Errol Spence Jr.-Mikey Garcia: Daring to be great

Editor’s note: This feature appeared in the April 2019 issue of Ring Magazine

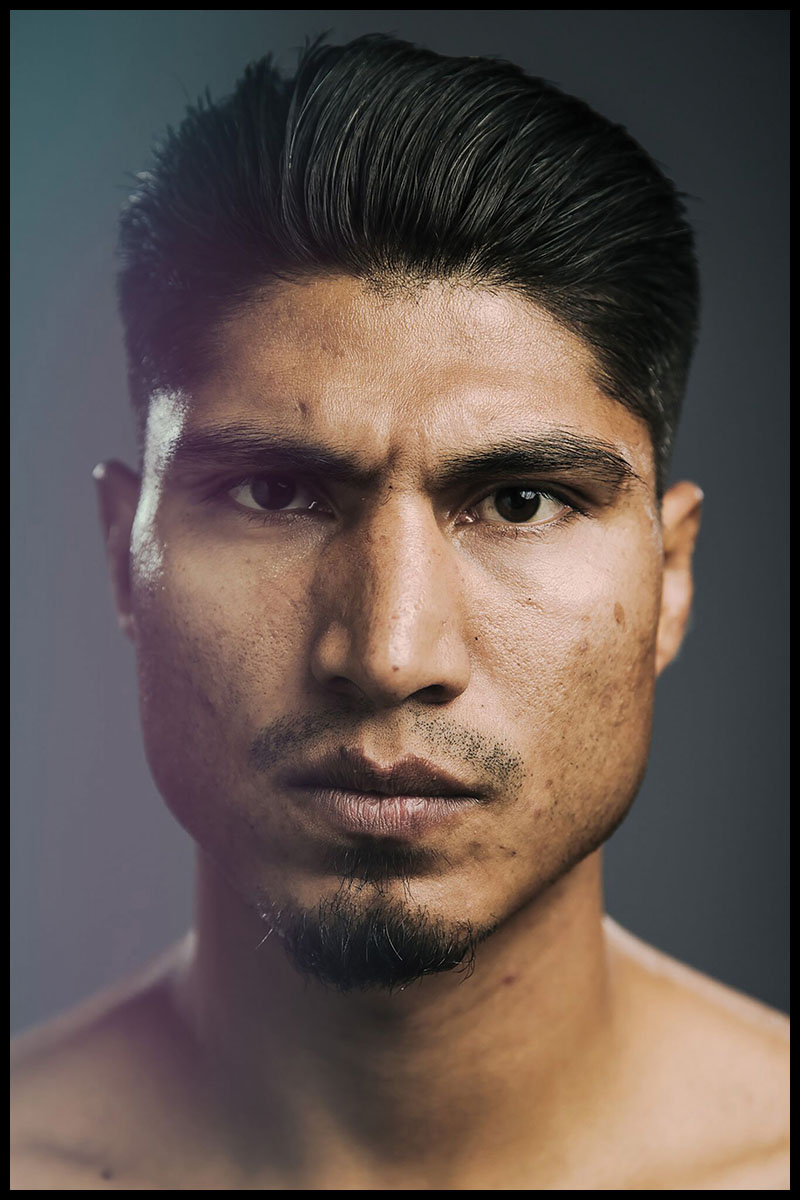

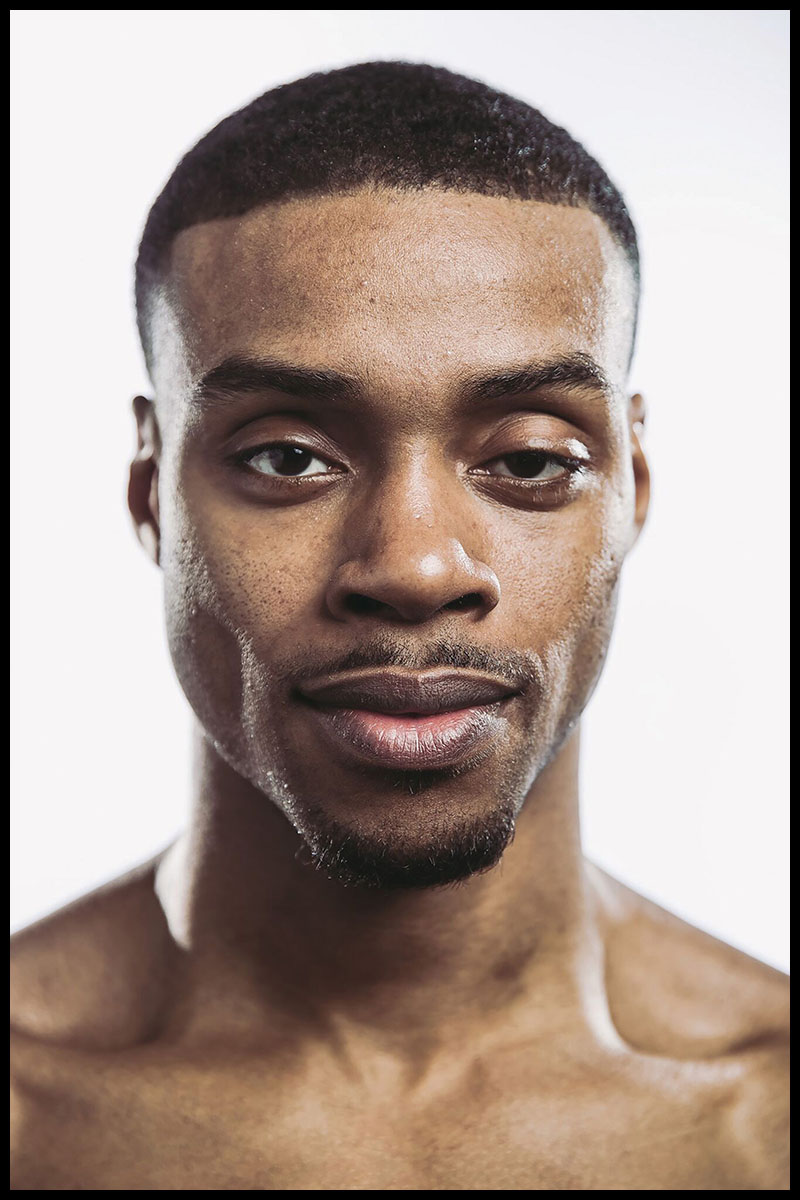

IN AGREEING TO FACE EACH OTHER, MIKEY GARCIA AND ERROL SPENCE JR. HAVE PUT THEIR PERFECT RECORDS, REPUTATIONS AND PRIDE ON THE LINE – AND NEITHER WOULD HAVE IT ANY OTHER WAY

Errol Spence Jr. and Mikey Garcia are pursuing greatness, which is why they are pursuing each other. It is a pursuit fraught with danger, a risk both accept knowing it is the cost of becoming something more than just another fighter wearing a title belt.

In this day and age, there is no end to “champions.” Once, there were eight weight classes and one recognized titleholder in each. It was universally known who the champion was, and everyone else pursued him because the road to greatness was clear. It passed through whomever held that belt. Today, it is a far different landscape. Boxing is as fractured as if the San Andreas Fault had finally cracked and sent half of California tumbling into the sea.

There are 17 weight classes today, but that is only the beginning. Depending on how many sanctioning organizations you care to acknowledge, there are between one and six of them handing out belts (The Ring only recognizes the WBC, WBA, IBF and WBO, but there are also the IBO and IBA), which leaves you with between 17 and 102 champions … and that’s if you exclude “interim champions” (aren’t they all?), “regular” champions and “champions in recess.”

It is a staggering number that has rendered the word “champion” often meaningless and always difficult to quantify. It is why some fighters have come to the conclusion that they must define themselves rather than allowing someone’s belt to do it for them, which brings us to Spence and Garcia.

The Ring’s 147-pound championship is currently vacant, but there are at the moment five welterweight “world titleholders.” There is Spence, who holds the IBF title; the oft-MIA Keith Thurman, who is the WBA “super” champion; Shawn Porter, the WBC beltholder, Terence Crawford, who wears the WBO strap, and the IBO’s Thulani Mbenge. (Future Hall of Famer Manny Pacquiao holds the WBA’s secondary or “regular” title, and the IBA title is vacant.) With so many titleholders, it is left to fans, the media and tweeting boxers themselves to declare who the true champion is – and many believe it is Spence, the undefeated (24-0, 21 knockouts) Texan who has speed, power, size and supreme belief in himself and his skills.

Garcia, on the other hand, has already won titles in four weight divisions from featherweight to junior welterweight and chose to relinquish the uppermost in favor of defending his WBC lightweight belt last July. To achieve what he seeks – which is legend status – he must not only defeat arguably the best welterweight in the world on March 16 at AT&T Stadium in Arlington, Texas. He must pack on 12 pounds or so of muscle to do it.

No one else is willing to do what I’m doing. After this fight, everybody will really recognize me as the top fighter.

– Mikey Garcia

Garcia is making the kind of jump greats like Henry Armstrong made, moving up a full weight class without the benefit of facing even one lesser 147-pound challenge before squaring off with The Ring’s No. 1-rated welterweight.

For Spence, the challenge is different, although no less daunting. While Garcia may not yet be a legitimate welterweight, he is a proven elite-level boxer, and like Spence, ranked among the top 10 pound-for-pound in the world. That may not make either a legend, but it establishes that both are dangerous. Extremely so, which only makes Garcia’s choice to step in with Spence more significant.

Neither needed to choose this route. Spence had numerous options, both for unification fights and less dangerous contenders while he marked time for the Big Fight he craves. Garcia faced the same situation, not only in the lightweight and junior welterweight divisions but now at welterweight, where he could have easily justified fighting a less formidable opponent first.

READ: Manny Pacquiao and History’s Greatest Weight-climbers (RingTV article from 2010, as Pacquiao prepared to face Antonio Margarito for the vacant WBC junior middleweight title)

In fact, Garcia’s father and brother, who have trained him since he was a teenager and throughout most of his professional career, cautioned him to do just that. Both tried to dissuade him when he first raised the idea of facing Spence, but like the 39 fighters and one promoter who have challenged Garcia during his career, they lost.

“My father and I were against it at first,” admits Robert Garcia, a former IBF titleholder himself who will now prepare his younger brother for the biggest fight of his career. “We told Mikey there were so many other fights he could take and still make a lot of money.

“We thought he should take his time, and when the time was right, move to 147. We didn’t think it was impossible, but why not wait? But Mikey is different than everyone else. He wouldn’t feel right facing opponents who don’t mean that much. We all know Spence is a difficult fight. He’s very fast. He has great power. He works to the body very well. Obviously Mikey will feel that power at welterweight with eight-ounce gloves. But Mikey talked to both of us, and then my Dad told me, ‘It’s done. Now we train him to win.’

“We have a fighter who is very smart in the ring. On the outside he looks very basic, but when you get in with him you realize how difficult he is. I’ve worked with 12 world champions, but Mikey’s the special one.”

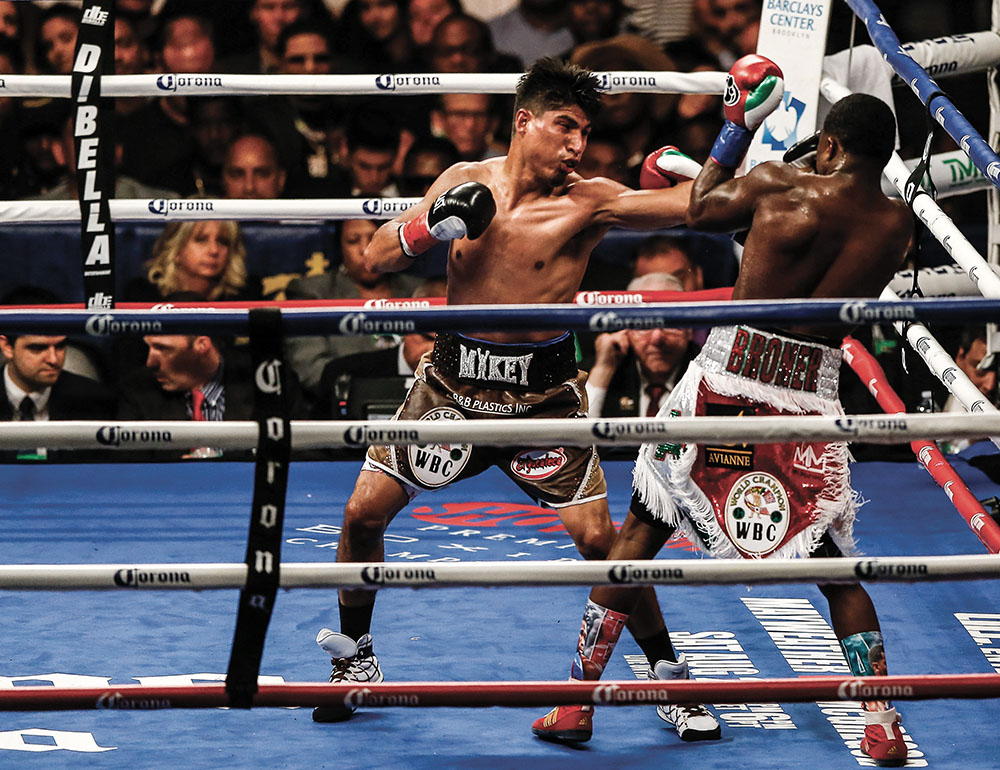

Garcia proved he is more than capable of fighting above lightweight with a one-sided decision over Adrien Broner in July 2017.

He will have to be to beat Spence, who is not only naturally bigger but will have the advantage of fighting in his hometown, where his love of boxing began unexpectedly at the age of 15 after his father took what was then a budding football star for a summer drive. Where they ended up was hotter than the stifling Texas air outside.

“The last place I thought we’d be going was to a boxing gym,” Spence recalled. “It was a real old-school gym. No A/C. Whatever it was outside is what it was inside. The first couple days I was a little bit confused.

“The second week, I sparred a guy three weight classes above me. I was 120-something. He dropped me with a body shot. That was eye-opening! But I came back the next day. I liked it but I didn’t really care for it. At first, I did want to quit, but my father told me if I quit at this I’d quit at anything. He made me stick it out.

“I knew I was good two years into it. I started doing research on fighters. I knew about the Olympics but not boxing in the Olympics. I found out about Sugar Ray Leonard, Ali, Foreman and Roy Jones. I had high hopes for it.”

Those hopes were crushed in the quarterfinals of the 2012 Olympics in London in the way many American amateurs have lost in recent Olympics – by the kind of hotly disputed decision that Spence says “robs you on the greatest stage in the world. I was heartbroken. It was hard, man.”

He turned pro several months later and within five years was facing IBF welterweight titleholder Kell Brook in Sheffield, England – Brook’s hometown. Home cooking did Brook little good, however, as Spence survived a sluggish start after having had “chocolate brownies thrown at me” during his ring walk (a reference to a pre-fight taunt made by Brook) and overwhelmed the champion. He threw no brownies. Rather, he threw lightning-quick jabs and crisp hooks that forced Brook to take a knee in both the 10th and 11th rounds before the fight was mercifully stopped with the orbital bone in Brook’s left eye shattered along with his spirit.

“I didn’t feel that sharp, but a true champion still wins,” Spence said at the time. And he went on to do so twice more, stopping Lamont Peterson and Carlos Ocampo while consistently calling out Thurman without much of a response.

“I’m waiting for ‘Sometime’ Thurman,” Spence said, poking fun at Thurman’s “One Time” nickname after forcing Peterson, both eyes swollen shut and having already made one trip to the floor, to retire on his stool after the seventh round. “I’ve been waiting a long time.”

That wait continues. But in the interim, Garcia called him out and Spence responded affirmatively, noting for the record his admiration for the step Garcia is taking. It is a step many of Spence’s full-blown welterweight rivals have been less than enthusiastic about.

“I think he did it because he wants to be the best,” Spence said of Garcia. “This is a history fight for him. I give him all the respect in the world. He’s daring to be great. You don’t get that a lot in this day and age.

“He’s very smart. He’s a good, technical fighter with a lot of skills. He’s the first guy to call me out. He’s the biggest name I can get right now. I know he’s serious about it. He comes to win and so do I.

“He wants to move up and dethrone me. He knows this is a legacy fight for him, but it’s a win/win for him. If he loses, they’ll say I was too big for him. If he can dethrone me, he’ll be pound-for-pound number one. I respect what he’s trying to do, but that’s not going to happen. I’m the stronger fighter. I’m the better fighter.”

While Garcia shares the same respect for Spence and a similar late start in the sport, he has spent his life around boxing and understands the significance of this moment. He has pursued it for nearly 20 years after unexpectedly finding himself inside a boxing ring at the age of 13, untrained but right at home.

“A kid didn’t have an opponent and they asked me to fight,” recalled Garcia, who is the youngest of seven siblings, born into a fighting family but without a bit of interest in it when this all began. “I’d never trained, but I knew a little bit. I wasn’t even a licensed amateur. It just came natural to me. I became aware that day I could do it very easily. It was fun.

“I never thought I’d be a boxer. I never wanted to. For me, that was my brothers fighting. That was my father’s business. That was (Fernando) Vargas at La Colonia (the Oxnard, California, gym where Eduardo Garcia developed Vargas and Robert into world champions and hundreds of other kids into more disciplined young men). I would just go watch. I never played other sports either. I was into video games.”

Regardless of his preferences, Mikey Garcia was a child prodigy, a master of a dark art who realized almost immediately he’d been touched. Like Spence, he has a gift and decided to use it.

“It was boring at times because it was so easy,” Garcia said of his early days in boxing. “I was like a kid playing video games. Once you reach the hardest level and you beat that game a few times, you stop playing it and look for something challenging.”

His official amateur career began at 14, and by 19 he’d turned pro, running up a 30-0 record with 26 KOs before facing veteran Orlando Salido for the WBO featherweight title on January 19, 2013. Although Salido had nearly twice as many professional fights, the prodigy overwhelmed him. Garcia knocked him down four times, including twice in the first round, before winning a technical decision after Salido’s head broke Garcia’s nose in the eighth round and the doctor stopped the bout. They didn’t have to read the cards to know who won.

Garcia has gone on to win the WBO junior lightweight, the WBC lightweight and the IBF junior welterweight titles while improving his record to 39-0. Actually it should be 40-0, because he also forced a settlement with promoter Bob Arum after a contract dispute, though it drove Garcia into a 2½-year layoff in the prime of his career.

That fight, like the one he’s made with Spence, was opposed by his family and friends. Looking back, Garcia admits had he known he would be out of the ring so long, he might have tried another road. But, as with his decision to jump from 135 to 147, he has no regrets.

“I bet on myself,” Garcia said. “There were times it was difficult and scary. There was no finish line in sight, but I kept believing it would happen, and it’s paying off with interest now. If anyone thought that was going to hurt me, they were wrong. My fan base actually grew during my layoff. That kept reassuring me.

“Some fighters need a promoter even after they’re champion. Not every fighter is able to do it on their own. To develop a fighter, you need a good promoter. Top Rank (Arum’s company) did a great job with me. They know how to build a fighter, but I was at a stage I felt I should have been bigger than I was. Now I’m a free agent. I control my career. I don’t have any short-term deals or long-term deals (with promoters or cable networks). I’m willing to work with any promoter.

“Now I can get the fights I want. I can do what’s best for my career – not someone else’s agenda. I bet on myself because I believe in myself so much.”

That belief has led Mikey Garcia to this moment. To stepping up the way old-school guys like Homicide Hank once did, although no one will ever again hold world titles in three separate weight classes simultaneously, as Armstrong managed to do in 1938 when he added the lightweight and welterweight championships to the featherweight title he won the previous year.

It is feats like that which define greatness in boxing, and Garcia and Spence both know it. While these are different times, Garcia’s decision to give up four inches in reach, nearly as much in height and most certainly an edge in punching power is his version of seeking what only the greatest fighters achieve.

If he loses, they’ll say I was too big for him. If he can dethrone me, he’ll be pound-for-pound number one. I respect what he’s trying to do, but that’s not going to happen. I’m the stronger fighter. I’m the better fighter.

– Errol Spence Jr.

Many have titles. Only the few leave a legacy behind them, and that comes only if you’re willing to risk it all for glory.

“At this point in my career, I’m looking for greatness,” Garcia said. “If it means you move up a weight division, more power to me. If it means you go to someone’s hometown, more power to me. It’s the same fighter in front of me whether we fight in Dallas or New York or Vegas. In the end, it’s another four ropes and four corners.

“Spence is very good. He reminds me a little of myself. He’s not the flashiest guy, but he does have good power. I think that’s a reflection of his opponents a little bit, but you have to have power to hurt a guy. It’s apparent he has that.

“So why fight him? I do need this fight. I need a marquee name and I just feel I’m a better fighter. I’m only getting better, faster. I adjust very well. I’ve never had a problem with southpaws. If I have to fight him on the outside and make him reach, I will. If I have to stay on the inside to take away his reach and work his body, that’s what I’m prepared to do.

“No one else is willing to do what I’m doing. After this fight, everybody will really recognize me as the top fighter. My dad and brother wanted me to take someone else, but anyone else coming off a loss or a has-been doesn’t do it for me. I see the reasoning behind what they were saying. I’m a small guy to begin with who never fought at 147. It’s logical to fight someone who isn’t as threatening first to get a feel for it. I considered it, but I’m always looking for the biggest challenges. No one else motivated me other than Errol Spence. I want to beat great champions.

“Most people don’t see what the fighter sees inside the ring. They don’t have the eye for it. Even most fighters don’t. They look at me and don’t see anything special. They’re right. I don’t have any special skills that set me apart. You don’t see anything too out there. I’m pretty basic.

“It’s the subtle little moves that make the difference inside the ring. I’m always one step ahead. Opponents don’t see that on video. When they get in the ring, they realize it’s a whole different experience. I don’t have any doubts. I know I’ll win.”

Spence feels the same way. But only one can win, and the boxing world isn’t quite sure who it will be. Many think Spence’s size will prove too much to overcome, but others point out that when challenged, Garcia has never been found wanting.

Robert Garcia knows the pitfalls and dangers that come with facing Errol Spence. The trainer does not hide from the difficulties they will face on March 16. But he also knows his brother.

“You cannot take anything away from Errol Spence,” Robert Garcia said. “He is a complete fighter. He’s very talented. But I guarantee you two things: Errol won’t be stronger than Mikey and he’s never been in with a guy like Mikey. Spence has to know he’s in for a fight. And so are we.”

Whoever has his hand raised that night will have taken a step toward the greatness both are seeking, a greatness that comes not from the pursuit of title belts but from accepting great challenges. Errol Spence and Mikey Garcia have agreed to do that. What happens next is up to them.

Struggling to locate a copy of The Ring Magazine? Try here or

Subscribe

You can order the current issue, which is on newsstands, or back issues from our subscribe page.