FOR 97 OF ITS 100 YEARS, THE RING HAS RANKED THE TOP FIGHTERS IN THE GAME – HERE, THROUGH THE LENS OF THOSE LISTS, WE LOOK BACK AT THE 100 MEN WHO PERSONIFIED THE PHRASE “TO BE THE BEST, YOU HAVE TO BEAT THE BEST”

This is not a ranking of the 100 best fighters in a century of The Ring Magazine.

Plenty will read it that way, skimming right past this and diving in to let the debates begin. Most of the fighters one would expect to see on such a list are here, so a little misunderstanding is inevitable.

For those who take a moment to understand what this is, versus what it’s not, there should be plenty to enjoy and it will alleviate some reader anxiety (No Sandy Saddler?! Where is George Foreman?!). This is a study of fighter performance using The Ring’s ratings – from the divisional rankings’ debut within the pages of the February 1925 issue to today – as the central gauge.

Tex Rickard was a pioneer in terms of boxing promotion and orchestrated the first million-dollar gate.

Several years ago, research began on a project for The Ring’s centennial. The idea was to treat the rankings almost like seeds in a never-ending tournament. On the occasion of The Ring’s 100th birthday, what can those rankings tell us about who beat whom and when they beat them?

The Ring has published top 10 divisional rankings for 97 years. Using a formula focused on where an opponent was ranked in the print issue prior to a specific fight, and based on official outcomes, these are the top 100 fighters calculated by their performances vs. Ring-rated opposition.

Let’s start at the beginning.

While honorary Ring Magazine championship belts have been around since 1922, the idea of ranking the best of each weight class didn’t come to fruition until the February 1925 issue. The header read, “Boxers of the World Ranked in 1924 by ‘Tex’ Rickard,” with the sub-header “Famous Promoter Issues First List of Its Kind – Gives Dempsey and Leonard Only Complimentary Rating.”

Editor Nat Fleischer introduced the rankings in nine divisions, writing, “It is the privilege of The Ring to present to the boxing followers of the world ‘Tex’ Rickard’s ranking of ring performers for the year. Coming from the leading promoter in the sport and the impresario at Madison Square Garden in New York, the tabulation and the accompanying article are of unusual importance and vital interest. It is the intention of Mr. Rickard to make the ranking an annual feature … on a relative parity with Walter Camp’s All America team.”

Annual ratings would appear in The Ring’s February issue until moving to the March issue in 1965. The final annual appeared in the May 1987 edition. Contributor Eddie Borden added monthly rankings for the first time in the March 1928 edition, writing, “The publisher has decided to devote one page each month … to a rating of the ten leading boxers in each division for that month. In the rating, which will be in charge of the writer, the champion will be listed first in deference to his position.”

February 1925

Borden’s first monthly rankings consisted of 10 weight classes. The October 1929 issue separated champions from the top 10 for the first time. Every February issue until 1942 included an additional “annual” list, which then became the only rankings to appear in the year-end issue (which eventually moved to March) until 1981. After that, the annual issue again included both lists.

Under new management, The Ring opted to drop the “champion” designation and rate just 10 fighters in each division in the January 1990 issue. Editor-in-chief Steve Farhood provided the rationale in the May 1990 issue’s Ringside column. “In a perfect boxing world, there would be one champion per division. But there isn’t one champion per division, and whether you accept the WBC, WBA, and IBF, or dismiss them as self-serving sanctioning bodies, the question of who deserves to be the real champion, and who doesn’t, are no longer simple ones.” Farhood later added the philosophy going forward would be focused on “Who is the better fighter. What’s the point of rating one fighter the world champion if he’s not the best in the division?”

The classic standard returned in the April 2002 edition. Editor-in-chief Nigel Collins wrote, “This new policy is not intended to discount the accomplishments of the alphabet titlists, many of whom are outstanding fighters. It is, rather, a way to differentiate between a fighter who holds a ‘title’ and an authentic world champion.” A notable change since Collins’ championship policy reinstatement are rules in place to allow The Ring to remove championship recognition under specific circumstances.

Currently, The Ring recognizes 17 weight classes. Heavyweight, light heavyweight, middleweight, welterweight, lightweight, featherweight, bantamweight and flyweight have been in every set of rankings since February 1925. The years for the others are:

- Cruiserweight (April 1984-June 1987; January 1990-present)

- Super middleweight (January 1990-present)

- Junior middleweight (December 1974-June 1987; January 1990-present)

- Junior welterweight (February 1928-October 1932; September 1962-June 1987; January 1990-present)

- Junior lightweight (February 1925-October 1932; September 1962-June 1987; January 1990-present)

- Junior featherweight (May 1979-June 1987; January 1990-present)

- Junior bantamweight (January 1990-present)

- Junior flyweight (September 1991-present)

- Strawweight (January 1999-present)

The first task in evaluating a century of rankings was assembling all of them. Thanks go to the International Boxing Research Organization, especially Gary Luscombe for his assistance on several issues from the 1920s and early 1930s. Thanks also to all who maintain records on BoxRec.com, the primary source for fighter information. Rankings were compiled in a database through the January 2022 edition and fight results are current to November 6, 2021.

Fighters who won a Ring championship (which, historians will note, usually but not always lines up with historical lineage) or primary NBA/WBA, WBC, IBF or WBO titles were identified along with every inductee to the International Boxing Hall of Fame and the defunct Ring and World Boxing halls of fame, plus everyone currently on the IBHOF ballot through October 2021, generating a pool of over 1,400 fighters to evaluate. Fifty-seven were removed in the final evaluation, having never achieved a top 10 Ring ranking and/or a result against a Ring-rated fighter.

Early on, a sample comparing some fighters from older, higher-activity eras and recent top names was used to test the points method applied. If there was no way to reasonably compare a Tony Canzoneri to a Manny Pacquiao, the approach taken might have been quite different. The final results here illustrate that a comparison can be made with a cross section of every generation of The Ring’s long history.

This is not a review of full careers, though career records are supplied for purposes of comparison. The study was scaled from a fighter’s first to last appearance in The Ring’s divisional rankings. All relevant results correlating to those dates/issues were fair game. Results outside those dates were not. Typically, The Ring’s monthly rankings carry an “as of” date roughly two to six months behind the cover date. Those dates helped to ensure accuracy against the date of fights.

Interested readers can find details about the points formula used to evaluate the fighters in this top 100 after the rankings. The essentials are:

- Points for wins and losses derived from a base 11-point scale.

- Points for wins and losses were tracked and ranked two ways:

- Overall total points

- Peak points (the highest point a score ever reached)

- Note: Wins and losses to opponents in higher and lower divisions were included with an adjustment.

- Total wins against ranked opponents between a fighter’s first and last Ring ranking were tracked as a separate category. Fighters were ranked against each other there as well.

All divisional top tens and eras were treated equally. An obvious argument is not all champions or number-one contenders are equal. The study doesn’t make any qualitative distinction. Scores are based on the rankings and results alone, using the principle that no one can fight beyond the top tens of their time. This study reflects success relative to era.

The “No Decision” era in boxing provided some storied contests without official verdicts. No points were awarded even where prominent unofficial “newspaper decisions” are available. Those fights, when against ranked opponents, are included. Study results are based only on official outcomes.

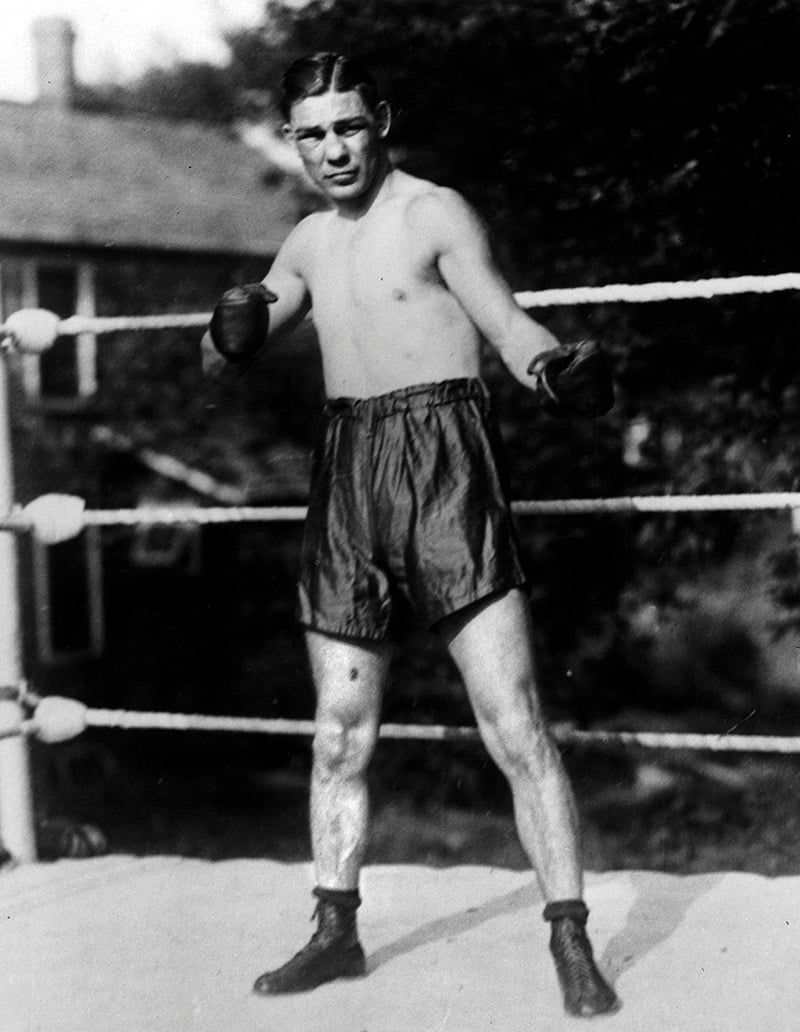

A prime version of middleweight and pound-for-pound all-time great Harry Greb in 1925.

Official outcomes also meant accepting historically reviled decisions and the rankings during the era when associate editor John Ort was accused of bribe-related rankings manipulation in relation to the United States boxing championship tournament in the 1970s. No attempt is made to relitigate or editorialize results, though many controversies are described.

The Ring rankings throughout their history weren’t perfect or always correct. They are, though, by and large, a strong snapshot of what was happening in the squared circle in their time.

There was one major cheat applied. For a period between 1987 and 1989, Ring ceased recognition of five weight divisions. KO Magazine was used as a supplement to better capture the full breadth of those two years, particularly in the “junior” weight classes. Ring rankings remained the first option.

Why apply a supplement? The decision to cease recognition of junior welterweight and junior lightweight in 1932 reflected the reality of the sport at the time. While nobly intended, the decision in 1987 to recognize only the “original eight” weight classes did not. Even The Ring’s debut rankings in 1925 featured nine weight classes. Over 97 years of Ring rankings, original-eight exclusive rankings were the norm for only approximately 32 years.

Why KO and not other prominent publications? In 1989, Stanley Weston purchased The Ring and added it to a body of magazines that then included KO most prominently. The rankings in the January 1989 issues of The Ring and KO largely mirror each other, though KO ranked a top 12 in each weight class versus just 10 in The Ring with some differences in editorial management. It was close enough to an organic transition for use here.

Another small cheat, used sparingly, was for occasions where a loss to an unranked fighter was based purely on a policy technicality. The third fight between Jimmy McLarnin and Barney Ross is an example.

Some big names are missing or fragmented. Jack Dempsey and Benny Leonard led their classes in 1925, but their active careers were nearly over. The study is focused only on the years when The Ring ranked fighters and those two didn’t have enough quality activity from 1924 forward. Only the last two years of Harry Greb’s career could be scored; he still made the top 100.

Mexican strawweight great Ricardo Lopez missed the cut by no fault of his own. (Photo by Al Bello/Allsport)

Others just didn’t perform well enough against the rankings or have enough results. Ricardo Lopez was a staple of The Ring’s pound-for-pound top 10 throughout the 1990s, but strawweight wasn’t included in the magazine until 1999. Earlier years of The Ring combined divisions like junior middleweight and middleweight when The Ring didn’t rank the lighter class separately. That also affects outcomes but at least creates scoring options. The Ring did not combine strawweight and junior flyweight in the 1990s, so most of Lopez’s career wasn’t scorable.

A study of this size will inevitably miss something along the way, but every effort was made to ensure complete and accurate results for this top 100.

The legend for the scoring results section is: Opponent and result – (opponent ranking) – opponent weight class – Cover date for the issue with the opponent’s ranking. The use of +/- next to some opponent rankings denotes the opponent was ranked above or below the weight class of the fighter being examined in that issue. Two + signs would mean they were facing someone two weight classes up based on how many divisions The Ring ranked at the time. An asterisk is used to note a Ring championship title change or a vacancy being filled.

Again, this is not a ranking of the 100 best fighters in The Ring Magazine’s history.

It is a celebration of those who took the time to try to make sense of the sometimes chaotic world of boxing, month after month, for all these years.

Happy birthday, Ring Magazine. Here’s to 100 more.

THE RANKINGS

26-100

(plus detailed scoring description)