Ali-Quarry remembered

Forty-three years ago this week, one of the most anticipated comebacks in boxing history began when Muhammad Ali emerged from a 43-month exile to score a three-round TKO over Jerry Quarry. Ali’s return wasn’t just a sporting spectacle but it also was a social happening that struck at the heart of a deeply divided nation.

The athletic portion of the equation was easy to grasp. In many minds Ali remained the genuine heavyweight champion of the world because he never lost his title to another fighter inside the ring. To Ali’s supporters, Joe Frazier’s claim to heavyweight supremacy was a jurisdictional asterisk. He might have possessed the physical belt but until he beat the “man who beat the man,” the man known as “Smokin’ Joe” wasn’t going to receive their unvarnished certification. For years, a Frazier-Ali dream match remained just that, a dream. But once Ali’s return to the ring was confirmed, those dreams took a huge step toward becoming reality. The curiosity factor was huge, for rarely did an athlete emerge from such a lengthy hiatus while still in his 20s.

The sociological part was far more complex – and far more turbulent. For years America’s involvement in the Vietnam War was the source of collective angst and the result was an intractably polarized populace. Neutrality wasn’t an option. A person had to choose which side of the fence he occupied and once that decision was made one was forced to wear the labels associated with it.

Ali was no stranger to unpopular choices. Immediately after shocking the world by stopping Sonny Liston in Miami  Beach to become world heavyweight champion, he compounded the effect with a two-pronged proclamation. First, he declared to the public at large for the first time that he was a member of the Nation of Islam, also known as the “Black Muslims,” and second, he no longer wished to be called by his birth name – Cassius Marcellus Clay – but would rather be addressed as “Cassius X,” with the “X” representing his race’s lost identity. Shortly thereafter, Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad renamed him Muhammad Ali and while some assimilated the switch immediately many in the mainstream sporting press continued to call him “Clay,” as much out of fury as anything else. For the next several years Ali was a magnet for controversy and strife, both in and out of the ring.

Beach to become world heavyweight champion, he compounded the effect with a two-pronged proclamation. First, he declared to the public at large for the first time that he was a member of the Nation of Islam, also known as the “Black Muslims,” and second, he no longer wished to be called by his birth name – Cassius Marcellus Clay – but would rather be addressed as “Cassius X,” with the “X” representing his race’s lost identity. Shortly thereafter, Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad renamed him Muhammad Ali and while some assimilated the switch immediately many in the mainstream sporting press continued to call him “Clay,” as much out of fury as anything else. For the next several years Ali was a magnet for controversy and strife, both in and out of the ring.

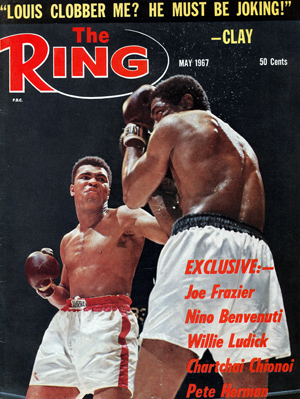

The WBA stripped Ali of its recognition on Sept. 14, 1964, ostensibly because Ali had agreed to a rematch with Liston but most believed it was motivated by Ali’s alignment with the Nation of Islam. Ernie Terrell won the belt in March 1965 after he decisioned Eddie Machen, but Ali rancorously regained full recognition in February 1967 by torturing Terrell physically and verbally en route to an emotionally charged 15 round decision. More than any other fight, Ali used the ring to express his anger and frustration with those who opposed him. To him, Terrell was an appropriate and willing target because he, like Floyd Patterson before him, pointedly refused to call Ali by his chosen name. Patterson paid a heavy price for his insolence for 12 painful-to-watch rounds and so did Terrell, whose agony lasted the full 15. The post-fight sentiment was best captured by Tex Maule, who declared the Terrell dissection “a wonderful demonstration of boxing skill and a barbarous display of cruelty.”

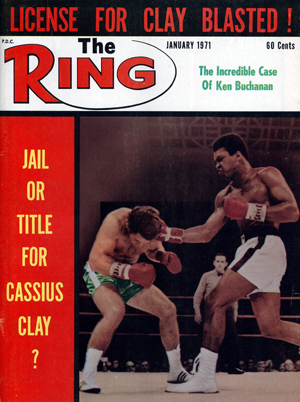

So when Ali planted his flag firmly in the anti-war camp by refusing induction into the U.S. Army on April 28, 1967, another war was ignited – one that would last three-and-a-half years and cost Ali the very best years of his athletic life. That same day the WBA and the New York State Athletic Commission stripped Ali of their titles and all boxing options vanished when every state commission revoked his boxing license and the U.S. government took away his passport.

Ten days after refusing induction he was indicted by a federal grand jury in Houston and he eventually was convicted of draft evasion, which carried a five-year prison sentence and $10,000 fine. The only jail time he served, according to Thomas Hauser’s excellent biography of Ali (“Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times”), was a week-long stint for driving without a valid license in Dade County, Florida. Otherwise, Ali remained free pending appeal of his conviction and he used the time to rally support through a series of college speeches and TV interviews.

When public sentiment began to turn against the war, so did the invisible walls that imprisoned Ali’s boxing career. A growing segment of the population recognized Ali’s vigilance and in many quarters he was transformed from a pariah to a towering political hero. The idea of a ring return became exponentially more attractive, though several attempts to secure a license resulted in dead ends.

So it was the height of irony that it was Atlanta, a city that occupied the heart of the Deep South, that provided the breakthrough. State Senator Leroy Johnson and Governor Lester Maddox helped pave the way for a most improbable return by persuading the City of Atlanta Athletic Commission to grant Ali a boxing license on Aug. 12, 1970. Shortly thereafter, it was announced Ali would fight Jerry Quarry on Oct. 26 at the City Auditorium in Atlanta. The bout was scheduled for 15 rounds, probably in recognition of Ali’s status as lineal heavyweight champion.

Nearly three months short of his 28th birthday Ali remained near his physical peak – at least chronologically. But one had to wonder how much the long layoff eroded his once supernatural skills. During his three-year reign in the mid-to-late 1960s, Ali possessed lightning hand speed, balletic mobility and finely honed reflexes that depended heavily on precise timing. Though Ali occasionally worked out during his exile, he had no reason to live “the life” of an elite athlete and because of that he surely had to have lost something off his considerable fast ball.

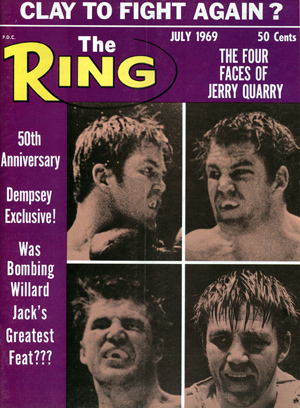

Then there was Quarry, who was rated the number-one heavyweight in the world by THE RING going into the fight. His 34-4-4 (23) record included victories over Brian London (W 10, KO 2), Alex Miteff (KO 3), Floyd Patterson (W 12 in their rematch), Thad Spencer (KO 12), Buster Mathis (W 12) and Mac Foster, who carried a 24-0 (24) record before Quarry starched him in six rounds. The “Bellflower Belter” wielded a massively powerful left hook and a fistic fervor that rivals that of anyone who ever stepped inside the ring. He had lost two previous chances at a heavyweight title, a 15-round majority decision to Jimmy Ellis in the WBA elimination tournament final and a pulse-pounding seventh round TKO to NYSAC king Joe Frazier in THE RING’s Fight of the Year for 1969, but entering the Ali fight he was riding a four-fight winning streak. At 25, he was three years younger than Ali and was, in fact, the first younger opponent Ali had faced as a pro and only the second born after 1940 (Sonny Banks, nearly 18 months older, was the other).

Then there was Quarry, who was rated the number-one heavyweight in the world by THE RING going into the fight. His 34-4-4 (23) record included victories over Brian London (W 10, KO 2), Alex Miteff (KO 3), Floyd Patterson (W 12 in their rematch), Thad Spencer (KO 12), Buster Mathis (W 12) and Mac Foster, who carried a 24-0 (24) record before Quarry starched him in six rounds. The “Bellflower Belter” wielded a massively powerful left hook and a fistic fervor that rivals that of anyone who ever stepped inside the ring. He had lost two previous chances at a heavyweight title, a 15-round majority decision to Jimmy Ellis in the WBA elimination tournament final and a pulse-pounding seventh round TKO to NYSAC king Joe Frazier in THE RING’s Fight of the Year for 1969, but entering the Ali fight he was riding a four-fight winning streak. At 25, he was three years younger than Ali and was, in fact, the first younger opponent Ali had faced as a pro and only the second born after 1940 (Sonny Banks, nearly 18 months older, was the other).

But as stout as Quarry’s fighting heart was, his brows were equally brittle. The Frazier fight was stopped between rounds seven and eight due to severe cuts around Quarry’s eyes and win or lose he often had to fight with compromised vision. His chin also was vulnerable, for he was dropped in fights with Roy Crear (KO 3), Al Jones (KO 5), Patterson in fight one (D 12) and Rufus Brassell (KO 2). That he went 3-0-1 in those bouts spoke well of Quarry’s perseverance and though Ali boasted 23 knockouts in his 29-0 record he never was, the Liston rematch notwithstanding, a one-punch knockout artist.

A sell-out crowd of more than 5,000 jammed into the City Auditorium to witness an event some equated to a Second Coming.

“It was like nothing I’d ever seen,” former NAACP chairman Julian Bond told Hauser. “The black elite of America was there. It was a coronation; the King regaining his throne. The whole audience was composed of stars; legitimate stars, underworld stars. You had all these people from the fast lane who were there, and the style of dress was fantastic. Men in ankle-length fur coats; women wearing smiles and pearls and not much else. It was more than a fight, and it was an important moment for Atlanta, because that night, Atlanta came into its own as the black political capital of America.”

The 197¾-pound Quarry entered the ring first in a resplendent aqua robe to a smattering of applause. The Californian couldn’t have cared less about the tepid reception because he was there to do a job and do it well. He respected Ali but didn’t fear him and the $300,000 purse (of which he kept $95,000 after taxes) was far and away the largest of his career to that point.

A couple of minutes later, Ali bounded down the aisle to thunderous cheers mixed with barely discernable boos. At 213¾, Ali appeared in exquisite condition. After ring announcer Johnny Addie introduced a trio of former champions – Ike Williams, Jose Torres and Jimmy Ellis – as well as Sen. Johnson and the participants, Ali and Quarry were brought to ring center for the final instructions from referee Tony Perez. Quarry leaned into Ali’s face and radiated stone-faced confidence, which prompted Ali to say, among other things, “you’re in trouble.” Ali’s inattentiveness combined with the din inside the arena prompted Addie to ask the crowd to settle down, and while the throng obeyed for a few moments nothing could cap the energy forever. The sound of the opening bell was all that was needed to unleash the pent-up emotions that had been building for more than three years.

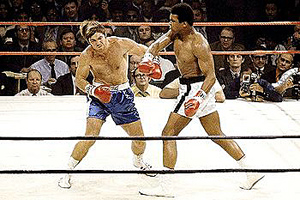

Quarry met Ali three-quarters of the way across the ring but after a stutter-step designed to intimidate Ali, Quarry aborted his charge and began a more conventional pursuit. Ali, as expected, was on his toes, gliding about the ring with his trademark grace. His first flurry – a jab-cross-double hook – mostly missed the mark but confirmed he still had much of his hand speed. Ali’s defensive radar was also in fine form as he snapped his head back at every hint of an impending Quarry attack. Within a minute Ali had found his range with the jab while Quarry continued to stalk and survey. Another good sign for Ali was that a lead right, a staple of his attack, landed well, and that a split-second later he was able to lean away from Quarry’s lead right.

Quarry met Ali three-quarters of the way across the ring but after a stutter-step designed to intimidate Ali, Quarry aborted his charge and began a more conventional pursuit. Ali, as expected, was on his toes, gliding about the ring with his trademark grace. His first flurry – a jab-cross-double hook – mostly missed the mark but confirmed he still had much of his hand speed. Ali’s defensive radar was also in fine form as he snapped his head back at every hint of an impending Quarry attack. Within a minute Ali had found his range with the jab while Quarry continued to stalk and survey. Another good sign for Ali was that a lead right, a staple of his attack, landed well, and that a split-second later he was able to lean away from Quarry’s lead right.

His confidence rising, Ali repeatedly speared Quarry’s face with jabs and one-twos, with the heavily pro-Ali crowd ooh-ing and aah-ing with each connect. Quarry’s hooks were well off the mark and the reddened area near the bridge of his nose was proof positive of Ali’s early effectiveness. A five-punch salvo followed by a flush lead right bedazzled Quarry, who seemingly had no answer for the darting speed demon that circled him. Worse yet the 6-foot-tall Quarry was three inches shorter and had a wingspan 10 inches shorter, which meant that he had to dive into the buzz saw in order to score. Quarry finally landed his first notable punch – a lead right to the face – more than two-and-a-half minutes into the fight but it had no discernable effect on Ali, who capped the round by landing four more jabs, each more stinging than the last.

At the gong, the crowd let out a huge cheer. The shroud of mystery had been removed and what was revealed that, at least so far, their man had many of the same gifts as before. Ali’s jabs created small abrasions below both Quarry eyes while Ali’s face was as unmarked as ever.

With Drew “Bundini” Brown shouting “all night long,” Ali opened the second much like the first – jabs, jabs and more jabs, many of which found Quarry’s face like a magnet finds a piece of metal. A looping Quarry hook found its mark but Ali retaliated with a slapping six-punch bouquet. Ali leaned away from several dangerous-looking hooks and a third one that barely missed appeared particularly threatening.

Quarry began to find his own rhythm as a hook struck the side of Ali’s head and a long lead right to the ribs connected. Through it all, Ali remained faithful to his pattern of circling, jabbing and sniping at every opportunity but now that Quarry had experienced some success the event was turning more into a fight. As the second round closed each man struck with their best weapons time and again. In fact, a sticky Quarry hook to the body marked the stanza’s final punch.

As the third round opened Quarry continued to fire – and miss – his left hook while Ali was content to circle left and right. Ali’s landed jabs produced a resonant sound around ringside and all seemed well. But then Quarry finally managed to maneuver Ali to the ropes and land his best punch of the fight, a heavy hook to the stomach that forced a clinch. By then Quarry had a new mark on his face, a reddish blotch above the right eye, yet while his face was blemished his desire was unaffected.

One hundred seconds into the round, Ali landed the punch that irreparably turned the fight his way – a razor-sharp jab that ripped the scar tissue above Quarry’s left eye. As soon as Quarry felt the warm crimson drip down his face he lunged in desperately and fired both hands only to have Ali lock his arms. When the two fighters pulled away only then did everyone realize the severity of Quarry’s injury, as well as the urgency of his situation. This was a fight-stopping cut and Quarry realized he had less than 90 seconds to get the job done.

One hundred seconds into the round, Ali landed the punch that irreparably turned the fight his way – a razor-sharp jab that ripped the scar tissue above Quarry’s left eye. As soon as Quarry felt the warm crimson drip down his face he lunged in desperately and fired both hands only to have Ali lock his arms. When the two fighters pulled away only then did everyone realize the severity of Quarry’s injury, as well as the urgency of his situation. This was a fight-stopping cut and Quarry realized he had less than 90 seconds to get the job done.

Ali targeted the gash with a jab and lead right, both of which connected. Now it was Ali who moved forward and positioned Quarry on the ropes, where he landed yet another right to the cut. For all the questions that had already been answered, it now was evident that Ali’s targeting system was in fine working order. A solid one-two and another heavy right blasted through, causing Quarry to back off and brush away the spurting liquid. Quarry landed a solid right to the body but Ali walked through it and responded with his own hefty right to the cut. For most of the contest Ali had been the hunted but now he was the remorseless pursuer that hungered for a briefer-than-expected evening.

At round’s end the left side of Quarry’s face was a mess and his head-down, hunched-over posture reflected his discouragement. Referee Perez monitored the situation as Quarry’s seconds worked over the cut. But only 20 seconds into the rest period the fighter leaped off the stool as if launched by rocket fuel. The reason for Quarry’s reaction was that Perez had stopped the fight, affixing Quarry’s fifth loss and confirming Ali’s 30th victory.

At first Quarry’s rage appeared beyond control but after tearing himself from the grip of his chief second he circled the ring and approached Ali. In those few steps Quarry’s anger was replaced by sportsmanship while a compassionate Ali reached out with arms outstretched. As they embraced they exchanged words and given their expressions they were benign and probably congratulatory. What could have been a moment of rancor instead turned into one of respect. After the fight, Quarry made it a point to confirm that the cut was created by a punch, not a butt.

When the crowd realized the fight was over they exploded with rapturous glee. Their hero had cleared a considerable hurdle in his quest to regain the crown that was taken from him, and he achieved it with his usual flamboyance.

When the crowd realized the fight was over they exploded with rapturous glee. Their hero had cleared a considerable hurdle in his quest to regain the crown that was taken from him, and he achieved it with his usual flamboyance.

“Quarry was tricky, he hit hard and if it wasn’t for my speed it wouldn’t have ended the way it did,” Ali said after the fight. “I managed to miss just a few punches – he didn’t hit me but about once or twice, and that was to the body (and) not in the face. I’m a little stronger now than I was the day I retired and I think I’m a much better fighter now. I’m sorry the cut did happen because I didn’t really get enough action. Three rounds isn’t enough.”

With Quarry now out of the way, Ali also addressed the raging question of the moment: When will he fight Frazier for the undisputed crown?

“I’m glad that I am back so we can settle this confusion about Joe Frazier and all the people who think he’s still the champion and I hope something can soon be worked out where we can solve this heavyweight mess,” Ali said. “It’s up to the managers and the backers, we got a couple of more things in the works and we’re not too anxious to get to him. He’s got to get past Bobby Foster, the light heavyweight champion, first.”

Frazier not only got by Foster, he destroyed him. He finished the bout in round two with a pulverizing hook to the chin that knocked the future Hall of Famer into unconsciousness. Meanwhile, Ali immediately returned to the gym to prepare for another stern challenge in Oscar Bonavena, who gave Ali fits before falling in the 15th. With those hurdles out of the way, nothing stood in the way of the fight the world wanted most – The Greatest versus Smokin’ Joe.

Additional sources:

“Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times” by Thomas Hauser

“The Great Book of Boxing: The Illustrated History of Boxing From the 1890s to the Present,” by Harry Mullan

*

Photos / THE RING

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, W.Va. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 10 writing awards, including seven in the last three years. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. He is the author of “Tales From the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics. To order, please visit Amazon.com or e-mail the author at [email protected] to arrange for autographed copies.