10: Notable middleweight title bouts between sluggers

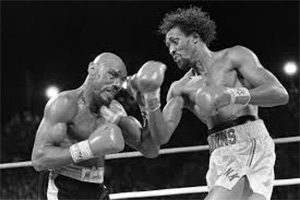

Photo by Naoki Fukuda

Boxing may be known as “The Sweet Science” but at its core it’s a sport whose appeal is fueled by its hardest punchers. It doesn’t matter whether the power emanates from exquisite technicians like Sugar Ray Robinson, Joe Louis, Alexis Arguello and Ricardo Lopez or from cruder practitioners such as Rocky Marciano, Stanley Ketchel, George Foreman (the younger) or Rocky Graziano, the fact that any of their fights could end at any moment gave their bouts a unique edge-of-your-seat suspense. That wondrous sense of tension and expectation caused tickets to fly from the box office, TV ratings to soar and, in this modern age, pay-per-view sales and web site clicks to surge.

The thrill of seeing a genuine puncher fight anyone is exciting enough, but a contest that pits two big-time sluggers raises the bar to another level. Then there are fights like Saturday’s showdown between Gennady Golovkin and David Lemieux. Not only are they among boxing’s hardest shot-for-shot fighters – they have a combined 61 KOs in their 67 wins – they each hold a version of the middleweight championship and they share a predatory mindset. Better yet, they also are meeting at their respective zeniths; the 26-year-old Lemieux is coming off a career-best win over Hassan N’Dam that won him the vacant IBF belt this past June while “GGG,” still a massive force at age 33, notched his 20th consecutive knockout in May against Willie Monroe Jr.

Ever since the first middleweight title fight between Jack “The Nonpereil” Dempsey and George Fulljames in July 1884, there have been precious few championship bouts that paired two genuine bombers. The following article will recount 10 such contests in chronological order. Some more than lived up to the press clippings that preceded them while others qualify as “Closet Classics.” Still others were shootouts that stuffed a 12-rounder’s worth of thrills into a compressed space.

Without any further delay, the list:

Bob Fitzsimmons KO 2 Dan Creedon – Sept. 26, 1894, Olympic Athletic Club, New Orleans

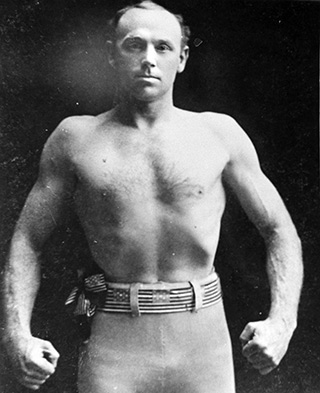

With 156¾ pounds spread over his 5-foot-11¾-inch frame, the balding and heavily freckled “Ruby Robert” certainly didn’t look like one of boxing history’s most explosive hitters. One look at his massive blacksmith’s shoulders, however, said all there needed to be said about why Fitzsimmons’ last 37 victories had come by knockout and why he was riding a 14-fight KO streak going into the Creedon fight. Every punch Fitzsimmons landed did so with elephantine impact and it didn’t matter what part of his opponent’s anatomy it struck; once Fitzsimmons hit you, you stayed hit.

Photo from THE RING archives

According to an article published in the October 13, 1894 edition of The National Police Gazette, Fitzsimmons often felt the need to hold back his power and let fights last several extra rounds in order to please the spectators. When he fought Arthur Upham in July 1890 – Fitzsimmons’ first appearance in New Orleans – the reporter speculated that Fitzsimmons could have easily disposed of his foe in the first round but instead allowed the contest to go into the ninth before finishing the job. But when he felt an opponent posed a serious threat, as was the case nearly three years later against Jim Hall, again in New Orleans, Fitzsimmons took no chances and ended the match at the first opportunity, which, in this case, occurred in round four.

Fitzsimmons, who was making the first defense of the title he won more than three years earlier from Dempsey, dearly wanted to prove himself worthy of a crack at James J. Corbett’s heavyweight championship and he wanted to use the Creedon fight to make his case.

As for Creedon, 15 of his 19 wins had come inside the distance, and like Fitzsimmons he was in the midst of a nice KO run as he had gone 10-0-1 (8) in his last 11 contests. Creedon had maintained a breathtakingly active schedule as the Fitzsimmons bout represented his eighth fight of 1894, a year that saw him fight five times in February alone. Though four inches shorter than Fitzsimmons, Creedon was confident his body punching would cut the champion down to size.

“At 158 (then the middleweight limit) I don’t see where any man in the world will have any advantage over me,” the 26-year-old said. “The talk about Fitz outclassing me with his height and reach remains to be seen. I’ll show the knowing ones that the unexpected sometimes happens, and this is to be one of the times. I am in championship form and could not be fixed up better for any fight.”

Perhaps he heard the rumors surrounding Fitzsimmons’ badly swollen knee and an abscess in one of his ears thanks to the artesian well water in the club’s swimming pool. Though his knee sported a nickel-sized sore spot, the abscess reportedly broke during his run the previous Sunday, which prompted Fitzsimmons to proclaim himself fit.

“My knee is all right and I am all right,” the 31-year-old champion declared. “I am satisfied with my condition and will be as good as I ever was in any fight before. I have trained hard for this bout, and I think I will win. I know Creedon is a hard puncher, and I do not hold him cheap at all. He is a good man, but he just cannot beat me; that is all there is to it. I am going to win, and will do it as quick as I can.”

Creedon entered the ring at 9:07 p.m. with Fitzsimmons following immediately after. Ten minutes later, the fight was on.

The contest began at a ferocious pace with Creedon attacking Fitzsimmons’ flanks and the champion using his height and reach to hold him off. In one of the clinches Fitzsimmons blasted a right uppercut to the jaw while Creedon dug a right to the ribs. As the round closed Fitzsimmons landed two heavy rights to the ear, then a one-two to the face.

Creedon started the second by jabbing Fitzsimmons’ face only to be floored by a vicious counter right. Creedon remained on a knee for an eight count, then nodded to show the official he was still in control of himself. Fitzsimmons drove both fists into Creedon’s face, causing the challenger to desperately hold on. The champion punched his way out of Creedon’s grip, then landed a pair of hooks to the jaw that left Creedon spread-eagled on the canvas. Creedon was counted out at 2:40 of round two and he remained on the canvas for at least five minutes more. Once order was restored Fitzsimmons issued a challenge to Corbett to fight him for the heavyweight title, the Police Gazette “Diamond Belt” and $10,000 a side.

Within 10 minutes, the owner of the Olympic Club sent a telegraph to Corbett with an offer of $25,000 to meet Fitzsimmons. The pair wouldn’t meet for another two-and-a-half years but when they did, history was made as Fitzsimmons became the first former middleweight champion to become heavyweight king thanks to his “solar plexus punch.”

(Special thanks to the Gazette’s William A. Mays for providing the article that recounted this bout)

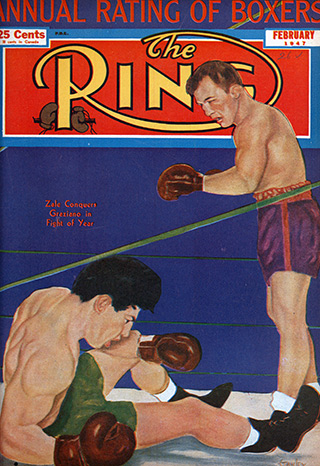

Tony Zale KO 6 Rocky Graziano I – Sept. 27, 1946, Yankee Stadium, New York, N.Y.

Zale was making the first defense of his middleweight title after a four-year hiatus forced by World War II and he couldn’t have asked for a more draining, demanding fight than the one he ended up getting from the snarling bomber from New York’s East Side. Though Zale had knocked out all six non-title opponents, each within five rounds, during his post-war comeback in 1946, it was Graziano who was installed as the slight betting favorite thanks to his sustained activity and a eight-fight winning streak that included seven knockouts, the latest of which came six months earlier against former 147-pound champion Marty Servo (KO 2).

Zale’s crunching left hook accounted for most of the 35 KOs in Zale’s 57-16-2 record while the majority of Graziano’s 32 knockouts in his 43-6-5 ledger resulted from a wicked right cross that was rarely thrown in a straight line. While their personalities were in direct conflict, the business-like Zale and the gregarious Graziano each were seek-and-destroy hitters of the first order.

Cover from THE RING archives

Chaos reigned from the echo of the first bell as Graziano stormed out of his corner only to be dropped by the champion’s trademark left hook. The challenger fought his way out of the fog and scored his own knockdown in round three with a long right to the chin. Most of the 39,827 that saw the fight first-hand roared for their hometown hero to finish the champion and over the next three rounds he tried to break the “Man of Steel.”

“The crowd is yelling and they’re clapping,” Graziano wrote in his autobiography. “They want blood. They want the kill. They paid to see the wild, filthy-mouth, dirty-punch East Side Guinea punk knock out the champion from Indiana who was built of steel like the mills he come from. That’s what the papers told them they were going to see. All right. All right. Just give me some wind, give me my breath back and get the sweat rubbed off, and I will give them what they paid for.”

But the ultra-tough Zale took everything the 24-year-old Graziano dished out and managed to land his share of soul-sapping body shots. Still, the effort drained the 32-year-old champion to the point of near collapse and after the fifth round bell he started to walk toward the wrong corner. For all the world it looked as if the fight would end in round six and in this case the world was right. However, it was Zale, not the surging Graziano, who got the job done.

A monstrous hook to the body decked Graziano early in the sixth, a punch from which the challenger managed to rise. He wouldn’t be so fortunate after he absorbed a shattering hook to the jaw moments later. Graziano remained on a knee for the count, jumping to his feet only after referee Ruby Goldstein counted “10.” At 1:43 of round six Zale had pulled himself out of the fire and walked out of the ring the winner and still champion while the disappointed challenger could only stew about how close he had come to fulfilling the ultimate dream.

Graziano’s stirring challenge fueled instant demands for a second act, and after getting past some formidable red tape, those demands would be granted.

Rocky Graziano KO 6 Tony Zale II – July 16, 1947, Chicago Stadium, Chicago, Ill.

The rematch was originally scheduled for March 21, 1947 at Madison Square Garden but on Feb. 7 the New York State Athletic Commission revoked Graziano’s license and threatened to bar him for life for his failure to report a $100,000 bribe to intentionally lose to Reuben Shank, a fight that was canceled after Graziano claimed a back injury. Though a grand jury threw out the case due to a lack of evidence, the NYSAC held firm. Influential sports writers such as Bill Corum and Red Smith supported Graziano in print and combined with a wave of public support – as well as the other commissions around the country not following New York’s lead – the rematch was green-lighted in Illinois.

A crowd of 18,547 set a new record for the largest gate for an indoor fight – $422,918 – and the ensuing action was worth every penny. This time, however, it was Zale that tore into Graziano as he opened a gash over the challenger’s left eye in round two and dropped him with a potent right in the third, a round Graziano described as “the worst round I ever lived through in the ring.” Graziano’s personal hell continued as Zale’s short, pinpoint blows swelled Graziano’s right eye shut by round four. All seemed lost.

But in round five Graziano dug deep and found an extra reservoir of energy, an energy borne of desperation and fury. The New Yorker’s murderous blows from both hands drew loud “oohs” from the fans and the smothering heat only heightened the intensity of their pitched battle.

“I got a second wind, like a breeze of cool air come from heaven,” Graziano wrote in his biography. “I sucked it deep in my lungs and I felt new strength tingle down my arms and legs and I yelled that I was going to kill that stinking rat bastard. I tore into him and I never stopped.” Only the round-ending bell had the power to save Zale – but only for 60 seconds.

The sixth was Zale’s apocalypse and Graziano’s perfect storm. The challenger’s relentless attack had Zale reeling around the ring and though the aging warrior tried his best to stem the tide Rocky’s roll was too much to overcome. A torrent of blows caused Zale to collapse over the center rope, prompting referee Johnny Behr, who had once been the boxing coach for the 1936 U.S. Olympic team, to stop the contest.

Graziano-Zale II was deemed THE RING’s 1947 Fight of the Year and to this day it remains one of the most sensational middleweight title fights ever waged.

Sugar Ray Robinson KO 3 Rocky Graziano – April 16, 1952, Chicago Stadium, Chicago, Ill.

Graziano lost the title back to Zale in June 1948 in the most lopsided fight of their trilogy, after which Zale lost the belt to Marcel Cerdan, who lost it to Jake LaMotta and who lost it to Robinson, still considered by many the greatest fighting machine who has yet lived. Since losing to Zale Graziano went 20-0-1 with 17 knockouts, the best wins coming against Charley Fusari (a come-from-behind KO 10) and a pair of victories over Tony Janiro (W 10, KO 10) after Janiro affixed the lone draw on Graziano’s current run. Just 20 days before meeting Sugar Ray Graziano polished off Roy Wouters in one round.

Robinson was making the third defense of his second reign; for after beating LaMotta for the belt he shockingly lost a lopsided 15-round decision to Randy Turpin in London, the final fight of a six-fight European swing in the late spring and early summer of 1951. The rematch was staged just 64 days later at the Polo Grounds in New York and through nine rounds the fight was even. When Turpin opened a dangerous cut over Robinson’s left eye, the American legend unleashed a desperate rally that dropped Turpin. After the champ arose at nine Robinson trapped Turpin on the ropes and belted him with a remorseless barrage that persuaded referee Ruby Goldstein to stop the contest. The TKO win was the 85th of Robinson’s career, once again proving that this master boxer also had dynamite in each fist.

Six months later Robinson out-pointed Carl “Bobo” Olson over 15 rounds to raise his record to an extraordinary 130-2-2 with one no-contest, then accepted a match with Graziano that was slated to take place just 34 days later at Chicago Stadium, the site of Graziano’s greatest triumph nearly five years earlier and also the venue where Robinson dethroned “The Raging Bull.”

As is the case with most Graziano fights, the action was fierce and riveting. Robinson’s needle-sharp boxing and whistling combinations won the first round, though one Graziano right hand briefly stunned the champ, while Graziano’s sporadic but power-packed punches helped him win the second round on the referee’s card and an even call from one of the judges.

The pair exchanged heavy punches to start the third but Robinson appeared to seize the upper hand when a combination drove Graziano across the ring. The moment Graziano’s back hit the ropes he unleashed a wild right hand that caught Robinson on the neck and scored a flash knockdown. The champ rose immediately and seemed in full control. Seconds later, he nailed Graziano with a right cross followed by a left uppercut. Robinson then spun away from the ropes and blasted Graziano with a four-punch volley capped by a TNT right to the jaw that sent the challenger’s mouthpiece flying and his body crumbling in sections. At seven the dazed Graziano kicked his right leg in order to get some semblance of life back into it, but that would be it as referee Tommy Gilmore counted him out.

“I feinted the right to the body and I hit him on the chin,” Robinson told blow-by-blow man Steve Ellis.

“The count went too fast,” Graziano said in the dressing room. “I thought I had time to get up but my legs were gone. Shouldn’t have been down anyhow, you know? I had the guy right there and waited too long to throw the right. Geez, how much an imbecile can a guy be? Just a dumb fighter, me. One second I’m winning, the next I’m hearing ’em count. Boy, the guy can belt! A great fighter.”

Rodrigo Valdez KO 7 Bennie Briscoe II – May 25, 1974, Stade Louis II, Fontvielle, Monaco

From November 1970 to the spring of 1975 Carlos Monzon had reigned supreme over the middleweight division but when his management team failed to reach a deal to fight Rodrigo Valdez the WBC withdrew its recognition and arranged to have Valdez meet Bennie Briscoe for the vacant title. This was a rematch of a bout held the previous September in which Valdez won a comfortable 12-round decision for the North American Boxing Federation belt. Despite the head-to-head win, Valdez was the WBC’s third-ranked middleweight while Briscoe occupied the number-two slot.

Valdez entered the contest on a 20-fight winning streak that lifted his record to 50-4-2 (34). That string included 16 knockouts and, at one point, 11 in a row. Following the points win over Briscoe Valdez began a new KO string with two-round blowouts of Joey Durelle in December 1973 and Eddie Burns in March 1974.

Briscoe, a shaven-headed slugger from Philadelphia, was one of his era’s most feared campaigners because of his toughness, fearlessness, punishing body punching and a left hook straight from Hades. Yes, his 46-11-1 (42) record wasn’t the glossiest to look at but it was a record built on a solid foundation. Some of the quality names on his ledger included Stanley “Kitten” Hayward (10-round split decision loss), George Benton (KO 9), Luis Rodriguez (L 10, L 10), Vicente Rondon (L 10), Tom “The Bomb” Bethea (KO 6), Billy “Dynamite” Douglas (KO 8) and Tony Mundine (KO 5). But the biggest name of all was that of Monzon, and in their 25 rounds spread over two fights “Bad Bennie” gave the 160-pound monarch all he could handle. In May 1967 Briscoe affixed the seventh draw of Monzon’s 50-fight career and more than a few believed the American should have flown out of Argentina with a victory. They met again for Monzon’s championship in November 1972, again in Buenos Aires, and Briscoe’s best moment came in the ninth when his power threatened to dethrone “King Carlos.” But Monzon rode out the storm and won a sizable 15-round decision.

Since the Valdez loss Briscoe notched knockouts over Ruben Roberto Arocha (KO 3), Willie Warren (KO 7) and Mundine (KO 5). The Mundine stoppage was the 22nd straight time Briscoe gained a victory inside the distance and as he stepped into the ring inside the Stade Louis II in Monaco he knew that the knockout was his most likely path to victory. Both were finely conditioned as Valdez scaled 157¾ to Briscoe’s 156¾.

The fight began as expected; Valdez circling behind the jab and Briscoe bobbing in, winging hooks and attacking the body with both hands. Briscoe hoped to exploit Valdez’ tendency to start slowly, a habit so chronic that trainer Gil Clancy said before the fight that he wanted to jump in the ring and prod his fighter into action. It happened again here; while Valdez landed jabs flush to the face and landed an occasional hook, Briscoe successfully cut off the ring, landed heavily to the ribs and connected with several right uppercuts to the jaw.

Midway through the round, however, Valdez’s prodigious power struck as a compact right suddenly sent Briscoe staggering back toward mid-ring. Valdez pounced on Briscoe but because the storm was short-lived the American’s head cleared and by round’s end he was banging Valdez’ body with abandon.

The pair traded violently along the ropes to open the second but whenever the action moved back to long range Valdez’s hand speed and pinpoint punches held sway. While Valdez’s punches carried more sting and affected Briscoe more than Briscoe’s shots impacted Valdez, Briscoe’s thudding blows landed frequently and heavily.

Valdez opened the third on his toes and in this posture Valdez’s advantages in hand speed, mobility and punch variety were obvious. Though Briscoe still landed to the body, Valdez smartly clinched at every opportunity. Valdez’s punches brought a trickle of blood from Briscoe’s nostril but that didn’t stop the Philadelphian from scoring with head-body combos in the round’s final moments.

Valdez continued to box well in the fourth and though Briscoe successfully drew the Colombian into vigorous exchanges from time to time Valdez did no worse than even during those sequences. Still, Briscoe opened a small cut near Valdez’ left eye. Valdez responded by driving Briscoe back with a two-fisted assault, an assault from which Briscoe bounced back quickly.

Little by little, the gap between Valdez and Briscoe widened as his peppery combinations visibly affected Briscoe while the Colombian handled his opponent’s body shots with aplomb. The pace remained furious, but while Briscoe was good, Valdez was better.

The sixth was Valdez’s most dominant since the first as his piercing blows repeatedly found the target. Still, Briscoe landed enough punches to intensify the amount of blood flowing from Valdez’s eye cut.

Briscoe rallied early in the seventh as he landed a heavy right to the injured eye that sparked a volley of blows. But then Valdez turned the tables with a single punch.

A split-second after Valdez missed with a wild left hook Briscoe just missed with a straight right to the chin. As Briscoe threw next punch Valdez cranked a short right hand that struck the point of Briscoe’s chin with explosive force. The punch immediately froze Briscoe’s body, then sent it tumbling back-first to the canvas. Briscoe somehow tottered to his feet at referee Harry Gibbs’ count of five but the sight of Briscoe’s shaky frame prompted the British official to call a halt. Only four seconds remained in the round, and it would be the only KO loss of what would be Briscoe’s 20-year, 96-fight career.

Stable mate Emile Griffith, who earlier scored a 10-round decision over Renato Garcia, was one of the many who raced into the ring to congratulate the new WBC titlist. Entering the seventh, Valdez was in command on the scorecards (59-57, 59-56, 60-55), a score line that didn’t adequately illustrate the pulsating two-way action that took place inside the ring.

Marvelous Marvin Hagler KO 3 Thomas Hearns – April 15, 1985, Caesars Palace, Las Vegas

Like Frazier-Ali I before it, Hagler-Hearns was a matchup so good that it didn’t need a fancy nickname to sell it to the public. “The Fight” sufficed, and a fight was exactly what the public received.

True, Hagler and Hearns possessed too many other gifts to be considered pure sluggers but their knockout records spoke loudly of their power. “Marvelous” Marvin boasted 50 knockouts in his 60-2-2 record and of his 10 previous title challengers only one – Roberto Duran – managed to make it to the final bell. Hagler’s vast toolbox of talents – mobility, an educated right jab, excellent body punching, above-average defense and a ferocious work ethic – were more than enough for his opponents to deal with but when one added his power-laden fists the package was nearly unconquerable.

The same could be said of Hearns, who began his career with 17 straight knockouts and was aspiring to add the middleweight crown to his belts at 147 and 154. Before his WBC super welterweight defense against Duran – a fight that would have been a unification match had the WBA not stripped the Panamanian for not fighting Mike McCallum – “The Motor City Cobra” announced he had once again become “The Hit Man” and vowed to destroy “The Hands of Stone” in two rounds. To the world’s shock Hearns lived up to his promise, flooring Duran three times and sending him face-first to the canvas with one of the greatest right crosses ever thrown. Hearns followed up that sensational victory with another as he crushed Fred Hutchings in three rounds, then promised to knock out Hagler in the same round.

Hearns was a physical marvel – his 6-foot-1 frame featured a massive 78-inch reach and thanks to the tutelage of Emanuel Steward the amateur that had scored just 12 knockouts in 163 amateur fights became one of boxing history’s most terrifying knockout artists. Entering the bout Hearns’ record stood at 40-1 (34) and if anyone had the power to crack Hagler’s cast-iron dome it was he.

After out-pointing Duran, Hagler struggled in the early rounds against Argentine strongman Juan Domingo Roldan before either an uppercut or a thumb swelled the challenger’s eye shut and led to a 10th-round TKO. But any whispers about Hagler’s potential erosion were erased nearly seven months later when he took out Mustafa Hamsho in three rounds.

The intensity during the pre-fight festivities suggested that mayhem was about to ensue. But while many fights appear to crackle with potential beforehand the action that follows often falls short of the mark, especially when the match involves two genuine boxer-punchers with many strategic options at their disposal.

Hagler and Hearns, however, not only followed up they throttled up. Big time.

Hagler charged out of his corner behind a sweeping right hook that missed and a left to the body that didn’t while “The Hit Man” tried to establish a long-range fight behind his jab. Seconds later a heavy right hook landed on Hearns’ chin and Hearns retaliated with a sizzling right cross that caused Hagler’s legs to dip momentarily. That sequence lit the fuse on what would be a historic firefight that would last for the remainder of the round.

Both fighters’ anatomies suffered under the strain of their mutual combat. Hearns broke his right hand on Hagler’s skull while Hearns’ shredding punches opened an angled gash on the champion’s forehead. Every punch Hearns landed sent sprays of crimson but Hagler’s crisp and compact offerings caused Hearns’ body to shudder. At round’s end each man looked over his shoulder and fired a glare at his opponent while the electrified crowd roared in raw, unvarnished rapture.

With his greatest weapon damaged, Hearns returned to his amateur boxing roots and tried to keep Hagler at arm’s length with his snaking jabs. The stress of round one could be seen in Hearns’ legs, which, at one point, buckled as he tried to pivot hard to his left and in his right hands, which were no longer thrown with full force. The snorting Hagler walked through Hearns punches and shook the challenger with snappy, straight-from-the-shoulder blows.

The third started well for Hearns as his jabs aggravated Hagler’s cut to the point that blood was covering his face. At that point referee Richard Steele summoned Dr. Donald Romeo to examine the gash.

“It’s not bothering his sight,” Romeo told Steele. “Let him go.”

Fearing his titles were in mortal jeopardy, Hagler shifted into overdrive. A stiff jab and a booming right rocked Hearns to his core and another right jerked the challenger’s head. Hearns continued to box but it was becoming obvious that his efforts to hold Hagler at bay would be futile.

After Hearns poked out a weak jab Hagler sprung out of his crouch and blasted an arcing overhand right to the temple that rubberized the challenger’s legs. As Hearns loped away toward ring center Hagler chased after him, landed a second right, whiffed on a good-night hook and blasted a crushing right to the side of the face. The semi-conscious Hearns first slumped onto Hagler’s shoulder, then slid down the champion’s body until hitting the floor with a thud.

Hearns’ glazed eyes suggested he was out but by Steele’s count of six he began to stir. Incredibly he pulled himself upright by nine, but his tottering body told Steele that Hearns was no longer fit to fight. At 2:01 of round three, Hagler’s ultimate triumph – and Hearns’ second megafight disappointment – was made official.

At long last, Hagler achieved the mainstream acclaim for which he had hungered. Hearns, however, would have his day in the sun.

Thomas Hearns KO 4 Juan Domingo Roldan – Oct. 29, 1987, Las Vegas Hilton, Las Vegas

Even before Hearns captured his first major title at age 21, he had a long-range goal that would separate him from all who had ever fought before him: Becoming the first boxer ever to win titles in four weight classes. The feat had been attempted twice before by Henry Armstrong and Alexis Arguello; “Homicide Hank” was derailed by questionable judging when his middleweight title fight with Ceferino Garcia was judged a draw while Arguello had the misfortune of twice fighting a peak Aaron Pryor.

Hearns was three-quarters of the way to his goal as he won the WBA welterweight title from Pipino Cuevas, the WBC super welterweight title from Wilfred Benitez and, in his most recent outing, the WBC light heavyweight belt from future stable mate Dennis Andries. At 173¼, Hearns’ body was fuller yet impressively chiseled and the six knockdowns he scored proved beyond doubt his power would follow him up the scale. He said immediately after the fight that light heavyweight “was the weight for me” but now, in order to complete his mission, he needed to sweat down to 160 without compromising his strength.

And he would need every bit of that strength, for Roldan was arguably the strongest middleweight on the planet. The stockily-built Argentine was nicknamed “El Martillo,” – “The Hammer” – for his prodigious overhand right, a punch he landed time and again when he fought Marvelous Marvin Hagler more than three years earlier. Since then Roldan campaigned at light heavyweight and super middleweight, winning 13 straight and eight by KO. Save for an eight-round decision against Andre Mongelema in Monaco and a ninth-round TKO over James Kinchen two fights earlier on the Hagler-Leonard undercard in Las Vegas all of Roldan’s bouts were in Argentina. In some ways the Hearns fight was a full-circle moment; for the second time he would be pursuing the middleweight title in Las Vegas against a pound-for-pound superstar. A freakish eye injury prevented him from knowing whether he was good enough to pull the massive upset against Hagler; now he had a second chance to prove his worth, and it was coming against a fighter who also was conquered by “The Marvelous One.”

The opening bell saw Roldan fly out of the corner and unleash the wild, overhand swings that had been so successful against Hagler. Hearns handled the situation with the icy assurance of a “Hit Man,” then issued his response in the form of two quick overhand rights that dropped Roldan just 57 seconds into the fight. Up at three, Roldan took referee Mills Lane’s mandatory eight, then fearlessly returned to the fray.

Roldan’s right began connecting with regularity, prompting Hearns to slap on useful clinches. An instant before the bell, Hearns landed a lead right that scored a second knockdown. With no saving by the bell, Roldan had to get up at six before being allowed to walk to his corner.

When Hearns dropped Roldan a third time with a hook seconds into round two, it looked like Hearns’ historic coronation was just seconds from commencing. The odds looked extremely long for Roldan, for he still had to survive two-and-a-half more minutes of pounding before earning another rest. Up at three, Roldan again charged at Hearns while the American was content to keep his distance with his legs and his seemingly endless reach.

Forty seconds into round three Roldan landed a solid right followed by a right-left-right that wobbled Hearns and inspired Roldan. The South American’s attack was relentless and it took every bit of Hearns’ skill and will to survive. As it was the exertion took a lot out of Hearns, who was breathing heavily as he plopped on his stool.

“Get out and box him a little bit more,” Steward told Hearns. “You’re going to run yourself out of gas because you’re going too damn fast.”

Hearns may have wanted a breather, but Roldan refused to give him one. A massive hook shook Hearns to his foundations and only excellent upper body movement along the ropes prevented him from sustaining even more damage. His head clearing within seconds Hearns instantly turned the fight with a right to the forehead that nailed the charging Roldan. Moments later, a signature Hearns right to the jaw floored Roldan for the fourth – and final time.

Lying face-down at ring center, Roldan could only roll onto his back before Lane completed the count. As he did so a triumphant Hearns pumped his fist, stomped his foot on the canvas and threw both arms skyward.

For Hearns history had been made and he took special pride that this history was something neither Hagler nor Leonard could claim.

“I have done something no other man has ever done,” he said. “Even the two men that defeated me – Marvin Hagler and Ray Leonard – I know they are looking at me now, they want to come back and do it again. There’s got to be a way.”

There would be no rematch with Hagler, but nearly 20 months later Hearns and Leonard would meet again in a fight that was even more action-packed than the original. Although Leonard would go on to win titles in a fourth and a fifth weight class just three days after Hearns won his fifth divisional belt, Hearns will always have the distinction of being first.

Nigel Benn KO 1 Iran Barkley – August 18, 1990, Bally’s Las Vegas, Las Vegas

Two years earlier THE RING had declared Benn the hottest prospect in boxing because his nuclear-tipped fists obliterated his opponents with alarming dispatch. “The Dark Destroyer’s” all-out attack registered 22 consecutive knockouts before Michael Watson’s wily tactics resulted in Benn’s lone defeat, a sixth-round TKO that was as much about Benn’s exhaustion as about Watson’s considerable skills. The wiser Benn altered his approach in the ring and out – he changed trainers, moved to Miami and incorporated more defense into his game – and the result was a four-fight winning streak that saw Benn impressively dethrone WBO titlist Doug DeWitt by eighth round TKO less than four months earlier. Entering the Barkley fight, Benn’s record was an enviable 26-1 (24).

The choice for Benn’s first defense appeared, on paper, to be a calculated but prudent risk. Yes, Iran Barkley was a well-known former middleweight titlist armed with a deadly left hook, a street fighter’s mentality and a ferocious will to win. However, those assets were counterbalanced by several negatives: (1) he had lost his last two fights by decision to Roberto Duran, then Michael Nunn, which dropped his record to 25-6 (16); (2) the Nunn fight took place more than a year earlier – he underwent surgery for a detached retina the previous December – and Barkley’s brows were notoriously brittle; (3) Barkley ballooned to 217 pounds during his long hiatus and worst of all, (4) Barkley’s father passed away just six days before the Benn fight. Thus, Benn was installed as a 9-to-5 favorite.

The war was on even before the echo of the bell had died down as Benn nailed Barkley with a long lead right to the chin that snapped back the challenger’s head and forced his arms to lock in a tight and extended clinch. Then, just 13 seconds into the fight, a right to the ear caused a stunned Barkley to turn toward the ropes and a follow-up hook to the jaw dropped the challenger. As referee Carlos Padilla jumped between them a wild-eyed Benn winged a right over the referee’s shoulder and hit Barkley’s temple. Padilla scolded Benn in the neutral corner while Barkley unsteadily awaited the return to action.

Once it did, the high-octane war continued apace. Benn trapped Barkley on the ropes and whaled away while Barkley responded in kind, albeit with slower and lethargic punches. But as the fight neared the one-minute mark Barkley caught Benn with a hook to the jaw that forced the champion to beat an instant retreat. Two more hooks along the ropes snapped Benn’s head and now it was the champion who was affixing an iron grip. Once separated Barkley continued to rally behind a snappy one-two and a left uppercut that sparked a “Barkley! Barkley!” chant from the partisan crowd.

But then, the tide turned again. With 1:12 remaining Benn nailed Barkley with a huge right to the chin, then an equally hurtful right uppercut. Barkley, determined not to be outdone, then rallied back with several of his own bombs.

The back-and-forth action had the spectators in a frenzy and it became obvious that the services of judges Chuck Giampa, Dave Moretti and John Rupert wouldn’t be necessary. In fact, they didn’t even have to pick up their pencils.

With a little more than 30 seconds remaining in a wild opening session Benn connected with an overhand right and a whistling hook that caused Barkley to fall in sections. But merely flooring Barkley wasn’t enough for the rampaging Benn, for the sight of his fallen foe moved him to glare down at Barkley, set his feet, pull his arm back, take aim and strike him with another right to the temple.

“That definitely should be a point deduction,” ABC analyst Alex Wallau yelled in righteous indignation. “He’s been warned already in this round about hitting a man when he’s down and that is grounds, in my opinion, if he landed a harder punch, for disqualification. It’s just outrageous!”

While Padilla issued another warning, he didn’t penalize Benn for the obvious foul and allowed the fight to continue. Barkley’s will may have been as strong as ever but his legs couldn’t match his desire because they couldn’t withstand yet another flush right hand. Barkley fell to the floor but Padilla, unsure whether the fall was the result of a failed clinch or Benn’s blow, briefly consulted with commission members at ringside. One of them crisscrossed his hands, prompting Padilla to do the same.

“I was so within myself, I was so hyped up I just lost everything,” Benn told Wallau. “It’s really hard to tell you how I actually feel when you got someone going. I was so determined to show everybody us Brits ain’t a bunch of pussies. We come to fight.” After seeing the replay of the second knockdown, Benn admitted what he had done, then lodged a challenge at Sugar Ray Leonard, who in recent days had signaled interest in a Hearns rematch.

Meanwhile, Barkley had issues with the way the fight was stopped.

“He never hurt me,” a defiant Barkley stated. “We were throwing our best, he caught me with some shots but it’s bull that they stopped it like that. I’ll take it to a protest but it won’t do any good. I don’t want to sound like sour grapes, if I say a man beat me, a man beat me. But I demand a rematch. If not, no problem. I think if that’s it, I’ll just hang up the gloves.”

Neither man would hang up the gloves for a good long time but their 177 seconds of mayhem will live on as long as explosive middleweight title fights are chosen to be remembered.

Gerald McClellan KO 5 Julian Jackson I – May 8, 1993, Thomas & Mack Center, Las Vegas

Of all the fights on this list, the first encounter between McClellan and Jackson best replicates the dynamics represented by Golovkin-Lemieux. Like Lemieux, the 25-year-old McClellan was the exciting young bomber with an imperfect record looking to prove he belongs with the biggest names in the division as well as with the elite in all weight classes. He won the vacant WBO title with a one-round smashing of John Mugabi 18 months earlier but never defended that belt. Instead he crushed his next four opponents – three in the first round and the other in round two – to raise his record to an imposing 27-2 (25) and extend his knockout string to nine.

As for Jackson, he was the established king of the hill in terms of middleweight punching prowess. Pound-for-pound and punch-for-punch “The Hawk” rates with the best who has ever lived and one only needs to look at his knockouts of Terry Norris, Buster Drayton and Herol Graham to know why. A friendly, gentle and devout man outside the ring, Jackson was a beast inside it as his wrecking-ball punches left dozens of opponents at his feet. His record going into the McClellan contest was an intimidating 46-1 (43) with the only defeat coming against future Hall of Famer Mike McCallum. Since then Jackson had won 17 straight, 16 by knockout, as well as titles at 154 and 160.

Jackson was making the fifth defense of the WBC title but entering the bout with McClellan some thought the 32-year-old U.S. Virgin Islander had shown signs of slippage in his last title fight against Thomas Tate. Tate’s movement and snappy punching made Jackson appear slow and the mortars that had destroyed Dennis Milton in 130 seconds, Ismael Negron in 50 seconds and Ron Collins in five rounds had no tangible effect on Tate. Although Jackson went on to win a fairly comfortable decision, the negative narrative had sunk in. But four months after the Tate bout, Jackson reasserted his puncher’s credentials by taking out journeyman Eddie Hall in four in a non-title go.

Though both men scaled within a pound of each other (Jackson was 159 to McClellan’s 160), inside the ring McClellan was markedly larger, especially around the shoulders. McClellan often took full advantage of the considerable rehydration time granted between the weigh-in and fight time and the result often was a physical mismatch that was only exceeded by the gap in power. With Jackson standing across the ring from him, one had to wonder if even his additional poundage would allow him to exceed “The Hawk’s” punching ability. The world would soon find out.

The battle began swiftly as Jackson met McClellan three-quarters of the way across the ring and winged a left hook that just missed while “The G-Man” circled and looked for openings. He missed with his own hook as well as a right hand that Jackson easily side-stepped. There was no feeling-out process here; both were eager to inflict fight-ending damage as soon as possible. A heavy right to the temple caused Jackson’s knees to dip but as McClellan tried to follow up Jackson nailed him coming in with a tremendous hook that forced him to back off. Within a minute the battle lines had been drawn and they spent the remainder of the fight establishing and re-establishing those lines.

While McClellan won round one, Jackson was determined to make the second his as he jabbed strongly and followed with sweeping power shots. As a result McClellan spent an unusual amount of time on the back foot but even in that posture his punches projected menace. A stiff right from Jackson wobbled McClellan with a little more than a minute remaining and not long afterward he won an exchange of left hooks. Two more huge right hands crashed against McClellan’s jaw in the final 30 seconds, closing out a terrific bounce-back round for the defending champ.

A confident Jackson continued to stalk a somewhat bothered McClellan in the third and the challenger sought to borrow from the champion’s second-round playbook by using his jab to establish his punching range. But Jackson successfully mixed in his meaty right crosses and his concussive left hooks, punches that made McClellan look ragged and unsettled. But then the fight turned when an unintentional butt opened a cut over Jackson’s left eye, an injury that prompted referee Mills Lane to call a time-out and alert the judges. That cut, and the few seconds of extra rest, lit a fuse within McClellan. The challenger rushed in and landed a hook to the jaw that drove Jackson to the ropes and forced him to clinch. As the round closed McClellan’s jab suddenly began to land stiffly and frequently. Though Jackson appeared to win the round, the momentum now was with McClellan.

Jackson tried to rectify that with his first punch of the fourth, a whizzing hook that missed the target. McClellan, though on the move, was doing so smoothly and with assuredness. His jabs were hard, straight and accurate and he radiated a strength and power that had been notably missed just minutes earlier. McClellan easily won the round and looked in good position to capitalize in the fifth.

Jackson attempted to regain command at the start of the fifth as he stepped forward and planted a heavy hook to the body, missed a right to the jaw and blasted another hook to the ribs. McClellan took the blows without much difficulty and was content to slap on clinches and rest. A low hook caused McClellan to fall to his knees, prompting a brief time-out. McClellan used the time to gather himself, after which he sought to gather in Jackson – and his title belt.

That effort was successfully achieved with stunning suddenness. A massive overhand right to the temple caused Jackson’s body to break into a sagging retreat, after which an arcing left hook to the chin sent him flying, then landing spread-eagled under the bottom rope. Jackson somehow got to his feet by six but McClellan, his blood boiling to overflow levels, ran across the ring and floored Jackson a second time with a flush right to the jaw. The champion arose but with his face covered in blood and his body turned away and teetering Lane had seen enough. It was an explosive ending to what had been an explosive contest.

“Julian punched very hard,” McClellan good-naturedly told analyst Dr. Ferdie Pacheco as Jackson stood a couple of feet away. “I got a tremendous headache; I’m going to go back to the room, maybe sleep two or three days. That was a good fight, Julian.”

We agree.

Arthur Abraham W 12 Edison Miranda I – Sept. 23, 2006, Rittal Arena, Hessen, Germany

Abraham may not receive much credit from American fight observers but at middleweight his fists were capable of ending a match with the suddenness of a light switch clicking off, especially with the right hand. He began his career with 14 consecutive knockout victories and entering this, his third defense of the IBF middleweight title, “King Arthur” was in the midst of a power outage as four of his last seven bouts, including his last two, had gone the 12-round distance. Still, his 21-0 record had 17 knockouts and in Germany, he had proven to be difficult to beat.

Colombian Edison Miranda didn’t care where he fought or who was standing in the other corner. In his mind, any gloved man in the ring with him was in danger and the proof could be seen in his record: 26-0 and 23 knockouts, 19 of which were scored in two rounds or less.

Miranda strode down the aisle with murderous intent as he repeatedly flashed the “throat-slash” gesture. Meanwhile, Abraham, a crown adorning his head, sought to radiate the command of a monarch – a middleweight monarch.

The first three rounds saw the volcanic Miranda fire endless streams of power shots while the cerebral Abraham bided his time, picked his shots and only cut loose in the final minute in the hopes of stealing the round on the scorecards.

Many punchers claim to possess bone-breaking power but Miranda proved his was genuine in the fourth when a right uppercut to the tip of Abraham’s opened mouth instantly snapped the champion’s mandible. From that point forward Abraham was unable to close his mouth and dark blood spilled onto his chest and trunks. Miranda’s desire to win the championship combined with Abraham’s dire predicament caused the challenger to fight recklessly – and often illegally.

An intentional butt by Miranda forced a four-and-a-half minute time-out during which referee Randy Neumann, after consulting with commission members, deducted two points from Miranda and gave Abraham the option to continue. At first he was understandably reluctant but accepted the task when he was queried a second time. Abraham preserved his jaw by moving, ducking, clinching and punching only when the openings presented themselves while the wild-eyed Miranda continued his rule-breaking. He lost two more points for low blows in the seventh and a fifth point in the 11th.

With every passing round Abraham’s injury grew more grotesque. His face became misshapen and the mere act of taking out his mouthpiece was a chore for his corner men and pure agony for Abraham. Abraham’s bravery cannot be overstated: He fought eight-and-a-half rounds with a jaw broken in two places against the division’s hardest puncher yet he never hit the canvas. Moreover, he lost approximately a liter of blood.

But Abraham didn’t just survive, he fought back, albeit in spots. His fortitude, combined with Miranda’s multiple point deductions, enabled Abraham to leave the ring a 116-109, 115-109 and 114-109 winner. He then underwent emergency surgery, during which two titanium plates and 22 screws were inserted.

For Abraham, who spent the next three days in intensive care, there were no regrets.

“I know for sure I’ve done the right thing,” he said. “It’s been a question of keeping my world championship belt but it’s been about more. It has been a question of honor and pride. I was leading on points and without the injury I would have knocked out Miranda — definitely. But I never would have given him the belt through concession.”

Abraham’s trainer Ulli Wegner took considerable criticism for what they considered was his callousness. But when asked about Wegner’s actions Abraham took the blame.

“I never would have forgiven my coach for that!” he said. “We’re a team, we know each other quite well — he never would have been allowed to stop the fight. Moreover, I was completely lucid. The referee asked me about 10 times if I wanted to go on and 10 times I said ‘yes.’ In the ring I’m King Arthur Abraham and I never concede. That’s it!”

*

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, W.Va. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 13 writing awards, including 10 in the last five years and two first-place awards since 2011. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. He is the author of “Tales from the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics. To order, please visit Amazon.com or email the author at [email protected] to arrange for autographed copies.