Rios makes up for lost time

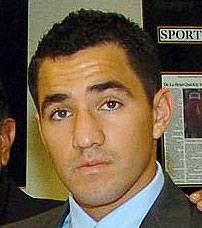

Let there be no doubt about Ronny Rios' ferocity when he has an opponent on the ropes. Photo / Paul Gallegos

***

FIGHT NIGHT CLUB: THE FACTS

What: Fight Night Club, a monthly boxing series featuring rising prospects at Club Nokia in downtown Los Angeles

Who: The featured young fighters hail from Southern California and beyond and all of them have the potential to be successful.

When: Thursday, July 30.

TV/Internet: The card will be televised on Versus and streamed live on RingTV.com and Yahoo! Sports. The first fight begins at 7 p.m. PT / 9 p.m. ET.

Future shows: Aug. 27 and Sept. 24 at Club Nokia, which is adjacent to Staples Center.

***

Ronny Rios has covered a lot of ground in a relatively short time.

Most successful professional fighters take up the sport shortly after they’re weaned off the bottle. Rios started as a teen-ager, at 13, which might’ve left him hopelessly behind his peers in terms of fundamentals and experience.

Rios appears to be a born fighter, though, the kind who adapts quickly and is afraid of nothing. He developed so quickly that he narrowly missed making the 2008 U.S. Olympic team, losing a controversial decision to eventual Olympian Gary Russell Jr.

As a pro, Rios, only 19, is 5-0 (with two knockouts). He faces journeyman Rodrigo Aranda in a four- or six-round bantamweight bout on the second “Fight Night Club” card Thursday at Club Nokia in L.A.

“I’ve always just tried to work on my technique more than anything else,” Rios said. “And conditioning; I run a lot. I also have fast hands; that’s what everyone says. I know fast hands and power only take you so far, though.

“A perfect fighter has the technique. Every day, I work on my foot work, throwing punches properly, turning them over, blocking and shooting. All the hard stuff.”

Rios wasn’t interested in boxing when he went to spend vacation with his Uncle Ramiro, who happened to be a boxing fanatic.

The boy picked up some boxing magazines, started reading and was intrigued. He said he was attracted by two catchy names – Vernon Forrest and Sugar Shane Mosley – and thought, “I want to see my name there.”

“I started talking to my uncle, I got into watching video tapes and then my brother started boxing,” he said. “So my uncle took me to Jerome (Memorial Recreational) Center in Santa Ana, which is where I met (trainer) Hector (Lopez).

“I didn’t know it was going to go this far. It just happened.”

It happened because Rios was a special talent.

To give you an idea how talented, he won the first amateur tournament in which he competed even though he had had only a few scattered bouts to his credit. Some of the boys he beat had 50, 60 fights experience.

Lopez said Rios began sparring with professionals the following year and generally held his own.

“The guys he sparred with would say, ‘No way that is kid is 14,'” Lopez said. “A 14-year-old giving hell to pros that early is really something. He told me the first week he walked into the gym that he was going to be a champion in multiple weight classes.

“I’ve been doing this for 20 years. Most kids tell me they want to be a world champion. Whatever. He said he wanted something like five different championships in five weight classes. That’s unheard of.”

Lopez corroborated what Rios said about his obsession with technique. And, yes, Rios has ridiculous hand speed, which is ideal in light of his signature punch: the jab.

“I would say Ronny is a boxer-puncher,” Lopez said. “If anything, he probably needs to learn to back off a bit. I don’t think he’s developed man strength at 19 that some other guys have. He needs to utilize his speed. He has unbelievable speed, which gives him an unbelievable jab. That’s unusual these days.

“Everyone wants to be an ESPN highlight with a roundhouse or something. Ronny is a disciplined kid, though. He works well behind that jab. And that speed. I’ve only seen on guy faster, Russell.”

Rios’ one great disappointment was his failure to make the Olympic team.

He was only 17, not even old enough to vote, when he faced Russell for the right to fight in the championship round of the Olympic trials. Rios and Lopez – and everyone else, Lopez said – thought Rios, the national champion at the time, won easily but Russell got the decision.

Russell went on to make the team but failed to make weight and didn’t compete.

“I thought I got the better of it,” Rios said. “The judges say he took the fight. I don’t know. It wasn’t really as disappointing as you might think. In your mind, once you feel you’ve won, it’s not that disappointing to actually lose it. I wasn’t as devastated as Hector was.

“For me, it was more devastating to see Hector hurt. He felt he failed me. I don’t think I could’ve done anything else.”

At Lopez’s urging, Rios resisted turning pro immediately after that fight even though he was eager to help his mother financially. He was a kid; Lopez felt he should let his body mature and get more seasoning.

All he did was repeat as U.S. national champion at bantamweight, after which he was deemed ready for the next step.

Rios received an offer from Top Rank but decided to go with manager Frank Espinoza, who handled gym mate Luis Ramos, and ultimately signed a promotional contract with Golden Boy Promotions.

“I sat Ronny down and said, ‘Listen, if you’re as good as you can be, it doesn’t matter who you sign with. I don’t care of its Golden Boy, Top Rank, Don King, doesn’t matter.’ We just wanted the opportunity like anyone else.

“And once Ronny gets an opportunity, he’ll definitely be a world champion.”

Michael Rosenthal can be reached at [email protected]