Hector Camacho’s unique story hardly could be condensed into a mere 90 minutes

Given my dealings with the late Hector “Macho” Camacho over the course of the years our professional lives intersected, I was one of many reasonably logical choices Ring Magazine’s Editor-In-Chief Douglass Fischer could have made to do the review of Macho: The Hector Camacho Story, a 90-minute documentary about the flamboyant three-division world champion that premieres Friday, December 4, on Showtime. It was an assignment I had no hesitation in accepting, given the myriad highs, lows and in-betweens of a unique character separate and apart even from other fighters who arose from similar circumstances to blaze distinctive trails to glory, perdition or both.

Not that any headline ever fully encapsulates the subject matter that follows, but the one I might have chosen for this treatise on the onetime (and, perhaps, still) pride of New York City’s Spanish Harlem had already been used. The Most Unforgettable Character I’ve Met, by Alex Haley, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning 1976 novel Roots: The Saga of an American Family, appeared in the March 1961 issue of Reader’s Digest and told the story of Malcolm X. Was the “Macho Man” the most unforgettable character I’ve ever encountered in boxing? Well, maybe, and maybe not. But if he doesn’t claim the No. 1 slot in my pound-for-pound list of memorable practitioners of the pugilistic arts, he at least is hovering somewhere near the top.

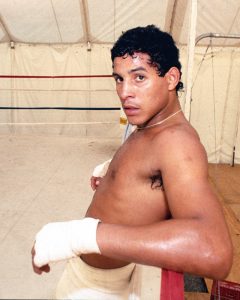

Hector Camacho takes a break during a training session in a tent on the grounds of the Canyon Hotel, Palm Springs, California, May 9, 1983. Photo by Bob Riha, Jr./Getty Images

By alternating turns, Camacho was, depending on the prevailing perception of him at any given moment, a hero, a villain, an inspirational figure, a clownish caricature, an arrogant egomaniac, an emotionally fragile bundle of secret fears, a devoted family man and someone who periodically cast aside longtime friends in favor of newcomers to his retinue who sought to take advantage of him. If there is a unifying thread that ties together the native Puerto Rican’s many sides, it is this: he not only couldn’t surmount his addiction to drugs and alcohol, he scarcely bothered to try.

On the cusp of middle age and already retired from the sport that made him occasionally rich and indisputably famous, Camacho, with the aid of some steadfast buddies who hoped to see him shine once again in the sport he had so indelibly marked with his skill and outsized personality, attempted to whip himself into shape for another seven-figure bout. “Midway through this, he comes in and says, `I got to talk to you,’” Rudy Gonzalez says toward the end of the documentary. “I said, `What’s up, Champ?’ He goes, `I can’t do this fight. I appreciate what you guys are doing, but I just want to get high … I am a champion, but I’m a junkie first.

“He was broken. When I looked into his eyes, I realized then there was nothing left.”

And this, from Camacho’s first wife and love of his life, Amy Torres Camacho, who finally reached a point where even she had nothing left to give that might serve to again prop up the husband she said that, despite his flaws, “I knew deep inside was this great, awesome person.”

“Macho did what he wanted, how he wanted, when he wanted,” she said. “I was actually his enabler for a very long time. What I thought was good and helping him and protecting him was actually helping him do what he was doing, and get away with it …

“I didn’t know any better. Once I grew up, I realized it just wasn’t for me to be in that environment. I can’t have these kids (three sons) around this craziness.

“I stood by his side and I had his back. But I knew Macho was never going to stop doing what he was doing because he readily said, `I like it, I love it, you met me like this and I’m going to stay like this.’ He was running away from love, he was running away from family. He was always running away because everything for him was the street. He didn’t want to give it up.”

Perhaps ironically, in rejecting Hector’s desperate request to reconcile, re-marry and start fresh, Amy told him, “How about when you’re 50, we’ll meet up again, we’ll talk and see where we’re at. Maybe then we can raise the grandkids.”

That pipe dream basically ended in a hail of bullets on November 20, 2012, as Camacho sat in a parked car in his birth city of Bayamon, Puerto Rico, alongside a childhood friend, Adrian Mojica Moreno, better known by his street name, “Jamil,” a reputed pimp and drug dealer. Jamil died there and then, his body riddled with slugs, but Camacho would linger in a hospital, brain-dead for four days after he took a bullet in his lower jaw that clipped his spine, took a right turn and sliced his carotid artery. Two days after the shooting that was witnessed by dozens of bystanders, his mother, Maria Matias Camacho, signed a release to remove her son from life support.

Felix Trinidad speaks during Camacho’s funeral at the Department of Recreation and Sports on November 27, 2012 in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Photo by Dennis M. Rivera Pichardo/LatinContent via Getty Images

On episodic television, in which fictional perpetrators of crime, especially murder, are almost always brought to justice by the time the final credits roll, the ending to the Showtime documentary would have shown a grieving Maria having the satisfaction of knowing who it was who pulled the trigger that removed any lingering hope that her son would find his way back onto the right path he so frequently had wandered from. But no; as executive producer and narrator Eric Drath reveals of his own efforts to find some sort of closure for Camacho’s family members and many admirers, “the truth is, it’s anything but uncommon for a murder to remain unsolved in Puerto Rico. Even though it’s a territory, it has the second largest police force in the United States, second only to New York City. Just 23 percent of crimes committed on the island are ever solved.”

Standing at the site where his father was gunned down, Hector Jr., who also went on to be a boxer of some note, despairs that the crime that touched so many will ever be solved. “I wanted to see the place where he got shot,” the Macho Man’s namesake said. “It doesn’t add up right, it doesn’t seem right. It gives you more questions. This is a busy neighborhood. It’s one of the main streets in Bayamon. And nobody knows nothing, nobody seen nothing. Unbelievable.”

But Macho: The Hector Camacho Story, while addressing the tragic aspects of a life that careened up and down like an amusement park roller-coaster, crams as much of the positive stuff into its 90 minutes as is possible, although there is a lot more that might have been included. I was a bit surprised that there was no reference to Patrick Flannery, for 31 years an employee of the New York City public school system, who first met Camacho when he was a 15-year-old problem student whose class attendance was spotty and his adherence to established rules even more so. Flannery became an adviser of sorts to the wild child, making for a long-term relationship that became something of a running comedy routine.

Flannery loved to tell the tale of how Camacho, who preferred to sleep in the nude, awoke late one night in his hotel suite the night before he was to fight, ready to boogie. But Flannery had hidden all of Camacho’s clothes, in the hope that the missing threads would somehow persuade the fighter to remain in bed and get his rest. “He went out stark naked in the hall,” Flannery told me and other reporters. “He went all the way to the elevator before I caught up with him and threw him a pair of pants.”

That incident no doubt would have been a highlight of the documentary had tape been available, but Camacho’s proclivity for nocturnal adventure, frantically fueled by his craving for illegal substances, is examined at length nonetheless.

“When Camacho became an overnight sensation, he became a serious partier,” Gonzalez noted. “The excitement of winning, the people … there was never running out of anything. So how much can we consume? How much partying can we do? How much drinking can we do? The next thing you know, he’s on a course two or three weeks later, no food, no sleep and we can’t bring him down.

“You can have everything in the world and still have nothing. Money does not make you happy. It only buys you time to realize you’re not happy. And when a demon lives within you, he doesn’t leave.”

The demon within him, if you discount his penchant for getting into frequent scraps, emerged gradually, eventually obfuscating the giddy kid with the nimble feet and quick hands who was so good-natured in his prank-pulling, even the occasional car theft, that it was difficult for anyone to stay mad at him for long. “He was always in fights,” said one of his early acquaintances. “Street fights. Alley fights. School fights. Family fights. Just fight to be fighting, that’s all. It’s in him.”

The promise of Hector Camacho first became evident in the New York Golden Gloves, where he impressed knowledgeable observers not easily inclined to predict future stardom. Randy Gordon and Steve Farhood, both of whom served as editors of The Ring, sensed that the effervescent southpaw did indeed possess a gift that would take him far.

“I saw this kid, this speedy little kid, and I’m like, `Oh, my God, who is this?’” Gordon says in the documentary. “And the more he fought, the more I fell in love with him.”

Added Farhood: “His hand speed was fantastic. So right away I sensed that this was a special kid. There was something about Camacho that made you look at him. And it wasn’t just the flash. It was the boxing ability, too.”

The then-21-year-old Camacho was 21-0 with 11 KOs when he got his first shot at a world championship, against highly regarded Mexican Rafael “Bazooka” Limon, on August 7, 1983 in San Juan, Puerto Rico. And when he stopped Limon in five rounds to claim the vacant WBC 130-pound belt, he became an even bigger celebrity and role model to his fans both in his homeland and in Spanish Harlem, the epicenter of Puerto Rican culture in New York to which the four-year-old toddler, his older sister Raquel and mom had emigrated in 1966.

Camacho wore his “Big Chief” outfit into the ring for his 1990 showdown with Vinny Pazienza. Photo / The Ring Magazine via Getty Images

“For Macho to defeat a major, important Mexican fighter, that was a crowning moment for him to the Puerto Rican people,”

said Henry Neumann Zayas, senator for the District of San Juan.

It was, of course, easier from that point on for Camacho’s evolving public persona to take on a life of its own. He announced his appearance on the scene, any scene, with shouts of “It’s Macho time!,” and his fanciful outfits for his ring entrances – Indian chief, Roman centurion, matador, gladiator and designer-loincloth Tarzan – delighted some and infuriated others.

“Over the years, people have said I’m crazy,” Camacho once said. “And I am. Crazy like a fox. My act is a smart one. It sold lots of tickets.”

But the metamorphosis of Camacho from a generally delightful free spirit to something less appealing to an increasingly large segment of boxing buffs was accelerated the night of June 13, 1986, when he squared off in Madison Square Garden against fellow Puerto Rican Edwin “Chapo” Rosario, a power puncher who would test him in ways that no one to that point had. Rosario hurt the heretofore nearly unhittable moving target several times, and although Camacho came away with a split-decision victory and retention of his WBC lightweight title, he would never again be quite the same fighter eager to engage at close quarters.

“There was a side of him that was never the same after the Rosario fight,” Farhood said. “He became more of a survivor and less of a fighter.”

There would be other changes as well. He shed himself of some of his closest confidants from the old neighborhood, and doubts that had never been there before, or had been subconsciously submerged, began to rise to the surface.

“Well, you know, it’s a learning process,” he said of his painful introduction to his profession’s harsher realities. “When you’re in a learning process, you get frustrated. You don’t quite see things right, you don’t understand. I wasn’t trained for this.”

One of those dismissed from Camacho’s inner circle was his first trainer, Robert Lee Velez, who had been with him since the future world champ was only 12. “He never had no education. He really didn’t have a trade. Boxing was a way out for him,” Velez said. “You know what, if that’s what you feel, I walk away. But I was no longer there to enforce anything. That’s when things fell apart.”

Raquel Camacho recognized what was happening to her younger brother, and she didn’t approve. “In the beginning of his career, everything was great,” she said. “It was about his family. After that, new people became involved. You know, different managers, different trainers, different people around him. So, he started changing.”

One thing, of course, did not change. According to mom Maria, Hector had been snorting cocaine since he was 17, if not earlier, and his use of and dependence on it grew along with his income and fame. Who knows, maybe his life’s path was predestined all along,

“We were living in an infested area with junkies on the floor,” Gonzalez said of their shared childhoods that were hardly Leave It to Beaver innocent. “Drug dealers trying to recruit us. There was nothing else, but there was always drugs. There was no food, but we had drugs.

“Macho always believed that his career was going to continue (even after his drug dependency became more prevalent). He got caught in that tide, in that riff, that his only companion was cocaine. Let me replace the fight with cocaine, let me hang out with cocaine. Cocaine is there for me. It’s not going to disappoint me. I don’t have to call cocaine 20,000 times and listen to a lie that the contract’s on its way, I’ve got a fight (the promoter) is working on. It’s the only thing that was consistent. It never let him down.”

Until, of course, it let him all the way down to a seemingly premature death.

There comes a point when even a strong person no longer can resist a rising tide, that the ability to continually rise above trouble ceases and one has no alternative but to sink into the muck. For Tim Ryan, the commentator for CBS’ telecasts of Camacho’s bouts during his meteoric rise to prominence, the convergence of past, present and future came on February 11, 1983, the night before the network’s prized boxing attraction was to fight John Montes Jr. in Anchorage, Alaska, an unusual fight site where the snowy landscape was blanketed in white powder of another sort.

“There was always something about Hector that was a lot of fun,” Ryan recalled. “He was hard not to like. But the night before the fight, we got a call in our hotel. One of his handlers, in great distress, said, `You’ve got to come over here. He’s trying to jump out of a window.’ He was completely out of his mind, drug-wise. We talked him into calming down and got him out of the danger. Then the concern was, how’s he going to be at fight time?

“The next day you wouldn’t have known anything had happened. There was domination there (Camacho won on a first-round knockout). He threw the punches he wanted to throw, he moved the way he wanted to move and he did what he wanted to do. He showed everything that he could be, the superstar that he could be. We were grateful for the fact that he had recovered and the fight went on, but it was a source of great concern to us from that point forward because we knew he was dealing with the demons.”

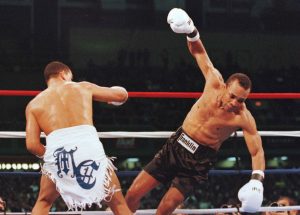

The last glimpse of the Camacho that was, or should have been all along, came the night of March 1, 1997, in Atlantic City when he was a well-worn 37, fighting an even bigger legend of the ring, Sugar Ray Leonard, who was 41 and coming off a six-year layoff. To the surprise of many, the Macho Man reached back in time to score a fifth-round stoppage.

Camacho trips up Sugar Ray Leonard in the first round of their 1997 middleweight fight at the Atlantic City Convention Center. Photo by Timothy A. Clary/AFP via Getty Images

“Camacho beating Leonard is downplayed by people because obviously Ray was literally at the end,” Farhood said. “But beating Ray Leonard the way Camacho beat him was impressive.”

Leonard doesn’t need to be convinced. He always has said of Camacho that “when he was at his best, it was a thing of beauty. I called a number of his fights. He was just slick, he was super-fast, strong-willed, confident. His footwork was just incredible. It was like he was on the dance floor. The movement, the uppercuts, the hooks … he had the whole package.”

So, how does someone who has so much fling it aside? That, too, is something Leonard, who at his best also had been a thing of beauty, can understand.

“The thing with fighters is that when we reach the top and then, when our careers come to an end, we search for that `And the new …’ There’s no better words to hear. I can’t even emphasize enough what that means to us. You beat the odds. And when we don’t have that any longer we go for something else to sort of duplicate it, with the alcohol or the drugs or whatever the case may be.

“I’ve been around Hector Camacho when he was doing his (drug) thing, because I was doing the same thing. I was no different than he was. But I was able to pull back and just stop.”

For all that he might have left on the table, let it be said that the Macho Man deserved his 2016 posthumous induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame. And his final record of 79-6-3, with 38 victories inside the distance, doesn’t tell all of it; in 673 rounds as a pro, he was knocked down only twice, in his 32nd bout, against Reyes Cruz, a 10-round unanimous decision victory on June 25, 1988, and in his 68th one, a 12-round, UD12 loss to Oscar De La Hoya on September 13, 1997. What’s more, he never lost inside the distance.

At the memorial service in Spanish Harlem to commemorate his life and times, thousands of Camacho’s fans poured onto the streets, waving Puerto Rican flags and shouting that it was still and forever would be Macho time. Hero-worship does not necessarily end with a gunshot or a fairy tale that has long since ceased to be smudge-free.

“To us, he was the Muhammad Ali of Puerto Rico,” one of the mourners said.

SUBSCRIBE NOW (CLICK HERE - JUST $1.99 PER MONTH) TO READ THE LATEST ISSUE