Jonathan Taconing’s July 2 title shot goes beyond glory

MANILA, Philippines – The smell of sweat and hard work filled the air of the dusty Elorde Sports Center. The sound of the speed bags were drowned out by the cockfighting taking place upstairs. There were few indications that this was anything other than another mundane Wednesday afternoon in the basement dungeon gym located in the Sucat section of Paranaque City, which is part of Metro Manila.

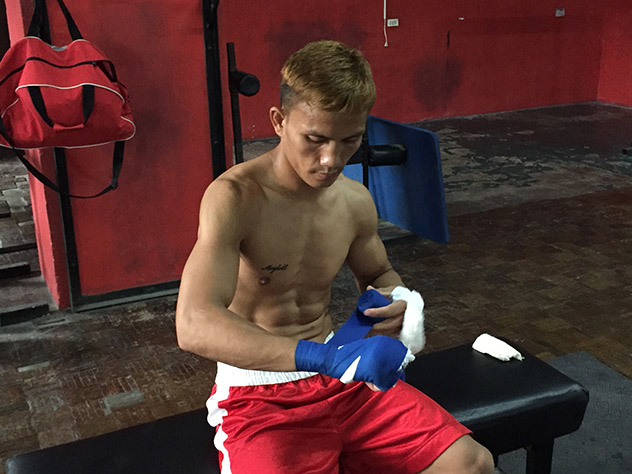

Yet among the scores of young boxers in varying stages of preparation for fights is one who is wrapping up his training camp for the biggest fight of his career. Jonathan Taconing, the WBC’s No. 1 contender at 108 pounds, is preparing for his showdown with junior flyweight titleholder Ganigan Lopez on July 2 at Arena Coliseo in Mexico City, Mexico.

There are no news cameras, no fans waiting outside for autographs the way there would be when Manny Pacquiao is about to leave for a championship fight.

Just him, his trainer Eddie Ballaran and his solitary focus.

“If he gives me the chance, any round, I can knock him out,” Taconing told RingTV.com on June 22, 10 days before the fight. There’s no hint of arrogance when he says this; scoring 18 knockouts in his 22 wins (against two losses and a draw) has been his insurance against outside forces taking away what he had earned in the ring.

At first, [Jonathan] said, ‘I want to quit because nothing is gonna happen for my boxing career’ … I told him, ‘You [will] be a world champion. Not now, but coming soon.’ – Marybeth Taconing

For four years, Taconing has waited for his second shot at a world title, four years after virtually all observers thought he got jobbed out of the same title he’ll fight for this Saturday.

During a steamy afternoon at an outdoor venue in Thailand, an unknown Taconing took the fight to the champion, Kompayak Porpramook (Suriyan Satorn), and appeared on his way to a stoppage victory. The fight did end prematurely, but after an accidental headbutt caused an inconsequential nick in Round 5. One judge saw it as a draw while the other two scored the fight for Porpramook. The World Boxing Council reviewed the performance of Korean referee Jae-Bong Kin and suspended him for a year.

“I feel like I won that fight but it was a hometown decision. That’s just how it goes,” Taconing, known to his friends as “Tata,” says of the fight. His common-law wife, Marybeth, tells a deeper story of his dejection.

“At first he said, ‘I want to quit because nothing is gonna happen for my boxing career,'” remembers Marybeth, with whom Jonathan has three sons, ages 7, 4 and 2. “And then he realized that he would because he has kids who need a better future.

“I told him, ‘You [will] be a world champion. Not now, but coming soon.'”

*

Taconing first started boxing at age 14, earning between 300-500 pesos ($6-$10 USD) for amateur fights during town fiestas in Siocon in the province of Zamboanga del Norte.

One of six children born to parents who farmed corn and rice, Taconing competed as a swimmer before dropping out of school at 15 to work as a stock boy for a rice vendor. His monthly salary was 1,500 pesos, or approximately $31.

With financial assistance from a friend, Taconing arrived in Manila at age 19 looking to box. He lived for a short time at a school in Quezon City before being told of the Elorde Boxing Gym, the same gym built by the late Filipino boxing legend Gabriel “Flash” Elorde in 1978, in the same complex that Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier laid the cornerstone in 1975 before their “Thrilla in Manila” showdown. It’s the same gym that Pacquiao first trained at when he arrived in Manila from General Santos City, and where an upstart Nonito Donaire once prepared for his earliest fights.

Photo by Ryan Songalia

“My father didn’t want [me to be a boxer] but I took a gamble and went [to Manila] for a boxing tryout,” said Taconing, a heavy-handed southpaw whose relentless pressure compensates for his unrefined style.

With little amateur experience to his name, Taconing showed up looking to join the Elorde stable.

“We don’t look for [amateur experience]; we just look for how he does in sparring,” says “Flash” Elorde’s son Johnny Elorde, who manages Taconing alongside his wife, Liza. “Some of them get knocked out in their first sparring [session]. But if they’re really interested, they come back.”

Taconing moved into the Elorde compound in September 2006. By February 2007, he was in the ring for his first pro fight. That fight lasted all of 58 seconds as he tore through Tinglot Perez. He lost his fifth fight by split decision but would go unbeaten for four years until the Porpramook fight, including a sixth-round stoppage of future title challenger Warlito Parrenas.

Since the Porpramook setback, Taconing has won nine straight, including stoppage wins over former title challenger Vergilio Silvano and ex-WBO junior flyweight titleholder Ramon Garcia Hirales. In his last fight, in September, Taconing outfought determined journeyman Jomar Fajardo to a 10-round technical decision win.

*

You can see it in Taconing’s eyes, but it isn’t so much what you see as it is what Taconing doesn’t see. As he laces up for the final four rounds of his 160-round sparring quota, he stares ahead with a vacancy which underlies the focus he has for this fight. But he’s had much on his mind leading up to this much-delayed opportunity.

First, Mexican promoter Oswaldo Kuchle postponed the fight from June 11 to July 2 citing a hip injury to Lopez. The Elordes suspect the delay was gamesmanship to throw off Taconing’s training. Taconing adjusted by resting for three days before resuming.

Photo by Ryan Songalia

For much of that extra training time he was dealing with a heavy heart. Taconing’s older brother Felix died unexpectedly on June 6 at age 32. Taconing hadn’t seen him in 15 years and wanted to fulfil his family duty and bury his brother. Doing so would mean leaving the isolation of Manila for a potentially chaotic atmosphere in his hometown.

He tried to compromise: stay just three days in Zamboanga with Ballaran and then come back. Everyone advised against it.

“Everybody wants him to continue with the training,” said Liza Elorde. “We told him, ‘Although we understand that family tradition is you should come home, we can’t do anything anymore. All you have to do is pray and train hard so that when you become champion, you can help the whole family, including those that was left by his brother.'”

There was another concern about Taconing coming home. His brother’s death was an unexplained one, and the family believes it was caused by kulam, or witchcraft. It’s a belief given credence by some in rural Philippine provinces, and the bereaved family didn’t want to take any unnecessary chances.

“They were saying ‘That might happen to you,'” Liza Elorde says. “The family was afraid to let him go there because they were saying ‘What if you’re here and that person who is mad with your brother thinks ‘I will also do that to Tata?'”

Taconing did what he could from Manila, sending money for the burial with a vow to visit his brother’s grave when he returns.

*

Taconing will enter the ring Saturday against a fighter who likewise came up the hard way. Lopez (27-6, 17 KOs) finally won a world title in his last fight, traveling to Japan to outpoint Yu Kimura by majority decision this past March. The 13-year ring veteran from Mexico City is five years older than Taconing at age 34 and has faced many of the top champions and contenders of the sport’s lightest weights. The only fighter to truly dominate the rugged southpaw was another Filipino, Denver Cuello, who stopped Lopez in two rounds in 2012.

“Lopez is good but we’ll see when we fight. His skills and my skills will be on display,” Taconing said.

Should Taconing win, he’d be just the second world champion from the Elorde stable, and the first since Rolando Bohol won the IBF flyweight title in 1988.

More than for fame or glory, Taconing has a sense of what he’s fighting for. That, more than anything, makes this capable boxer a dangerous one.

“Before he left he hugged his three sons tight and told them that he will go there for the fight so that he can give a better future for the kids,” said Marybeth, nervous, hopeful, confident.

Ryan Songalia is the sports editor of Rappler, a member of the Boxing Writers Association of America (BWAA) and a contributor to The Ring magazine. He can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @RyanSongalia.