Someone’s ‘O’ has got to go: 10 notable fights between unbeaten fighters – Part II

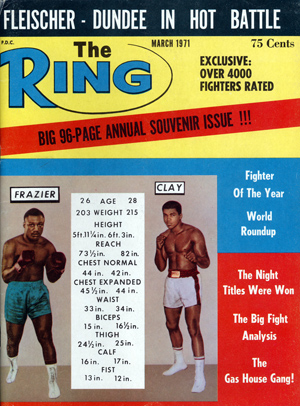

1. March 8, 1971 — Joe Frazier (26-0) W 15 Muhammad Ali I (31-0), Madison Square Garden, New York, N.Y.

It was a fight unlike any other in boxing history. Joe Frazier and Muhammad Ali had unblemished records and each could accurately describe himself as the undisputed heavyweight champion of the world. Ali dethroned Charles “Sonny” Liston in February 1964 and had successfully reunited the titles by beating WBA titleholder Ernie Terrell three years later after that body stripped Ali the first time. When Ali refused to serve in the U.S. Army during the Vietnam War and claimed conscientious objector status as a Muslim minister, the worldwide boxing commissions responded by stripping Ali’s title and revoking his license. Politics, not pugilists, had taken his crown.

Once Ali’s exile began, the WBA staged an eight-man elimination tournament to fill its vacancy and in April 1968 Jimmy Ellis, a longtime sparring partner of Ali’s, emerged victorious after out-pointing Jerry Quarry in the final. Meanwhile, the New York State Athletic Commission matched Joe Frazier and Buster Mathis for its version of the title, which also would be recognized by Illinois, Maine and Massachusetts. Frazier, who replaced Mathis on the 1964 Olympic team due to injury and won the gold medal, won by 11th round knockout to fill that void.

Ellis and Frazier met for the undisputed title in February 1970 and “Smokin’ Joe” won by fifth-round TKO. But Frazier wasn’t allowed to enjoy his accomplishment, for many believed Ali was still the “real” champion because he had never been beaten for the belt. Ali’s legal issues had long prevented the dream match from happening but after public sentiment turned against the war the stone walls began to crumble.

Ellis and Frazier met for the undisputed title in February 1970 and “Smokin’ Joe” won by fifth-round TKO. But Frazier wasn’t allowed to enjoy his accomplishment, for many believed Ali was still the “real” champion because he had never been beaten for the belt. Ali’s legal issues had long prevented the dream match from happening but after public sentiment turned against the war the stone walls began to crumble.

On Aug. 12, 1970 Atlanta’s athletic commission granted Ali a license to box and on Oct. 26 he defeated top contender Jerry Quarry on cuts in three rounds. The New York commission then followed suit and as a result Ali returned to Madison Square Garden and stopped Oscar Bonavena in the 15th round to cement his status as Frazier’s top challenger – or, in many eyes, retained his status as lineal heavyweight champion. Frazier fortified his claim one month earlier when he crushed reigning light heavyweight champion Bob Foster in two rounds.

Once Frazier and Ali signed a contract paying each a flat fee of $2.5 million, the “Fight of the Century” was finally on.

Not only was the fight a global sporting attraction, it was deeply enmeshed in politics. Ali already was a hero to the anti-war counterculture for his vocal and principled stand while Frazier was embraced by the establishment only because he was the one person on earth legally authorized to hit him on March 8, 1971.

Frazier’s animus toward Ali wasn’t political, but rather deeply personal. When Ali was in exile Frazier befriended him and even loaned him money from time to time. But now that Ali had his license back he felt free to unload all his verbal weaponry and Frazier, as was the case with all of Ali’s opponents, were ill-equipped to match words and wits with him. Ali insisted he was just trying to enhance the gate but Frazier was rightly skeptical because their share of the money was fixed and guaranteed.

During the pre-fight build-up Ali’s barbs crossed lines he seldom approached in other bouts. One such example was cited in Tom Hauser’s excellent biography of Ali. At one appearance Ali said “the only people rooting for Joe Frazier are white people in suits, Alabama sheriffs and members of the Ku Klux Klan. I’m fighting for the little man in the ghetto.” As Ali said this, Frazier, who escaped an impoverished upbringing in South Carolina, smashed his fist into the palm of his hand and muttered “what the f*** does he know about the ghetto?”

With every insult the level of Frazier’s anger escalated and by fight time it was at a murderous boiling point. One Ali fan felt the same way about Frazier as, according to the New York Times, he issued a “lose or else” death threat.

Frazier scaled a hard 205¾ while Ali, three-and-a-half inches taller and owning a five-inch reach advantage, weighed 215. Just before leaving his dressing room Ali unveiled his prediction of a sixth round knockout to a worldwide closed-circuit audience estimated at 300 million and the 20,455 fans that jammed inside Madison Square Garden. The $1,352,951 in gate receipts represented a new indoor record.

The star-studded arena was ready to explode as the two fighters waited in their corners for the opening bell. Once it sounded, an unforgettable war proceeded to unfold.

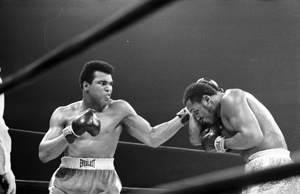

Knowing Frazier was a habitually slow starter, Ali jumped on his rival and ceaselessly fired combinations at his bobbing target while Frazier took every opportunity to throw, and land, his trademark hooks. Each set a torrid pace and within it each man tried to exploit their respective advantages – Ali with speed, footwork and sharp counter-punching, Frazier with relentless aggression and bone-crushing blows to the head and especially the body. Ali’s frequent chattering could be heard through the microphone that hung over the ring while Frazier opted to let his fists do the talking.

Knowing Frazier was a habitually slow starter, Ali jumped on his rival and ceaselessly fired combinations at his bobbing target while Frazier took every opportunity to throw, and land, his trademark hooks. Each set a torrid pace and within it each man tried to exploit their respective advantages – Ali with speed, footwork and sharp counter-punching, Frazier with relentless aggression and bone-crushing blows to the head and especially the body. Ali’s frequent chattering could be heard through the microphone that hung over the ring while Frazier opted to let his fists do the talking.

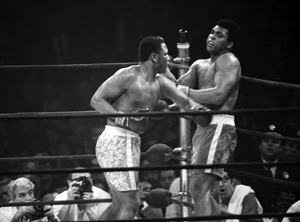

But as heated as the fighting was, the non-verbal war was just as fierce. After Frazier landed a particularly meaty hook Ali grabbed the back of his opponent’s neck, peered into the audience and shook his head to assure his fans he was unharmed while at separate points Frazier laughed at Ali’s punches, cuffed him atop the head and sneered at him. Before another round, Ali swept his glove toward the crowd to indicate to Frazier that this was his audience. Frazier replied by pointing his glove toward the canvas as if to say “you may own the crowd, but I own the ring.”

The early-round punishment already was taking a toll on each man. Ali’s combinations raised swellings around Frazier’s eyes and bloodied his mouth while Ali’s injuries, aside from a minor nosebleed, were mostly hidden. Frazier’s wrecking-ball hooks to the ribs saw to that. The action was so heated that, according to the New York Times’ Dave Anderson, one person in the audience died from a heart attack.

The early-round punishment already was taking a toll on each man. Ali’s combinations raised swellings around Frazier’s eyes and bloodied his mouth while Ali’s injuries, aside from a minor nosebleed, were mostly hidden. Frazier’s wrecking-ball hooks to the ribs saw to that. The action was so heated that, according to the New York Times’ Dave Anderson, one person in the audience died from a heart attack.

The tremendous pace slowed in the middle rounds, mostly because Ali chose to use a prehistoric version of the “Rope-a-Dope.” One particularly lengthy segment along the strands brought loud boos from the crowd and at one point a frustrated Frazier wrapped both gloves around Ali’s wrists and forcibly pulled him out to ring center.

While some thought Ali was playing, Frazier knew otherwise.

“Clowning?” Frazier asked. “He couldn’t move. Those body shots had slowed him down.”

Frazier’s already swollen face received an unwelcome surprise in the 10th when referee Arthur Mercante Sr. accidentally poked Frazier in the eye with his pinkie while separating the fighters. He motioned toward his corner to register his distress and the official issued an immediate apology.

Frazier broke open a close fight late in the 11th when a short hook to the point of Ali’s jaw buckled the former champion’s legs and nearly floored him. Ali’s reputation for play-acting was so well established that his faux wobble was enough to keep Frazier from following up fully. The move bought Ali time, but only for a while. In the later rounds, Frazier’s hooks raised a massive swelling on Ali’s right cheek.

Frazier broke open a close fight late in the 11th when a short hook to the point of Ali’s jaw buckled the former champion’s legs and nearly floored him. Ali’s reputation for play-acting was so well established that his faux wobble was enough to keep Frazier from following up fully. The move bought Ali time, but only for a while. In the later rounds, Frazier’s hooks raised a massive swelling on Ali’s right cheek.

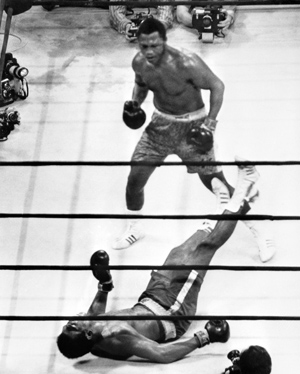

Any doubts about the final result evaporated early in the 15th round when Frazier countered Ali’s right uppercut with a destructive hook to the swollen jaw. Ali’s tasseled shoes flew into the air and for an instant he appeared to be out.

But Ali’s massive pride demanded that he regain his feet instantly, and to nearly everyone’s surprise he hustled to his feet by Mercante’s count of four. He also managed to put together a mini-rally in the final minute but his efforts were far too little and far too late. At the final bell, a bloody-mouthed Frazier yelled something at Ali, who simply turned away and walked to his corner.

But Ali’s massive pride demanded that he regain his feet instantly, and to nearly everyone’s surprise he hustled to his feet by Mercante’s count of four. He also managed to put together a mini-rally in the final minute but his efforts were far too little and far too late. At the final bell, a bloody-mouthed Frazier yelled something at Ali, who simply turned away and walked to his corner.

“He called me a lot of names,” he told Deane McGowen of the New York Times in the post-fight press conference. “I wanted him to come to me after the fight and apologize. But he just mumbled something and turned to his corner.”

The decision was unanimous as Frazier won 11-4, 9-6 and 8-6-1 under the rounds system. It was the third time Frazier had to prove himself worthy of the title “undisputed heavyweight champion of the world” and his brilliant performance against Ali ensured that no doubters remained.

“I always knew who the champion was,” Frazier said with a swollen smile.

Ali didn’t attend the post-fight news conference, choosing instead to remain in his dressing room for 30 minutes before leaving for Flower-Fifth Avenue Hospital for X-rays. According to the New York Times‘ Dave Anderson, he departed approximately 40 minutes later and left without bandages.

“Don’t worry, we’ll be back,” Ali said through a media statement delivered by assistant trainer Drew “Bundini” Brown. “We ain’t through yet.”

He was right. Frazier and Ali weren’t through with each other – not by a long shot.

*

Photos / THE RING, AFP

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, W.Va. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 10 writing awards, including seven in the last three years. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. He is the author of “Tales From the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics. To order, please visit Amazon.com or e-mail the author at [email protected] to arrange for autographed copies.