Sugar Ray Robinson-Jake LaMotta VI: The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre 70 years later

Seventy years ago today, one of boxing’s most celebrated rivalries came to a emphatically violent end, an end that confirmed the winner’s pound-for-pound greatness beyond all doubt while also cementing the loser’s ruggedness, pride and unbreakable will.

The beating Sugar Ray Robinson dished out in rounds 12 and 13 of his sixth meeting with Jake LaMotta is the stuff of myth, and while director Martin Scorsese’s interpretation of that beating in Raging Bull was graphic and melodramatic, it accurately captured the essence of Robinson’s final drive toward his second world championship as well as LaMotta’s determination not to give his rival the satisfaction of becoming the first man in his 96-fight career to knock him down. The spectacle caused many of the fans inside Chicago Stadium to demand that the fight be stopped, and at the 2:04 mark of Round 13 referee Frank Sikora, at the behest of ringside physician J.M. Houston, officially ended what would become boxing’s equivalent of the “St. Valentine’s Day Massacre” thanks to the date and the nature of Robinson’s onslaught.

The final moments of their six-fight series –coupled with the 5-1 lead it finalized — created the impression that this rivalry wasn’t a rivalry at all. “Sure, LaMotta won the second fight,” they would say. “But Sugar Ray won all the rest, including their only fight for a world title, and he ended it by beating the living hell out of Jake.” A closer examination of the series — and of their sixth meeting — would reveal that LaMotta challenged the prime Robinson more consistently than any other opponent.

If one is to believe Robinson’s oft-quoted amateur record of 85-0 (69 KO) — some sources say he lost two simon pure bouts under his birth name of Walker Smith — then LaMotta’s win in fight two snapped what was an incredible 125-fight winning streak to begin Robinson’s boxing life. Additionally, LaMotta holds a 2-0 lead in terms of scoring knockdowns (he decked Robinson in Round 8 of his victorious second fight and in Round 7 of their third meeting, a tight 10-round decision for Ray) and Robinson said of their fifth meeting, a 12-round split decision in September 1945, “this was the toughest fight I’ve ever had with LaMotta.” The Bronx Bull’s hard-driving aggression, masterful infighting, rock-hard chin and marked weight advantage (an average of 12.6 pounds through their first five fights) forced Robinson to utilize 100 percent of his otherworldly talent, for anything less would never have sufficed.

Following the fifth fight of their series — all of which unfolded in a little less than three years — they pursued divergent paths. Because the titles were frozen during World War II — and because he refused to make deals with the organized crime figures that ran the sport — Robinson, though considered the best 147-pounder on earth for half a decade, was denied a title fight until December 1946 when he met Tommy Bell for the championship vacated by Marty Servo three months earlier. Servo had been scheduled to face Robinson for the belt that September, but a nose injury that eventually required surgery forced him to withdraw, then he announced his retirement. Robinson, the 5-to-1 favorite, overcame a second-round knockdown to notch one of his own against Bell in the 11th en route to a commanding points victory.

Although Robinson risked the belt only four times over the next four years — he stopped Jimmy Doyle, who tragically passed away due to the injuries he sustained, in eight rounds, halted Chuck Taylor in six, out-pointed Kid Gavilan over 15 and scored a lopsided points win over Charley Fusari — he extended his new unbeaten streak to 83 fights thanks to his string of non-title fights over middleweights. The only blemishes during this run were 10-round draws against Jose Basora in May 1945 and Henry Brimm in February 1949, but he entered the LaMotta match on a 31-fight string of wins, the most recent of which was a fifth-round TKO over Hans Stretz in Frankfurt on Christmas Day 1950. His record entering the bout was an incredible 121-1-2 (79 KO) — with the only loss coming against LaMotta.

Like Robinson, LaMotta did not want to be beholden to the mob, but when it became clear that working with the dark forces of the sport was the only way he would gain access to a championship fight, he eventually bent to their will by agreeing to throw his fight against Billy Fox in November 1947.

“I never had a manager,” LaMotta told author Peter Heller in February 1970. “A lot of these guys wanted to take care of me and I wouldn’t trust nobody. I deserved a chance for the title but because I had nobody to represent me — the ‘right kind’ of people, so they say — I did things on my own. I was uncrowned champ for five years. Nobody wanted to fight me, so I felt this was the only way I could get a chance. And I had to lose the fight, which I never wanted to do, but I was only a kid (he was actually 26) and I thought this was the way you had to do it.”

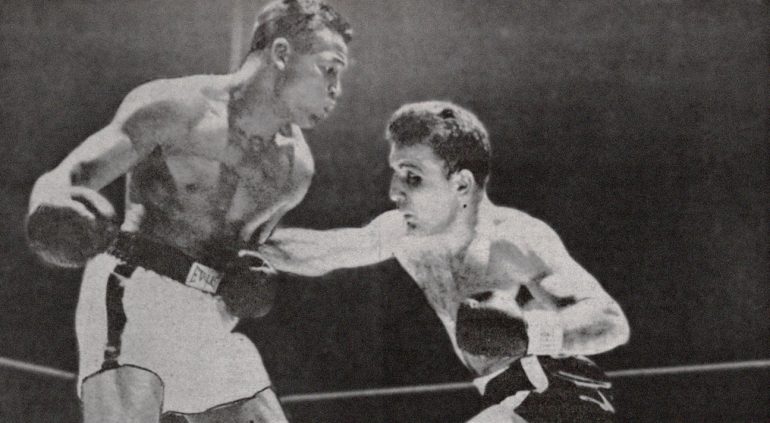

Photo from The Ring archive.

Word of the impending fix moved the line from a 6-to-5 pick-’em to 3-to-1 Fox in a matter of hours. Although he allowed himself to be battered by the hard-hitting Fox — who scored his 44th KO in 45 fights against one loss to then light-heavyweight champion Gus Lesnevich — he refused himself the indignity of being knocked down. That choice made the charade even more obvious, and the stench led to a fine and suspension from the New York State Athletic Commission.

“Exposing himself almost as flagrantly as Lady Godiva, Jake refused to go down but threshed and floundered on the ropes, apparently helpless against Fox’s blows, until the referee stopped them in the fourth round,” Red Smith wrote in 1980.

Despite his act of submission, LaMotta still didn’t get his championship match until June 1949. Then, to complete the arrangements for his fight against middleweight monarch Marcel Cerdan, LaMotta paid the “powers that be” an additional $20,000 (more than $800 more than his purse ended up being) and agreed to a three-year exclusive services contract with the International Boxing Club. LaMotta hoped to provide himself some financial wiggle room by betting on himself to win $6,000.

Following a one-day postponement due to rain, Cerdan-LaMotta was staged at Detroit’s Briggs Stadium. LaMotta’s cause was greatly helped when Cerdan, the 2-to-1 favorite, tore the muscles in his left shoulder after being thrown to the canvas in Round 1. Although Cerdan continued to use the arm, his effectiveness was clearly compromised. Meanwhile, LaMotta suffered a broken left hand in round four, but he fought through the pain and piled up the points thanks to accurate rights to the body. Following an examination by the Michigan commission doctor, Cerdan was unable to answer the bell for round 10 and LaMotta became the new middleweight champion of the world.

The contract called for an immediate rematch on September 28, 1949 but the fight was pushed back to December 2 after LaMotta injured his shoulder six days before the match. Tragically, LaMotta-Cerdan II would never take place, for Cerdan, who was traveling to the U.S. to train for the bout, was killed in a plane crash on October 27.

Following a non-title 10-round decision loss to Robert Villemain in December 1949, LaMotta scored victories over Dick Wagner (KO 9), Chuck Hunter (KO 6) and Joe Taylor (W 10) before notching successful title defenses against Tiberio Mitri in July 1950 (W 15) and previous conqueror Laurent Dauthuille two months later. Down on all cards entering the final round and looking as weak as a lamb, the Frenchman moved in for the kill. But as he did so, the New Yorker suddenly sprang into action by cranking a series of quick hooks and turning the challenger toward the ropes. Realizing he had just been fooled, Dauthuille tried to escape to ring center but LaMotta maneuvered his upper body to keep the challenger where he was and his fists to administer heavy damage.

LaMotta’s all-out attack escalated with each passing second and Dauthuille could do nothing to turn the tide. A savage hook left Dauthuille’s body draped over the bottom rope and the badly dazed challenger, knowing the title could still be his if he arose, did his best to regain his feet. He did so, but only a split-second after referee Lou Handler completed his count. It is ironic that LaMotta, a man given to superstition, retained his championship with just 13 seconds remaining in the contest. With the victory, LaMotta’s record stood at 78-14-3 (28 KO).

“I was very, very, very lucky to win that fight,” LaMotta said.

LaMotta’s incredible rally earned him a notable double — The Rings Fight of the Year and its Round of the Year. Only Round 6 of Tony Zale-Rocky Graziano II had previously pulled off that feat and it marked the only time LaMotta would win either award.

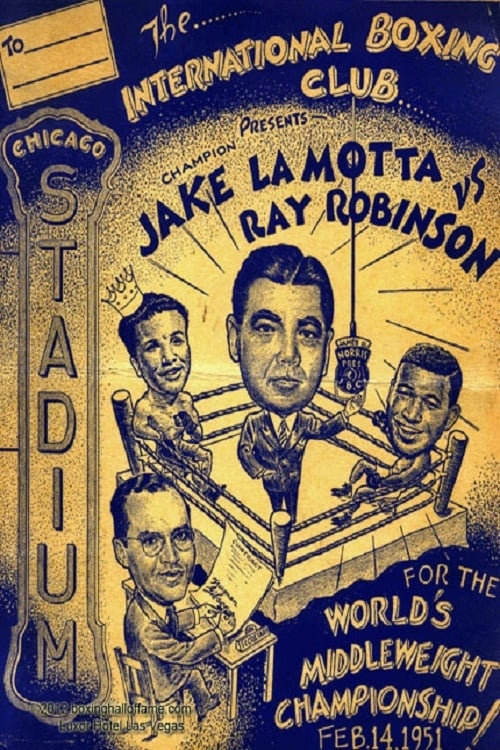

Five months after taking out Dauthuille, LaMotta defended the title against Robinson, the reigning welterweight champion. It would be the first title fight involving two undisputed champions since featherweight and welterweight champion Henry Armstrong completed his one-of-a-kind triple crown by dethroning lightweight champion Lou Ambers in August 1938, and given his record of success against LaMotta, Robinson was deemed a solid 14-to-5 betting favorite.

Five months after taking out Dauthuille, LaMotta defended the title against Robinson, the reigning welterweight champion. It would be the first title fight involving two undisputed champions since featherweight and welterweight champion Henry Armstrong completed his one-of-a-kind triple crown by dethroning lightweight champion Lou Ambers in August 1938, and given his record of success against LaMotta, Robinson was deemed a solid 14-to-5 betting favorite.

Robinson, who had struggled to make 147 throughout his championship reign, scaled a strong and comfortable 155 1/2 and would enjoy significant advantages in height (three inches) and reach (five-and-a-half inches). Conversely, LaMotta had two fights to wage: The one against Robinson and the other against the scale.

“I always had a problem with my weight ever since the beginning when I first started fighting,” LaMotta told Heller. “I should have always fought as a light heavyweight but there was no money around at that time with light heavyweights, so I had to always come down to 160 pounds. Three days after the fight, I would go up to 190 and eventually go up to 200 pounds.”

Now, at age 28 — 14 months younger than Robinson — the process of boiling down to 160 was pure torture, and no one, especially LaMotta, was sure if he would make weight until the very last minute.

“Five days before the fight, practically starving myself, I made 160 pounds,” LaMotta told Heller. “But I was so weak that I stopped training. I was in Chicago at the time. I just laid around. I had steak three times a day, no vegetables, nothing, just a piece of steak three times a day with a little cup of tea. And when I weighed myself the night before the fight I was 164 1/2. I had to lose 4 1/2 pounds. I went to the steam room and that night, all night long, in and out, in and out. Finally, I made 160 pounds that night. I was very weak. I did drink brandy before the fight to give me some strength.”

The showdown, which aired nationally on CBS, attracted a better-than-expected gate of $180,619.64 generated by 14,802 customers, many of whom were rooting for the underdog champion. A slew of boxing celebrities were brought into the ring — champions Barney Ross, Johnny Coulon, Tony Zale and Jackie Fields, future titlist Johnny Bratton, and contenders Chuck Davey, Bob Satterfield and Cesar Brion — and following the playing of the national anthem, the introductions and the final instructions, the fight was on.

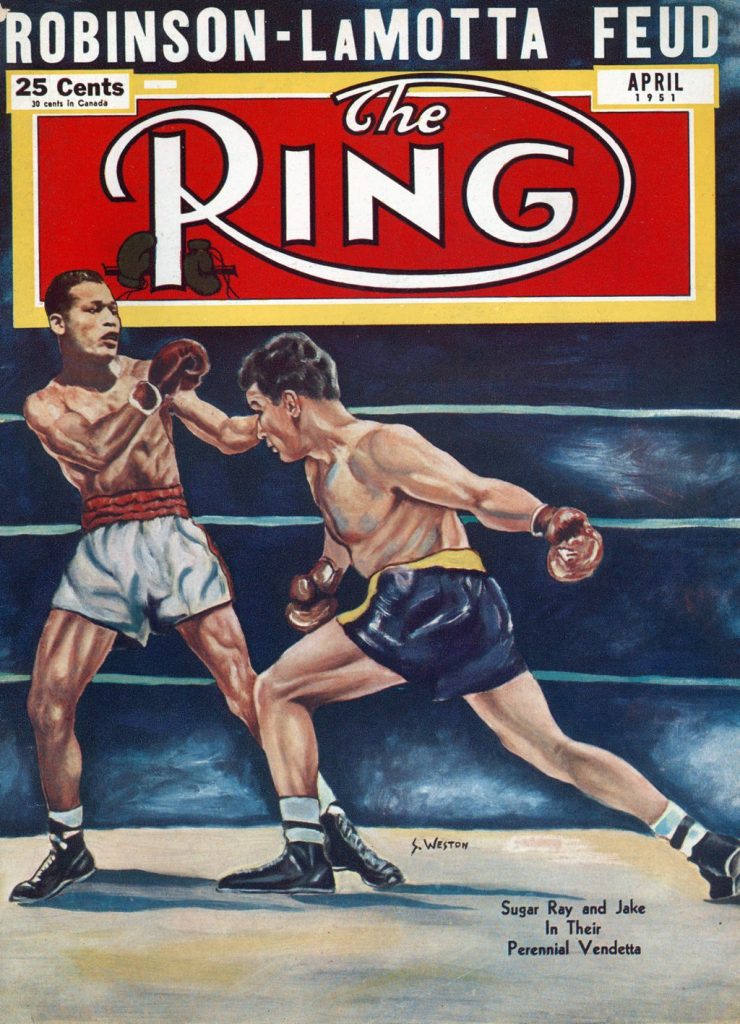

April 1951 issue

Both men commenced the combat in typical style; the tall, angular Robinson working behind a busy jab and the crouching LaMotta driving forward and looking to land hard to the body. In a little more than a minute, Robinson’s stabbing lefts had reddened LaMotta’s nose and right eye, but the champion also was getting in his licks, and he was doing so with a most unexpected weapon — the jab. Despite his reach disadvantage, LaMotta’s left connected with surprising speed, timing and fluidity, and, at times, he doubled and tripled it up. Then, just as suddenly, he returned to his customary attack, and he consistently scored with body-head volleys that got through the guard. This diversity of offense kept Robinson guessing as to what would come next, and it also helped the champion’s cause that the crowd rewarded his successes with loud cheers.

Although the first round was closely contested, it was LaMotta who succeeded in establishing a firm strategic base. If this were a chess match, Robinson used the first round to push out his pawns while LaMotta aggressively introduced his rooks, bishops and knights.

The second round was a near carbon-copy of the first, though in the final minute a Robinson power flurry forced LaMotta to take a step back. Still, it was LaMotta who forged an early lead, for it was he who initiated most of the exchanges and it was he who scored more often with more weaponry.

Knowing this, Robinson shifted into a higher gear at the start of Round 3 as he raced toward LaMotta and sprung into action with a lead right to the ear and a series of rights to the body and jaw as the champion clinched. LaMotta responded with a looping hook to the jaw that landed cleanly but Robinson answered with a right and two hooks to the body that drove LaMotta back. For the first time in the fight, Robinson fired his full array of weapons that included looping rights to the short ribs, uppercuts that snapped the champion’s head, and whistling combinations that left LaMotta briefly bedazzled. Robinson was more than willing to engage with “The Bronx Bull,” and his spearing blows earned him his first round of the match.

Robinson’s surge continued early in the fourth as he unleashed a vicious volley that drew a trickle of blood from LaMotta’s right nostril — but little else. Robinson had knocked out dozens of men with similar explosions, but he knew LaMotta was made of far sterner stuff, and that stuff required Robinson to maintain the pressure while also marshaling his resources for the long haul. A heavy right to the side of the head caused LaMotta to back away, and, by taking a deep breath while in a subsequent clinch, the champion showed the first signs of fatigue. Seeing this, Robinson, now bleeding slightly from both nostrils, invested even more power into every blow. Perhaps, over time, Jake would be ripe for the taking, but that time had not yet arrived because in the round’s final minute LaMotta landed a jolting double hook to the body and head while also continuing to connect with his pesky yet effective jabs.

The fifth saw the tide turn yet again as Robinson throttled down and LaMotta geared up. His accurate jabs carried even more snap and they helped set up a piercing right to the chin that brought a roar from the army of LaMotta partisans. Although Robinson continued to stick and move, LaMotta continually found holes in the challenger’s defense and exploited them all. While they weren’t hurting the welterweight champion, they were scoring points — and winning rounds.

LaMotta consolidated his fifth-round success with an even better sixth as he increased the pressure and raked Robinson with hooks, body punches and rhythm-destroying jabs. Meanwhile, his rolling upper body avoided many of Robinson’s replies, and those punches that did land had little effect on the thicker, sturdier man.

LaMotta’s surge continued through the seventh and eighth, and at the halfway point the middleweight champion appeared to be in control of the contest. United Press International reporter Jack Cuddy had LaMotta ahead six rounds to two, and a count conducted by CompuBox decades later corroborated that scoring, for LaMotta out-landed Robinson in terms of total punches in six of the first eight rounds while also creating connect leads of 226-205 overall and 112-82 power. Incredibly, LaMotta trailed Robinson by only 123-114 in terms of landed jabs and each man found plenty of gaps in the other’s guard as Robinson landed 36% of his overall punches, 29% of his jabs and 57% of his power shots to this point compared to LaMotta’s 41% overall, 34% jabs and 53% power. The statistics also confirm that while both landed more than half of their power punches, this was mostly a boxing match as jabs comprised 74.6% of Robinson’s total output and 61.2% of LaMotta’s — well above the 42% middleweight average. And, to the amazement of most, LaMotta not only was out-brawling Robinson, he was out-boxing him.

But after a round in which LaMotta uncorked a fight-high 100 punches to Robinson’s 82, the effects of LaMotta’s weight-cutting ordeal were about to catch up with him.

Photo from The Ring archive

At first, those effects were mild. LaMotta’s animated upper body movement was stilled and he didn’t project as much energy as was the case in rounds five through eight. As Round 9 moved into its final minute, Robinson threw a right uppercut to the pit of LaMotta’s stomach that was followed by a cluster of power shots. Another right to the body set up a teeth-rattling hook to the jaw, and, after a brief salvo by LaMotta, Robinson ended the round with a short hook, a pair of right uppercuts and a six-punch burst highlighted by a looping right to the short ribs and a hook to the jaw. It was Robinson’s best round since the fourth, and, unfortunately for LaMotta, more was to come. Much more.

Upon leaving his stool to start the 10th, Robinson looked sprightly and revitalized while LaMotta stood in his corner, then walked in small circles as if he were gathering his thoughts and steeling himself for the final drive. A six-punch body-head bouquet rattled LaMotta, who lacked the energy to do anything else but roll away from as much incoming as he could and poke out jabs whenever possible. It was Robinson who began and ended every exchange, and LaMotta’s lack of response enabled the welterweight champion to fire at will, especially with right uppercuts to the belly and short neck-wrenching hooks. Robinson, who threw 85 punches in the ninth, fired another 85 in the 10th while LaMotta’s output slumped from 57 in the ninth to 38 in the 10th.

Though his reserves were running low entering the 11th, LaMotta decided to roll the dice one last time in the hope that he would hurt, if not stop, Robinson and save his championship. Thanks to his miraculous TKO over Dauthuille, LaMotta had good reason to believe he could pull another rabbit out of the hat. Forty-five seconds into the round LaMotta had maneuvered Robinson toward his corner with a series of blows, and when the challenger appeared to briefly lose his footing while ducking under a right hand, LaMotta smartly chose that moment to pounce. Over the next 15 seconds LaMotta unleashed 25 punches , and several — including a hook to the body, an overhand right to the jaw and a pair of 45-degree left hooks to the chin — connected forcefully. But Robinson rode out the storm, fought off LaMotta with an eight-punch salvo, then forced a clinch. The weary look on LaMotta’s face indicated that he had shot his final bolt, and because he came up empty it opened the door to the bout’s brutal culminating act — the act that led to this bout being remembered as a massacre.

It began with a knifing right to the ribs that stopped LaMotta in his tracks and it continued with an explosive right cross-left uppercut-right cross that knocked the champion off balance followed by a double hook-right cross along the ropes. A scorching right to the body caused LaMotta to curl up, which, in turn, ignited yet another Robinson combination that connected cleanly. It was now obvious that Robinson was gunning for the knockout, and LaMotta scarcely had the fuel to even try to block anything that came his way, even jabs. A whistling hook drove LaMotta to one set of strands while a triple hook caused LaMotta to totter toward another set of ropes. A right uppercut-double hook nearly took Jake off his feet and a final hook to the face ended one of the most harrowing rounds of LaMotta’s professional career.

As bad as the final half of Round 11 was, the entirety of Round 12 was even worse.

Photo from The Ring archive

From first second to last, the undisputed welterweight champion sought to become the first man to knock LaMotta off his feet. He used jabs to line up the target for his beautifully delivered combinations, most of which struck their intended targets. For LaMotta, the objective no longer was to keep his championship but to preserve the record for which he invested so much pride: Keeping his feet — no matter what.

With his left eye swelling, his chest heaving and his visage wincing, LaMotta remained defiant in the face of ceaseless punishment. This once-competitive fight — a fight that previously had been controlled by LaMotta — had been transformed into a display that tested Robinson’s killer instinct, LaMotta’s desire for self-preservation and referee Frank Sikora’s humanity.

During the final minute of Round 12, CBS commentator Jack Drees declared that “no man can endure his pummeling,” but endure LaMotta did. Robinson took on the look of a lumberjack chopping away at the world’s thickest sequoia; the tree could do nothing to stop the blade from cutting into it, but its sheer mass could render its attacker so exhausted that the job could not be completed.

The statistics further illustrated the savagery of Robinson’s assault: He landed 57 of his 92 total punches (62%), 11 of his 33 jabs (33%) and 46 of his 59 power punches (78%). LaMotta responded with only 12 total punches, of which two landed.

Between rounds 12 and 13, all the attention was focused on LaMotta’s corner. His corner men worked feverishly over him while a pair of physicians sought to determine whether he was fit to continue. Under today’s standards, that would be an open question but in 1951, a champion — especially one armed with LaMotta’s warrior spirit — had the right to go out on his shield if he so chose.

LaMotta unhesitatingly rose from his stool to face Round 13 and a Robinson eager to empty every bullet from every chamber. For him, LaMotta was an absurdly easy target to strike but an impossible one to knock off its moorings.

Shortly before the end, Robinson backed toward ring center, set his feet and inched forward toward LaMotta to ascertain the perfect spot, identify the perfect angle, and position himself to generate maximum leverage. As Robinson did so, LaMotta, despite knowing what was coming, still stepped toward his executioner and waited for the final receipt to be delivered.

That receipt was a blowtorch right cross that connected with full flushness. His head corkscrewed dangerously and though he fell into the ropes his legs were still underneath him. Robinson then fired a combination that included a pair of hooks and a right uppercut before Sikora finally stepped between the fighters and called off the slaughter. At fight’s end, LaMotta bled from a deep gash on his left cheek as well as minor cuts on his nose and mouth.

Photo from The Ring archive

Robinson’s finishing flourish was brutally aesthetic as well as statistically breathtaking. He landed 48 of his 67 total punches (72%), 19 of his 29 jabs (66%) and 29 of his 38 power punches (76%) while LaMotta mustered 12 total punches, landing four, and conjuring four power shots, connecting on one. In the final two rounds alone, Robinson out-landed LaMotta 105-6 overall, 30-4 jabs and 75-2 power, margins that extended his final leads to 442-290 overall, 198-137 jabs and 244-153 power in what was a high-contact fight for both (Robinson led 44%-40% overall, 31.8%-31.7% jabs and 64%-51% power).

Robinson was well ahead on all scorecards at the time of the stoppage as referee Sikora had him up 63-57 while judge Frank McAdam favored him 65-55 and judge Ed Klein’s 70-50 total was identical to that of The Ring Magazine founder, Nat Fleischer.

Despite the decisive defeat, LaMotta remained the people’s choice. As the former champion left the ring, the Chicago crowd, accompanied by the house organist, serenaded him with a rendition of “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow.” But the beating he absorbed was so severe that Dr. Houston administered oxygen to LaMotta in his dressing room and he was not made available to the media for two hours.

Thanks to an agreement between Robinson, the Illinois Boxing Commission and the National Boxing Association (the forerunner of the World Boxing Association), the world welterweight title instantly became vacant.

With the victory, Robinson became the first reigning undisputed welterweight champion to dethrone the world middleweight champion, and, in doing so, he injected new energy into three weight classes. According to Fleischer’s editorial in the April 1951 issue, Robinson’s departure at welterweight created the need for a tournament to crown a new champion while also making real a slew of attractive matches at 160. Robinson, however, had his eye firmly locked on a fight with undisputed light heavyweight champion Joey Maxim because, if victorious, he would join Bob Fitzsimmons, Tony Canzoneri, Henry Armstrong and Barney Ross as boxing’s only triple-crown champions. And with LaMotta moving up to 175, a seventh meeting with Robinson could have been in the offing.

Although Robinson’s victory is now 70 years into the past, most historians still regard him as the greatest boxer, inch-for-inch and pound-for-pound, that ever put on gloves. But on this Valentine Day’s night, Jake LaMotta displayed in abundance a most appropriate asset — heart.

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, West Virginia. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 19 writing awards, including two first-place awards, since 2011. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. He is the author of “Tales from the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics” (available on Amazon) and the co-author of “Muhammad Ali: By the Numbers” (also available on Amazon). To contact Groves about a personalized autographed copy, use the email [email protected] or send him a message via Facebook.

SUBSCRIBE NOW (CLICK HERE - JUST $1.99 PER MONTH) TO READ THE LATEST ISSUE