For heavyweight underdog Bert Cooper, ‘almost’ was pretty damn memorable

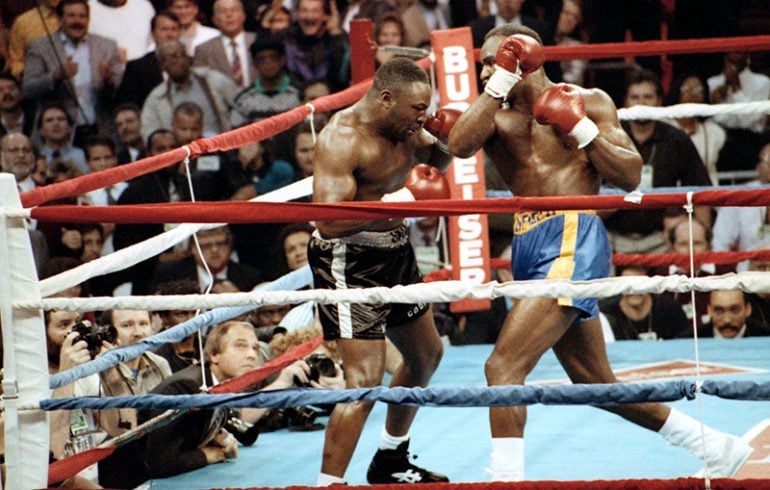

One punch away. That’s how close Bert Cooper was to becoming the heavyweight champion of the world on November 23, 1991, the night he fought Evander Holyfield in Atlanta.

Cooper had won four straight against lesser competition, but had gotten the title fight thanks mostly to everyone else deemed more worthy being sidelined with an injury. First it was Mike Tyson who pulled out with a rib injury, then Francesco Damiani with an ankle injury. Cooper was the replacement of the replacement, and was listed as a 22-1 underdog by the Mirage sports book, the only Vegas betting parlor that saw it worthwhile to list odds for the fight.

For two rounds it looked everything like the stay-busy fight until a minute into the third, when an overhand right to the temple turned Holyfield’s legs to rubber bands. A series of overhand rights and lefts followed along the ropes, and referee Mills Lane gave the barely conscious Holyfield a brief reprieve with a standing eight count.

“He saved Evander Holyfield,” George Foreman said of Lane’s count, noting that Cooper didn’t get a similar count when he was ready to go later in the fight. Of course, Holyfield came right back that same round, and stopped him in round 7, but that’s what made Holyfield Holyfield.

“I didn’t complain because I was too tired,” said Cooper, who earned $750,000 to Holyfield’s $6 million that night. “Who wants to argue? Just pay me.”

Cooper died Friday of pancreatic cancer at the age of 53. The news was confirmed to The Ring by Cooper’s former manager Vinny LaManna, and a Facebook page claiming to be his official account said he had been diagnosed just a month ago.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NZtkqt2_FKg

It’s easy to look at Cooper’s record – 38-25 (31 knockouts) – and dismiss him as a journeyman, but those numbers are just as good thrown out the window. On any given night, you didn’t know which Cooper you’d get. You could get the Cooper that spun Holyfield backwards and left him drooped along the ropes, the one who welcomed Michael Moorer to the heavyweight division with two knockdowns before being overpowered in the fifth, or you could get the version who had his purse held up after quitting before the third round against George Foreman.

He had gotten close at times to winning the big one. He was frustrating to root for, but more times than not, Cooper was worth tuning in for.

For Cooper, it all started back in the Philadelphia suburb of Sharon Hill, Pa. The ninth of eleven children, he was 12 when a woman identified in a 1996 profile piece in the Herald News as Mrs. Turner suggested he’d make a fine boxer. That following Sunday his father took him to Joe Frazier’s gym. Frazier became a second father to him, allowing him to use his “Smokin’” monicker (his personal pet name for Cooper was ‘Scam Booger’) and even billing him as Cooper-Frazier, an adopted son, in some early reports. Cooper was short and stocky at 5’11”, fighting out of a log cabin defense and cranking uppercuts and hooks, not unlike his mentor.

Turning pro in 1984 as a cruiserweight, Cooper ran his record to 16-2 with Frazier, handing 1984 Olympic gold medalist Henry Tillman his first defeat and leveling an unbeaten Willie de Wit in two rounds. Cooper was closing in on a $1 million purse against Mike Tyson in December of 1987 if he could get past a Carl Williams who hadn’t fought in 16 months since being stopped in two by Mike Weaver. No dice, Cooper came in listless and was stopped on his stool.

That was as far as Cooper and Frazier went together. Cooper’s contract was up, and bad blood developed as Cooper’s drug problem – which he’d been able to hide – became more conspicuous. Cooper blamed his fall from grace on Frazier, saying it was his idea to move to heavyweight to follow in his steps, and that he felt his best division was cruiserweight. Frazier’s son Marvis said that was seen as a public betrayal, and Frazier never forgave him.

“When I was a kid, he used to open his coat and say ‘Here, kid, take your best shot,’” Cooper said in a 1991 article. “I’d like to take that shot now.”

Those drug issues became public when, after the Foreman debacle, he tested positive for cocaine. He did a two month stretch in rehab, but sobriety is a process, not a destination. He was arrested in 1992 – a week after the Moorer thriller – on cocaine possession and drug paraphernalia charges after a a bag with a “powdery residue” and a “cocaine pipe” were found in his possession.

Aside from the Holyfield and Moorer fights, there was also the Ray Mercer brawl of 1990 that holds up as a rewatchable classic. He also could be counted on a fun blowout of an overmatched prospect with an inflated record, like when an uppercut broke Cecil Coffee’s nose in round two and left him leaking like a faucet, or when his left hook sent Tony Fulilangi spiraling to the canvas in 4, or the infamous 1997 outing when he gave the jacked up Richie Melito a reality check on USA, spiking him to the canvas in one round.

Cooper and 1988 Olympic gold medalist Ray Merecer went at it for 12 thrilling rounds. Photo from The Ring archives

The Moorer loss effectively ended his run as a heavyweight threat. He’d fight on and off for the next 20 years, losing more than he’d win, and took an eight-year break in 2002 before coming back for five more fights, losing his last three before hanging up the gloves for good in 2012 at the age of 46.

Even at the end, he had heavy hands. Ask Chauncy Welliver, who faced Cooper in his penultimate fight. “I got careless in the ninth round and he hit me with a right hand that had my head ringing and was the first time I’d ever been shook,” said Welliver, who was used to big punchers, having previously sparred David Tua.

“Bert was nice before and after the bout. It’s rare you ask your opponent for an autograph, but I did.”

Cooper was all fighter, but away from the ring there was also a person.

“He was a great guy and fun to be around, loved his wife Dolphine,” said LaManna, who managed him for two years during the mid-90s. “He drove me crazy with the song by Joe ‘All the Things (Your Man Won’t Do)’, and he also took me for my first ever Philly cheese steak in Philadelphia.”

There’s a phrase I’m fond of reciting, usually with a heavy dose of snark: “Watch boxing, not BoxRec.” For no fighter could that be more appropriate for than Bert Cooper.

Ryan Songalia is a member of the Boxing Writers Association of America and part of the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism Class of 2020. He can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter at @ryansongalia.