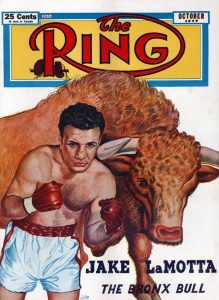

Jake LaMotta, all-time great middleweight and subject of Raging Bull, dies at 95

Jake LaMotta, one of boxing history’s most compelling figures and all-time great fighters, died Tuesday in Aventura, Florida, at age 95, his longtime fiancée, Denise Baker, confirmed.

The Hall of Famer had been in hospice care at Palm Garden Nursing Home in recent weeks and succumbed following a battle with dysphagia pneumonia.

LaMotta is universally regarded as among the toughest and most durable men ever to enter the squared circle. His honors include induction into THE RING’s Hall of Fame in 1985, the World Boxing Hall of Fame in 1986 and charter membership into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990.

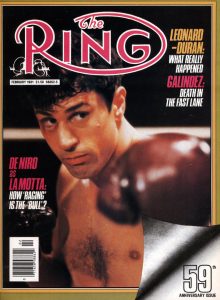

His turbulent life in and out of the ring inspired a 1970 autobiography, a 1986 sequel and, most famously, the classic 1980 film “Raging Bull,” which earned eight Academy Award nominations (including Best Picture), a Best Actor Oscar for Robert DeNiro, who portrayed LaMotta, critical acclaim for director Martin Scorsese and a reintroduction to the public for LaMotta himself.

“The Bronx Bull” was born Giacobbe LaMotta on July 10, 1921 on the Lower East Side of New York City but is most closely associated with the Bronx. His childhood was a violent one, both at home and on the streets. He endured countless beatings from his father, who also abused his mother and siblings and who forced an 8-year-old Jake to engage in fights with neighborhood kids while the adults threw coins and dollar bills that helped pay the rent.

“The Bronx Bull” was born Giacobbe LaMotta on July 10, 1921 on the Lower East Side of New York City but is most closely associated with the Bronx. His childhood was a violent one, both at home and on the streets. He endured countless beatings from his father, who also abused his mother and siblings and who forced an 8-year-old Jake to engage in fights with neighborhood kids while the adults threw coins and dollar bills that helped pay the rent.

This chaotic existence caused LaMotta to erect an impenetrable wall of distrust and to follow a simple code of survival — “hit ’em first and hit ’em hard.”

To escape the horrors of home he ran the streets and committed a series of crimes that eventually led to him being sent to the New York State Correctional School in West Coxsackie, New York, which counts another future middleweight champion, boyhood friend Rocky Graziano, as an alum. LaMotta learned to box there and after being released, he embarked on a brief amateur career that saw him win a Diamond Belt championship. Four months before turning 20, he turned pro.

Despite his lack of one-punch power, LaMotta prospered with hustle, persistent body work and an underrated jab while on defense he blunted attacks by smothering his opponents, rolling his upper body and positioning his arms in a tight package. If all else failed, there was that magnificent chin. That, and a profound self-loathing, fueled a maniacal thirst for dishing out — and absorbing — punishment.

“I wanted to get punished and I took unnecessary punishment when I was fighting,” LaMotta told author Peter Heller in February 1970. “I didn’t realize it but subconsciously I was trying to punish myself. Subconsciously — I didn’t know it then, I realize it today when I know a little bit more about the mind and the brain — I fought like I didn’t deserve to live.”

LaMotta compiled a record of 83-19-4 (30 knockouts) during a 13-year career that ended in 1954. In that time he faced a who’s who of champions and contenders, many of whom he fought more than once. They include Jimmy Edgar (W 10, W 10), Jose Basora (D 10, L 10, W 10, KO 9), Fritzie Zivic (W 10, L 15, W 10, W 10), Lloyd Marshall (L 10), George Costner (KO 6), Tommy Bell (W 10, W 10), Holman Williams (W 10), Bob Satterfield (KO 7), Tony Janiro (W 10), Tommy Yarosz (W 10), Joey DeJohn (KO 8), Robert Villemain (W 12, L 12), Tiberio Mitri (W 15), Bob Murphy (KO by 7, W 10) and Gene Hairston (D 10, W 10).

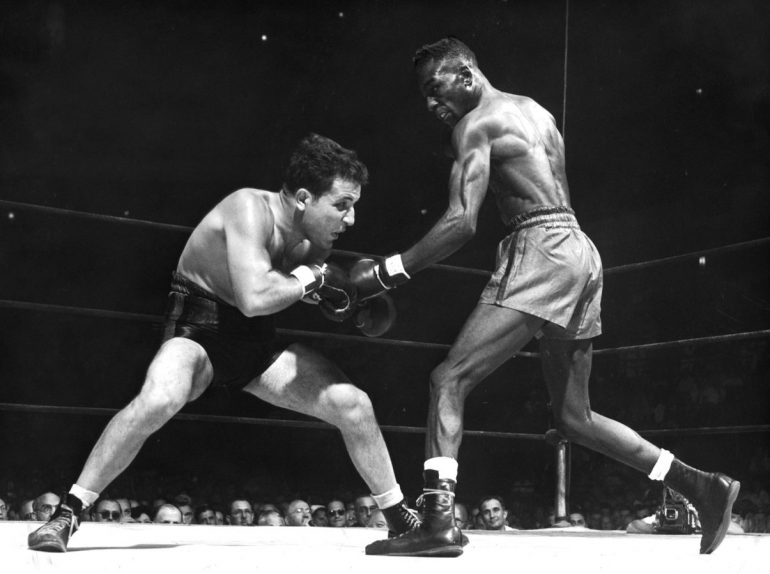

LaMotta (right) throws a left against Marcel Cerdan. Photo by THE RING

In terms of his fistic legacy, however, LaMotta is best remembered for facing four more opponents inside the ring — Marcel Cerdan, from whom he won the middleweight title; Laurent Dauthuille, whom LaMotta stopped in dramatic fashion to retain his championship; the incomparable Sugar Ray Robinson, with whom he engaged in an immortal six-fight series; and Billy Fox, to whom LaMotta voluntarily lost in order to secure the eventual title shot against Cerdan — in addition to one powerful force beyond the ropes: The mob.

The “wise guys” were unavoidably intertwined with LaMotta’s November 1947 fight with Fox. LaMotta, long considered the uncrowned middleweight champion, was denied a chance at the belt because of his unwavering desire to make it to the top without help from anyone, especially the Mafia, which controlled the sport. But after years of being shut out, the 26-year-old LaMotta eventually accepted the inevitable and worked out an agreement: Lose purposefully to Fox, then, at a later date, pay $20,000 and sign a three-year exclusive services contract with the International Boxing Club in exchange for a future middleweight championship fight. LaMotta confirmed the arrangement while testifying before a U.S. Senate subcommittee in July 1960.

Nicknamed “Blackjack,” the 24-year-old Philadelphian backed by gangster Frank “Blinky” Palermo entered the LaMotta bout with an extraordinary 47-1 (47) record, with the only defeat coming in a title fight against world light heavyweight champion Gus Lesnevich eight-and-a-half months earlier. Since that defeat Fox had run off seven straight KOs and on the morning of the fight he was listed as a slim 6-to-5 favorite. The whiff of impending corruption was strong, however, and as a result the odds suddenly surged to 3-to-1 a few hours before the opening bell. This prompted New York State Athletic Commission chairman Eddie Egan to twice visit each man’s dressing room to deliver stern warnings against any shenanigans. But it was too late; the fix was in.

While LaMotta agreed to lose, his pride wouldn’t permit him to hit the canvas. The resulting spectacle inside Madison Square Garden bordered on farce.

“Exposing himself almost as flagrantly as Lady Godiva, Jake refused to go down but threshed and floundered on the ropes, apparently helpless against Fox’s blows, until the referee stopped them in the fourth round,” Red Smith wrote in 1980.

Fox’s lack of talent also was obvious to LaMotta, who nearly scored a disastrous knockout victory in the bout’s opening moments.

LaMotta (right) knocking out Laurent Dauthuille. Photo by THE RING

“Fox can’t even look good,” LaMotta wrote. “The first round, a couple of belts to his head, and I see a glassy look coming over his eyes. Jesus Christ, a couple of jabs and he’s going to fall down? I began to panic a little. I was supposed to be throwing a fight to this guy, and it looked like I was going to end up holding him on his feet. … By (Round 4), if there was anybody in the Garden who didn’t know what was happening, he must have been dead drunk.”

Both fighters’ purses were withheld and two investigations were conducted. On February 13, 1948 Eagan suspended LaMotta for three months and issued a $1,000 fine. The fiasco’s stench was such that LaMotta didn’t get his promised title shot until June 1949.

Nine months earlier, Cerdan seized the championship by pounding Tony Zale into submission, then retirement. The French-based Algerian’s record was an incredible 111-3 (65 KOs) and going into the LaMotta fight he had won 43 of his last 44, 31 by knockout and 25 in four rounds or less. Still, Cerdan was a narrow 2-to-1 favorite.

A fired-up LaMotta pounded Cerdan’s body with both hands in Round 1 and stunned him moments later with a right to the jaw. In the round’s waning moments LaMotta, trying to free himself from a clinch, flung the champion to the canvas, causing Cerdan to land heavily on his left shoulder. From that point on, Cerdan was, according to columnist Red Smith, “a fighting cripple.”

Dr. Vincent Nardiello diagnosed the injury as a torn supraspinatus, the muscle that lifts the arm, but left open the possibility of a ligament tear. The bottom line was that Cerdan’s left arm would be useless for the remainder of the fight. Still, Cerdan soldiered on and at points he more than held his own as he repeatedly pelted LaMotta with overhand rights. But no one-armed fighter could hold off a two-fisted bull for long, especially one with LaMotta’s determination and drive. In the sixth the American, fighting with an injured knuckle on his left hand, ripped rights and lefts to Cerdan’s ribs while rounds seven, eight and nine saw LaMotta pile up big points with ceaseless up-and-down combinations.

Cerdan’s corner stopped the fight between rounds nine and 10 to end LaMotta’s long championship quest. By betting on himself, LaMotta’s $6,000 windfall in addition to his $19,171.50 purse allowed him to make up the $20,000 he paid to get the title shot.

LaMotta celebrates after winning the fight against Laurent Dauthuille. Photo by THE RING

“The road to the title almost broke my heart,” LaMotta said in an interview posted on Boxing.com. “To get a chance at the championship, I had to make a deal with the fight mob, the crooked managers, just as Rocky had gone along with the same kind of wise guys, just as many other fighters have gone along with a system that makes it almost impossible for a fighter to be both independent and successful.”

After beating Villemain, Dick Wagner, Chuck Hunter and Joe Taylor in non-title fights and out-pointing Mitri in his first defense, LaMotta signed to defend against the speedy Dauthuille, who out-boxed LaMotta over 10 rounds 19 months earlier.

The fight was staged Sept. 13, 1950 at Detroit’s Olympia Stadium, where LaMotta had been 13-1 (6 KOs). Only Robinson was able to beat the Olympia Jinx, but that came at a price to Sugar Ray because three weeks earlier, at the same venue, LaMotta became the first man to defeat Robinson.

“The Tarzan on Buzenval’s” neat boxing and timely punching helped him build a massive lead on the scorecards. Entering the final round Dauthuille led 72-68, 74-66 and 71-69 under the five-point must scoring system, which meant that the Frenchman only needed to stay on his feet until the final bell to become the new champion.

LaMotta began the 15th looking so tired and weak that one wondered if he would make it through the round, much less stage any sort of miracle comeback. His upper body was hunched over with exhaustion and his arms hung limply at his sides as he wearily bounced off the ropes several times. Both men appeared to be going through the motions but while that might have been true of Dauthuille, the ever-resourceful LaMotta was setting up a daring trap.

As Dauthuille moved in to attack the “vulnerable” LaMotta, the New Yorker suddenly sprang into action by cranking a series of quick hooks and turning the challenger toward the ropes. Realizing he had just been fooled, Dauthuille tried to escape to ring center but LaMotta maneuvered his upper body to keep the challenger where he was and his fists to administer heavy damage.

LaMotta’s all-out attack escalated with each passing second and Dauthuille could do nothing to turn the tide. A savage hook left Dauthuille’s body draped over the bottom rope and the badly dazed challenger, knowing the title could still be his if he arose, did his best to regain his feet. He did so, but only a split-second after referee Lou Handler completed his count. It is ironic that LaMotta, a man given to superstition, retained his championship with just 13 seconds remaining in the contest.

“I was very, very, very lucky to win that fight,” LaMotta said.

LaMotta’s incredible rally earned him a notable double — THE RING’s Fight of the Year and its Round of the Year. Only round six of Tony Zale-Rocky Graziano II had previously pulled off that feat and it marked the only time LaMotta would win either award.

Five months after taking out Dauthuille, LaMotta defended the title against Robinson, the reigning welterweight champion.

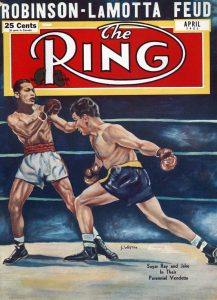

This fight marked the sixth and final act of their legendary rivalry and even though Robinson held a 4-1 lead, every fight was savagely competitive.

Their first meeting at Madison Square Garden in October 1942 saw Robinson overcome a first-round knockdown to win a 10-round decision to run his record to 35-0 but six months later at the Olympia — LaMotta’s home away from home — the bull knocked Robinson through the ropes in Round 8 en route to a 10-round points win that evened the series and inflicted the first loss of Robinson’s pro career following 40 consecutive victories. The pair met just three weeks later, again at the Olympia, and though LaMotta scored a seventh-round knockdown — his third in their three fights — Robinson came away with another decision win.

Their first meeting at Madison Square Garden in October 1942 saw Robinson overcome a first-round knockdown to win a 10-round decision to run his record to 35-0 but six months later at the Olympia — LaMotta’s home away from home — the bull knocked Robinson through the ropes in Round 8 en route to a 10-round points win that evened the series and inflicted the first loss of Robinson’s pro career following 40 consecutive victories. The pair met just three weeks later, again at the Olympia, and though LaMotta scored a seventh-round knockdown — his third in their three fights — Robinson came away with another decision win.

Fight number four took place in February 1945 at Madison Square Garden and the result was the same as Robinson earned another distance win. Their fifth encounter seven months later at Chicago’s Comiskey Park was the roughest of all as Robinson built an early lead only to see LaMotta rally furiously down the stretch. The 12-round split decision for Robinson was hotly disputed, especially by LaMotta.

Now came fight No. 6, the only one that involved a world championship. While Robinson scaled a comfortable 155 1/2 pounds, LaMotta tortured himself before boiling his stocky frame down to the middleweight limit.

“Five days before the fight, practically starving myself, I made 160 pounds,” LaMotta told Heller in 1970. “But I was so weak that I stopped training. I was in Chicago at the time. I just laid around. I had steak three times a day, no vegetables, nothing, just a piece of steak three times a day with a little cup of tea. And when I weighed myself the night before the fight I was 164 1/2.

“I had to lose 4 1/2 pounds. I went to the steam room and that night, all night long, in and out, in and out. Finally, I made 160 pounds that night. I was very weak. I did drink brandy before the fight to give me some strength. And for 10 rounds I beat Robinson. Then I couldn’t lift my hands anymore. I just had no strength left in my hands.”

With LaMotta running on fumes, an eager Robinson hammered LaMotta with his full arsenal of jabs, hooks, crosses and uppercuts, all thrown with full power and landing with frightful flushness. For three straight rounds LaMotta’s rock-hard jaw, sturdy legs and iron will underwent the most severe test any fighter could ever face. The beating was so barbaric that ringside commentator Jack Drees declared during the final minute of round 12 that “no man can endure this pummeling.” But LaMotta did — for another 42 seconds in that round and another 124 seconds in round 13 before referee Frank Sikora finally stopped the slaughter.

“The three toughest fighters I’ve ever been up against were Sugar Ray Robinson, Sugar Ray Robinson and Sugar Ray Robinson,” LaMotta said. “I fought Sugar so many times, it’s a wonder I don’t have diabetes.”

Robinson’s merciless assault, LaMotta’s indomitable bullheadedness and the date of the fight caused the bout to be dubbed “The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre.” Proud to the last, LaMotta said that if the fight had been allowed to continue for another 30 seconds “Robinson would have collapsed from hitting me.”

LaMotta moved up to light heavyweight but he never was able to duplicate the success he enjoyed at 160. In his divisional debut against Bob Murphy he suffered his second consecutive stoppage loss when he retired on the stool between rounds seven and eight, then dropped a 10-round split decision to Norman Hayes and fought Gene Hairston to a draw. True to form, he avenged all three blemishes in his next three fights, all by 10-round decisions.

On New Year’s Eve 1952, LaMotta faced the hard-hitting Danny Nardico, who, midway through round seven, landed a right to the jaw that dropped the New Yorker for the only time in his 106-fight career. Nardico did his best to finish off LaMotta but the former champ managed to survive the rest of the round by leaning against the ropes, rolling under his opponent’s bombs and steadying himself by placing his right glove on the ropes.

Once a survivor, always a survivor.

But even survivors have their limits. After LaMotta walked to the corner and sat on his stool, he decided to remain there. For the fourth and final time he failed to finish a fight. It was clear LaMotta was a spent force and he stayed away from the ring for 16 months before launching a comeback in March 1954. He scored quick knockouts over Johnny Pretzie (KO 4) and Al McCoy (KO 1) in a 24-day span but then he ran into his final brick wall — at least inside the ropes. LaMotta, still only three months from his 33rd birthday, retired for good after losing a split decision to Billy Kilgore 11 days after beating McCoy.

After boxing, LaMotta owned and managed bars, became a stage actor and launched an improbable career as a stand-up comedian. LaMotta’s life soon spiraled downward as he suffered the ravages of alcoholism, divorce and financial ruin. In 1957 he was arrested after a 14-year-old girl, who had been apprehended on a prostitution charge, told authorities that she plied her trade at LaMotta’s Miami Beach club. He was convicted on two counts of promoting prostitution and during his six-month prison term he served on a chain gang.

But the survivor within LaMotta eventually helped him regain his footing. He appeared in 15 films, including a cameo as a bartender in “‘The Hustler,” which starred Jackie Gleason and Paul Newman. He also appeared on several episodes of the TV series “Car 54, Where Are You.” The success of “Raging Bull” — and the forgiving nature of the American public — resuscitated his image and turned the jeers into cheers. Although he continued to marry and divorce — his marriages numbered seven — his life as a whole was far more stable and he appeared to be a much more contented person.

But the survivor within LaMotta eventually helped him regain his footing. He appeared in 15 films, including a cameo as a bartender in “‘The Hustler,” which starred Jackie Gleason and Paul Newman. He also appeared on several episodes of the TV series “Car 54, Where Are You.” The success of “Raging Bull” — and the forgiving nature of the American public — resuscitated his image and turned the jeers into cheers. Although he continued to marry and divorce — his marriages numbered seven — his life as a whole was far more stable and he appeared to be a much more contented person.

Following his induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame, LaMotta made semi-regular appearances at the June festivities and he remained active on the speaking and autograph circuit even into his 90s. Although he faced his share of media criticism during his career, historians have treated LaMotta far more kindly. THE RING ranked LaMotta 52nd on its list of the 80 best fighters of the last 80 years and another article rated him as the fifth greatest middleweight in history.

Historian — and former RING editor — Bert Randolph Sugar ranked LaMotta the 27th greatest pound-for-pound boxer in his book “Boxing’s Greatest Fighters,” saying that “his heart was that of a thoroughbred trapped inside the body of a mule.”

The final paragraph of LaMotta’s second book perfectly described his never-ending quest for happiness, fulfillment and stability. Moments before he accepted the plaque signifying his inclusion into THE RING Hall of Fame he silently rehearsed his opening remarks:

“If it is true that when God examines a man, He looks not for medals, but for scars, then in sixty-odd years of survival in and out of the ring, I feel I have truly earned the title Middleweight Champion of the World,” he wrote. “Thirty-five years ago, I lost that title to a very worthy opponent, Sugar Ray Robinson. Today, you have given it back to me again. This time I have fought not to be a champion gladiator, but to become a champion human being.”

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, W.Va. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 12 writing awards, including nine in the last four years and two first-place awards since 2011. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. He is the author of “Tales From the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics. To order, please visit Amazon.com or e-mail the author at [email protected] to arrange for autographed copies.