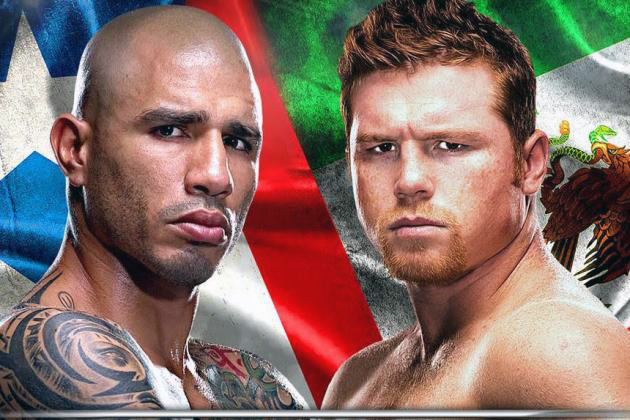

The Rivalry: Mexico vs. Puerto Rico

The following article originally appeared in the December 2015 issue of THE RING, a special double-cover collector’s edition that includes a Cotto vs. Canelo poster which is still on sale and can be purchased here.

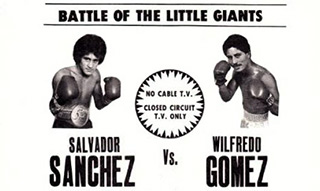

The boxing rivalry between Mexico and Puerto Rico can’t be traced to a specific origin but a convenient  starting point might be the 1981 bout between Mexico’s Salvador Sanchez and Puerto Rico’s Wilfredo Gomez, a Caesars’ Palace event dubbed by promoter Don King as “The Battle of the Little Giants.” In a way, King was casting about for his next big thing. Muhammad Ali was fading fast and Larry Holmes wasn’t the new Ali. Also, Sugar Ray Leonard wanted no part of Don King. Hence, King started focusing on the lighter weight classes, where Latin fighters had been dominant for years. WBC featherweight titlist Sanchez was a star in Mexico. Gomez, the WBC junior featherweight titlist, was an even bigger star in Puerto Rico. So King rolled the dice on his little giants and won, to the point where this bout should be considered the “big bang” of the whole Mexican-Puerto Rican argument.

starting point might be the 1981 bout between Mexico’s Salvador Sanchez and Puerto Rico’s Wilfredo Gomez, a Caesars’ Palace event dubbed by promoter Don King as “The Battle of the Little Giants.” In a way, King was casting about for his next big thing. Muhammad Ali was fading fast and Larry Holmes wasn’t the new Ali. Also, Sugar Ray Leonard wanted no part of Don King. Hence, King started focusing on the lighter weight classes, where Latin fighters had been dominant for years. WBC featherweight titlist Sanchez was a star in Mexico. Gomez, the WBC junior featherweight titlist, was an even bigger star in Puerto Rico. So King rolled the dice on his little giants and won, to the point where this bout should be considered the “big bang” of the whole Mexican-Puerto Rican argument.

The Mexican and Puerto Rican fans made Sanchez-Gomez into great television. More boisterous than a  typical U.S. fight audience, the rival groups waved flags and sang and even mocked each other’s national anthems. Meanwhile, Gomez had flown the Apollo Sound salsa band in from Puerto Rico while Sanchez answered with a group of promenading mariachis. The moment the two fighters came through the ropes, reported Sports Illustrated, “they were joined by their respective musicians in what appeared to be a ringside sock hop.” In comparison, the crowd for the Leonard-Thomas Hearns bout which took place that month in the same venue was a typical Las Vegas scene of jaded celebrity geezers. Not so for the Sanchez-Gomez mob, which was not only witnessing history but making it. Jose Torres said at the time that Americans were probably shocked by the rowdiness of the crowd but were finally seeing “our national Latino disposition.” King took notes. So did Bob Arum. The bout, won by Sanchez on an eighth-round KO, rammed home the idea that Mexicans and Puerto Ricans were a combustible combination.

typical U.S. fight audience, the rival groups waved flags and sang and even mocked each other’s national anthems. Meanwhile, Gomez had flown the Apollo Sound salsa band in from Puerto Rico while Sanchez answered with a group of promenading mariachis. The moment the two fighters came through the ropes, reported Sports Illustrated, “they were joined by their respective musicians in what appeared to be a ringside sock hop.” In comparison, the crowd for the Leonard-Thomas Hearns bout which took place that month in the same venue was a typical Las Vegas scene of jaded celebrity geezers. Not so for the Sanchez-Gomez mob, which was not only witnessing history but making it. Jose Torres said at the time that Americans were probably shocked by the rowdiness of the crowd but were finally seeing “our national Latino disposition.” King took notes. So did Bob Arum. The bout, won by Sanchez on an eighth-round KO, rammed home the idea that Mexicans and Puerto Ricans were a combustible combination.

King signed as many Latin fighters as he could find, trying to corner this new market by insisting that an African-American could relate to Latins better than any white promoter. “Blacks and Latinos are considered dummies,” he fervidly told THE RING in 1981, adding that the white world couldn’t “swallow a black man or a Latino succeeding in anything that is controlled by them.” King spent the next three decades bellowing “Viva Puerto Rico!” and “Viva Mexico!” Of course, his little Latin warriors remained secondary to his heavyweight stable but they still benefited from being part of the 1980s boxing explosion. A few even took King to court, proof that they’d finally made the big time. Arum certainly profited from Mexico and Puerto Rico, constantly reminding us that those nations, unlike America, treat boxing “like a religion.”

Nowadays the Mexican-Puerto Rican conflict is down to a predictable shtick. TV commentators grow misty eyed as they talk about “national pride” and how there is a grand tradition of Mexicans fighting Puerto Ricans. Yet, some suggest there is less to this rivalry than we imagine.

“Rivalries are constructed,” said Dr. Antonio Sotomayor, an assistant professor at the University of Illinois who is Puerto Rican and has written several books and articles on his homeland’s sports history. “Someone has to say, ‘There is a rivalry.’ The fight itself is just a fight. When you have the top two Latin nations against each other, you’d think something more is at stake. But this so-called boxing rivalry is mostly hype to sell tickets. Trust me, it means just as much when a Puerto Rican beats an American.”

Viva Mexico, indeed.

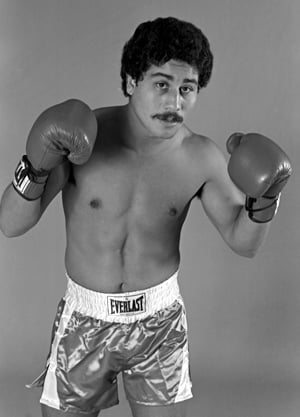

Prior to World War II, Mexicans and Puerto Ricans rarely met in a boxing ring. The fight business was mostly about New York, with Irish, Italian, Jewish and a smattering of African American fighters sharing the spotlight. Latin fighters? Why fly in a prospect from San Jacinto when you could fill out your undercard with two Italians from Flatbush? The fact that most Latin fighters toiled in the lighter divisions worked against them, too. The glamor divisions were found between welterweight and heavyweight; small Latin fighters were considered a novelty.

Granted, Mexicans and Puerto Ricans did fight each other occasionally. A 1934 bout between Sixto Escobar and Rodolfo “Baby” Casanova in Montreal saw Escobar win what local officials billed as a world bantamweight title by a ninth-round KO. When Escobar returned to San Juan schools closed for the day so everybody could greet “El Gallito” at the docks for the victory parade. A few months later Escobar traveled to Mexico City and dropped a 10-round non-title bout to Juan Zurita, a future champion from Guadalajara who would finish his career with 131 wins. But these bouts were hardly newsmakers. For the most part, Mexicans fought in Mexico and Puerto Ricans fought in Puerto Rico. It would take many years for either group to become part of the American boxing landscape. As was usually the case in boxing, it wasn’t talent that talked; it was the loud, bullying voice of economics.

The first of two key factors was California’s gradual rise as a boxing hotbed, thanks mostly to promoters like George Parnassus who packed his Los Angeles shows with Mexican sluggers. With an eye on the money to be made in California, Mexican fighters seemed to appear as if they were being created on an assembly line. Concurrently was “the Great Migration” of Puerto Ricans to New York during the 1950s. As the number of Puerto Ricans in New York increased, promoters and managers searched for fighters from the island to showcase in local arenas. Ta-daaa! By the 1960s, two of boxing’s most popular champions – Carlos Ortiz and Jose Torres – were Puerto Rican. This was part of the “Latin boxing boom” where fighters from various Spanish-speaking countries began winning title belts, aided in no small way by Parnassus, who helped establish and finance the WBC in 1962 in part so his Mexican imports could fight for newly created titles.

As each group grew in numbers, it was inevitable that Mexicans and Puerto Ricans would meet more frequently in the ring. The results were almost always notable because the fighters of each group are generally straight-ahead punchers who give no quarter. You’ll find some slick boxers from each side but, for the most part, Mexican and Puerto Rican fighters like to bang it out. As Miguel Cotto said many years ago before meeting Antonio Margarito, “If you put one Puerto Rican fighter in front of a Mexican fighter, you’re going to see a good fight.”

The late Torres once surmised that the competition was less about Mexicans vs. Puerto Ricans than it was about all Latin fighters and how a certain familiarity between the groups gave these matchups extra fire. “You see,” Torres told THE RING in 1981, “we know each other. We know how to intimidate each other. And we know how to resist it. But we are very dramatic in the process. Some of us even get violent, a luxury we seldom (reveal in front of) the gringo.”

And the customers give the bouts an added kick.

“Latin fans attend boxing matches as if they’re part of a performance,” Dr. Sotomayor said. “It’s a celebration of being part of a prime event at a time when Puerto Rico and other Latin countries aren’t prime (in terms of economics). We may boo a Mexican fighter but that’s the role we play in the audience. It’s festive, it’s theater.”

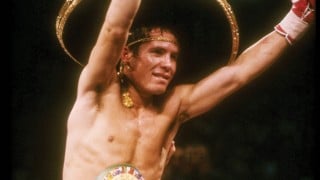

There have been times, though, when the trash talk took on an uglier dimension. This was especially true of Julio Cesar Chavez’s heyday, when he seemed to be dusting off a different Puerto Rican opponent every month. After beating Hector Camacho, Chavez said he wouldn’t be allowed to return to Mexico had he lost. Perhaps more than any other fighter, Chavez made the rivalry feel real. But was the trash talk just good old-fashioned pre-fight banter? Or did it go deeper? Is there a sociological slant to all of this? Is it to do with Puerto Ricans being free to enter the United States as they please while Mexicans are not? When a Mexican whips a Puerto Rican in the ring, is he symbolically striking a blow against America?

There have been times, though, when the trash talk took on an uglier dimension. This was especially true of Julio Cesar Chavez’s heyday, when he seemed to be dusting off a different Puerto Rican opponent every month. After beating Hector Camacho, Chavez said he wouldn’t be allowed to return to Mexico had he lost. Perhaps more than any other fighter, Chavez made the rivalry feel real. But was the trash talk just good old-fashioned pre-fight banter? Or did it go deeper? Is there a sociological slant to all of this? Is it to do with Puerto Ricans being free to enter the United States as they please while Mexicans are not? When a Mexican whips a Puerto Rican in the ring, is he symbolically striking a blow against America?

“There’s always more than just competition in sports,” said Dr. Sotomayor.

Yet Dr. Dain Borges, a professor in the University of Chicago’s Mexican Studies program, doesn’t see the much-hyped rivalry as being rooted in anything political.

“It just feels like a college rivalry that builds up over the years,” Borges said. “There’s certainly no historical reason for it. Mexicans and Puerto Ricans know each other through pop music and movies. There’s not a lot of interaction between the two. Any sort of rivalry is inexplicable.”

If anyone is keeping score, Mexico has created far more fighters, more champions and more Hall of Famers than the much smaller Puerto Rico and proudly guards its reputation as the top Latin boxing group. Still, there’s always a sense that this “feud” goes beyond wins and losses and belts.

“These fighters,” said Dr. Sotomayor, “are carrying the weight of nations in their hands. And to Latin people, the fighter represents the daily struggle of dealing with life. The symbolism of a boxer is very different from a baseball player. He’s a fighter. There’s more identification.”

Yet, this intense audience identification doesn’t manifest in the sort of dark emotions one might find at a Yankees-Red Sox game. To hear Dr. Sotomayor tell it, just being in the arena is a victory of sorts. “The attention is on us, and we show exuberance. In the end, the Puerto Rican doesn’t go home heartbroken if our fighter loses. We’re happy to be present. We showed that we exist. Even when the promotions rely heavily on stereotypes, about how Latin people are ‘hot blooded’ and violent, we put up with the stereotypes in order to be part of these special events. Maybe someday we’ll look at this differently and wonder if the negatives outweigh the positives.”

Oh, Sixto Escobar, what have you wrought?

“The bigger picture,” Dr. Sotomayor said, “is that Puerto Rico and Mexico have a lot of respect for each other. There’s no real blood rivalry. If a Mexican is fighting an American, the Puerto Rican fan will root for the Mexican.”

So what precisely does it mean when we see a Mexican and a Puerto Rican fighting in a ring more than three decades after Sanchez-Gomez? It means Mexico and Puerto Rico remain poor and their young people still turn to boxing as a way out. It means the promoters who felt these Latino bombers were worth showcasing were correct, even if their motivations were not exactly unselfish. And it means we’ll probably get a memorable fight. Besides, it’s easier than drumming up a feud between Canada and Sweden.