Then and Now: CompuBox Analyzes Mike Tyson-Roy Jones Jr. Exhibition

In the waning hours of March 1, 2003, Roy Jones Jr. sat in front of the world’s boxing media to bask in the glory of his greatest triumph to date — a lopsided 12-round decision victory over WBA heavyweight titleholder John Ruiz to become the first former middleweight titlist since Bob Fitzsimmons 106 years earlier to win a widely recognized share of the heavyweight championship. The speculation regarding the opponent for Jones’ first title defense ran rampant, and one of the first names that came up was that of Mike Tyson, a former two-time titlist who was long past his prime in terms of in-ring prowess but who still had the drawing power of his prime. For those reasons, Jones versus Tyson was a bona fide fantasy fight that promised to generate hundreds of millions of dollars. In fact, Las Vegas oddsmakers deemed Jones a 2-to-1 choice right after Jones-Ruiz.

All that changed during that post-fight press conference when Antonio Tarver, who recently won the WBC and IBF light heavyweight belts Jones vacated to fight Ruiz, took the microphone. The Orlando native declared that Jones (a Pensacola product) wasn’t even the best light heavyweight in Florida and demanded that Jones fight him. Jones could have dismissed Tarver’s challenge with a regal wave of the hand, but because it was issued so publicly and so forcefully, Jones abandoned the heavyweight division as well as the potential dream fight with Tyson. In a very real way, Tarver changed the course of boxing history, for he managed to goad Jones into burning off at least 18 pounds of muscle and fighting Tarver for his light heavyweight titles. Their first meeting, which Jones won by a hard-fought majority decision, would mark the beginning of a very long and precipitous decline. Meanwhile, Tyson, who scored a 49-second KO of Cliff Etienne in February 2003, went on to lose his final two fights against Danny Williams (KO by 4) and Kevin McBride (KO by 6).

All that changed during that post-fight press conference when Antonio Tarver, who recently won the WBC and IBF light heavyweight belts Jones vacated to fight Ruiz, took the microphone. The Orlando native declared that Jones (a Pensacola product) wasn’t even the best light heavyweight in Florida and demanded that Jones fight him. Jones could have dismissed Tarver’s challenge with a regal wave of the hand, but because it was issued so publicly and so forcefully, Jones abandoned the heavyweight division as well as the potential dream fight with Tyson. In a very real way, Tarver changed the course of boxing history, for he managed to goad Jones into burning off at least 18 pounds of muscle and fighting Tarver for his light heavyweight titles. Their first meeting, which Jones won by a hard-fought majority decision, would mark the beginning of a very long and precipitous decline. Meanwhile, Tyson, who scored a 49-second KO of Cliff Etienne in February 2003, went on to lose his final two fights against Danny Williams (KO by 4) and Kevin McBride (KO by 6).

Seventeen years after Jones-Ruiz, Jones will finally step inside the ring with “Iron Mike” but the rules that will govern their meeting will be different than normal. First, officially speaking at least, this battle will be regarded as an exhibition instead of a sanctioned match whose result will be included in their official records. Second, they will be fighting a maximum of eight two-minute rounds. Finally, each man will wear 12-ounce gloves instead of the 10-ounce gloves heavyweights usually sport. But if their pre-event rhetoric is to be believed, the action that will unfold will be much more intense than is usually the case with exhibitions. One reason is professional pride; each will want to be at his best against the other in terms of physical conditioning and mental fortitude. Another is that each is well-versed in boxing history and thus know that their “fight” will create fresh impressions about their abilities. And third, if a real fight breaks out, is bragging rights for the rest of their respective lives.

All these variables — along with the sight of Tyson and Jones in the same ring — make this event much more than the usual exhibition, and that’s why it has produced so much attention and inspired so much intrigue. What will unfold inside the ring at the Staples Center? That question will inspire many to plunk down $49.99 to find out.

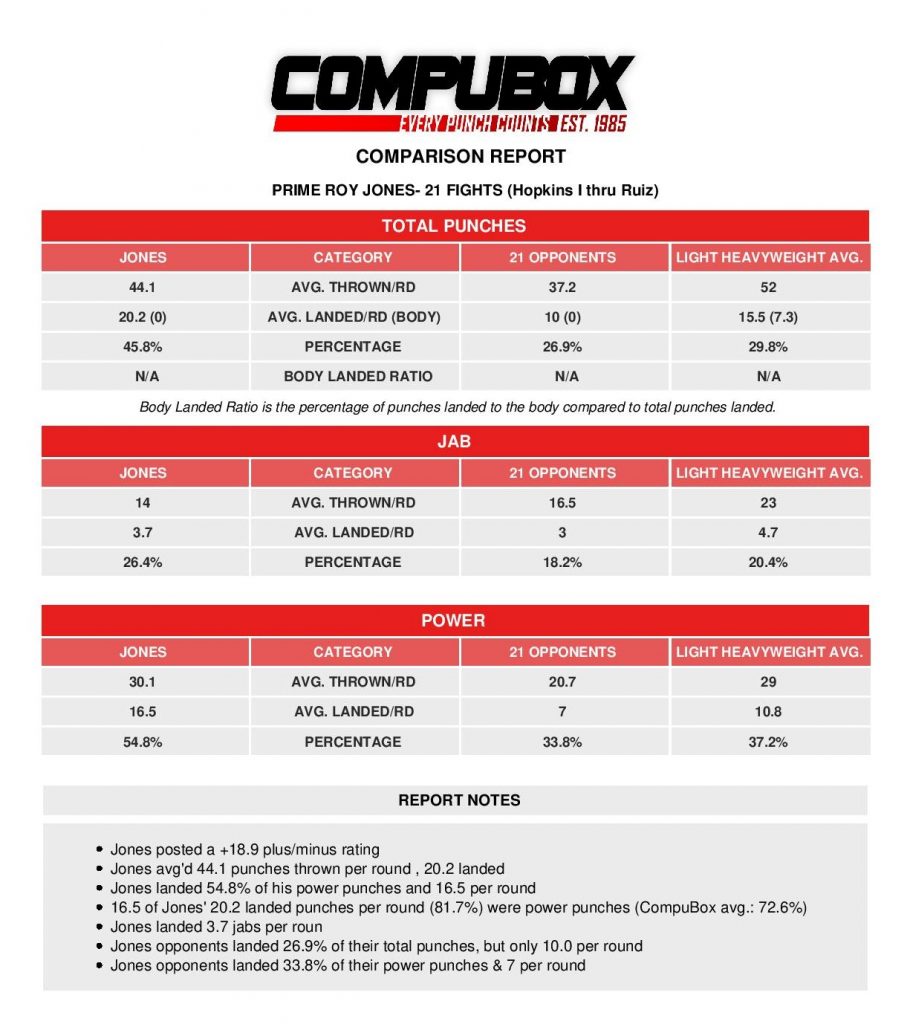

In Their Primes: When one looks at their respective bests, Tyson and Jones are remarkably similar when it comes to their statistical profiles on offense in that both are low output/high accuracy fighters. For the purposes of this analysis, Tyson’s “prime” is defined as the 15 CompuBox-tracked fights between his title-winning fight against Trevor Berbick in November 1986 and his second meeting with Donovan “Razor” Ruddock in June 1991 — his final fight before being sentenced to prison. As for Jones, his best is made up of the 21 CompuBox-tracked fights between his first fight with Bernard Hopkins in May 1993 through his triumph against Ruiz in March 2003 — a much longer prime during which Jones was deemed boxing’s best pound-for-pound fighter by The Ring twice (from April 1996 to March 1997 and from October 1999 to June 2000; the Ruiz win would begin his third and final tenure which would end with the Tarver KO loss in May 2004). As a point of comparison, Tyson was The Ring’s No. 1 pound-for-pound fighter when the list debuted in its January 1990 issue and he would remain at the top of the list for five issues until his loss to James “Buster” Douglas.

The typical heavyweight averages 44.6 punches per round but the work rates of Tyson (34 per round) and Jones (44.1 per round) were below that benchmark. The same could be said for both mens’ jabs; the heavyweight average is 20.5 attempts and 5.0 connects per round but Tyson averaged 11.1 attempts and 3.2 connects per round while Jones’ jab (14.0 attempts and 3.7 connects per round) also fell below the light heavyweight norms of 23 attempts and 4.7 connects per round. But they more than compensate for these deficits with superior accuracy in all phases, and the numbers are stunningly similar: Tyson landed 45.9% of his total punches compared to Jones’ 45.8%, Tyson connected on 28.8% of his jabs compared to Jones’ 26.4% and Tyson landed 54.4% of his power shots compared to Jones’ 54.8%. Because Jones averaged 10.1 more punches per round, he inflicted more numerical damage in terms of connects per round (20.2 to 15.6 overall; 3.7 to 3.2 jabs and 16.5 to 12.4 power). They also boasted an aggressive punch selection as power punches comprised 67.1% of Tyson’s attempts and 79.5% of his connects compared to 68.3% of Jones’ attempts and 81.7% of his connects.

But while their offensive numbers are closely aligned, Jones was the better defender, mostly because Tyson jettisoned his trademark Cus D’Amato head movement during much of his title reign. Tyson’s opponents landed 34.1% of their total punches, 28.1% of their jabs and 39.6% of their power punches while Jones’ opponents connected on just 26.9% of their total punches, 18.2% of their jabs and 33.8% of their hooks, crosses and uppercuts. Therefore, the Prime Jones boasted a plus-18.9 plus/minus rating (the difference between a fighter’s total connect percentage compared to that of his opponents) while Tyson’s was plus-11.8.

One point of difference favoring the Prime Tyson was that he faced less incoming fire from opponents — probably because they were justifiably fearful of what would be coming back. Tyson’s 15 opponents averaged only 30.5 punches per round and landed 10.4 total punches per round, 4.1 jabs and 6.3 power punches per round while Jones’ 21 foes averaged 37.2 punches per round, 10 total connects per round, 3.0 landed jabs per round and 7.0 power connects per round.

TYSON NOTES:

- IS THE YOUNGEST FIGHTER TO WIN A WIDELY RECOGNIZED PIECE OF THE HEAVYWEIGHT CHAMPIONSHIP (20 YEARS 150 DAYS)

- RECORD IN WIDELY RECOGNIZED WORLD TITLE FIGHTS: 12-4 (10 KO)

- TWO-TIME RING MAGAZINE AND BWAA FIGHTER OF THE YEAR (1986, 1988)

- NAMED 14TH GREATEST HEAVYWEIGHT OF ALL TIME BY RING MAGAZINE IN 1988 AND THE 72ND GREATEST FIGHTER OF ALL TIME IN 2003

- INDUCTED INTO INTERNATIONAL BOXING HALL OF FAME (2011), NEVADA BOXING HALL OF FAME (2013) AND SOUTHERN NEVADA BOXING HALL OF FAME (2015)

JONES NOTES:

- TWO-TIME NATIONAL GOLDEN GLOVES CHAMPION (1986, 1987) AND SILVER MEDALIST AT THE 1986 GOODWILL GAMES

- 1988 OLYMPIC SILVER MEDALIST (LOST FINAL TO SOUTH KOREA’S PARK SI HUN IN SOUTH KOREA; A VERDICT WIDELY CONSIDERED TO BE THE WORST IN OLYMPIC HISTORY)

- REPORTED 122-13 AMATEUR RECORD

- PROFESSIONAL CAREER BEGAN WITH 17 CONSECUTIVE KOs

- RECORD IN WIDELY RECOGNIZED WORLD TITLE FIGHTS: 22-3 (14 KO)

- HAS FOUGHT 22 MEN WHO WERE CHAMPIONS SOMETIME IN THEIR CAREERS (18-8, 8 KO)

- 1994 RING MAGAZINE FIGHTER OF THE YEAR AND 2003 WORLD BOXING HALL OF FAME FIGHTER OF THE YEAR (HAS NEVER WON BWAA FIGHTER OF THE YEAR AWARD BUT WAS NAMED THE ORGANIZATION’S FIGHTER OF THE DECADE FOR THE 1990s)

Most Recent Form: For this portion of the study, the numbers were drawn from Tyson’s last four CompuBox-tracked fights (KO 6 Brian Nielsen, KO by 8 Lennox Lewis, KO by 4 Danny Williams, KO by 6 Kevin McBride) and Jones’ last five tracked bouts (L 12 Bernard Hopkins II, KO by 10 Denis Lebedev, KO by 4 Enzo Maccarinelli, KO 8 Bobby Gunn and W 10 Scott Sigmon).

Tyson’s offensive numbers remained much the same as his prime as he averaged 35.6 punches per round (1.6 more per round than his best) and connected at very high rates (39.3% overall, 17.1% jabs, 50.2% power compared to 45.9% overall, 28.8% jabs and 54.4% power). For Tyson, the major sign of erosion was on defense as his opponents were more willing to let their hands go (43.4 punches per round compared to 30.5 during Tyson’s best years) and they connected with much more frequency (40.6% overall, 36.7% jabs, 43.3% power compared to 34.1% overall, 28.1% jabs and 39.6% power). Thus, Tyson’s opponents managed to land more punches per round overall (17.6 to 14.0) and more jabs (6.6 to 2.0) while Tyson scraped out a 12.0 to 11.0 edge in landed power punches per round. As was the case during his best years, power shots made up a big part of Tyson’s offense (67.1% of attempts and 85.7% of connects during the post-prime years compared to 67.1% and 79.5% during the prime years).

As for the post-prime Jones, that version threw far fewer punches per round (35.0 compared to 44.1 in his prime) but he still managed to connect with excellent but lesser frequency (35.4% overall, 17.9% jabs, 44% power compared to 45.8% overall, 26.4% jabs and 54.8% power during his best years). Jones remained aggressive with his punch selection as power shots comprised 66.9% of his attempts and 83.1% of his connects compared to 68.3% and 81.7% respectively. Like Tyson, Jones’ major symptom of erosion was on defense as opponents hit Jones with 31.8% of their total punches, 15.8% of their jabs and 39.4% of their power punches — a far cry from the figures he yielded during his best years (26.9% overall, 18.2% jabs, 33.8% power).

Prediction: Tyson’s performance in his final fights was adversely affected by his negative mindset. “I was happy to leave the ring,” he told the New York Post in late-October. “I dreaded being in the ring at that time. I was a whole different person back then.” But now, more than 15 years after his last fight, his passion for boxing has been resurrected; “I have the desire to do this now and the will to do this now. I’m just ready to do this and I feel really great. I want to see how great I look. I just feel magnificent.” Because Tyson was guided by Cus D’Amato — who placed an enormous emphasis on mental strength — his performances in the ring were greatly dependent on his emotional and mental state, and, for this event at least, it will be the best it has been in many years.

As for Jones, he has the distinct advantage of having his last official fight take place less than three years ago. And, against Sigmon, the 49-year-old Jones was excellent on offense (58.5 punches per round, percentages of 48.5% overall, 28.6% jabs and 51.6% power, and connect leads of 284-226 overall, 22-1 jabs and 262-225 power) and decent on defense (33.4% overall, 4.2% jabs, 34.5% power). He was so relaxed and in command that he engaged in mid-fight conversation with Pensacola ringsiders, landed trick punches and radiated positivity.

If this were a “real” fight, the conventional wisdom is that Tyson should be the heavy favorite. Power is the last asset a great fighter loses and, at 54, Tyson may still have much of it. Of course, the 12-ounce gloves may blunt some of Tyson’s clout but his hand speed — at least based on the short videos he released — appears to remain above average for anyone, much less a man of his vintage. The two-minute rounds should also help in terms of preserving Tyson’s stamina, an asset that has never been questioned about Jones.

Conversely, the first gift a great fighter loses is leg strength and Jones lost that many years ago. Also, he has been knocked unconscious multiple times in his career (Glen Johnson, Denis Lebedev, Enzo Maccarinelli) and in Tyson he will be facing a much bigger man with a much bigger punch. In short, Jones will be fighting Tyson with aged legs and a dodgy chin. If a genuine rumble breaks out, and if Tyson hurts Jones, Tyson, renowned for his killer instinct, will win by KO. But if Jones can survive the opening wave — let’s say the first three two-minute rounds — he could pick apart a potentially winded Tyson, who, when pressured or frustrated, has behaved extremely erratically (the Holyfield bite fight, the attempts to break the arms of Frans Botha and Kevin McBride, and so on).

Both have strengths they can emphasize and both have weaknesses the other fighter can exploit. If this exhibition becomes a “shoot,” the pick is Tyson by TKO, but the guess is that both men will generally honor the unwritten rules dictating exhibitions. This event could go the way of the three Julio Cesar Chavez Sr.-Jorge Arce exhibitions — enough two-way action to please the viewers and to generate the sense that both are nearing the razor’s edge of reality, but once they approach that edge they will pull back. If that happens, then the prediction will be that a good time will be had by all — audience and boxers alike.

SUBSCRIBE NOW (CLICK HERE - JUST $1.99 PER MONTH) TO READ THE LATEST ISSUE