Best I Faced: Murray Sutherland

To talk to him, you couldn’t tell that Murray Sutherland is now 67. You also couldn’t tell that he fought the likes of Michael Spinks (twice), Matthew Saad Muhammad, Tommy Hearns, Eddie Davis, JB Williamson, Robbie Sims, Bobby Czyz, Wilford Scypion, James Kinchen and Alex Ramos in his 62 professional fights.

The transplanted Scot, who moved to Canada from Edinburgh in 1974, has been struggling with a sciatic nerve issue in his right hip but otherwise is in great health. It was only when he went to pick something up in work when that disaster struck.

That’s right, he’s 67 but he still works.

“I didn’t make enough to retire,” he laughed. “Back in those days you didn’t make any money if you fought for the title, you only made money after you won the title. I see these things, like Floyd Mayweather fighting the MMA guy [Conor McGregor] for $100 million. My God, unbelievable – and it’s sickening!” he joked. “But anyway, I left boxing and the guy that used to manage me, Art Dore, I went to work with him. He’s an entrepreneur with asbestos removal and stuff like that and I worked with him for about 15 years, ran a company for him and I made a good living at it – but I’m still working.”

But he’s also happy with that, content in life, content with his career and he holds a record that will never be broken as the first ever world super-middleweight champion, when he won the IBF title against Ernie Singletary.

He’s thankful not to be another hard luck story.

“I just feel bad for some of the fighters who end up like that,” he said. “Fortunately, I’ve got a beautiful wife and a couple of kids and four grandkids, we’re very family orientated, we stick together and we all live in the same town…”

Sutherland started boxing in Scotland where he had around 20 amateur fights but when he moved to Canada boxing went on the backburner and he got involved with martial arts, firstly karate and then kickboxing.

That led him back to boxing where he started working with the Summerhays boys, Gary, Johnny and Terry and he’d travel from Hamilton, Ontario to Brantford to work with them.

But he’d left for Canada to find work.

“In ’74, around that time the miners went on strike in Britain and they shut down all the manufacturing and I was a machinist at the time and the boss came to me and said, ‘Look, we’re on short time, if you want to work your 40 hours in three days you can do it. I said, ‘Hell, I’m 20 years old, I’m not working times like that’. My older brother had moved to Canada in the January of ’74 and he contacted me and he was also a machinist and told me the company he was working for needed more people and they’d fly me over, take care of me for a month or two until I got on my feet and that’s how I moved to Canada.”

Sutherland was always in fabulous condition, ripped to the bone and ready to go. He stayed in shape between fights, not that there was much time in between contests in those days and certainly not for him.

It was his father’s work ethic that saw him cut no corners. He’d preach to Murray about the benefits of being in condition when his son was just 10-years-old.

“He’d say you can’t control your natural gifts and when I got older and I realized what he was trying to preach to me I hadn’t appreciated it because I’d wanted to go and play football and stuff like that, I wanted to play games with my buddies outside but he would drag me to the boxing gym,” Sutherland explained. “He instilled values in me that I relied on later in my life. The only thing you can really control is your conditioning, because you’re the one who’s going to do it and if you don’t do it you’ve only got yourself to blame.”

Sutherland fought for promoter Art Dore and was boxing on toughman shows in legit pro contests that would top the bill of toughman events.

Yes, it was a way of inflating a record but it also put valuable experience in the bank.

“Hell, I fought two nights in a row one time in Wisconsin, I fought on a Friday night and then on a Saturday night and that got me two more wins on my record,” he recalled. “I’m not going to tell you that these guys I was fighting were world beaters by any stretch of the imagination but to build up my record and get my record up, that’s what we did. It was all experience, it was conditioning, it was preparing to fight, you’d never take the guy lightly or think, ‘Oh, Art’s found me another bum to beat up’. It was always a case of train like you were stepping in the ring with Matthew Saad.”

After just 10 fights, however, he was handed a very real test when he took on New Jersey veteran Richie Kates, one of the dangermen of a deep and dangerous division at 175 pounds.

Murray lost a 10-round decision.

“He taught me a few things,” Murray said of the man who’d just missed out on taking the WBA title from Victor Galindez. “In the seventh round I was in close and I went to headbutt him, and he looked at me and he said, ‘You want to fight dirty?’ And he elbowed me right in the face. I’d only had nine or 10 fights but he taught me a lot. He taught me what a seasoned pro can do. I didn’t think it [the loss] was the end of the world. It was my career. I knew it wasn’t going to be an easy road, I just took it for what it was, it was a learning experience and I went back to the gym a week or so later and I got right back into it.”

A few fights later he took a bout at four days’ notice against a novice Michael Spinks, the 1976 Olympic gold medallist. It was in upstate New York and Sutherland flew in the day after he got the call.

“I knew Michael was special even before we fought,” he said. “I’d watched him in the 1976 Olympics and if someone had said then I’d be fighting Michael Spinks, I would have been like, ‘Yeah, right.’ But you’ve got to mature into a really good fighter. You can have the skills, the conditioning but you have to mature into being world championship calibre. At that point I wasn’t world championship calibre. I wasn’t experienced enough, meaning to step up to the plate and to hang in there and strategize… It takes a long time.”

But he did last the course and took Spinks 10 rounds.

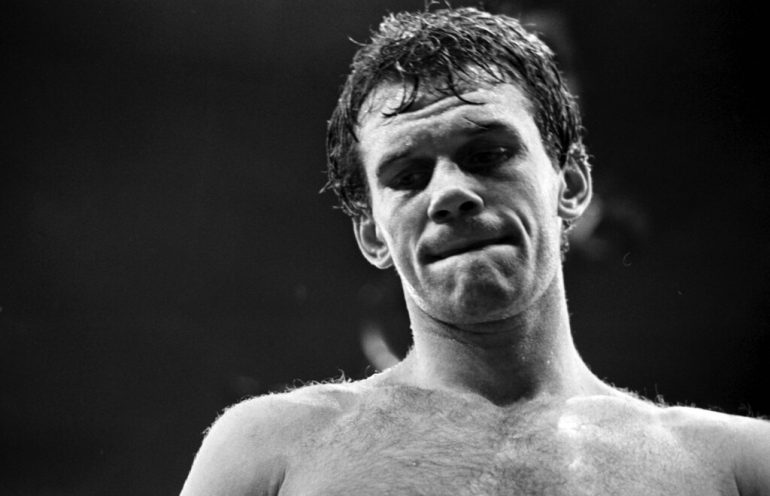

Matthew Saad Muhammad (L) throws a punch against Murray Sutherland. Photo from The Ring archive

Less than a year on Sutherland took on another high-profile assignment and when he became Matthew Saad Muhammad’s eighth and final victim of a torrid WBC title reign.

“At certain times, I possibly thought his mileage was too high to face a young contender like me but I was kind of in awe of him. When I was living on Canada, every Saturday or Sunday or sometimes both, they’d have title fights on the TV and we used to watch these guys. I used to watch Matthew Saad Muhammad any time he fought and to step into the ring with someone like that? It was pretty awesome. He was a warrior. He was like one of those Viking guys. It didn’t matter what you hit him with, he kept coming. I’ll be truthful with you, the first round I threw a couple of jabs and a right hand I hit him with all three punches. Flush. Right in the face. And I said to myself, I can’t believe this guy is so easy to hit. The thing is, you could hit him with a baseball bat and he’d keep coming and coming and coming.”

Matthew’s bottom lip was grotesquely split in two and a squeamish doctor or official may have considered stopping it.

But Saad did what he did, he warmed into the fight, turned the screws and then closed the show in Round nine.

“It was an overhand right,” Murray went on. “I can remember it vividly. He backed me up into my corner with a couple of jabs and then all I saw was his shoulder rotating and the next thing I knew, I was on my ass thinking, How the hell did I get here?”

The Scot, who wore tartan shorts, made it back to his feet but the fight was over. There was a protest but the chance had come and gone.

Four wins later and Murray was back in with Spinks, but it was a changed Spinks who’d had 10 more fights – including wins over Yaqui Lopez, Eddie Mustafa Muhammad, Marvin and Vonzell Johnson and Mustafa Wasajja – and won the WBA title. “This Spinks was a way different fighter to how he was when I fought him the first time,” Murray explained. He had matured into a true champion and he was a light-heavyweight at 175. I walked around the street at 176-178. I wasn’t a big light-heavyweight whereas guys like Michael Spinks used to walk around at 200, 205, and they’d trim down. When they stepped in the ring basically they had the power of a 200-pounder and the punching power of these bigger light-heavyweights like Matthew Saad and Michael Spinks, they just firebombed me. When we got into the centre of the ring to touch gloves we were both gloved up, he had Reyes gloves [known puncher’s gloves] on and I had Everlast gloves on. What does that tell you? I can look back on it now and laugh but that’s where maturity would have intervened. If I knew then what I know now I would have said get some new gloves on him or get them on me but we ain’t fighting.”

Sutherland was stopped in eight and just two months later he was boxing in the searing Las Vegas heat on the Larry Holmes-Gerry Cooney bill.

“I was in it for the money,” Murray continued. “I looked at it as a job. That’s why I didn’t mind getting up at 0630-0700 and running five miles a day, I didn’t mind going to the gym because that was my job. Too many people think it’s a hobby that you make some money off of. It’s not. It was my job, that’s what put food on the table so when a fight came along and the money was right, I’d take it.

“Cooney and Holmes was the biggest money fight that had ever happened at the time and it was summer in Las Vegas outdoors, hello!” joked the pale Scot. “It was 120 degrees on the ring apron when I stepped into the ring at 2.30 that afternoon. I had blood blisters on the soles of my feet when I got back to the dressing room, and I only went six rounds with him. “It was just unbelievable. The heat! No excuses, he beat me, he stopped me in the sixth but I was just burned out.”

Davis was also another legit light-heavy and it was for the USBA title but Sutherland now felt that if he was going anywhere, he’d have to start by going down in weight.

“After I fought Eddie Davis, I decided this is too much. I’m going in there with a peashooter and I’m fighting guys with canons, so let’s drop down to middleweight and fight at 160 pounds, which I did without any problem,” he added. “I took about eight months to get down there and I held it [the weight] for two years. I fought James Kinchen right after a tough fight with Alex Ramos and I was just burned out. I didn’t have the fire or the tenacity to kick his ass.”

Hearns lands a right hand against Sutherland. Photo from The Ring archive

By this point, he’d also lost at 160 pounds to Tommy Hearns, a man who not only boasted punching power but who Sutherland said was underrated defensively and skill-wise.

He’d also had a successful trip to Australia where he’d outpointed Tony Mundine over 10.

“I loved it there and they treated me like a king out there,” he recalled.

In March 1984 he boxed Singletary for the first ever world title at 168. He didn’t know he was starting the wheels in motion of a title that would still be around several decades later and hosted some of the sport’s biggest names.

“I really didn’t give it much thought,” he said. “It was a chance to win an alphabet soup title. “What the hell is the IBF? But I look back on it now and say I would much rather have fought for the WBC title because I fought it was the more prestigious title and when I fought Matthew Saad Muhammad I’d seen that green belt and I loved that belt, I would have rather had that one. Ernie was tough, he was strong. Before we fought him, my manager said, ‘This is Tommy Hearns’ number, give him a call.’ I called Tommy and he said, ‘I hear you’re fighting Ernie. Well, don’t try to knock him out, I tried and all I did was hurt my hands.’ He could take a punch, so Tommy said just box him. And that’s what I did and that was one of the last 15 round fights.”

Ernie never fought again and Murray lost the title in his first defense in Seoul four months later.

“It was a hard road but I looked on it as a job,” he reflected of his run of big fights. “I wasn’t out to make a name or be written in history or anything. Basically, it was a payday for me, and that meant I could go another couple of months without having to fight and could still pay the rent. It was pure money. When I won the title and took it to South Korea and lost it to Chong Pal Park, people say, ‘Why the hell did you go over there? Why didn’t he come over here?’ Because the money wasn’t here. Nobody knows him over here. The money was in South Korea, that’s why I went there. They paid me $75,000 for the fight and that’s the best money I’ve ever made.”

Within a few months and after a few more victories, Sutherland knew the end was near.

When asked why he retired having lost two of his last three fights to Bobby Czyz (UD 10) and Lindell Holmes (TKO 3) he said the answer was in the question.

“Those two fights,” he admitted. “I knew I had lost it. I’d said by the end of ’85 I want to get out of boxing and want to move on to something else. The Lindell Homes fight was scheduled for November but they lost the TV date or something so they postponed it to February but I knew I was done with boxing after that. I had no fire left in me. I’d had enough. My two kids were babies and here we are in 2020 and I can converse with you and still remember everything. I knew I could have stuck around another couple of years and made some paydays against up and comers but I didn’t want that, I wanted to move on.”

It proved a prudent call. Murray sounded absolutely fantastic even though he perhaps didn’t get the financial windfall he might have from his 47-14-1 (39 KOs) career.

But it’s important to go back to the start with Murray when you look as his health now after everything he’s experienced. He talked about his father’s discipline and taking the job seriously. He also learned to keep himself safe.

“I learnt my trade back in Scotland and back there its referred to the art of self-defense and they’d teach you defense,” said Sutherland, who doesn’t watch many fight today. “That was my saving grace, that I had a great defense.”

BEST JAB

Michael Spinks: Probably Michael Spinks, because like Larry Holmes he used to step in on his jab and a lot of people throw the jab from the shoulder but what he would always do, and what I have always done, is shift that bodyweight forward, take a little hop with it and it gives you about an extra six inches and it gives you more power.

BEST DEFENSE

Tommy Hearns: I first met Tommy Hearns when he was like 17 years old and he fought the main event of a show when I was on the undercard so I’d been following him. He had won the AAU boxing championships in the amateurs and I knew he was good. Guys that are big punchers, that’s what they get a name for but Hearns, Spinks, guys like that, were tremendous boxers too. They had great defense, great offense, they’d slip punches well, they had the whole package, that’s why they were great champions.

BEST HANDSPEED

Hearns: Hearns again.

BEST FOOTWORK

Spinks: I really never paid much attention to footwork. Spinks.

SMARTEST

I hate to be repetitive but those two, Spinks and Hearns, are the only two that really stick out in my mind.

STRONGEST

Spinks: Definitely.

BEST CHIN

Matthew Saad Muhammad: Oh my God I hit him with some right hands that I’ve hit people with before and they’ve gone to sleep. But he’d just look right back at you and walk at you with that Mummy walk he used to do.

BEST PUNCHER

Spinks: He was way ahead of Saad.

BEST BOXING SKILLS

Mario Maldonado: I’d say Mario Maldonado, he was a Puerto Rican I’d fought in Atlantic City, and the guy was good. I beat him but he messed me up pretty badly. I came home with sunglasses on.

BEST OVERALL

Spinks: Spinks was the best overall.

READ THE LATEST ISSUE OF THE RING FOR FREE VIA THE NEW APP NOW. SUBSCRIBE NOW TO ACCESS MORE THAN 10 YEARS OF BACK ISSUES.