Evander Holyfield living his (first) dream through his son, Elijah

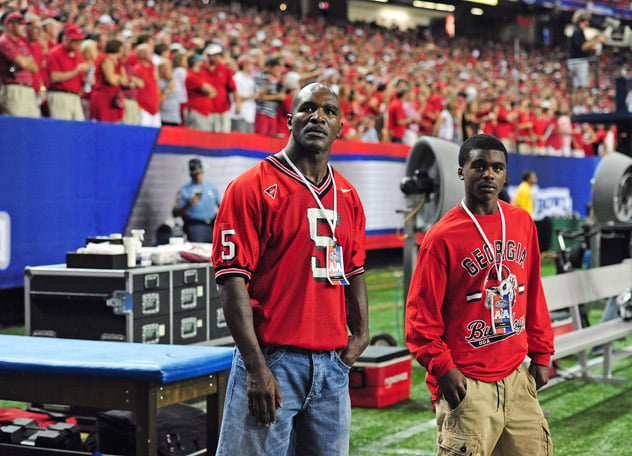

Evander Holyfield on the sidelines with his son, Elijah, in 2011. Photo by Scott Cunningham/Getty Images.

Perhaps it was the disappointment of having to settle for a bronze medal at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, because of his dubious disqualification by a Bulgarian referee in a semifinal bout he seemed certain to win en route to likely gold. Perhaps it was because he still thought he might be able to live an earlier sports dream that he hadn’t entirely given up on.

Whatever his rationale, Evander Holyfield shocked Ken Sanders, who had a deal in place to manage Holyfield’s professional boxing career, when the Atlanta resident returned from the Olympics and revealed he was considering quitting the ring to walk on as a running back for his favorite college football team, the University of Georgia Bulldogs. It was a bold and probably foolish notion on the part of Holyfield, who had stopped playing football in his sophomore year of high school because of a lack of playing time and the coaching staff’s conclusion that he was just too small and unremarkable to ever amount to much on the gridiron.

Sanders convinced the 21-year-old Holyfield, who by then had filled out to 6-foot-2¾ and 190 or so pounds, to stick with boxing, which clearly was the proper call when you consider that Evander went on to become the undisputed cruiserweight champion before moving up to heavyweight, where he won at least a version of the title an unprecedented four times and was shafted out of a fifth belt on a ridiculous majority-decision loss against 7-foot, 310¾-pound WBA champ Nikolay Valuev on Dec. 20, 2008, in Zurich, Switzerland. During his 27 years as a pro, Holyfield, a mortal lock to be inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2017, his first year of eligibility, earned in excess of $200 million in purses and the admiration of fight fans around the world.

Asked now if he could go back in time and have the choice of being the undisputed heavyweight champion of the world or the NFL’s greatest running back, Holyfield finally allowed that, yes, he’d rather travel the path he once was hesitant to take.

“No doubt, heavyweight champion of the world,” Holyfield responded. “Anywhere you go, in any country, if you’re the heavyweight champion, people know who you are.”

Still, Holyfield speaks wistfully of his hero-worship of the Atlanta Falcons’ Dave Hampton, a player on the fringes of stardom who in 1975 became the first running back in franchise history to rush for 1,000 yards in a season when he finished with 1,002 yards. Hampton had just missed out on quadruple figures in 1972 and ’73, when he rushed for 995 and 997, respectively.

“Being from Atlanta, I loved all the home teams,” said Holyfield, now 52. “That includes the Georgia Bulldogs. Wasn’t nothing I wanted more than to play for that team. Herschel Walker had won the Heisman Trophy for Georgia (in 1982). It was my dream to be another Herschel Walker, and then to play for the Falcons and be another Dave Hampton.”

Photo: Atlanta Journal-Constitution

It is a dream that still might come true for Holyfield, one generation removed. Elijah Holyfield, the eighth of Evander’s 11 children by several women, is a consensus four-star running back at Woodward Academy in College Park, Georgia, who has enjoyed the sort of prep-football success that evaded his father, and the heavily recruited 5-foot-11, 205-pounder will announce his college choice on Sept. 4. Georgia is among his five finalists, along with Auburn, Alabama, Tennessee and South Carolina.

“I feel like I’m an SEC (Southeastern Conference) back,” said Elijah, who previously had considered Michigan, Notre Dame, Southern California, Ohio State, Louisville and Georgia Tech, among others. “The best backs in the nation play in the SEC. They have the best chance of going on to the next level (the NFL). In the SEC, you get to play with and against the best competition.”

Wherever Elijah, who lives with his mother and stepfather, winds up, it’s a safe bet that his father will be in the stands, cheering him on and vicariously seeing this younger version of himself do the sort of things on the field he never had an opportunity to do himself.

Elijah already was on many big-time colleges’ radar going into the 2014 season, but his performance in Woodward Academy’s first game against Decatur served to drive his “wow” factor even higher. Not only did he return the opening kickoff 84 yards for a touchdown, but he followed that up with six more TDs, all on rushes, in a 45-13 rout.

“It was just one of those games when you’re, like, really hot,” said Elijah, shrugging off those seven scores as if it were an everyday occurrence. “The only bad thing about it is after you do something like that, you have to live up to it the rest of the year.”

Elijah more or less did just that, scoring 25 touchdowns in leading the War Eagles – might that be a good omen for Auburn? – to an 11-3 record and berth in the Georgia Class AAAA semifinals. Mike Farrell, a recruiting analyst for Scouts.com, said Elijah – rated by his service as the 128th best high school player in the country, and fifth-best running back – is good enough to stand on his own, without any embellishment from his father’s celebrity status.

“He deserves the attention,” Farrell said. “I think early on, because of his last name and because his dad is such a famous figure, Elijah got a little bit more of a look. But he would be getting the offers he’s gotten regardless. He’s a really good running back.

“Elijah runs a little bit upright, which means he doesn’t always have the best leverage, but it really doesn’t matter because he has tremendous instincts and good vision. He’s a power runner who is tough between the tackles, but has a good jump-cut and can take it outside and make people miss.”

There is no possibility, of course, of Elijah being just one of the guys on the team; everyone knows who his father is, and he understands that every time he does something exceptional – and whenever he doesn’t, for that matter – he’s going to be compared to Evander. Hey, didn’t baseball’s Ken Griffey Jr. come to expect being gauged against his dad, Ken Sr., an outfielder with the Cincinnati Reds’ “Big Red Machine” dynasty of the 1970s? And what about Archie Manning’s Super Bowl-winning quarterback sons, Peyton and Eli, whose formative years were spent in the long shadow of their pop?

“I would say it’s more of a blessing than a drawback,” Elijah said of the last name that has always set him apart. “I can’t control who my dad is. I try not to make too much of a big deal about it, but it does add a little bit of pressure. More people are always going to be looking at you.

“I hear people say, ‘Oh, he’s not as good as everybody says he is, he just gets attention because of his name,’ or whatever. But, really, pressure doesn’t bother me. It makes me work even harder. If somebody wants to think I’m privileged in some kind of way, or thinks I don’t want or have to work hard because of who my dad is, that’s their problem. I’m Elijah Jedediah Holyfield. Yeah, I’m Evander’s son, but I’m also my own person.”

Elijah – whose favorite running back, in case you’re interested, is former San Diego Chargers great LaDainian Tomlinson – doesn’t need to have his ego toned down much more. Evander was never a chest-thumper, and his sense of humility, as well as his work ethic, seems to have been passed along to Elijah.

“You can always improve,” Elijah said. “I continue to work on my speed, my cuts, stuff like that. When I was growing up I played football, baseball, basketball. I wrestled, I boxed for a while, I ran track all my life. I tried to take something away from all of it and use it to make myself better.”

So what did the younger Holyfield learn from boxing?

“Boxers, the good ones, have to work really hard,” he allowed. “If a boxer trained harder than me, I was determined to train as hard as he did in my offseason workouts. And you know what? I can see the results.”

Evander never got a chance to score all the touchdowns that Elijah does, but he said it couldn’t happen without the offensive linemen who open the holes that his son gets to run through.

“Elijah liked to box when he was younger,” Evander recalled. “But I could tell his first love was football. Really, it was mine as well. The only reason I didn’t stick with it was because I didn’t like sitting on the bench all the time. My mama told me to stop all that complaining. She told me I shouldn’t quit, to stay with it until the coaches put me in and saw what a good player I was. I didn’t listen to her. I was too proud to sit on nobody’s bench.

“One thing led to another and I finally decided to concentrate on boxing. Mama said, ‘Son, if you don’t want to play football, box. Put your all into it. But whatever it is, put your all into something.’

“Look, life is not about cloning your kids and making them do what you do. You want to tell your kids to find something they love and to give their all to it. But whatever that is, they got to do it for themselves and not for anybody else.”

Photos: Atlanta Journal-Constitution (L), Andrew D. Bernstein/Getty Images (R)

Maybe the person most capable of understanding Elijah’s situation is Ken Norton Jr., son of the late former WBC heavyweight champion Ken Norton. The elder Norton is best known for breaking Muhammad Ali’s jaw in the first of their three meetings, and for going to hell and back in losing his title on a 15-round split decision to Larry Holmes in what became an instant classic. But Norton didn’t want his athletically gifted sons, Ken Jr. and Keith, to box, and he even forbade them to watch his fights on television.

Ken Jr. went on to star as a linebacker at UCLA and then for 13 seasons in the NFL, winning four Super Bowls – three as a player (two with the San Francisco 49ers, one with the Dallas Cowboys) and one as an assistant coach (with the Seattle Seahawks). Now the first-year defensive coordinator with the Oakland Raiders, Norton Jr., although he never boxed, paid homage to his dad by tossing air combinations whenever he made a good play, and, as a coach, by talking to his players as a wise trainer might to his fighter.

“(Boxing) is part of what I do,” Norton Jr. once said. “No matter what, I can’t get away from boxing. I guess that’s because of my dad. He was always my Superman. He showed me how to be a man, always was there for me as a father, showed me that I can be successful with hard work and dedication. He was very demanding of me, making sure that I grew up with a certain amount of respect and dignity, understanding that the Norton name means an awful lot.

“The older I got, I really began to appreciate his sacrifice, his triumph, his struggle, what he was able to accomplish at the same time being a father. It made me want to make him proud. Made me want to do something to make him happy, where he could say, ‘That’s my son.'”

Elijah said he would have a chat with Norton Jr. one day, if only to compare notes. He suspects that their similarities far outnumber any differences.

“I’m pretty sure,” Elijah said, “he went through some of the things I’m going through now.”

Evander said the key to achieving real balance in life is to have confidence in yourself, but not so much that your forget that everyone needs help now and then.

“My mama always told me I had to stay humble, and that’s what I tell Elijah,” Evander said. “When I was a kid, I wasn’t confident. I wasn’t popular. All that started to change because of my attitude. You don’t need to brag. If other people talk good about you, fine. But don’t keep talking about yourself. Being overly proud is a trap that’s easy to fall into.

“When Elijah scored all those touchdowns in that game, I told him to make sure to give credit for the players blocking for him. I told him to get it out of his head that he was doing it all by himself.”

It’s no surprise then that after one of Woodward Academy’s games last season, a beefy offensive lineman came up to Evander to shake his hand. But it wasn’t the hand of a former heavyweight champion that the large young man sought to clasp; it was the hand of Elijah’s dad.

“Mr. Holyfield,” Elijah’s teammate said, “I just wanted to tell you how much I enjoy blocking for your son.”