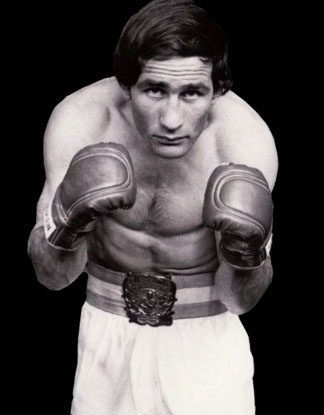

Former titleholder Miguel Angel Castellini dies at 73 in Argentina

The old mantra of not giving up even when someone puts a gun to one’s head is as exaggerated as it is unprovable. Very few people can claim to have faced those fearful odds and then go on to fulfill their pledge. Most of them do not. Only a fewer number of them can claim to have had a second chance to deliver on their promise.

Former junior middleweight titlist Miguel Angel Castellini was definitely one of them.

Castellini passed away at around midnight this past Tuesday, October 27, after a 40-day stay in Hospital Juan A. Fernandez in Buenos Aires, from complications of several health conditions that included a bout with pneumonia coupled with a positive test for COVID-19. He had also suffered seven strokes in the past eight years. He was 73. He is survived by his wife Karina, and his sons Miguel Jr., Aldana and Maximiliano.

The slings and arrows of life caught up early with Castellini, who frequently ran away from his home in Santa Rosa, La Pampa, to find fights all over Argentina and sometimes linger around town after each fight to find any extra work. One of those trips took him to Buenos Aires, and he ended up being dragged into the huge magnet of the fabled Luna Park, which was South America’s answer to both the Madison Square Garden and Stillman’s Gym back in the day, boasting sold-out crowds weekly as well as a training facility under the bleachers where dozens of fighters plied their trade every day.

He became junior middleweight champion of Argentina in 1972, earning a reputation as a fearless boxer-brawler who was unafraid to mix it up with some of the hardest-hitting local contenders of the day, including knockout artist Ramon La Cruz and many others.

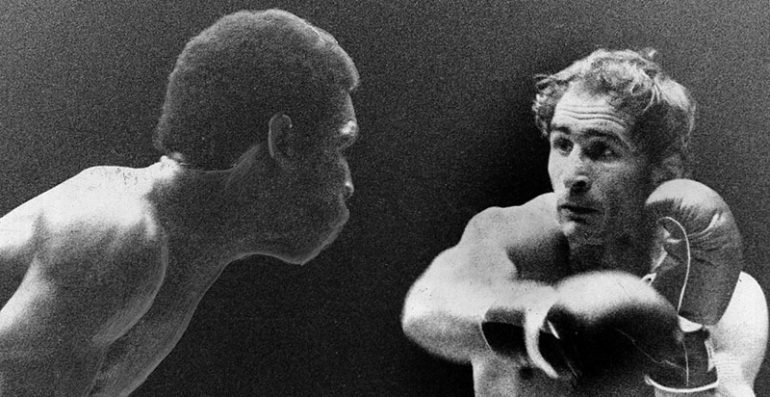

Nicknamed “Cloroformo” (Chloroform) thanks to the numbingly powerful nature of his punches, Castellini’s first tete-a-tete with the ostensibly more powerful barrel of a gun would come in October of 1976, when he traveled to Spain to face Jose Duran at the local Palacio de los Deportes and left after 15 rounds of action with the WBA belt around his waist and a rain of projectiles of all kinds falling over his head as he headed for the exit, in a harbinger of things to come.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vqJnVpdxVhQ

Less than five months later, his Hall of Fame manager Tito Lectoure made one of the most ill-advised decisions of his career when he took Castellini to Nicaragua at the height of one of Latin America’s most brutal dictatorships, headed by Anastasio Somoza. Castellini would end up losing his title in his first defense against Eddie Gazo, a then-corporal in Somoza’s ruthless Guardia Nacional who was later promoted to sergeant just for becoming champion.

Gazo not only had Somoza’s financial support in his title-winning effort: the local Estadio de Beisbol de Managua was filled to the brim with uniformed armed forces personnel, who celebrated Gazo’s onslaughts and attacks by firing their weapons into the air. One of them made a significant contribution to Gazo’s championship-winning effort when he allegedly climbed the ring stairs brandishing a handgun, and impressed upon Castellini’s entourage the idea that Gazo had to win the bout if they all wanted to make it out of the venue alive.

Unaware of this circumstance, the Argentine public never forgave Castellini for his poor performance and for the listless way in which he lost his title, which back then was only the sixth pro boxing championship ever achieved by an Argentine fighter. To make matters worse, Castellini had the unenviable task of sharing the spotlight at the time with two of Argentina’s most popular champions in Carlos Monzon and Victor Galindez (Pascual Perez, Horacio Acavallo and Nicolino Locche completed the roster up to then), and he would soon fall in disrepute, retiring in 1980 with a final record of 74 wins, 8 losses and 12 draws, with 51 KOs.

Unaware of this circumstance, the Argentine public never forgave Castellini for his poor performance and for the listless way in which he lost his title, which back then was only the sixth pro boxing championship ever achieved by an Argentine fighter. To make matters worse, Castellini had the unenviable task of sharing the spotlight at the time with two of Argentina’s most popular champions in Carlos Monzon and Victor Galindez (Pascual Perez, Horacio Acavallo and Nicolino Locche completed the roster up to then), and he would soon fall in disrepute, retiring in 1980 with a final record of 74 wins, 8 losses and 12 draws, with 51 KOs.

In his long boxing afterlife, he ran a very colorful boxing gym not too far from the Luna Park Stadium in which he had so many memorable nights. The location of his gym, right in the middle of the busy Buenos Aires downtown and financial area, led to a wave of white-collar subscribers among which there were many women. Castellini is thus credited with being one of the first gym owners to allow women to train in his gym, which played a great role in the surge of female boxing in a country that now boasts a few dozen female titlists. The dozens of posters and newspaper clippings that covered the gym’s walls provided the background for many photo sessions and served as a location for several TV shows and films.

One of the numerous yellowing magazine articles that covered his gym’s walls remains, to this day, one of Argentina’s most venerated ringside reports ever written.

During a short visit to the country in which he spent his youth, writer Julio Cortazar, an avid boxing fan who wrote some of the best boxing short stories in Spanish-language literature, accepted an invitation to sit at ringside at Luna Park. On that night, in April of 1973, Doc Holliday (a history student at the University of Columbus, Ohio, who had allegedly brought his books along with him in order to prepare for an exam back home in the following week), stepped into the ring with a 12-4 record to serve as a test himself for the already studious Castellini.

After receiving an invitation from a staff member of the nation’s most popular sports media outlet, Cortazar’s impressions from that night ended up reflected in a highly critical, one-page fight report. After being initially enraged by the report published by El Grafico magazine, Castellini was later inspired by it to step up his game ahead of his first title fight, and his initial frustration with Cortazar’s scathing criticism was credited with helping him improve his skills – and ultimately win the belt.

The rest of Castellini’s career, with the usual ups and downs, was buried among the great fights of the time, in which Luna Park hosted two cards per week, year-round, often featuring some of the best matchups of the country’s golden era of boxing, in which he shared the billing with popular fighters such as Ubby Sacco, Horacio Saldaño, Oscar “Ringo” Bonavena, Gustavo Ballas and many others. He also served as a sparring partner for Victor Galindez (one of his closest friends in the fight game) and Carlos Monzon, whose arrogance he despised so much that he intentionally punished him in the ring at every session until Monzon’s handlers aborted the proceedings, much to Castellini’s solace.

Castellini’s unfair loss in Managua plagued him during the rest of his life.

“I reproached myself for a long time after that”, said Castellini, towards the end of his life, to Ernesto Cherquis Bialo, dean of Argentine boxing writers and one of the catalysts of Cortazar’s short-lived ringside reporting career. “I was never able to recover from that. People didn’t understand what happened. Going to fight in Nicaragua, at such a bad time in history, was a terrible mistake. I was never the same again”.

His career dwindled, and in a tragic deja-vu of his early days he spent his final years fighting all over Argentina in search for a redemption that would come, as it is always fitting, at the very end of his ring life.

On September 20, 1980, Castellini finally lured Eddie Gazo for a reprise of their fateful encounter in Managua. Under the roof of the Luna Park, and under the gaze of one of the most demanding and unforgiving boxing audiences anywhere in the world, “Cloroformo” materialized his magic on the canvas of the venerated venue one last time, brutally beating and stopping Gazo in the ninth round and then marching into retirement with a modest and bittersweet measure of redemption under his belt.

At the very least, Castellini proved in his final moment under the ring lights to be anything but gun-shy.