The Kid and the Champ: The Tale of Jorge Castro-John David Jackson

The word spread out quickly on the streets. The Champ was in town, coaching a young fighter from the big city at a local amateur card. Every gym rat and aspiring fighter in the entire city lined up at his locker room door, anxious to catch a glimpse of him. But The Kid just had to get closer than the rest. He needed to measure himself against the man everyone admired, the man he aspired to be one day. He had to show off.

He strolled right past the line and waltzed right into the locker room.

– Hey, champ! What’s up?

– Hey, get the hell out of here, you punk! You can’t just walk into my locker room!!

– What’s the matter with you? I just came in to say hi!

– Get lost!

– Yeah, you son of a bitch, YOU get lost! I will leave now but one day you’ll see me again, I will be just like you! Remember me!

The Champ turned his back on him. The Kid walked out, measuring the impact of his words, wondering how much it would take for him to deliver on his crazy promise, and what the consequences would be if he didn’t.

Right then and there, his own words began chasing him, walking right behind him. Those words, that look, this moment, the questions implied in this self-imposed challenge would haunt him for a long, long time. A countdown had begun.

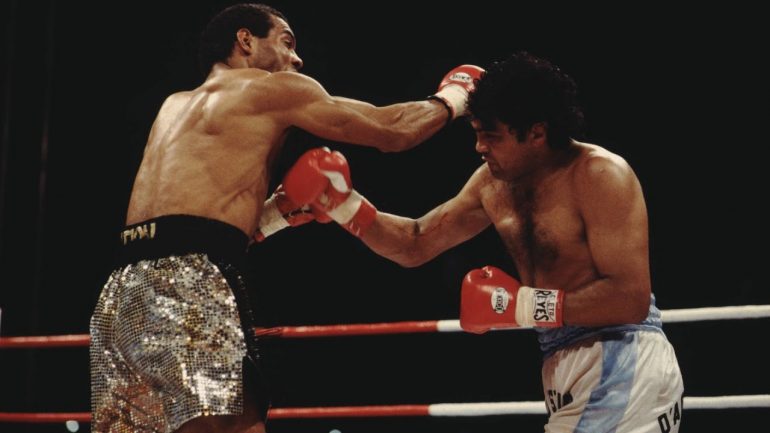

It was billed as just another title bout on a night of multiple title bouts.

The “Night of Champions” at the Estadio de Beisbol in Monterrey, Nuevo Leon, Mexico had no less than five championship fights scheduled for December 10, 1994, with Felix “Tito” Trinidad and local legend Julio César Chávez topping the bill in separate fights.

But buried in the televised undercard of this PPV broadcast was a fight with all the condiments for a historic matchup. It was a classic slick boxer vs. street brawler fight. A clash of graduates from the elite-level Kronk gym and the school of hard knocks. A grudge match for a title that had been taken away from one of them, who had earned it in the ring, and given to the other, who had grabbed it from a desk. Or so was the story.

But buried in the televised undercard of this PPV broadcast was a fight with all the condiments for a historic matchup. It was a classic slick boxer vs. street brawler fight. A clash of graduates from the elite-level Kronk gym and the school of hard knocks. A grudge match for a title that had been taken away from one of them, who had earned it in the ring, and given to the other, who had grabbed it from a desk. Or so was the story.

The disparity between the fighter’s records was also telling. John David Jackson, now the challenger for the title he had held until it was taken from him in a controversial political decision just a few months prior, was an impeccable 32-0, while titleholder Jorge Castro brought in an astounding 95-4-2 record, built on the back of a 128-bout amateur career.

The WBA title on the line had been stripped from Jackson after he failed to report a pedestrian non-title bout with that sanctioning body, an action that led to an ultimately fruitless lawsuit that embittered Jackson and set him on a revenge course that brought him to that ring in Mexico. There, Castro, who had grabbed the vacant title in a fight against Reggie Johnson in his native Argentina only four months earlier and had squeezed in a hometown defense against Alex Ramos barely a month before this fight, awaited him to ratify his long-sought status as a world titleholder following a failed bid against future hall-of-famer Terry Norris in 1992.

But for Castro, Jackson was just another fighter, another bump on the road on his way to bigger and better things.

“I never liked studying my opponents,” said Castro. “I just trained and got in the ring in the best possible shape. Today they watch videos and get scouting reports. Not me, I just asked how much money there was, and I got up there and fought.”

Training in Buenos Aires in his usual, throwback doghouse style, Castro hardly ever jogged or hit the speed bag or anything of the sort. He enjoyed doing as many as 15 rounds of sparring per session, oftentimes neglecting the use of non-human punching bags. This highly personal training method, along with his taste for fighting every month or more, afforded Castro a unique knowledge of the human psyche of his foes. Or so he claimed.

His next foe, however, couldn’t care less.

“I knew that Jorge was no match for me, boxing skills-wise,” said Jackson, after admitting that he had indeed studied Castro’s videos only to find nothing impressing or menacing about him. “I knew that he would be a tough opponent because even though he got hit a lot he was very durable. My expectation was to outbox him, but he was so easy to hit that I knew that I could beat him at his own game. I knew that he would underestimate my punching power.”

Always in shape, and a notable student of superstar trainers Emmanuel Steward and George Benton, Jackson chose to build up the only thing that can drain energy and power from a fighter before the fight, and that was his justified anger towards the sanctioning body that deprived him of his middleweight belt, the second one in his collection after the WBO junior middle trinket he had earned against Lupe Aquino in a vacant title bout back in 1988.

“I did let the fact that the WBA stripped me of my title unjustly make me angry,” said Jackson, who claims to have spent upwards of $125,000 in legal fees trying to get his belt back. “I beat them in U.S. federal court five times to prove that it was unjust, and they still refused to give me back my title”.

Even though Castro’s management team (headed by Luis Spada, who had an extra-cozy relationship with the WBA’s top brass) had clearly pulled all kinds of strings to get his fighter a hometown vacant title bout and an easy first defense, Castro’s involvement in this alleged sham was not too clear, but Jackson choose to blame him anyway.

“I was taking it out on him even though he had nothing to do with it. He had my title!,” said Jackson, who failed to see, before the fight, the consequences of harboring such feelings towards his opponent and allowing them to be mixed up in his ring performance.

If only he had heard the pre-fight analysis of the third man in the ring, the story may have been different.

“Castro was an experienced boxer at that stage with more than 100 pro bouts, so I knew he was always going to fight his way, advancing and taking no prisoners”, said Stanley Christodoulou, the referee appointed for this fight. “Jackson was a more cautious boxer, a skillful accumulator of points, not really a risk taker. But in saying that, I learned early in my career not to go into any bout with too many preconceived ideas about how it’s going to pan out.”

If there is a referee in the world who knows that anything can happen in fights between skillful American boxers and rough-and-tumble Argentine brawlers, it’s Christodoulou. A veteran of 69 title bouts going into this fight, the South African official had famously refereed the bloody clash between Argentina’s Victor Galindez and New Jersey’s Richie Kates, which took place in Johannesburg in 1976.

In what was then only his second title bout, Christodoulou allowed Galindez to continue fighting after a monumental clash of heads had opened a ghastly, T-shaped cut on his forehead that kept emanating blood. In every clinch, Galindez would wipe the blood off his face on the referee’s shirt, which was soaked in claret. The ending came only 15 seconds before the final bell, when Galindez (ahead on most scorecards, but risking a TKO loss if the fight had been stopped due to his injury) stopped Kates in what is still considered one the most heroic performances by an Argentine fighter ever.

Bonavena (left) in action against Floyd Patterson in February 1972. Photo from The Ring archive

There was a grim detail, however, that added to the legend of that extraordinary bout. Earlier in the day, thousands of miles from both Argentina and South Africa, former heavyweight contender Oscar “Ringo” Bonavena had been gunned down outside a brothel in Reno, and the news had already made headlines in his native country. But fortunately, Galindez, his former gym partner and long-time friend, was not made aware of Bonavena’s demise, and was kept from learning of it until after the fight. There were no shortage of fans and observers who believed that Bonavena’s spirit pushed Galindez beyond his natural resources to achieve a victory that would have been impossible under other circumstances, and, perhaps, under the watch of a different (or more experienced) referee.

Christodoulou, understandably, begs to differ.

“What I’m very proud of is that, under that pressure, I got the important calls right”, said the veteran ref. “I still maintain that to stop the fight because of Galindez’s cuts would have been incorrect. But as it transpired, Galindez could see, defend himself and kept going forward.”

Galindez did defend himself, turned the fight around, and perhaps inspired indeed by the recently departed spirit of his comrade, held on to his title belt while Christodoulou went on to become a part of Argentine boxing history, the magic man under whose watch the life expectancy of cuts within a fight is extended beyond any normal boundaries or limits, at least whenever an Argentine fighter is involved.

And he still keeps the proof of his rite of passage into this legendary status. “I still have the framed shirt I wore that night, still smeared with Galindez’s blood,” he claims. An entire nation still has it too, embedded in its collective memory along with Bonavena’s bullet-ridden shirt, as two gory symbols of a wild night rich in blood, sweat, tears and glory.

But as the bell rang to start the Castro-Jackson title bout, new memories were going to be built upon those old lingering recollections of Argentina’s most epic bout. And for that to happen, new and extraordinary things would need to transpire.

In this case, both fighters seemed to inexplicably diverge from their natural paths to end up trying new strategies that yielded very different results for them.

“I don’t know what happened to me. Because I was never before the kind of guy that fought Jackson that night,” said Castro. “I was a guy who enjoyed going in and throwing a lot of punches, but in that fight he beat the shit out of me. Lefties were always difficult for me. He always landed before I could throw a punch. He didn’t punch hard, he had hands of cotton, but he threw and landed a lot of punches, and that caused my eye to swell and then to cut. He had much longer arms, he could reach me very easily. I could never reach him. He was incredibly long. I was always short. That’s why I could punch him only when he came in close. I was never able to hit him.”

As Castro lost his compass and his strategy, Jackson seemed poised to use a different approach too.

“I knew that I was going to be the first man to stop him,” said Jackson, thinking perhaps that he had a chance to succeed where both Norris and Roy Jones Jr. had failed. “My main and really only priority was to win back my WBA title. The ass whipping (and) the boxing lesson just came along with it.”

Unaware of Jackson’s anger towards the WBA, Castro was his usually aggressive self during the first stretch of the bout, where he managed to stop Jackson cold in his tracks on a few occasions and then had his gesture reciprocated by the lightning-fast former two-weight titleholder.

The real fight, however, started shaping up after the fifth round, when the relentless punishment dished out by both of them began to take its toll.

“I believe in the fifth or sixth round he hit me with his best shot,” said Jackson. “A left hook that landed clean on my chin and shook me from head my head to my toes and I went nowhere. I even fired right back. If he knew nothing else, he knew that he was in for a fight. Now he tells everyone that I had no power, (but) look at his face.”

For Castro, who still contends that Jackson’s punching power didn’t affect him, the real danger was brewing in a pair of severe bruises and cuts, one of them inside his mouth. But it was the swelling on his left eye that turned the fight around for him.

“In the sixth I felt the explosion,” said Castro. “I felt the swelling on my left eye exploding, and the blood stated pouring out. The inflammation just exploded, and I felt the relief, but there was a spurt of blood inside my eye, and the cut was opened much more. I couldn’t see anymore, that’s when I started wiping my eye on the referee’s shirt.”

Initially, Christodoulou failed to acknowledge the similarities. But it didn’t take long for him to change his mind.

“To be honest, I never thought of a parallel between the two bouts until afterwards, even with Castro wiping his blood on my shirtsleeve as Galindez had done 18 years before,” said Christodoulou. “During the Castro-Jackson fight I was fully concentrating on that ring in Monterrey, on Castro’s cuts, on his condition, on what was happening in front of me. But yes, once it was all over, I thought to myself ‘Another dramatic Argentine victory.’”

As it turns out, the similarities with that fateful night in Johannesburg would not end there.

In fact, they were just beginning.

The Champ knew that his fellow fighters would answer the call.

After all, who’s more sympathetic to the solitude and grief of a crushing defeat? Who would understand him better in this time of tribulation? Who but his fellow boxers would be more willing to hear all about the slings and arrows of the outrageous fortune that befell him?

Unbeknownst to the Champ, one of the young fighters who sat across the table from him during one of these visits had a story to tell. He wanted to tell him about his many fights, about his failed recent excursion abroad in which he held his own against a fearsome champion in an honorable defeat, about his still-enormous promise as a future world-class boxer. But he also had something else to say, a tale he had been keeping in his chest since his earliest days as an aspiring prizefighter.

If boxing had taught the Kid something, however, it was patience. And patiently he waited until the right moment finally materialized.

-Hey, Champ… remember that time when some snotty kid walked into your locker room and you kicked him out? Amateur card, small town, middle of nowhere, about 10 years ago?

– Yeah, I remember that. Was it you?

The Kid hid a wide grin behind a carefully rehearsed wink, capped by a cocky smile with the corner of his mouth.

-Well, I am happy for you, Kid. I really am.

Right then and there, the Champ’s words stopped chasing him. Right at that moment, in only the second time ever in his life in which he was facing the man that he admired and hoped to emulate, the Champ’s words stopped haunting him. A new countdown, however, had also begun.

By the end of the eighth round, blood was everywhere.

It was all over Castro’s face, squirting in every which way. It was on Jackson’s body. It was on the canvas and on the ropes. And it was, once again, soaking Stanley Christodoulou’s shirt, in a gory déjà vu of the fabled Galindez-Kates bloodbath.

Soon enough, Castro’s blood was also being wiped away by the ringside physician in his corner, during a check-up in which he was deemed unable to continue.

But just as Tito Lectoure had pleaded 18 years ago with Christodoulou to allow Galindez to continue fighting Kates in spite of his horrific cut, now Castro’s corner man and manager Luis Spada requested the doctor to give his charge one more chance. “Please, doc,” Spada is overhead saying, “give him the ‘champion’s round’”.

The bell rang to begin the ninth, and with it also began the live filming of a three-minute unedited highlight reel that still lives on as proof that art does indeed imitates life.

That is, if you consider the entire “Rocky” franchise a work of art (which we totally do).

It was, for a moment, dangerously close to never happening. After two minutes of a relentless, two-fisted shellacking, Jackson was still on the attack while Castro struggled, missing most of his punches widely, blinded by the blood pouring from his cuts.

Christodoulou was ready to intervene, and in the end, he had to. Just not in the way he had anticipated.

As the veteran South African referee was moving in to call it a day, night fell upon Jackson as Castro connected with a flush left hook to his chin to turn his lights out with a single punch.

And right there, just as Jackson fell backwards to the canvas as if struck by the wrath of hell, Castro, just like another Argentine contesting a world title on Mexican soil some eight years earlier, realized that he too had unleashed the fabled “Hand of God” that turned defeat into career-defining victory. During the 1986 World Cup quarterfinal match against England at the Estadio Azteca, all-time soccer great Diego Maradona scored what turned out to be a decisive goal with his right hand (an illegal move that also included a decoy maneuver, an act of deceit, and the unwilling complicity of a referee with a momentarily uninformed vantage).

A hand that, much like Maradona’s, would be remembered and discussed for ages.

The play-by-play, inch-by-inch slow-motion replay of Castro’s knockout is worth exploring in detail.

Blinded by his own blood, ostensibly hurt and on the verge of being stopped, Castro realized he needed a bold move to stay alive. His best card, as it turned out, was to “play dead.”

“I saw him absorbing blows like a punching bag and slumping back against the ropes,” said Christodoulou. “I heard the talk that he was trying to lure his opponent in by faking his condition. But from my close up viewpoint he appeared to be a struggling boxer, one who could hit the canvas at any moment. If Jorge now contends that he wasn’t hurt, I accept that. But what I did see was a fighter who took a lot of punishment bravely refusing to back off.”

Jackson certainly doesn’t buy into the “hurt fighter” tactic.

“Well, he didn’t put himself on the ropes like he said he did, because he had a little help from me,” chuckles Jackson, still bitter after all these years. “If you watch the video again you will see that he rarely hit me at all, he missed most of those punches that he threw. I couldn’t take notes of his ‘tactical move.’ I was too busy showing Jorge that he was their token champion because Reggie Johnson outboxed him for my title and they still gave it to Jorge.”

Being the sole protagonist with unrestricted access into his own mind, Castro insists on the fact that his own account of the entire sequence is the only true version of the events in question.

“In the ninth round, when he landed that hand, I made him believe I was hurt,” said Castro. “But he fell right into my trap. I started covering myself until I could throw my right hand to knock him out. But I ended up catching him with my left. The one I threw with my full power was my right. What happens is, and most fighters don’t know this, whenever you throw a right hand, or any combination, you always finish with your left hand. That’s how it was. I was not hurt, I simply played the part just to lure him to the ropes. I used to do that all the time. I did it against (Miguel Angel “Puma”) Arroyo too. He came to finish me, I hit him with a right-hand volley and hurt him. And when I had someone hurt, he never escaped. And that’s what happened with Jackson.”

And it happened not a second too soon.

“In that ninth round, I remember thinking that I would stop the fight if Jackson landed one more good shot,” said Christodoulou. ”No sooner had the thought run through my mind when Castro landed the sweetest of left hooks right on the button. I imagine Jackson surprised everyone when he beat the count, but I checked his condition, saw that his neck muscles were still fine, he responded readily when I asked him to lift his gloves, so I ruled the fight to continue”.

And it did, but not for too long. With Castro hovering near the fallen Jackson, the Argentine was all over his foe as soon as he got up from that first knockdown. He proceeded to send him to the canvas twice more to finally force the stoppage.

“In one of the TV broadcasts, one of the guys says ‘all that can save Castro right now is a knockout’… and right then I scored the knockout! ,” said Castro. “When Jackson fell (for the first time), the referee sent me to the neutral corner. On the second one, the same thing. But as soon as he waved the fight back on the third time, I was right behind the referee. And I unloaded on Jackson. At that moment, my brother was screaming ‘Jorge, there are 30 seconds left.’ When I landed that hook, it landed right on the chin, and he crashed right by Christodoulou.”

The video of the fight also shows Castro’s cornermen assembled, already on the ring, right by their corner, and one of them is holding a towel in his hand. Was a self-imposed stoppage ever a possibility?

“I always told them ‘if you throw the towel on me, I get off the ring and knock you out!!,’ laughs Castro. “They never did that. I was either knocked out or lost on points, but I would’ve never allowed a towel.”

Jackson, of course, can only recall the heartbreak of a missed opportunity.

“I was about to stop him, but guess what? I forgot to duck,” he laughs, sarcastically. “He was hurt. Look at when he threw the left hook, it was more instinct of a punch than a well-timed shot. He wasn’t even really looking at me when he threw the shot, but on the other hand I didn’t see his shot when it landed, and those are the punches that have the most effect; the ones that you don’t see coming. I should have ducked like I usually did, but I didn’t, and I paid the price.”

Jackson (pictured left with Sergey Kovalev) has gone on to become a world-class trainer. Photo courtesy of Main Events

For Jackson, “the price” was as steep as they come. Lucrative bouts against Roy Jones Jr. and Felix Trinidad disappeared in the air. And by the sound of it, he never did quite recover from the heartbreak of losing a fight that he was only seconds away from winning.

And yet, he still claims that his biggest heartbreak came before the fight even started.

“Taking my title hurt me more than losing the fight,” said Jackson, now a world-renowned trainer in his own right, working with some of the best talents in boxing. “Taking my title took the food off my family’s table, taking my title took all that away, and that was my life, being a champion. With no title I had no more leverage in boxing. My next fight was in the discussion stages with Roy Jones for a couple million, but I think Roy was set on moving up and facing (super middleweight titleholder) James Toney anyway.”

For Castro, on the other hand, it was the beginning of a new life, a measure of success that he had failed to reach in the previous 101 professional fights, and which turned him into a celebrity in his native Argentina, where he would go on to participate in talk shows, reality shows and more, securing the love of his people in that process, a mutual love affair that still stands today.

“When I came back home there were 20 miles of cars lined up waiting for me. That was unforgettable. Thanks to that fight and to all of the things I did, I remain in the memory of my people,” said Castro.

“That fight will remain in my memory for all my life. I will be dead, and the fight will still be remembered. It was just like a Rocky movie, but mine was true and the other one was fiction.”

And just like in the Rocky franchise, this fight did have a rematch, which took place in Cipoletti, Argentina, in February 1998. Castro won again, this time on points and with no title at stake. A rubber match was discussed, but never transpired.

It would not be the only ‘third chance’ that failed to materialize in this saga.

The hours that passed between Bonavena’s death to Galindez’s miraculous victory on May 22, 1976 were only a handful. For religious, mystic and esoteric types, the belief in any kind of metaphysical connection between the two events can be quite real.

One more name is needed, perhaps, to make sense of this entire invisible chain of mutually inspiring events, and to bring closure to this story.

On January 8, 1995, barely a month after the Castro-Jackson fight, middleweight legend and former WBA-WBC unified champ Carlos Monzon died while on a furlough from his prison sentence for the manslaughter of his common law wife.

Carlos Monzon. Photo by AFP/AFP/Getty Images

In a final act of their sparse, lifelong love-hate spiritual connection, Monzon, the “Champ,” passed away just after seeing Castro, the “Kid” that barged into his locker room in 1983 and who later visited him in prison in 1992, deliver on his childhood promise of walking in his footsteps and reaching at least a portion of his glory. Monzon saw Castro defend his old WBA title in a memorable fight worthy of being named The Ring’s Fight of the Year, just as Monzon’s title-winning effort against Nino Benvenuti was in 1970.

Life didn’t give them the chance of a third meeting. As fate would have it, other chances were afforded to them in this process: the chance of inspiring each other (knowingly or not) to find a way to inscribe their names in history with only the minimum amount of personal interaction – as well as a larger amount of ‘something that the word randomness fails to describe’, as the poet Jorge Luis Borges would put it.

At least one of the protagonists of this story is convinced that in Castro-Jackson, just as in Galindez-Kates, greater powers seized the opportunity to show their hands.

“I have no doubt that Jorge felt a spiritual sense of purpose in that fight,” said Christodoulou, a self-described man of faith. “I’ve seen so many inspiring, against-the-odds victories in the ring, wins that transform boxers and their lives. It’s not difficult to recognize how a spiritual purpose could inspire a fighter. Equally I’ve seen many a boxer crushed in defeat.”

“My faith is central to my life, but in the boxing ring, I’m always reminded of the two boxers who both pray to God to deliver them victory. Which one does God favor? The one with the best hook”.

For a fleeting minute on a boxing ring in Monterrey in 1994, the hand of God decided that, as much as His love may shine on all of His creation, the best hook belonged to the “Kid” that promised to give his childhood hero a run for his money.

If that’s not a testimony of the existence of the “Hand of God”, then I don’t know what is.

SUBSCRIBE NOW (CLICK HERE - JUST $1.99 PER MONTH) TO READ THE LATEST ISSUE