. While others opted to shake off rust — an understandable choice — we got Teofimo Lopez jumping straight in with Vasiliy Lomachenko, Errol Spence coming back from that horrific car crash and defending against Danny Garcia, and now Canelo Alvarez back in the ring against Callum Smith.

Both Alvarez and Smith deserve credit for making this fight after about 13 months away. Smith is The Ring’s super middleweight champion, recognition he earned after winning the World Boxing Super Series tournament in 2018 with a seventh-round knockout of George Groves. He’s not an easy out whatsoever, not even for a pound-for-pound king like Alvarez.

THE FIRST FACE OFF 👀@Canelo vs @CallumSmith23 🔥

👑 WBA Super

👑 Ring Magazine

👑 WBCWorld Super-Middleweight Titles on the line this Saturday! @DAZNBoxing #CaneloSmith pic.twitter.com/GyfF1E4Ynz

— Matchroom Boxing (@MatchroomBoxing) December 15, 2020

That’s par for the course for Canelo, who’s gamely taken on some tough challenges over the years, whether it’s facing Floyd Mayweather Jr. as a 23-year-old, defending against the likes of Erislandy Lara when so many avoided the skilled Cuban boxer, and facing off with Gennady Golovkin twice.

There were plenty of easier opponents each man could’ve picked. In an era when we expend so much oxygen and energy explaining why this fight can’t be made or debating who’s to blame for a fight not happening, we’re getting The Ring’s 168-pound champion against The Ring’s 160-pound champion.

10 – Alvarez has expanded his business ventures beyond boxing, launching the CaneloPhone, which offers prepaid service at three different tiers: the “Super Welter Plan,” the “Middle Weight Plan” and the “Light Heavy Weight Plan.”

Not mentioned on the CaneloPhone website? The DAZN Plan. The annual plan costs $70 million, it only makes two calls each year, and it eventually stops calling anyone you’d prefer for it to call…

Follow David Greisman on Twitter @FightingWords2. His book, “Fighting Words: The Heart and Heartbreak of Boxing,” is available on Amazon.