The boxing ring prepared Joe Murray for life in the courtroom

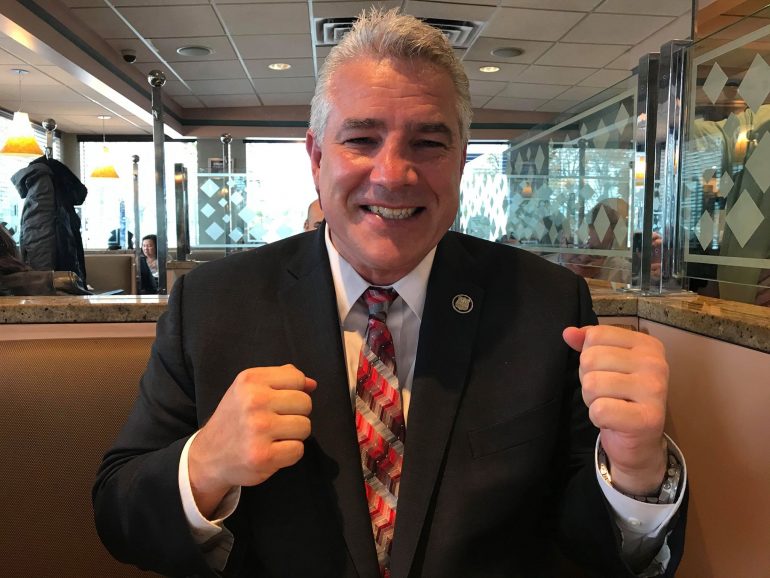

Upon meeting Joe Murray for the first time, it’s unlikely to surprise you that he had been a boxer in years past. The 52-year-old from the Kew Gardens section of Queens is tall with broad shoulders built for delivering hooks and crosses. His hands are like mallets, and he has a fighter’s nose, slightly twisted to the right, the product of a sparring session at Gleason’s Gym when a local pro knocked it so askew he could see it in front of him.

Murray has brought that fighting spirit to the courtroom as a trial lawyer, which he says is the closest adrenaline rush to being a boxer.

“It is the only thing that comes close to the thrill of when you’re in the ring. When you’re slugging it out and the referee’s there, and then the announcer says ‘In the blue corner!,’ that’s what it is to try a case,” said Murray.

Cross examining a witness, he says, is like putting pressure on an opponent to test their stamina. When something bad comes out in evidence, a defense attorney has to keep a poker face, like when a boxer hides the fact he’s hurt after a devastating punch lands.

“These skills translate,” Murray says.

It’s Tuesday at noon, Election Day across the country, as Murray takes his lunch break at Blue Bay Diner in Bayside, Queens. A registered Democrat, he’s running on the Republican ticket for District Attorney of Queens, an uphill battle if ever there was one in electoral politics. Queens is one of the most liberal regions of the one of the bluest states in the country. He’s running against Melinda Katz, the Queens borough president in her second term, who has raised more than five times the funds he has in his truncated, ten week campaign.

He says he was compelled to jump in the race due to progressive policies which had risen from the tightly contested primary battle on the Democratic side. He objects to the idea of abolishing cash bail, and says low-level crimes like subway fare evasion should be prosecuted as a deterrent.

“All these people complaining, ‘I don’t have the $2.75 to pay the fare,’ but they’re holding up $1,000 iPhones as they’re filming the police officers,” says Murray, as he shows off his older model smartphone with a cracked screen.

One of his ideas for bridging the gap between the community and police is to fund boxing programs with the millions of dollars from federal asset forfeitures held by the Queens DA office, and he’s open to having voluntary boxing training as an alternative to community service sentences.

“We’re praying for rain,” he admits, as he looks out the window, spreading butter on his toasted blueberry muffin. Low turnout in a low profile election cycle, he hopes, can carry him to an upset victory.

That’s not to say Murray has ever run from a fight. At age 20 he became a police officer, and picked up boxing at age 24 while training at the Boys Club of New York on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. He had about 25 amateur fights, competing in three New York Golden Gloves tournaments during the mid-90s. He made it to the finals of the 1995 NYC Metros as a heavyweight, facing future contender Monte Barrett.

“After I woke up, I was like, ‘What happened? Did the fight start?,’” said Murray with a laugh.

The two became close friends, and Barrett, who, like Murray, also played football at John Adams High School in Ozone Park, helped him campaign.

“He’s a nuts and guts guy, he got in there with me and gave his best,” said Barrett, who fought twice for heavyweight belts in 2005 and 2006. “That’s what we need in office, a person who knows on both ends what it’s like to get knocked down and get back up and fight even harder.”

He traveled the world as a boxer, representing the NYPD at the World Police and Fire Games in 1991 and 1993. By his third fight he was competing in England, the first of four trips there, and traveled to Belfast to box against a member of the Royal Ulster Constabulary.

“Second round I go out there, I’m rocking him, the ref jumps in and gives him a standing eight count. As soon as he’s done counting eight, he takes a point away from me, said I hit him late when he tried to break us up,” remembers Murray. He lost a decision, and the crowd booed, but he says the crowd was happy when he was named Fighter of the Night. “I could not buy a drink in Ireland after that,” said Murray.

Murray considered turning pro, but he had other matters to tend to first. Murray was charged with felony assault after an altercation with a fellow officer on the job, breaking his jaw with a punch.

“I went to go talk to this detective because he handcuffed my friend and slapped him around,” said Murray. “Then he made the mistake of trying to do that to me.”

Murray eventually beat the criminal charges when a jury declined to indict him. He later plead no contest to the department charges without having to admit fault, and was placed on suspension by the department.

Two Queens-based pros Murray had been training with, Eric Winbush and Mark Weinman, cautioned Murray against fighting as a pro while he was distracted by the charges and a subsequent civil suit when the other officer sued him for $1 million.

“I do regret not doing it,” Murray admitted.

The protracted legal battle turned out to be a blessing in disguise. After going through several attorneys, he was broke and unable to afford legal counsel, and he had to try the case himself in Manhattan Supreme Court. In 2001, eight years after the incident that had him tied up in courts, Murray wound up beating the suit. “The judge told me to go to law school,” Murray says, likening the ordeal to the 1992 comedy My Cousin Vinny.

He did just that, retiring from the police force in 2002, and graduating from Queens College the following year. In 2006, Murray graduated from CUNY School of Law and then passed the bar in New York state.

Murray says he’s defended boxers in the past but didn’t want to name any of them. One of his recent cases was representing UFC fighter Michael Chiesa in his lawsuit against Conor McGregor stemming from the incident in April 2018 when McGregor threw a hand truck through a bus window, injuring Chiesa.

At the end of Election Day, the math was too great to overcome. Katz declared victory less than an hour after polls closed, winning 75 percent of the vote to 25 for Murray.

Murray isn’t done fighting yet, however. He’s part of a 40-and-over boxing program in Westbury, Long Island, but says he’s had to lay off the in-ring action while campaigning. The bouts get heated at times, but he says they all meet up afterwards for a bite to eat.

“I told them Saturday after the election, this Saturday, is my first day back,” said Murray.

“I’m so looking forward to it.”

Ryan Songalia is a member of the Boxing Writers Association of America and part of the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism Class of 2020. He can be reached at [email protected].