Boxing’s Satellite Promotional Tour

It’s shortly before noon on Thursday, May 2, 2019. In two days, Saul “Canelo” Alvarez and Danny Jacobs will do battle at the T-Mobile Arena in Las Vegas for the middleweight championship of the world. Over the next two hours, the fighters will engage in a ritual that has become an integral part of promoting big fights – the satellite tour.

Dave Coskey, who has enjoyed a long career in media and public relations, was one of the early architects of the boxing promotional satellite tour. He was working for the Philadelphia 76ers when Julius Erving retired at the end of the 1986-87 season. There was a pre-game retirement ceremony, and Coskey arranged to distribute it via satellite to stations that wanted to televise the festivities.

Later, Coskey became Senior Vice President for Marketing at the Trump Plaza in Atlantic City. On February 3, 1990, Vinnie Pazienza fought Hector Camacho at the Atlantic City Convention Center. That week, for the first time, Coskey used a satellite tour to promote boxing.

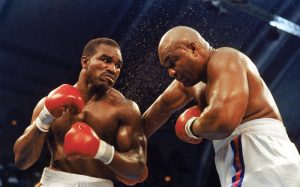

Fast-forward to April 19, 1991, when Evander Holyfield and George Foreman squared off at the Convention Center with the Trump Plaza as host hotel for the fight.

“The goal,” Coskey remembers, “was to make Holyfield-Foreman bigger than a sporting event. And George was a publicist’s dream. Six days before the fight, he preached in a tiny church in Atlantic City, and we set up a satellite feed for ESPN.”

Mark Taffet (who served as senior vice president of sports operations and PPV for HBO) picks up the narrative.

“Bob Arum was the CEO at Top Rank, which was promoting Foreman,” Taffet recalls. “Dan Duva was in charge at Main Events, which promoted Evander. They came to us with Dave Coskey, gave us the creative idea, and we implemented it. Basically, it was get a camera, chair, and some lighting; have each fighter sit in the chair in front of the camera for an hour answering questions from a series of TV stations; and transmit it by satellite. Some of the interviews aired live. Some were taped and aired later. It was easy to do and a way to accommodate the fighters’ fight-week schedules.”

“Bob Arum was the CEO at Top Rank, which was promoting Foreman,” Taffet recalls. “Dan Duva was in charge at Main Events, which promoted Evander. They came to us with Dave Coskey, gave us the creative idea, and we implemented it. Basically, it was get a camera, chair, and some lighting; have each fighter sit in the chair in front of the camera for an hour answering questions from a series of TV stations; and transmit it by satellite. Some of the interviews aired live. Some were taped and aired later. It was easy to do and a way to accommodate the fighters’ fight-week schedules.”

“We realized very quickly that this was a great marketing tool for pay-per-view,” Taffet continues. “It was a win-win situation for the TV stations and the promotion. It cost next to nothing to produce. We were able to target the audience we wanted. There was very little preparation and production involved. Back then, you needed a satellite truck onsite and had to buy an hour of satellite time. Now you can do it all through the internet.”

Satellite tours aren’t unique to boxing. They’re used to promote all kinds of commercial ventures. For example, a pharmaceutical company that’s launching a new product might make a spokesperson available to media outlets for interviews.

The staging ground for satellite tours in conjunction with big fights varies. Sometimes interviews are conducted in the arena where the fight will be contested. That provides a nice camera backdrop. But often, the arena is unavailable or background noise caused by workers setting up seats or erecting scaffolding will interfere with audio transmission, and a quiet room is chosen.

For maximum impact, satellite tours are conducted as close to fight night as possible. But that can conflict with the desire of the fighters to shed media obligations and focus completely on the more difficult task of fighting. Thus, more often than not, the interviews take place on Thursday, two days before the fight. Generally, a fighter’s camp gives satellite tour organizers one hour to work with.

Kelly Swanson is CEO of Swanson Communications, a public relations and marketing firm that offers satellite tours as a turnkey service.

“Obviously, you want the big national outlets like CNN and ESPN if you can get them,” Swanson says. “But some regulars reach out to us for a spot and we try to accommodate them. And you look for markets that might have a special connection to one of the fighters. If Keith Thurman is fighting Manny Pacquiao, you reach out to local TV in Tampa [Thurman’s hometown].”

Mike Tyson was the most sought after fighter on satellite tours. His dance card was always full. The problem was, Tyson sometimes blew off his satellite tour obligations. And even when he showed up, there could be problems.

On January 16, 1999, Tyson fought Frans Botha after a nineteen-month layoff occasioned in part by a suspension imposed after he bit off part of Evander Holyfield’s ear. During the satellite tour, Tyson was interviewed by Russ Salzberg of 9 News. The interview – reproduced here in its entirety – did not go well.

Salzberg: Mike, Francois Botha, a 6-to-1 underdog. Are there any concerns on your part?

Tyson: I don’t know anything about that. I don’t know nothing about numbers. I just know what I can do. How about killing this m—–f—–.

Salzberg: Okay. How about the nineteen months off?

Tyson: What about it?

Salzberg: Does it pose any problem to you?

Tyson: We’ll see. I doubt it seriously.

Salzberg: You take into the ring a lot of rage. Does that work for you or does it work against you at times?

Tyson: Who cares. We’re in a fight anyway. What does it matter?

Salzberg: Well, for example, rage against Evander Holyfield worked against you.

Tyson: Well, f— it. It’s a fight. So whatever happens happens.

Salzberg: Mike, why do you have to talk like that?

Tyson: I’m talking to you the way I want to talk to you. If you have a problem, turn off your station.

Salzberg: You know what. I think we’ll end the discussion right now.

Tyson: Then we could. F— you.

Salzberg: You got it. Have a nice fight, Mike.

MT: F— off.

Salzberg: Class act, buddy.

The satellite tour for Canelo-Jacobs was overseen by Ed Keenan. The first tour that Keenan worked on was for Lennox Lewis vs Mike Tyson in Memphis in 2002. The interviews were scheduled to be conducted immediately after the weigh-in. Then Tyson refused to participate, telling those in charge to perform unnatural acts upon themselves and leaving Lewis to carry the ball. Keenan now owns Event Marketing & Communications. And he’s still coordinating satellite tours.

Room 309 in the MGM Grand Conference Center has a high ceiling and is large enough to accommodate a cocktail party for a hundred people. Seventy metal-framed cushioned chairs were scattered about. One chair was set in front of a black backdrop that bore logos for Canelo-Jacobs, DAZN (which would stream the fight), Golden Boy (Canelo’s promoter), Matchroom Boxing (Jacobs’s promoter), Tecate (the fight’s lead sponsor), Hennessy (which has an endorsement contract with Canelo), and the MGM Grand (the site hotel). There was one cameraman who would shoot one camera angle showing each fighter from the chest up.

Room 309 in the MGM Grand Conference Center has a high ceiling and is large enough to accommodate a cocktail party for a hundred people. Seventy metal-framed cushioned chairs were scattered about. One chair was set in front of a black backdrop that bore logos for Canelo-Jacobs, DAZN (which would stream the fight), Golden Boy (Canelo’s promoter), Matchroom Boxing (Jacobs’s promoter), Tecate (the fight’s lead sponsor), Hennessy (which has an endorsement contract with Canelo), and the MGM Grand (the site hotel). There was one cameraman who would shoot one camera angle showing each fighter from the chest up.

Keenan sat at a small table, smart phone in hand with a laptop in front of him, coordinating it all.

Canelo arrived five minutes after noon, wearing a red track suit with white trim. Trainer Eddy Reynoso, manager Chepo Reynoso, and publicist Ramiro Gonzalez were with him.

The Hispanic-language media has played a huge role in Canelo’s commercial success in the United States. It’s a market that DAZN needs to tap into if it’s going to succeed in building a profitable subscription base. Half of the day’s satellite interviews with Canelo would be with Spanish-speaking networks.

News is seldom made during a satellite tour interview. They’re generally bland with questions and answers that tend toward the repetitive. Canelo sat through eight interviews, taking questions in English and Spanish but answering in Spanish. When called for, Roberto Diaz (whose duties with Golden Boy transcend his official role as matchmaker) translated the answers into English.

Canelo sat patiently through it all, hands folded in his lap, occasionally gesturing with his right hand to make a point. From time to time, he stretched out his legs, crossing them at the ankles.

How did he feel about the constant talk from Danny Jacobs’s camp regarding whether or not Jacobs could get a fair shake from the judges in Las Vegas?

“It sounds like they’re making excuses for losing already.”

What was the highlight of Canelo’s career to date?

“I’ve done a lot of good things in my career, and I’m confident that there are more to come.”

How would he define himself?

“I’m a calm person.”

What did he think about Jacobs having had cancer?

“It’s admirable what he has overcome.”

If Canelo wasn’t a boxer, is there another sport he could have excelled at?

“I think I could have been a good Formula One driver.”

After an hour, Canelo’s interviews were done.

Jacobs arrived at 1:25 PM (ten minutes later than scheduled) and took his seat in front of the camera. His rich baritone voice contrasted markedly with Canelo’s softer tones. There were seven interviews.

What would be the key to the fight?

“It’s about me being the best version of myself that I can be . . . I’m not going to put pressure on myself to overperfom and do things I’m not used to doing . . . Canelo is a great fighter, but he has weaknesses and it’s up to me to exploit those weaknesses.”

Most of the interviewers asked at least one question about Jacobs’s battle against cancer.

“Boxing taught me to view each and every obstacle as just another opponent. Cancer was just another opponent, and I had my hand raised at the end.”

What worried him most about Canelo?

“Nothing worries me about Canelo. If there’s hardship for me in the fight, I’ll overcome it.”

At one point, there was an audio problem at one of the TV stations. The volume wasn’t coming through loudly enough.

“I can’t help you with that,” Jacobs said. “I’m not a tech guy. I’m just a boxer.”

An interviewer asked a question about The Iron Throne.

“I’m sorry,” Jacobs answered. “I don’t know what that means.”

The question was explained.

“I’m sorry, “Danny said again. “I don’t watch much television. I’ve never seen Game of Thrones.”

After 45 minutes, his job was done.

Today’s technology – social media, streaming video, more websites than most people can fathom – offers far more alternatives to promoting a big fight than were available when George Foreman fought Evander Holyfield in Atlantic City a quarter-century ago. But in many respects, the satellite tour is still the most cost-efficient, effective pay-per-view marketing tool available.

Thomas Hauser’s email address is [email protected]. His next book – A Dangerous Journey: Another Year Inside Boxing – will be published this autumn by the University of Arkansas Press. In 2004, the Boxing Writers Association of America honored Hauser with the Nat Fleischer Award for career excellence in boxing journalism.