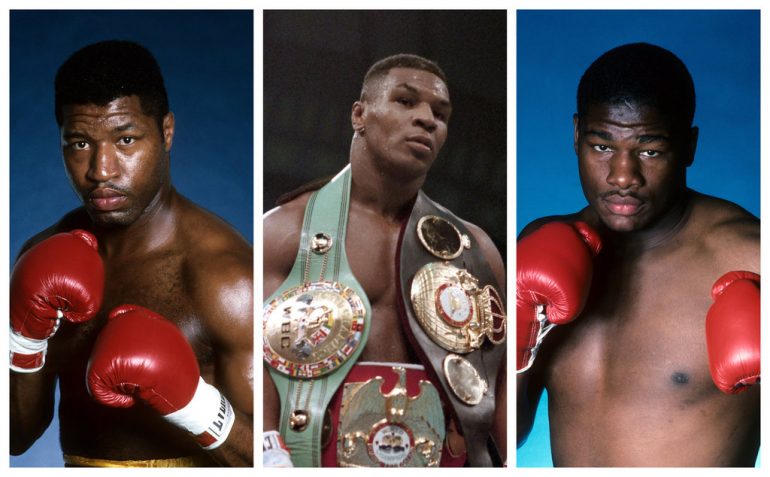

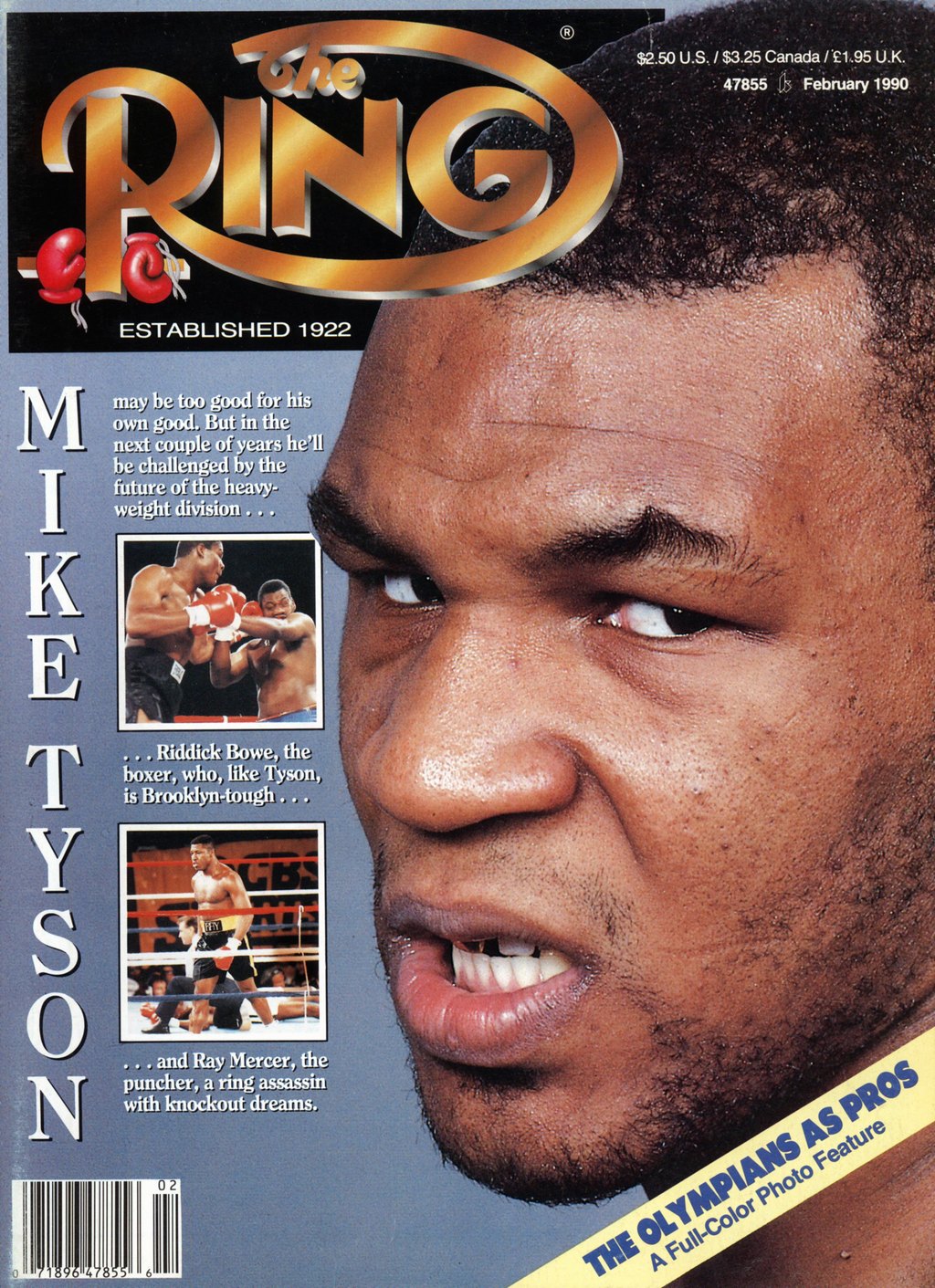

From The Archive: Riddick Bowe and Ray Mercer take aim at Mike Tyson

Editor’s Note: This feature originally appeared in the February 1990 issue of The Ring Magazine.

By Steve Farhood

THE PUNCHER: “I can brawl; that’s what it’s gonna take. It’s gonna be a knockdown, drag-out war.”

I lay in bed, I think about it all the time. Every night. Five times a night I think about Mike Tyson.

It’s gonna be like the last day of my life, and I gotta fight to get out. It’s gonna be a war. People are gonna be saying, ‘Ray Mercer comes to fight.’ People are gonna be into it. As an amateur, Mike Tyson was knocked out. And when someone tells me a fighter’s been kayoed, a green light goes on. This guy can be knocked out! It’s gonna be a kayo, and I’m gonna jump up. The feeling will be like when I won the Olympics. All the pressure’s off.

At the press conference, I’m gonna tell people the easy part is over. Keeping the title is the hard thing.

Then, me, my trainers, and my manager are gonna rent a jet and fly to the Bahamas for three weeks. Stag.

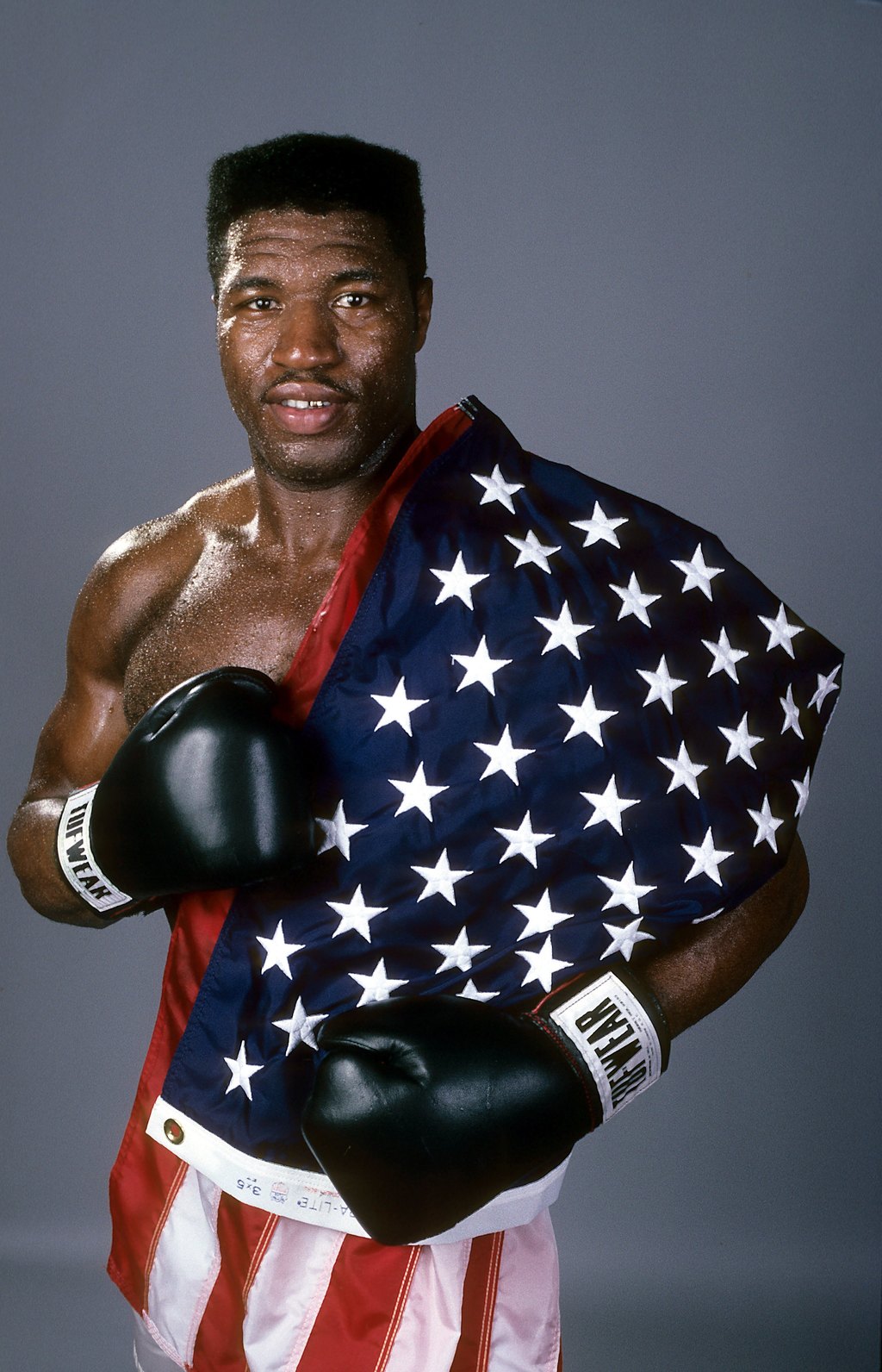

RAY MERCER ADMITS that when he knocks out an opponent, when his left lands right and that electric feeling shoots all the way up his arm, it makes him feel very good. And, he says, when he begins to knock out a better quality of opponent, it’s going to feel even better.

RAY MERCER ADMITS that when he knocks out an opponent, when his left lands right and that electric feeling shoots all the way up his arm, it makes him feel very good. And, he says, when he begins to knock out a better quality of opponent, it’s going to feel even better.

If Mercer ever knocks out Mike Tyson . . .

“Coming up in the amateur ranks, I learned how to box,” he said. “I can box. But a boxer has yet to beat Mike Tyson. They come up empty handed. They go in there expecting the worst, that they’re gonna go down, that they’re gonna get hurt. I can punch and brawl, and that’s what it’s gonna take to beat Tyson. My attitude is that I’m gonna get hit, and hit good, but I’m gonna hit him as much as he hits me. It’s gonna be a knock-down, drag-out war. And I’m gonna be the heavyweight champion of the world.”

A professional for less than a year, Mercer is approaching Tyson like a helmetless biker speeding into a brick wall. As of this writing, the Olympic gold medalist hadn’t boxed more than four rounds in any single fight, but had already reached 10-round main-event status. In December, he’s scheduled to face James Tillis, everyone’s favorite heavyweight trial horse; that’s a sure sign that a bout with a top-10 contender isn’t far off. Hank Johnson, Mercer’s trainer, is already eying top contender Michael Dokes. And Team Mercer – the fighter, Johnson, promoter Bob Arum, and manager Marc Roberts – is aiming for a late-1990 or early-1991 date with the champion. In fact, after Mercer’s very first pro bout in February, the post-fight questions didn’t concern the adjustment from the amateurs or his development or his added weight.

“What’s the timetable for a fight with Tyson?”

Mercer is 28 years old, so a two-year diet of low exposure four- and six-rounders wasn’t advisable. He’s already frozen his share of Mr. Softees, including Al Evans, who held an amateur victory over Tyson. But by 1990, the quality of opposition figures to dramatically increase.

At this point, the skeptics outnumber the believers.

“It’s the same predicament Tyrell Biggs was in,” says Riddick Bowe, Mercer’s former Olympic teammate and current rival. “The people who have him don’t have faith in him, so they want a return on their investment now.”

“The problem that had arisen in the heavyweight division is connected to economics,” says HBO’s Larry Merchant. “Anybody who says this kid is ready to fight Tyson by the end of 1990 is not interested in developing him to his fullest potential, so he can get his best shot at beating Tyson. It’s either short-sighted greed or their own conviction that if they take the longer and more deliberate road to the title, the fighter might get knocked off because he’s not really that good.”

Photo from The Ring archive

Is Mercer ready for the jump? At this point, he seems a one-dimensional fighter, but for a showdown with a champion like Tyson, his may be the right dimension.

“Being a puncher isn’t a negative,” said Johnson. “As long as he doesn’t go down to Georgia and Alabama for those punches, like Tyson does. In his first few fights, [Mercer] was going to Georgia, too. I’m trying to sharpen his punches up.”

Perhaps they can compromise on Kentucky.

Johnson, a former Army boxing coach, first worked with Mercer, a former Army sergeant, in 1985. Excited by Mercer’s natural punching power, the coach asked him back in ’86, and again in ’87, but Mercer opted to remain with his military unit in West Germany.

“In ’85 I didn’t know what to expect,” Mercer said. “I wasn’t too sure of myself. I liked to go to clubs, to party. You gotta be dedicated. No partying. I wasn’t ready to settle down. I said no (when they asked him back). The training was too rough. They thought I was kidding.

“In ’88, I knew from the first time what it took. I told myself I was ready. It was an Olympic year, and people said that if you put your mind to it, you can do anything.”

“When he came back in ’88, it was a different Ray Mercer,” said Johnson. “He had made up his mind he was going to give it everything he had. If he was as wild as he had been in ’85, we wouldn’t have had a chance.”

To earn a berth on the ’88 Olympic team, Mercer twice defeated highly-touted New Yorker Michael Bentt. He then kayoed all four of his opponents in Seoul, including South Korea’s Baik Hyun Man in the final bout, to win the gold medal in the heavyweight class. Despite the fighter’s lack of experience, Johnson wasn’t surprised by the success. In fact, before the Olympics, he and head coach Ken Adams had predicted their team would win six gold medals, with Mercer to be joined by Anthony Hembrick, Kennedy McKinney, Roy Jones, Andre Maynard and Michael Carbajal. (As it turned out, Mercer, McKinney, and Maynard did indeed win gold medals; Jones and Carbajal won silvers; Hembrick, the team captain and, along with Mercer, its leader, arrived late for his first bout and was disqualified.)

After the Games, the 6-foot-1 ½ Mercer immediately bulked up, scaling as high as 218 for a May kayo of Dave Hopkins, and setting in at about 211. Two of his first three foes, Jesse McGhee and Garing Lane, were chubby tubs of goo, but opponent number nine, former light heavyweight contender Arthel Lawhorne, who fell in two rounds, represented a small step forward.

“You look at Mercer, and then you look at what’s in the field, and if anything, we’ll have to hold him back,” said Johnson. “We need to fight a quality fighter, but as strong as he is now, I don’t think they’ll be able to go 10 rounds.”

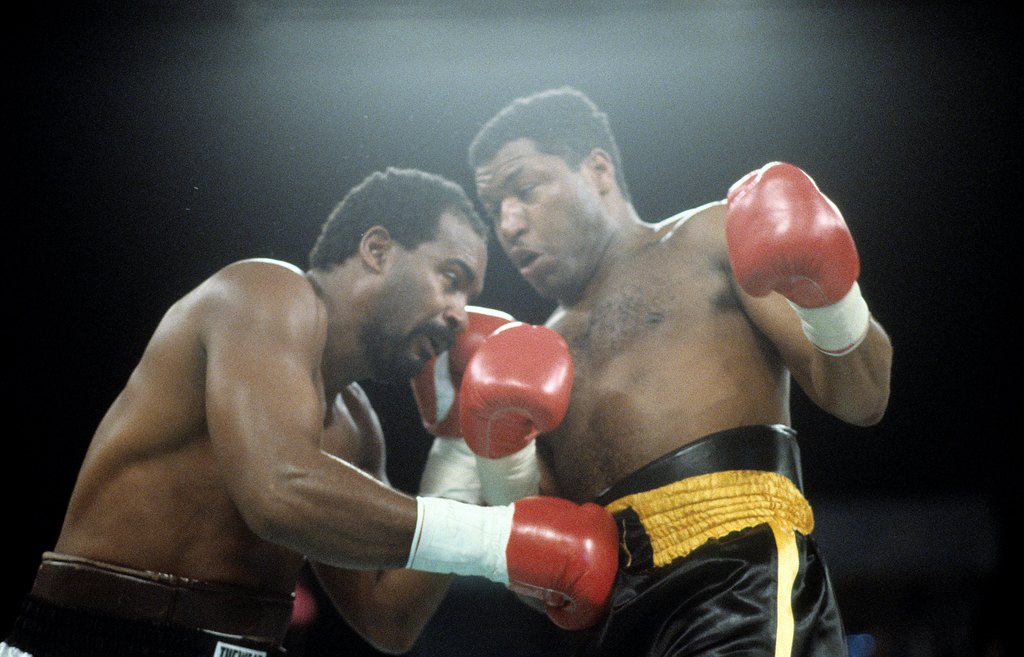

Mercer (right) lands a punch on Ossie Ocasio. Photo from The Ring archive

But perhaps it will be Mercer who won’t be able to go the distance. A heavyweight at his level has many questions to answer, and first-round kayos of marshmallow foes serve as nothing more than the obligatory introductory course to the pro game. Will his heavy muscles sag after six rounds? When pitted against a quick and clever boxer, will frustration replace elation? Can he sufficiently shorten his punches? What about his chin, which hasn’t yet been tested? And, finally, the ultimate question: Even if he should prove to be a legitimate title threat and a bonebreaker in the mold of a Mike Weaver or an Earnie Shavers, will he manage to topple a legend-in-the-making like Tyson?

Well, sooner or later someone’s got to do it. Whether it will be sooner or later is what will determine Ray Mercer’s future.

THE BOXER: “I’ll box him over 12 rounds. A lot of movement and he’s bewildered.”

I think about that more than anything. I don’t think about Lennox Lewis anymore. I find myself thinking about Tyson constantly. How to beat him. What is would take. How to elude him.

If I’m just lying there, I think about if a sidestep move will work, or if I hit him with a hook, how it would make him off-balance. I’ve talked to guys who have been in camp with him, and they tell me you’d be surprised at how easy it is to hit him.

Maybe we’ll take the fight back to Brownsville. The crowd would be split in half. We’d hype it as ‘The Brownsville Shootout.’ Maybe that wouldn’t be big enough. Perhaps Vegas or the Garden. The whole world would be watching. Riddick Bowe would come down from the dressing room and there’d be a big roar. Tyson comes down, his roar is not so big. The crowd behind me, that would help a lot.

Everyone’s waiting for one punch, the big bang, but it doesn’t happen, and it eventually slips away from him. After six rounds, he’s ordinary, and his stamina would betray him. A lot of movement and he’s bewildered. They’d announce the unanimous decision, and I’d go wild. I would just break.

Afterwards, I’d tell him not to worry because he won’t be unemployed. I’d hire him as my chief sparring partner. Maybe I’d even go $1,000 a week.

Photo from The Ring archive.

IT WAS JUNE 1988, and the Atlantic City Convention Center was filled in anticipation of the heavyweight title fight between Mike Tyson and Michael Spinks. Eddie Futch, the legendary trainer who instantly draws a mini-crowd at such events, was walking down a ringside aisle when he was approached by a 6-foot-5, 230-pound teenager.

“Do you know who I am?” asked then amateur heavyweight Riddick Bowe.

“Am I supposed to know who you are?” answered Futch. Bowe quickly shrunk from 6-foot-5 to 5-foot-5.

Neither Futch nor Bowe knew it at the time, but that seemingly innocent exchange helped spawn a close, and potentially productive, relationship.

A boy blessed with a man’s body, Bowe had been riding his reputation as a gifted heavyweight. But Futch, who had sparred with Joe Louis and trained Larry Holmes and Joe Frazier, was hardly impressed. In the subsequent months, when told of Bowe’s “attitude problems,” Futch was further turned off.

“I started hearing comments from fight people, all negative,” Futch said. “I saw one of his fights, and I saw a lot of potential, but also a lot of playfulness. He looked like he wasn’t really dedicated. He didn’t have that drive. That was my impression.”

When initially asked to work with Bowe after the Olympics, Futch declined. Then he was phoned by Rock Newman, the heavyweight’s manager. Newman detailed the conditions of not only Bowe’s career, but his life as well. The fact that his sister had been murdered; that his mother, who had borne 12 children, lived with the fighter in a rat-hole on a crack-infested block in Brownsville, Brooklyn; that ankle and hand injuries had severely reduced Bowe’s effectiveness before and during the Olympics. Newman sold his fighter, and Futch, who has always been supplied with a lot more fighters than he demands, bought him.

“There were a lot of handicaps,” Futch said. “Maybe he was worth looking at. I told him, ‘You have a lot of talent, but that’s not all it takes. You have to be single-minded in your intentions to go all the way.’ I told him, ‘I’m 78 years old and I don’t have time to waste. I have to make every day count.’ He was impressed by that.”

On a cold winter morning in Reno, Futch quickly tested Bowe by assigning him roadwork at dawn and indicating that he wouldn’t be able to see him off. Fifteen minutes after Bowe was to begin, Futch appeared and was happy to eye his fighter running in the distance.

“He’s passed every test,” Futch said. “His attitude is no longer a problem.”

Bowe with Eddie Futch. Photo from The Ring archive

Bowe is only 22. As a result, he’s not handicapped by the biological clock that ticks in the corner of his 28-year-old Olympic teammate, Ray Mercer. Futch and Newman have been able to set a pace that befits a raw prospect.

“What a fella’s as big as he is,” Futch said of Bowe, “people get the impression that he’s a man. But he’s just a kid.”

Perhaps manchild is a better word. Like Mike Tyson, who spent part of his childhood in Brownsville, Bowe was exposed to the harsh realities of street life at a ridiculously young age. At one point, Bowe and Tyson lived only three blocks apart.

“To a certain extent I can relate to him,” said Bowe. “I know what he went through as a child, and that motivates me. If he went through what he did and made it, why can’t I?”

Bowe remembers his first meeting with Tyson. It was in a park in Brooklyn a few weeks after Tyson had been beaten by Henry Tillman at the 1984 Olympic Trials. Bowe was running, and Tyson and two or three of his friends were sitting on a gate, watching him.

“One of them asked me if I was a fighter,” Bowe recalled. “I said, ‘Yeah,’ and they said, ‘Yeah, right.’ I kept running. His friend said something, and they all laughed.”

Five years later, Tyson is still watching Bowe run. Only now, Bowe is running toward Tyson, and not away from him. Futch has set a timetable of two years, or twice as long as Mercer. But he added, “[Bowe] could come along faster.”

“Ray Mercer said that if he fought me at this point, it would be a step backward,” Bowe said in October. “The only difference between me and Ray Mercer is that Mercer’s had nine fights and I’ve had eight.”

But there are other differences that are far less subtle. Where Mercer is a steamroller who will advance as far as his power takes him, Bowe is a classic standup boxer with a power jab (a Futch trademark), mobility, and a touch of class. He’s predictably been fed a steady diet of fall-down opposition, but in his most important bout, a CBS-televised second-round TKO of Lorenzo Canady, he was superb.

“I saw a complete chance in attitude,” said Gil Clancy, who analyzed the bout for CBS. “Before, his attitude was so bad, it was like the world owed him a living. In terms of talent, there’s no problem. He can box, he can punch. He might have more potential than any of them.”

But, of course, potential alone is never going to beat Tyson. Is Futch winning his battle to instill a sense of discipline? In his second bout, in April against Tracy Thomas, Bowe scaled 218. Less than a month later, in his third bout, against Garing Lane, he jumped up to an unflattering 230. And there are the physical disciplines as well. Futch points to Bowe’s tendency to overuse lateral movement, a leftover habit from the amateurs, and his reluctance to fire his surgically repaired right hand with full force. (When asked whether his chronically sore hands would negatively affect his ring future, Bowe said pessimistically, “I think so, but I hope not.”) A few fine Futch adjustments will have to be made before the gifted heavyweight becomes an accomplished one as well.

“I know how hard I’m working, and it’s disappointing that there are still some people who don’t believe in me,” Bowe said.

No matter. At the age of 78, Eddie Futch has decided that he has enough time for Bowe. And that alone should convince Bowe that he has enough time for Futch, too.

“Iron” Mike Tyson will be the subject of a forthcoming Special Edition of Ring Magazine. There’s no better time to subscribe to “The Bible of Boxing”

SUBSCRIBE NOW (CLICK HERE - JUST $1.99 PER MONTH) TO READ THE LATEST ISSUE