There’s no shortage of people who say promoter Greg Cohen did them wrong

Boxing promoter Greg Cohen, a boxing lifer based in New Jersey who has managed to stay in the game and accumulate his share of successes, helping steer talents like Hasim Rahman, is now doing some fighting himself against a spate of criminal charges and civil charges.

The fight game deal-maker, who owns a healthy-sized roster signed to Greg Cohen Promotions, notably of late the now former middleweight titlist Rob Brant, was arrested, charged and convicted of wire fraud.

Cohen, age 50, of Livingston, N.J., has been sentenced and will serve six months in prison for the infraction.

The news ricocheted around the fight game sphere on Saturday, Nov. 23. Many wondered how such a story had been kept quiet, and speculated as to why that was so. Those who took the greatest interest in the development, for them, it wouldn’t be categorized as a jaw-dropping surprise. No, Cohen was never in the King-Arum-Oscar-Eddie realm as a promoter, but he was a grinder, he had a knack for snagging foreign talent, and under radar types who often could be placed as viable challngers, B side types, against world class foes. But people heard stories….

The writer spoke to Cohen for a March 2015 story which ran on the RING website:

“The promoter learned his craft under the late Cedric Kushner, he told me, and started in boxing around 1989. His cousin Marc Roberts managed solid hitters like Ray Mercer, Charles Murray and Al Cole, so Cohen saw how things were handled on big stages. “Me and Cedric had a long run together, I loved Cedric, he was a dear friend who taught me the promotion business.” Cohen has done other things, and did well with boxing as a side-line, of sorts, though the last six or so years it’s been all boxing. He had Hasim Rahman when Rock upset Lennox Lewis. He was with Shannon Briggs for most of his career, with Roberts, and with Kushner, did deals with Shane Mosley and Joel Casamayor. Austin Trout was his most recent champion, the promoter said.”

As with someone who has built up a stable of fighters, and infrastructure to maintain a business, there are ripples to consider. The writer reached out to ask how Cohen would structure business in his absence, but no reply had been furnished at press time. Cohen loyalists have pushed back, mostly on social media, with the assertion that the wire fraud case has nothing to do with boxing, or people in the boxing sphere.

The name of the person who reported to authorities that he had been done wrong by Cohen isn’t public. The case played out in the Southern District of New York very quietly, because Cohen’s arrest and none of the subsequent legal developments made the news, until he got sentenced.

Some of the fighters spoken to admitted they were happy the wheels of justice advanced, on Cohen.

But the gist is this; Cohen received $200,000 from a man, because he promised that chunk of money would be invested with a money manager in some stock that would bring a gargantuan return. The money was handed to Cohen, but no home-run investment was ever made, and the mark got worried when the promised results weren’t accomplished. He went to law enforcement, after dealing with Cohen starting in April 2016, and an investigation kicked in, at the end of 2017.

Ryan O’Hara of FightNights broke the story of the Cohen wire fraud conviction and Sean Nam of Boxing Junkie gave more details of the specifics. Cohen was sentenced last week in the the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York to six months in prison, three years supervised release and 150 hours of community service on one count of defrauding an individual by means of false pretenses, a federal offense.

Cohen was arrested on Jan. 10, 2019 but released on bail, journalist Nam found. A text and call from this writer to Cohen to verify reports which have come out, including one on Boxing Scene which referred to the sum of money the aggrieved party sought to recover as a “loan,” were, again, not returned.

We also wanted to ask for verification that the money was paid back, with interest, as the Boxing Scene story announced.

The criminal complaint text offers some insight into how Cohen, who told the victim that he’d be investing $450,000 in the deal, allegedly tried to explain away when things didn’t unfold as he’d promised. The complainant asked Cohen, who told the guy he’d done this sort of private placement stock purchase 80 times, where the money was, where the profits to what he’d been told was a deal to purchase stock from a company before their stock was made available to the public, the New Jersey resident had an excuse.

The victim had started making calls, and sought to speak to the money manager who’d be exercising the private placement deal. He determined that the manager was in fact not aware of this supposed transaction. The money manager informed a firm attorney, and that attorney sought to question Cohen. Cohen soon after contacted the complainant, who asked where his money was.

Can’t talk, Cohen emailed, because I am “in the hospital awaiting surgery.” Two days later, Cohen emailed that he was still hospitalized, and “on pretty large doses of morphine.” Four days later, Cohen said he was having complications from the surgery. Soon after, law enforcement decided to arrest Cohen for fraud.

Cohen has promoted fights all over, and placed his fighters in overseas scraps. Boxing is known as the red-light district of the sports world, but rules and regulations are in place and sometimes enforced. Would Cohen be able to exit prison and, say, promote a boxing show in New York? (Disclosure: I helped call a show co-promoted by Cohen, which was supposed to feature Zab Judah, who was scratched from the main event for having a fight at the weigh in. To my recollection, I was paid for the duties performed in timely fashion for that 2015 event.) A spokesperson for the New York State Athletic Commission offered this statement when I inquired about the right to promote a boxing show, for someone convicted of a felony. The commission was informed my query pertained to the Cohen situation.

“The New York State Athletic Commission is investigating the matter regarding Greg Cohen and is reviewing the record and conviction. The Commission cannot comment on the pending investigation,” read the NYSAC statement. Per NYS law, a conviction is not an automatic bar to obtaining a license to promote. The New York State Athletic Commission may, consistent with the provisions of the Correction Law and Executive Law, deny, suspend, or revoke a license following a conviction where the applicant or license holder demonstrates the licensee: 1) failed to maintain a satisfactory record of integrity or 2) engaged in fraud or fraudulent practices.

From the About section on the GCP website: “From the first day, Greg Cohen’s boxing life has been about taking risks, spotting opportunity and drawing new lines where he wants them, not staying inside the ones that are already there.”

And regarding his practices; RING spoke to some fighters who do not look back fondly at their time under the GCP umbrella.

Fighter Tony Luis, a Canada based pugilist fighting as a super lightweight, has a bad taste left in his mouth from a stint with Cohen. He said that Cohen was his promoter for four years, and still owes him money from his last fight with the N.J. business-man. “That was versus Samuel Amoako on CBS back in February 2016,” Luis said. “He also failed to provide me proper documentation for me to file my income tax return for that fight. Continuous phone calls, emails and voicemails from my accountant that came and went with no response. He was also late on some of my pay with the Derry Mathews fight in 2015. Weeks went by and I had to threaten legal action. He also tried to gyp me on the Cdn/US exchange.”

Luis was happy to part ways with the just-sentenced promoter. “There was a six month extension clause he tried to enforce. But I fought it. He was in breach on a few other things. He was in violation of some things on the Ali reform act. Once we hit him with that in writing from an American lawyer he backed off.”

Asked for his thoughts on the news that Cohen is going to do time for wire fraud, Luis summed it up succintly: “Karma,” the 31 year old athlete answered.

Ex super welterweight champion Austin Trout said he was promoted by Cohen for two years, and he too doesn’t look back on that spell with fondness. Yes, he told me, he heard the news that Cohen got pinched for wire fraud, for promising a mark a guaranteed return, and then didn’t deliver. He was not displeased.

Boxer Trout had to fight in the ring to rise in the ranks, and outside the ring, to get Cohen to pay him what was promised.

“He was my promoter for two years,” the 34 year old Trout said. “We technically ended on bad terms,” he continued, and he said that Cohen forged his signature on a contract extension. And Trout in fact filed a suit versus Cohen, in 2013, claiming that Cohen got in the way of Trout potentially appearing on the pay-per-view undercard to Floyd Mayweather’s fight with Canelo Alvarez. Trout maintained that Cohen was acting as his rep, even though he understood their contract to be finished. Trout was in the mix for a fight on Showtime, but the cable company steered away, the boxer said, because Cohen told them he’d take them to court if they proceeded without him attached. And did that case move to a disposition? Trout said adviser Al Haymon recommended he settle with Cohen. “Instead of suing him, I had to pay him to go away,” Trout recalls.

Texas based light heavyweight Samuel Clarkson says he finally got Cohen to pay him fully for his April 2017 fight against Dmitry Bivol, which Bivol won by knockout in round four, two years later. Clarkson, along with promoter Ronson Frank, had to resort to the legal system to get compensation for the bout which unfolded in Maryland, promoted by Banner Promotions and GCP. Cohen was on the hook for the Clarkson purse. Cohen employee Sarah Fina took to Twitter and posted legal docs, and the all-caps note PAID IN FULL Nov. 23, as she defended the promoter. The doc, dated April 1, 2019, is marked GENERAL RELEASE, and indicates Cohen paid Clarkson and Frank $30,000, to satisfy contractual terms from the fight two years before.

There are other folks who have done business with Cohen, and have no complaints to share. Minnesota promoter Cory Rapacz co-promoted with Cohen a bunch of times, including a August 9, 2019 show at Grand Casino, in Hinckley, MN, which featured names not known to the masses. How was it working with Cohen? “No different than working with anyone else I guess,” Rapacz said. There were no negative interactions in business matters with Cohen, then? “Nothing that comes to mind,” Rapcacz said. The Minnesota fight game player in fact has agreed to co-promoter deals with Cohen with talent like Minnesota native, the middleweight Rob Brant, ex WBA titlist, and featherweight prospect Ramiro Hernandez, from Ohio.

TV prouducer Nelson Sweglar, a VP at World Wrestling Entertainment for 15 years, who also did work for ESPN, has been producing boxing for a long spell. He did so for Cedric Kushner, the NY-based South African who hit a few jackpots with name fighters, including Rahman, when the Baltimore boxer upset Lennox Lewis. Sweglar met Cohen when Greg was working with Kushner, around 2003 or 2004. He shared that he then went on to produce content for Greg Cohen Promotions all around the nation. That included a June 26, 2015 show topped by a Dennis Hogan-Kenny Abril super welterweight title fight in Niagara Falls, NY. Tony Luis appeared on the card, as did Jarrell “Big Baby” Miller, then 13-0-1. He was co- promoted by Cohen and Dmitriy Salita.

“That payday never did happen,” relayed Sweglar. He headed up the production for a slate that appeared on CBS Sports Network, on cable, part of a fertile term for Cohen, as it was one of seven shows he promoted or co promoted in that year. “That never did get resolved, but would I start litigation? That’s counter productive,” Sweglar said. “It’s a strange business, working as freelance employees, the relationship is not as straight forward or as solid if we were 9 to 5. But of all the stuff I’ve done with Cohen there was only that one incident. In all honesty there were a lot more shoots when the payday was there.”

Others have decided to not write off the loss. Linacre Media, headed up by Mark Fratto, didn’t find working with Cohen to be as smooth a ride.

TV producer and sometimes ring emcee Fratto is one of many who had to lawyer up to get Cohen to pay up.

Cohen was late in paying production costs to Linacre for two shows, and then the promoter wanted to hire Linacre for a Nov. 11, 2016 show in WinnaVegas Casino, in Iowa, so a request for 2/3 up front money was made. The last third, $16,000 plus, it took about 16 months for that to make its way from Cohen to Linacre’s account, and that came about when Fratto went the legal route. A filing in May 2018 shows that the NY State Supreme Court’s records indicated Fratto won a judgement against Cohen. Indeed, Cohen paid up before the judgement deadline, and a record of satisfaction was then furnished by Fratto. (Note: Fratto is the architect of the Facebook Fightnight Live series, and the writer performs blow by blow duties on the FNL shows.)

Keith Veltre of Arizona does the day to day labor for Roy Jones Jr Promotions; that entity and Greg Cohen partnered up at the beginning of 2016. “I could not be happier about teaming up with such a first-rate promotional outfit as Roy Jones Jr Boxing and their team to present 12-15 outstanding boxing shows in the next 12 months,” said Cohen in a release. “We’ve had great success with last year’s CBS Sports Network shows, but the addition of such a world-renowned name as Roy Jones adds a strong element of greatness to each presentation. And the addition of the RJJ stable of fighters makes the possibility for several exciting match-ups. I am proud to be affiliated with CBS Sports Network and especially my close business associates at RJJ.”

This January 2016 marriage ended up in divorce, and court.

The buzz wore off, though. Veltre ended up going to court, and in Sept. 2017, a judge rendered a decision on a dispute. Cohen was to repay $50,000 to Veltre, at $5,000 a month for ten months, starting in December 2016. That monthly arrangement didn’t hold, though. “In the end we had to serve TD Bank the judgement,” said Veltre, “and they froze his bank account and the judgement was fulfilled.”

Cohen has other disturbances to wrangle, beyond the wire fraud deal. A Long Island man, Cliff Mass, has lodged a civil suit against Cohen, alleging the boxing promoter enticed him to invest in GCP, to the tune of around $250,000, and offered paid employment as well. The fat lump sum was used to help buy time to place fights on the CBS Sports Network, it is alleged. Mass did work for Cohen, and became concerned when the promoter didn’t pay the promised weekly allotment. The promised returns, from boxing events, were not paid out as he’d been promised, either. And, for most of his time inside the Cohen sphere, he heard excuses. Bank issues, wires sent to the wrong account number, and there were promises. Next big fight, you’ll get caught up. Then, explanations, a declaration that the show lost money. Finally, the Long Islander had enough, and retained a lawyer. The suit wove its way through the system, from March 2018, to now–and a settlement date, between Cohen and the civil suit filer, is set for early December.

Inside the boxing scene, which is mostly a fraternity, still, though inroads have been made to lessen the “boys club” element, tales of Cohen’s spotty payment record have been bouncing around for awhile. One might think that such practices would be aired out publicly, and such a pattern would be arrested. Because, most if not all agree, people who put their life on the line for their paycheck deserve the ultimate in decency and fairness regarding compensation. But people we spoke to admitted feeling bashful that they went through ordeals, and some wouldn’t go on the record, not wishing to prolong the negative experience. We asked fighters like Malik Hawkins, a plaintiff versus Cohen in a June 2018 suit, Ismael Barroso and Travis Kauffman to share their experience of being promoted by Cohen, good or bad. No reply, but for Kauffman, who offered a no comment. RING sought clarity from the heavyweight contender Miller, about his deal and relationship with Cohen, and had not heard back at press time.

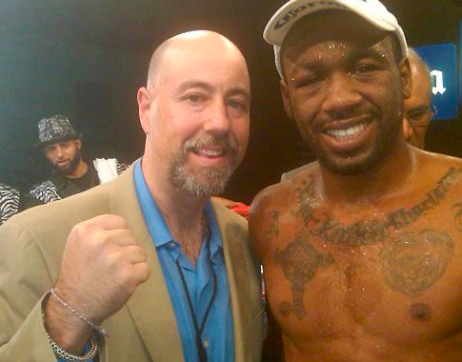

Cohen listens as Miller breaks down a win on Showtime, with Steve Farhood.

We also didn’t hear back from more people who went the legal route to hash out payment issues with Cohen, like fighter Lateef Kayode, who filed suit versus the man who promoted him, in January 2016. Many of the people who did choose to process this situation with RING are wondering if there are other shoes to drop, or if this prison stint will be the end of A darkly dramatic chapter for the New Jersey man.

One person who has done business with the promoter wondered aloud if the authorities would extend so much time, energy and funding on a lengthy investigation, with the end result being only a six month lockup for the focus of the examination. On the grapevine, which is ever laden with clusters of chatter and gossip and such, people are hearing that Cohen is saying he will be back in the game, in boxing promotion, next year, ready to rumble again after being stopped out by the authorities. A technical knockout, in his mind, not a career ending, catastrophic knockout. A comeback story, like “Rocky,” only not so much.