Carmen Basilio-Sugar Ray Robinson 2: Warfare never to be seen again

A lot has happened in boxing over the past 63 years. Much change has been initiated. Where once there were eight classic weight divisions with one universally accepted world champion in each, there are now 17 divisions, with four self-important “major” sanctioning bodies asserting that their alphabetized titleholders are the true claimants to such a designation. Some of today’s champs, particularly elite ones, get paid much more to fight far less often than their predecessors. Enhanced safety standards have led to the abolishment of 15-round title bouts with 12-rounders now in their stead, and bouts in which a particular fighter is deemed to be absorbing too much punishment are stopped much more quickly than had been the case in past generations.

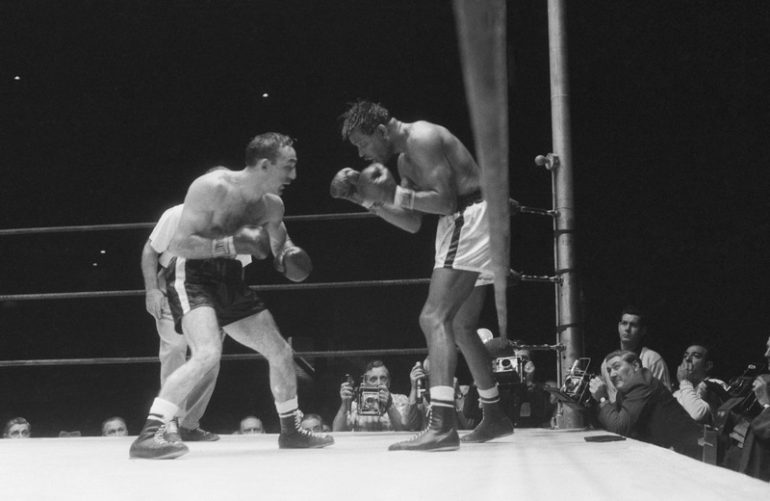

In light of those developments, what happened the night of March 25, 1958, in Chicago Stadium is a prime example of what used to be but no longer is, a historically significant event perhaps beyond replication. The legendary Sugar Ray Robinson’s 15-round split decision win over defending middleweight ruler Carmen Basilio elevated him to dominion over the 160-pound weight class for the fifth time, a record that now seems as unreachable to current practitioners of the pugilistic arts as is Archie Moore’s long-standing and incredible stockpile of 132 knockout victories.

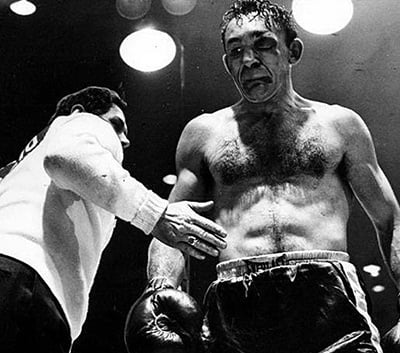

Perhaps as notable as the original Sugar Ray’s cha-cha of bejeweled middleweight belts won and lost or relinquished was the sight of the valiant Basilio in his first and only defense of that title. Fighting from the sixth round on with a massive, purplish hematoma on his totally closed left eye, the undersized “Upstate Onion Farmer,” the inspiration for the establishment of the International Boxing Hall of Fame in his hometown of Canastota, New York, went toe-to-toe with Robinson for nine-plus rounds with his vision severely restricted by something that resembled a rotting eggplant.

November 1957 issue

Robinson and Basilio had set the stage for what was justifiably named The Ring’s 1958 Fight of the Year by engaging in a virtually identical blood-and-guts showdown six months earlier in Yankee Stadium. Basilio, the reigning welterweight champion, had lifted Sugar Ray’s crown on, natch, another 15-round split decision that was fraught with excitement and two-way action. That fight, which took place on September 23, 1957, also was anointed as The Ring’s Fight of the Year. But if Robinson’s collection of five undisputed middleweight championships seems remarkable, and it does, consider this: action hero Basilio was a participant in The Bible of Boxing’s FOY for five years inclusive, from 1955 through ’59, the others being knockouts of Tony DeMarco (1955) and Johnny Saxton (1956) in rematches, and a knockout loss to Gene Fullmer (1959) in the first of their two matchups.

In legend and lore, Jake LaMotta is often recited as Robinson’s most memorable opponent, but that largely owes to the fact they squared off six times, so frequently that Jake liked to quip that “I fought Sugar Ray so often it’s a wonder I don’t have diabetes.” But had there been a rubber match involving Robinson and Basilio, and particularly if it was another thrill-fest as were the first two meetings, that arch-rivalry in triplicate might now rank alongside the Holy Trinity of boxing that is Muhammad Ali vs. Joe Frazier.

“He wouldn’t give me a rematch. He knew I won,” Basilio, who was 85 when he died on November 7, 2012, frequently complained, the inference being that Sugar Ray had had much of what remained of his ring sweetness drained from him by the punishment he had taken over 30 rounds of intense combat with a relentless, undiscouraged attacker who, in a manner of speaking, played the role of an early Smokin’ Joe to Robinson’s Ali. It is not an unreasonable premise; two hours after he had his hand raised in victory, a dog-tired and well-pummeled Robinson had to be assisted to bed in his Chicago hotel suite.

“Even the soles of my feet hurt,” the man who arguably is the greatest prizefighter ever to lace up a pair of padded gloves said in a voice barely above a whisper.

And just as the defeated but defiant Frazier had boasted after the “Thrilla in Manila” ended with Joe’s compassionate trainer, Eddie Futch, not allowing his nearly blinded fighter to come out for the 15th round against an equally battered Ali, Basilio, his grotesquely swollen left eye notwithstanding, said, “I walked out under my own power. They had to carry (Robinson) out.”

Truth be told, the epic nature of the two Robinson-Basilio confrontations might have owed to the extremely high mileage on both fighters’ professional odometers, and particularly that of Sugar Ray, who was 36 when he went into the rematch with Carmen with a 140-6-2 record in a pro career launched in 1939. As impressive as that mark was, it is generally accepted that the man whose birth name was Walker Smith Jr. was always more spectacular as a welterweight than he was as a middleweight. Before he began dropping hints that he was merely mortal, after he returned to boxing after a three-year European sojourn as a song-and-dance man, Robinson had been 123-1-2. Among boxing immortals atop Mount Olympus, Sugar Ray reigned long as Zeus. But even gods of the ring are as susceptible to the natural laws of diminishing returns as the rest of us, and Robinson went into battle an almost incomprehensible 13 times in 1949, although his welterweight title was on the line only once during that span.

Robinson’s slide from on high to a place where indisputable greatness has been replaced by something less magnificent was never more evident than the night of January 19, 1955, when he dropped a shockingly one-sided, 10-round decision to capable gatekeeper Ralph “Tiger” Jones, also in Chicago Stadium. Writing in the New York Journal American, noted sports columnist Jimmy Cannon authored what he believed was Sugar Ray’s pugilistic obituary. “There is a language spoken on the face of the earth in which you can be kind when you tell a man he is old and should stop pretending he is young,” Cannon wrote. “Old fighters, who go beyond the limits of their age, resent it when you tell them they’re through … what he had is gone. The pride isn’t. The gameness isn’t. The insolent faith in himself is still there … but the pride and the gameness and that insolent faith get in the way. He was marvelous, but he isn’t anymore.”

May 1958 issue

Cannon’s epitaph for Robinson proved a bit premature. After the stinker vs. Jones, a rebounding Robinson won the middleweight title against Bobo Olson, lost it to Gene Fullmer, won it back from Fullmer on that picture-perfect left hook, lost it again to Basilio. For the grudge rematch – Basilio was respectful of Robinson the fighter, but openly resentful toward his haughty attitude toward upcoming opponents in contract negotiations – the new champ went off as an 8-5 favorite and was the pick of 21 of 34 on-site fight writers, despite the challenger’s obvious physical advantages. Robinson was 5’11” to Basilio’s 5’6½”, weighed in at 159¾ to Basilio’s 153½ and had a 72-inch reach. Basilio’s reach was not announced or recorded, but most estimates pegged it at three or four inches shy of Robinson’s.

Some of the media on hand to chronicle the event dusted off the Sugar Ray-is-done theme forwarded by Cannon two years earlier. Bill Lee, sports editor of the Hartford Courant, opined that “Robinson should have been washed up six or eight years ago. His speed is gone and perhaps his durability has died with the speed.”

Nor was the Chicago Tribune’s Bill Strickler impressed by what he had seen of Robinson after his narrow escape against Basilio, who might as well have fought with pirate’s eyepatch covering his grotesquely swollen left eye. In his post-fight report, Strickler wrote that the very best of Sugar Ray “is gone. The Robinson of today is just a good fighter, who flopped on his stool between rounds, arm weary and gasping, then had to be helped to his dressing room.

“From the opening round to the end, and especially thru (sic) the late stretches when Basilio got no rest between rounds as his seconds plied him with ice packs and medicines, Robinson resembled a man looking for something he could not find.”

Whether those harsh assessments of Robinson’s then-status were valid or not hardly seems the issue. He and the wounded Basilio had nonetheless again made magic inside the ropes, perhaps in part because they both had settled onto a more or less similar competitive plane, perhaps because what Basilio had elected to endure rose to the level of near-superhuman endurance.

Basilio was 64 when he recalled the fourth-round punch that almost instantly begun to close the eye, which was completely shut by Round 6. “(Robinson) had a vicious uppercut,” he said. “He threw that f—— punch five times. I blocked the first four but the fifth one got through. It cut a blood vessel and my eyelid just blew up. My (co-)manager, Joe Netro, wanted to stop the fight. I told him, `You stop this fight and you better not be in town when I get out of the ring.’”

Was the eye as agonizing as it must have appeared to be to the 17,976 in-house spectators, a CBS television audience and 350,000 or so purchasers of tickets to the closed-circuit telecasts at 114 sites around the United States and Canada?

“I was in excruciating pain,” Basilio confirmed. “I slept with an ice bag on it for two days. But it was OK. Right now I can see great out of this eye.”

Carmen Basilio, between rounds of his fight-of-the-year rematch with Sugar Ray Robinson, is the epitome of the blood-and-guts warrior.

Basilio’s corner team – trainer Angelo Dundee and co-managers Netro and Johnny De John – were criticized for allowing their guy to fight on in such a distressed condition, but Dundee’s decision not to lance the blood-gorged area between the fifth and sixth rounds with a sterile razor blade he had brought for just such a purpose might have proved a saving grace. Several days after the fight, Dr. Richard A. Perritt, an eye specialist at Wesley Memorial Hospital in Chicago, examined Basilio’s left eye after the swelling had gone down. He determined that the lancing of the hematoma might have resulted in infection of veins leading to Carmen’s brain, with cerebral thrombosis and permanent eye damage as possible results.

Although judges Spike McAdams (72-64) and John Bray (71-64) saw Robinson as the winner by fairly wide margins using the five-point must system then in effect, referee Frank Sikora had it 69-66 for Basilio, which might have been closer to the truth. Basilio-Robinson II was a close fight, and a terrific one, and something that never could happen now.

For a story I did on the first pairing of then-heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson and Swedish challenger Ingemar Johansson, which took place on June 26, 1959, in Yankee Stadium, Dr. Margaret Goodman – the Las Vegas-based neurologist and former chief ringside physician for the Nevada State Athletic Commission – pointed out that Ingo’s seven floorings of Patterson, all in the third round, are a relic from an era that has passed into history and isn’t coming around again.

“Seven knockdowns in one round are obviously excessive,” she stressed. “Thank goodness times have changed. The standard for the way things were handled back then were different. There was a greater likelihood of allowing a fighter to continue taking that kind of punishment. How horrible is that?”

Basilio’s display of agonizing one-eyed courage, like Patterson’s going to the canvas seven times in the same round, are just two examples of boxing’s evolution from its shadowy past into a more sanitized version of itself. So, too, is the likelihood that the powers that be would have denied the great Sugar Ray Robinson – who kept on keeping on until November 10, 1965, when he dropped a one-sided UD10 to Joey Archer in Pittsburgh – authorized approval to do so after it long since had become apparent that he was a shell of his former self, and not only physically. The king of the ring was just 67 when he breathed his last on April 12, 1989. By then the accumulated effect of 200 professional bouts (174-19-6, with one no-decision), not to mention 89 more as an amateur, had contributed to his being confined to a wheelchair, unable to recall details of his career or to recognize the faces of loved ones.

It is right and proper to celebrate what the fight game has gained in its inexorable march of progress, but it is also right to bemoan at least some of what has been lost. Robinson-Basilio II is just such a time-capsule heirloom.

READ THE LATEST ISSUE OF THE RING FOR FREE VIA THE NEW APP NOW. SUBSCRIBE NOW TO ACCESS MORE THAN 10 YEARS OF BACK ISSUES.