From THE RING Magazine: Manny Pacquiao: Substance behind the stare

Manny Pacquiao is tougher than you might think. Photo by Chris Hyde / Getty Images

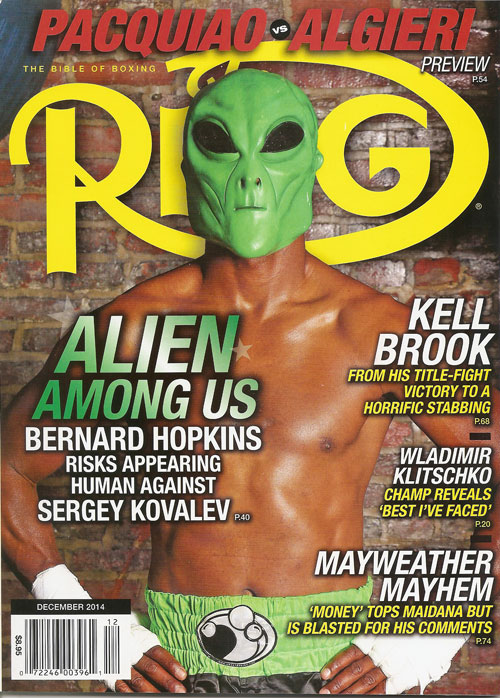

This story is part of the Manny Pacquiao vs. Chris Algieri preview package in the December 2014 issue of THE RING Magazine, which is on sale now. Just click on the link above to purchase the magazine. Or buy it on a newsstand near you. Don’t know where to find a newsstand near you that sells THE RING? Click here. To subscribe ÔÇö both to the print and digital versions ÔÇö click here. You can also purchase the current issue on that page.

His face is a blank sheet, an empty vessel. You pour in whatever you like, you see what you want to see. By minimizing his words and withholding his emotion, Manny Pacquiao is perhaps the least-transparent famous face in sports. Anything you think about the eight-time world champion could be right, or wrong. What’s undisputed is his quickness, his power and his astonishing record.

A career that began with a four-round fight in early 1995, when Pacquiao weighed 98 pounds, has stretched through 20 years, 11 weight divisions and 66 fights. The 67th will happen Nov. 22 in Macau, against undefeated Chris Algieri.

You only do that with qualities that most boxers proclaim they have in abundance – toughness, character, heart. He rarely says a word about any of those, but they might be his most underrated traits.

“He’s had a lot of tough fights,” said Freddie Roach, Pacquiao’s Hall of Fame trainer. “He fought (Antonio) Margarito and took a couple of tough shots. He sort of cringed and I thought he might go down, and he didn’t.”

No, he didn’t. He also turned Margarito’s face into a bloody mess on the way to a one-sided decision that night in 2010.

On the journey to 147-pound dominance, Pacquiao has met and defeated almost every credentialed opponent except Floyd Mayweather Jr. He took on Erik Morales three times, 25 rounds in all, and won twice. He won a decision over Marco Antonio Barrera. Obviously he went through the four-act passion play with Juan Manuel Marquez.

On the journey to 147-pound dominance, Pacquiao has met and defeated almost every credentialed opponent except Floyd Mayweather Jr. He took on Erik Morales three times, 25 rounds in all, and won twice. He won a decision over Marco Antonio Barrera. Obviously he went through the four-act passion play with Juan Manuel Marquez.

And in 2008 he was brazen enough to jump from lightweight to welterweight to challenge Oscar De La Hoya, a weight-defying gesture that most of the boxing world did not quite believe.

“Even some of my fans were worried about that fight,” Pacquiao said.

He retired De La Hoya that night, when the Golden Boy did not come out for the ninth round. Roach, who had trained De La Hoya in his close loss to Mayweather the year before, noticed during sparring sessions that left-handers were a problem. Now in a different corner, Roach bet on Pacquiao’s superior quickness. “He hit Oscar with a shot in the first round,” Roach said, “and I saw the expression on Oscar’s face. And I said, ‘That’s it, he’s done.”’

But Roach knows where the fortitude really comes from. He finds IT in a place he visits before almost all of Pacquiao’s fights.

“It has to do with his upbringing,” Roach said.

***

There are 100 million people in the Phillippines, the 12th most populous country in the world. More than a quarter of those people fell below the nation’s poverty line in 2012. Children are everywhere, unsupervised, some of them homeless, some of them forced into entrepreneurship far earlier than they should be.

When Roach is there with Pacquiao, the champ will often point out a waifish child on the sidewalk. “That was me,” he will say.

“He showed me where he used to sell donuts on the street corner,” Roach said. “He couldn’t look forward to the next day. He had to worry about that particular day. That’s sad, sometimes.”

Pacquiao’s mother and father separated and she wasn’t able to support the six children. At 14 Pacquiao took to the streets. He sometimes slept in a park, underneath a cardboard box. Eventually he made his way into a boxing gym. Fighting as an amateur, he worked a construction job to make it all work.

“Sometimes I was on a high-rise, sometimes on the ground,” Pacquiao said in early September, riding in a van with his friends and his manager, Michael Koncz, as they rode from interview to interview in Los Angeles. Afterward, Pacquiao threw out the first pitch before a game between the Dodgers and Washington Nationals.

“I was welding, I was painting, hammering. I’d make 1,000 pesos a week. That’s $23. That’s how I survived. But it was hard for me to do that and still maintain boxing.”

Pacquiao was a distinguished amateur, turned pro early in 1995 and quickly became one of the stars of “Blow by Blow,” a boxing show televised after Phillippine basketball games. Later that year, a friend of Pacquiao’s named Eugene Barutag was knocked out by Randy Barugan and collapsed in his corner. With no medical help at ringside, Barutag died.

The fact that Pacquiao could make it to even one championship was herculean. The fact that he now owns mansions throughout the Phillippines and a house in Los Angeles’ leafy Hancock Park neighborhood is one of modern sport’s great miracles.

“I saw a girl on the street there and gave her 1,000 pesos,” Roach said. “Then I thought, maybe I shouldn’t have done that. It’ll just mean someone will rob her later.”

Angelo Merino teaches a Phillippine Studies class at the University of San Francisco and is also the coach of the Dons’ intercollegiate boxing team. Like many Filipinos, he sees a lot of different things in Pacquiao’s blank stare, and sometimes the champion frustrates him.

But Merino is never unaware of what Pacquiao means.

“He is the man who put our country on the map,” Merino said. “Manny above everything else is a symbol of hope. When our people see him, they say, ‘Maybe I can do this, too.”’

***

Pacquiao shrugs off the many tentacles that the world sends his way. His friends have seen him stand in broiling sun, signing autographs for 5,000 Filipinos without blinking.

When he got to the Fox Network studios on this day, the producers had a surprise for him. They had written a song about how badly the NFL was missed during the off-season and they wanted Pacquiao to sing it for the upcoming pre-game show during Week 1. Although some of his handlers grumbled, Pacquiao listened to a tape of the verse, read the cue cards and performed it without complaint.

Back in the van, Pacquiao was asked how he puts boxing in perspective at age 35.

“I fight to inspire the people,” he said. “I know that I can’t go to the mall or shop by myself, even in Los Angeles. It’s OK. I’m a champion, so it’s a good thing. It’s good to be popular. I can use it to inspire.”

But Roach had been hoping to nudge Pacquiao into retirement before the fourth fight with Marquez on Dec. 8, 2012. Pacquiao was involved in Phillippine politics, his marriage to his wife Jinkee was increasingly turbulent and there were gambling and other late-night temptations.

He had barely survived Marquez the year before. A noticeably stronger Marquez knocked him down early in the 2012 fight. Pacquiao then rallied, broke Marquez’s nose and had him wobbling at the end of the sixth round. Roach was and is convinced that Marquez would not have left his stool when Round 7 began.

It did not get that far. Just before the bell, Pacquiao’s right foot and Marquez’s left foot got together and Pacquiao strayed right into the strike zone. Marquez’s perfect right hand put Pacquiao down on his chest. There was no need to count.

Within the tumult, Pacquiao did not move for several poignant seconds. Then he rose, smiling, and left the ring with no apparent damage. What Pacquiao knew, and what nobody else knew, is that he foresaw that ending.

“God showed me what would happen, the previous week,” Pacquiao said. “If you see the reaction on my face, there’s no reaction. I’m smiling. It has happened.”

Yes, but how does that explain the fact that Pacquiao was probably five seconds away from one of his greatest wins?

“That was just part of it,” he said. “God was testing my faith and belief. It was time for me to be a real Christian. What I saw the previous week, it happened.”

After Pacquiao got up, he wore a T-shirt that said, “Finished Business.” That immediately seemed like Pacquiao’s retirement statement. Instead, he took a layoff of nearly 12 months and in late November of 2013 he professionally disposed of Brandon Rios. Five months later he outboxed Tim Bradley, who had been awarded a boo-worthy decision over Pacquiao in 2012. He looks as quick and precise as he did in the 2008-09 period of dominance.

And, to the extent anyone can tell, he seems content.

“I committed to God in 2010,” he said, riding along toward the ESPN studios. “It’s how I live my life. I read the Bible every day. Something happened in my life. Yeah, I was struggling but I wanted to stop all the things that were troubling me, in God’s sight.”

Among his favorite verses is Romans 6:13: “Do not let any part of your body become an instrument of evil to serve sin. Instead, give yourselves completely to God, for you were dead, but now you have new life. So use your whole body as an instrument to do what is right for the glory of God.”

This, said Merino, is what frustrates many Filipinos.

“He was a Roman Catholic his whole life,” Merino said. “Our country is overwhelmingly Catholic. Now he’s a born-again Christian, he’s involved in faith healing. He used to observe Mass before his fights.

“It’s like basketball. He coaches the team (the Kia Sorrentos, of the Phillippine Basketball League) and now he’s the first-round draft pick and he’s short even for a Filipino and he’s 35 years old. And it’s like politics. People talk about how he’s going to be president of the Phillippines, and there’s no way. Back home they look at him and say, ‘Who decided that you are going to be a special leader?’ I love the guy, we all love the guy. But why is he doing all these things? He is a boxer first.”

Pacquiao was re-elected as a congressman in 2013, running unopposed. Roach also is wary of Pacquiao’s political future.

“I never saw a Filipino politician who wasn’t rich,” he said. “The only reason Manny won’t be president is that he wants to help people. The politicians don’t want to do that. That’s what I worry about. Somebody might shoot him because of that.”

One of Pacquiao’s campaigns is to address human trafficking in the Phillippines. Estimates are that 300,000 to 400,000 women are victims every year and 80 percent of all victims are girls younger than 18.

“Those kids are in danger,” Roach said. “I had a big van over there one day and about 13 kids wanted me to give them a ride to where Manny was training. There were a couple of parents there, but I thought, ‘This is what human trafficking is.’ Anybody who has a better offer, they’ll go there. Maybe they won’t come back. It didn’t dawn on me until I got about halfway to camp. I thought, ‘You know, maybe this isn’t the best idea in the world.'”

***

They return to the Phillippines to prepare for Algieri. The training process is sometimes the first reason for boxers to retire. But maybe it’s where Pacquiao’s inner fiber is most visible. Roach has said he will give him one day off to play for the Sorrentos, but that’s it.

The rest of it is sparring and training on the accelerated level that is demanded of 35-year-olds. Some of the sparring partners are not just in there for a “friendly,” like Ruslan Provodnikov used to be, like Frankie “Pit Bull” Gomez is now. They test Pacquiao and he answers.

Algieri, the undefeated college grad from Long Island, New York, has fun beating Pacquiao at pool and bowling on their media tours. He plays the nothing-to-lose card. Pacquiao just smiles and says nothing.

He was just as taciturn when Mayweather, trying to bait him before a proposed fight in 2010, said he would “cook that little yellow chump” and force him to “make me a sushi roll and some rice.”

Merino sees that stone face and smiles. He says Filipinos have developed that stoicism through centuries of colonialism, by the Spanish and the Americans, and the Japanese invasion in World War II. Ferdinand Marcos held the country in his grip until the People Power Revolution in 1986.

“That is a major part of our history,” he said. “We’ve been the victims of oppression. The Filipinos hold grudges. But we are able to adapt to situations. We don’t give away much with our expressions, not much beyond yes and no.

“Manny is like that. He will just say, ‘I’ll see you in the ring.’ But if he ever fights Mayweather, he will remember everything that has happened over the years and all the things he’s felt.”

There’s something special about the violence of a peaceful man.