Head-to-head for pound-for-pound: Whitaker-Chavez remembered

When Floyd Mayweather Jr. and Manny Pacquiao answer the bell Saturday night at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas, they will begin the drive toward their ultimate destiny. Barring a draw or some other unforeseen controversy, the winner will be able to claim superiority not just over the other man but also over the era in which they fought.

While THE RING’s welterweight championship (and three sanctioning body belts) will be at stake, Mayweather and Pacquiao also will compete for something more: The mythical, pound-for-pound championship. Ever since THE RING began running P4P rankings in its Jan. 1990 issue, there have been only nine head-to-head meetings between fighters in the top five. Mayweather-Pacquiao, the 10th, will be just the second encounter between a No. 1 (Mayweather) and a No. 3 (Pacquiao), with the other being Felix Trinidad (No. 3) controversially outpointing Oscar De La Hoya (No. 1) in Sept. 1999.

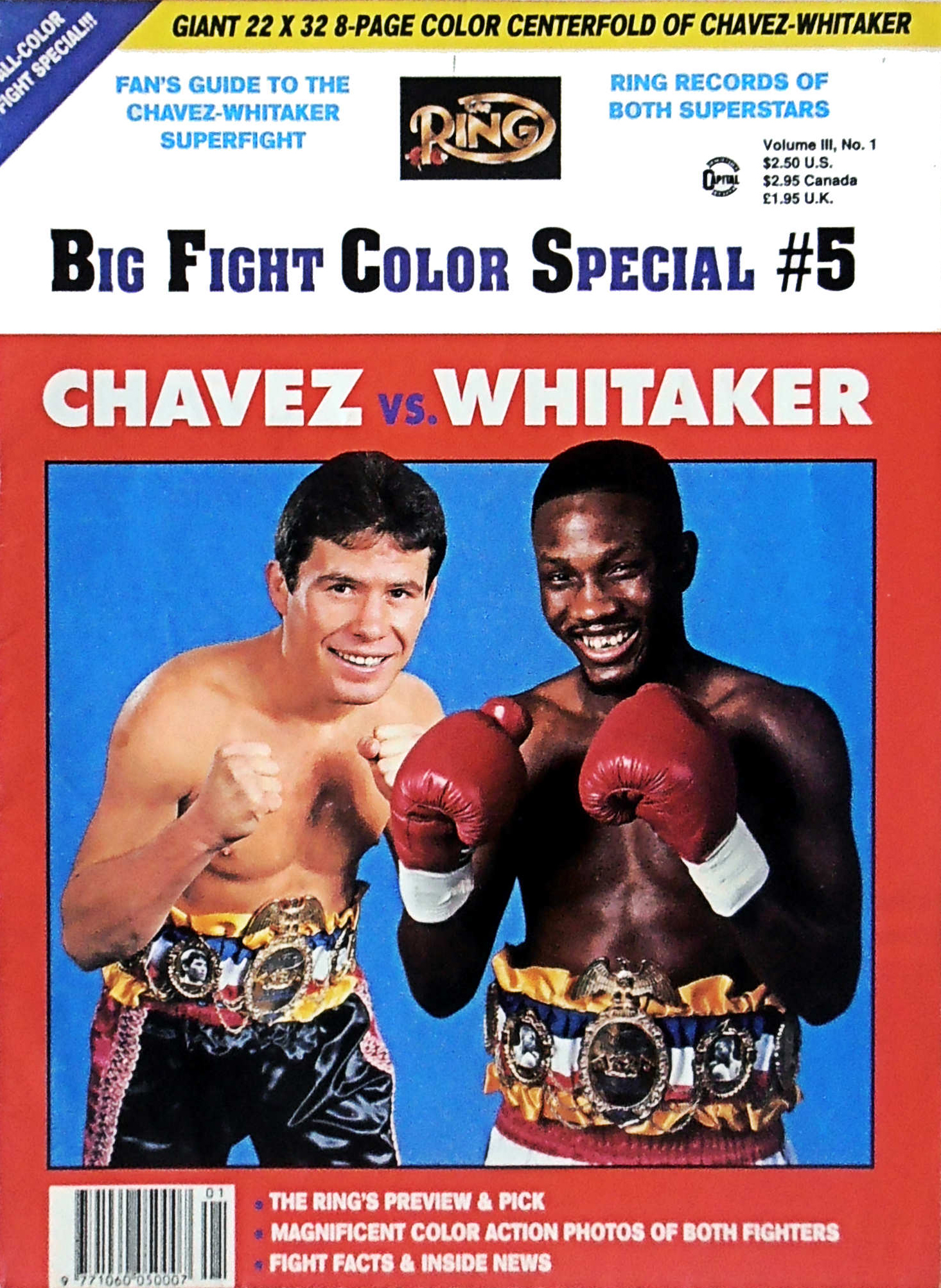

But there has been just one fight in THE RING’s pound-for-pound era that has pitted the top two fighters on the list: No. 1 Julio Cesar Chavez vs. No. 2 Pernell Whitaker. Their Sept. 10, 1993 clash inside San Antonio’s Alamodome shares several parallels with Saturday’s match in terms of contrasting styles, divergent personalities and politically-driven, logistical difficulties.

Like Mayweather, Whitaker was his era’s most dexterous defensive wizard. His southpaw stance and array of dips, slips and counters left opponents baffled, frustrated and ultimately outclassed. Not only did Whitaker win fights, he did so with extraordinary mathematical domination. In back-to-back lightweight title defenses against Anthony Jones and Poli Diaz, Whitaker won 71 of a possible 72 rounds on the judges’ scorecards and he achieved similar whitewashes against John Montes, Alfredo Layne, Greg Haugen, Jose Luis Ramirez (on two cards in their rematch) and Harold Brazier. The similarities to Mayweather didn’t end inside the ring, for Whitaker’s supreme confidence struck some as arrogant and abrasive. Whitaker may not have had Mayweather’s mansion or his fleet of high-performance cars but the man known as “Sweet Pea” (a mishearing of his actual nickname, “Sweet Pete”) was every bit as sublime inside the squared circle.

On the surface, Pacquiao and Chavez are opposites in that the Filipino is a southpaw, has far nimbler footwork and fights more frenetically than the well-grounded, right-handed Chavez. But their core ring philosophies were similar as both thrived on relentless aggression and precise combination punching. They also had to fight through facial cuts – Pacquiao has repeatedly suffered gashes over the eyes while Chavez had to cope with a nagging slice across the bridge of his nose. In terms of temperament, they tended to be on the quieter side in public but they exuded an intense and profound pride. Finally, every time Pacquiao and Chavez entered a boxing ring, they carried the weight of an entire nation. Chavez is widely considered to be the very best fighter boxing-rich Mexico has ever produced while Pacquiao has the same honor for the Philippines and both carried out their ambassadorial duties with aplomb.

As is the case with Mayweather-Pacquiao, Whitaker-Chavez was a difficult fight to put together because of the high-risk nature of the match-up to each man’s reputation as well as their promotional and pay-cable alliances. Whitaker, promoted by Main Events, had a longstanding relationship with HBO while Chavez’s recent fights had aired on Showtime, mostly because of his affiliation with promoter Don King. Unlike Saturday’s match, Whitaker-Chavez did not have any multi-network pollination in terms of production or on-air talent; it was a Showtime-run endeavor all the way as the live broadcast was beamed under the SET (Showtime Entertainment Television) banner and was called by blow-by-blow man Steve Albert and analysts Bobby Czyz and Dr. Ferdie Pacheco.

The political strain continued through the rules meeting, in which a dispute over the judges briefly threatened to derail the fight. Chavez and his team was angered that an American judge was on the panel (Texas’ Jack Woodruff) without a Mexican counterpart and, absent the insertion of a Chavez countryman, they said they would refuse to fight unless all three jurists were from neutral nations. Whitaker and his team, headed by promoter Dan Duva, said they would pull out if any changes were made. None were and the crisis was averted. While Whitaker’s team prevailed on the make-up of the judging panel, Team Chavez was able to secure one important concession from the champion’s camp – a catchweight of 145.

This was a fight that was awash with historical significance. At 87-0 (75 knockouts), Chavez had assembled the longest winning streak from the beginning of a career in the modern era, the sixth longest win streak at any point of a career, and his 25-0 (18) record in championship fights was the longest such run in ring annals. If he defeated Whitaker, Chavez would become only the fourth fighter ever to capture major belts in four weight classes. The other three: Sugar Ray Leonard, Thomas Hearns and Roberto Duran.

Like Chavez, Whitaker (32-1, 15 KOs) was a three-division champion who had defeated every man he had faced as a pro, for he avenged his only loss – a hotly disputed split decision to Ramirez in March 1988 – with a decisive points win 17 months later in a two-belt unification match. Whitaker then added the WBA strap by starching Juan Nazario in one round. For good measure, he defended the unified championship three times before moving up to 140 pounds and capturing Rafael Pineda’s IBF title. In all, Whitaker was 11-1 in championship fights but with only three stoppage wins.

Both were coming off impressive victories. Six months earlier, Whitaker captured the WBC welterweight title from James “Buddy” McGirt before McGirt’s home fans at Madison Square Garden while Chavez scored a scintillating sixth-round TKO over universal mandatory challenger Terrence Alli two months later. At the weigh-in, both appeared in supreme shape as Whitaker scaled 145 and Chavez a ready 142.

“This fight is for the title of best pound-for-pound fighter in the world,” Whitaker said in an Associated Press story. “That is the title every man dreams of. This fight is the World Series, Super Bowl, NBA Finals. It’s boxing’s two best fighters.” And unlike Mayweather-Pacquiao, whose high-definition broadcast will sell for $99.99, buyers back in 1993 could see the four-fight pay-per-view (of which three were title bouts) for just $29.99.

For the first time in more than four years – when Chavez defeated Mayweather’s uncle, Roger, for the WBC super lightweight title – “El Gran Campeon Mexicano” was thrust into the role of challenger. It was a role he relished.

“Now that I’m a challenger, I’m a lot hungrier than I have been,” Chavez told the AP through interpreter Gladys Rosas. “I’m going to demonstrate how a challenger should fight a champion when he wants to win a title.”

“Everybody thinks this will be the toughest fight of my life,” Whitaker countered. “It will be the easiest fight.”

Nearly 60,000 souls (59,995, to be exact) entered the Alamodome to witness the spectacle, falling short of the indoor record held by the Muhammad Ali-Leon Spinks rematch in New Orleans nearly 15 years earlier (63,350). The vast majority of the 75,000-seat stadium was packed with passionate Chavez fans who roared with near-religious fervor as their man walked toward the ring to the accompaniment of a live mariachi band. The cheers turned to robust boos as Whitaker entered the arena to the strains of Naughty by Nature’s “Hip Hop Hooray.”

The odds in Chavez’s favor swung wildly, as one source quoted nine-to-five while another cited two-to-one. A rush of late money on the Mexican pushed the line at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas to three-to-one. Expert observers, however, knew the mesh of styles and talents would result in a tough, close and hard-to-score match.

“These are two guys who, for their entire careers, have made their opponents fight their fights,” Emanuel Steward said before the fight. “Something’s gotta give.”

What gave early was Whitaker’s ability to stand his ground. Chavez, painfully aware of his slow-starting ways, promised to come out of the gate much faster and, this time, he more than lived up to his vow. Fighting with an unusual amount of urgency, Chavez drove forward behind rights to the body designed to drain Whitaker’s legs while the champion fired darting jabs and one-twos while executing almost constant pivots. Whitaker tried to shake Chavez’s concentration with one of his patented deep knee squats but Chavez, ever focused, simply waited for Whitaker to rise before resuming his charge. At the bell, the fans unleashed a roar, convinced that Chavez had earned the early lead.

Chavez opened the second by landing a lead right to the face and, after tasting a spearing left from Whitaker, threw several punches in the clinches, a move that drew a caution from referee Joe Cortez. Chavez’s lead rights hit the target with startling regularity while Whitaker’s offerings, while landing, lacked the power to discourage the challenger. Whitaker fared well during a mid-round exchange of body punches but the fact that he was drawn into such a situation was evidence that Chavez, at least early on, was dictating the flow. Whitaker, his frustration growing, popped Chavez with a low blow and a mushing right to the face during the break. Another punch on the break nearly moved Cortez to deduct a point but he opted to refrain. When the bell sounded, Chavez had swept his second straight round on the scorecards.

At this point, it was clear that Whitaker needed to up his game lest he be run out of the ring. A slow, comfortable boxing match was out of the question, especially in his highly-charged atmosphere, so it was Whitaker’s mission to find a way to impose his science. The building blocks of his strategic shift began taking shape at the start of round three, when he met the onrushing Chavez with several stiff jabs to the face, after which he pivoted, reset and repeated the process time and again. In less than a minute’s time, Chavez’s hyper-aggressiveness slowed perceptively, which gave Whitaker the necessary breathing room to execute his blueprint. In fact, Chavez even began to give ground and, at that point, Whitaker snapped two hard jabs to the face and spun away. Soon Whitaker mixed in chopping lefts to the face and multi-punch bursts that kept Chavez overly occupied on blocking the incoming. An excellent right hook to the head jolted Chavez’s head and a left cross to the face at the bell punctuated an excellent three minutes for the champion. That said, Whitaker had to work very hard to keep Chavez away from him and the big question was whether he had the stamina to keep it up for the entire 12 rounds.

It didn’t look that way as the pair engaged in intense, draining and occasionally dirty infighting to start the fourth. Both men were warned about low blows and there was plenty of punching in the clinches, developments that surely favored the more physical Chavez. Whitaker felt he wasn’t getting any help from Cortez and he showed his frustration by slapping away the referee’s hand as he separated the fighters. Cortez took umbrage at Whitaker’s disrespect and when Whitaker placed both gloves on the sides of the official’s head in apology, Cortez pushed Whitaker’s arms away and firmly ordered, “Don’t be pushing me.” Chavez whacked Whitaker on the thigh as the champion sprung up from another deep squat, which also prompted words from Cortez. After that skirmish Chavez, strangely, began boxing on the back foot while Whitaker stalked, a role-reversal no one could have anticipated. The switch worked to Whitaker’s advantage as he stuck Chavez with straight, scoring blows. Though the fighters reverted to their usual fighting modes a few moments later, Whitaker continued to control the action with his strafing punches. Now it was Chavez’s turn to be frustrated as he shoved a glove in Whitaker’s face just before the bell, a bell that signified that Whitaker had just evened the fight.

“Now you’re boxing; now you’re boxing out there,” co-trainer Lou Duva happily exclaimed. “That’s what you have to do; that’s all.”

“Continue to do what you’re doing,” added George Benton, a former middleweight contender who was considered an excellent ring general in his day. “Don’t give him nothing. Keep that circle going for you. Keep that right jab working. When you get on the inside, I want to see them uppercuts working. You’re doing a hell of a job. The jab is the one that’s going to keep him in check. When you ain’t doing nothing else, I want you to jab.”

Stung by Whitaker’s rally in the third and fourth, Chavez roared out of the gate in the fifth and wailed away at the champion’s flanks with both hands. But Whitaker weathered the storm, then struck Chavez with a spearing right. The action continued to ebb and flow throughout the session but even though Whitaker looked to have the edge, all three judges awarded the round to Chavez – the last round he would sweep.

In a night filled with action and controversy (the Azumah Nelson-Jesse James Leija draw drew much criticism), one of the more defining points of debate occurred midway through the sixth when Whitaker cracked Chavez with a low blow that caused the Mexican to grimace and turn away in pain. Though Cortez gave Chavez time to recover, he would have been within his rights to deduct a point from Whitaker, especially since it wasn’t the champion’s first offense – or his second…or his third. But Cortez kept his powder dry and simply issued a subdued caution. Moments after the action resumed, Whitaker cranked another blow to the hip but, once again, the champion escaped the point deduction. Two flush jabs to the face by Whitaker brought the curtain down to a most tumultuous round.

With emotions boiling over, the seventh was even more intense than the foul-filled sixth. Chavez charged in recklessly and fired punches from all angles while Whitaker shifted angles and delivered up-and-down bursts that sliced through the guard with full-shouldered strength. A blurring right-left snapped Chavez’s head in the final minute and his follow-up left crosses set up by range-finding jabs won him the fiercely contested stanza.

The hot pace continued throughout the eighth as Chavez charged and Whitaker countered, each doing so effectively. But Whitaker’s cleaner and more easily-seen punches enabled him to create some much-needed separation, both geographically and on the scorecards. The heavily pro-Chavez crowd, so boisterous before the bout, now buzzed anxiously because they sensed their hero, if he were to win, would have to conjure the kind of stretch drive that saved his bacon against Meldrick Taylor. A massive Whitaker left to the jaw in the round’s final minute only drove home that point. Suddenly, Chavez looked every bit like a 31-year-old man with 87 pro fights on his odometer while his 29-year-old tormentor had the look of a man in command of his craft and conditioning. Although the fight remained close in terms of points, it was evident that a new narrative was being written.

“Give me the same round,” Benton told Whitaker. “Keep turning him and keep giving him them combinations. Now you made a hell of a stand.”

Chavez tried to regain the momentum early in the ninth by rushing at Whitaker but now the champion had all the right answers at his disposal. He retreated just enough to maintain his preferred range and punched more than enough to tell everyone he was boxing, not running. Chavez landed several snappy rights in the session but Whitaker was quick enough with his response to neutralize any edge Chavez might have created for himself. Still, the ninth was a better round for Chavez and, in the corner, his seconds tried to lift his spirits for what they hoped would be an inspired final nine minutes.

“That’s the kind of round we need,” Chavez’s corner said through Pacheco. “You can’t stop fighting and let this guy get off. The guy is tired now and – come on – we’re going to win this. He’s dead. He’s dead. He’s shot his bolt. You took that one; give us this one.”

Chavez took their words to heart and did his best to translate them into action as he chugged ahead and fired power shots from multiple angles. Whitaker, however, was a human protractor as he popped Chavez with singular body shots and crisp counters that ripped through the guard. Yet another low blow found Chavez’s protective cup but since a few rounds had passed between violations, Whitaker was given a brief caution before the action resumed. But even if a point had been docked, it would have been, at worst, an even round. Chavez’s punch output plummeted while Whitaker’s ring generalship shined. Chavez’s corner may have been yelling, “You first! You first!” but in the 10th, Whitaker was first, second, third and fourth.

Ever mindful of the judging situation, Duva and Benton urged Whitaker to not rest on his laurels.

“Don’t let the guy steal these two rounds,” Benton said. “I don’t give a damn what happened. Don’t let this guy steal these two rounds. Just keep your hands moving; keep your jab going and, when you get close, move your hands.”

The same message was being delivered to Chavez.

“Don’t let this guy win these last two rounds,” Chavez was told. “You’ve got to go all out. We need these two rounds.”

Both men answered the bell physically, then proverbially as they invested full energy into their attacks. As always, Chavez plowed inside with fists pumping but Whitaker’s blows were more precise and jolting. Whitaker appeared the fresher man as Chavez leaned against the ropes, against Whitaker and even against Cortez at one point. A needle-sharp left followed by a left uppercut nailed Chavez with 18 seconds remaining, igniting a final burst by the Mexican icon that mostly found air. Therein was the difference between the pair at this late stage.

“Well, that’s another one in the bank for Whitaker and it’s starting to look like the end of a long trail for Chavez,” Pacheco declared near the end of the 11th.

By now the crowd was nearly silent, for most couldn’t believe what they were seeing. For more than 13 years, Chavez’s fans had known nothing but perfection. The Taylor fight gave them a mighty scare but even that story had a glorious ending thanks to the imperceptible but undeniable punishment Chavez dished out during the middle rounds. But here, Chavez was unable to break Whitaker’s body or his spirit and, entering the final round, it was he, not the champion, who was the wearier man.

In the corner, Chavez was being given a final verbal push and even one of his sons – seven-year-old Julio Jr. – joined in the chorus.

“Hit him, Daddy,” he said. “Hit him!”

A victory here would have qualified as an even bigger sporting miracle than the Taylor finish because Whitaker was stronger, fresher – and smarter. After the Taylor fight, Chavez called the ending “a gift from God,” but as Czyz would say during the final round that even God can only be so generous to one man.

Whitaker spent the early part of the round not running around but charging inside, bulling Chavez to the ropes and fighting just enough to keep Cortez from separating them. As the round swung into the second minute, Whitaker mustered a brief surge along the ropes, then smoothly spun away to his right and reestablished his long-range game. In the final minute, Chavez – and his crowd – revved up one final burst but Whitaker spoiled their hoped-for party with wizardry and wiles. A split-second before the final bell ,Whitaker landed one last left to the jaw, the final blow to what had been a tremendously dramatic and unexpectedly action-packed encounter.

Both men threw their arms skyward and Whitaker, sure he had just secured a career-defining triumph, climbed the ropes and celebrated while being showered with boos.

Most believed Whitaker had done enough to secure the pound-for-pound title for himself. The punch stats – compiled by CompuBox for United Press International – showed Whitaker outlanded Chavez 311-220 but the distribution of connects may lend credence to what was about to unfold. While Whitaker led 130-38 in landed jabs, Chavez earned a 182-181 edge in connected power punches.

As Whitaker sat in the corner, head between his knees in exhaustion, someone in his corner told him something that made him snap out of his temporary fog and look up in disbelief.

“What?” he asked, shock creasing his face. “I know they didn’t rob me.”

Not long after that scene in the corner, ring announcer Jimmy Lennon Jr. announced to the rest of the world the news that had so aggrieved Whitaker. Woodruff, the judge who had drawn the ire of Chavez’s camp – voted 115-113 for Whitaker. But he was overruled by England’s Mickey Vann and Switzerland’s Franz Marti, both of whom scored the fight 115-115 – a draw. Yes, Whitaker kept his championship but he was denied the historic significance of officially inflicting the first loss of Chavez’s career.

Of all the verdicts that could have been rendered in this super-fight, a draw was the least likely. The few people happy about the decision were those bettors who took a 20-to-1 flyer at the sports books but, for everyone else, it ignited a firestorm of controversy.

The cover of the Jan. 1994 issue of KO captured the sentiment of most observers: “Whitaker Shafted! Outrage at the Alamodome: Only the Judges Were Quick to the Draw.”

Even worse, this verdict could have been avoided. Vann revealed during an interview with the Star of London newspaper that, “I deducted a point from Whitaker for an appallingly low blow in the sixth round.” A judge doesn’t have the power to unilaterally subtract points and his action had a direct bearing on the final result, for Whitaker would have walked out of the ring with a majority decision victory.

Incredibly, Chavez, the perceived loser, swept three rounds on the scorecards (the first, second and fifth) while Whitaker, the presumed winner, did so in two rounds (seven and eight).

A distraught Whitaker refused to give a post-fight interview in the ring but several minutes later, he offered comments to SET roving reporter Montel Williams.

“That’s why I’m glad we got TV and we got millions of viewers watching this one so the public can really decide it,” he said. “It’s a win for me because the public gets to decide it. You take a poll on your next show and you’ll see the ones who say he won and the ones who say who lost. I’m just going to enjoy this one because the people know who the winner is. I feel like Evander [Holyfield] did in the Olympics. This was an Olympics victory for us. I feel like Evander did getting ripped off for the gold, like I got ripped off for this gold. But we’ll come back. We’ll get it back.”

“I’m not satisfied [with the decision],” Chavez said through Gladys Rosas. “Whitaker is a very difficult fighter. It wasn’t one of my greatest nights. I tried my best to force the fight and I believe I won the fight. He surprised me several times but he was doing a lot of things. He was hitting me with low blows occasionally and very intentionally. Whitaker didn’t present a very strong fight to me and I want a rematch.”

So did promoter Don King, who made a possible rematch the main theme of his remarks at the post-fight press conference. Team Whitaker was amenable – but with conditions.

“If there is a rematch, it will be on our terms, what we want,” said adviser Shelley Finkel. “This time, Pernell said, “Don’t make the negotiations hard; make the fight.'”

Of course, there would be no rematch. Three fights later, Chavez officially lost the zero in the loss column as Frankie Randall scored a stirring split decision and when he officially retired 11 1/2 years later, his record read 107-6-2 (86). As for Whitaker, he took over the top spot in THE RING’s pound-for-pound ratings, where he would stay until May 1996 when Roy Jones Jr. assumed the throne. Since then, the pound-for-pound title has been worn by De La Hoya, Jones Jr. (again), Shane Mosley, Bernard Hopkins, Mayweather, Pacquiao and now, again, Mayweather.

For the first time since that fateful night 21 1/2 years ago, a single fight could directly produce an instantaneous shift at the top of the pound-for-pound standings. Although Whitaker-Chavez was declared a draw by two judges, media and fans alike rewarded “Sweet Pete” by lifting him to the number-one spot in the pound-for-pound ratings and should Pacquiao beat Mayweather in inarguable fashion, he likely will leap-frog Wladimir Klitschko into the top spot, making him the third man ever to regain the P4P throne after having lost it. Conversely, if Mayweather wins, he will extend what has already been a remarkable run at the pinnacle of his chosen sport.

History will be made on Saturday but it’s up to Mayweather and Pacquiao to create what kind of history it will be.

*

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, W.Va. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 13 writing awards, including 10 in the last five years and two first-place awards since 2011. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. He is the author of “Tales from the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics.” To order, please visit Amazon.com or email the author at [email protected] to arrange for autographed copies.