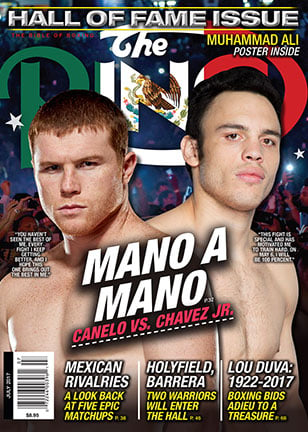

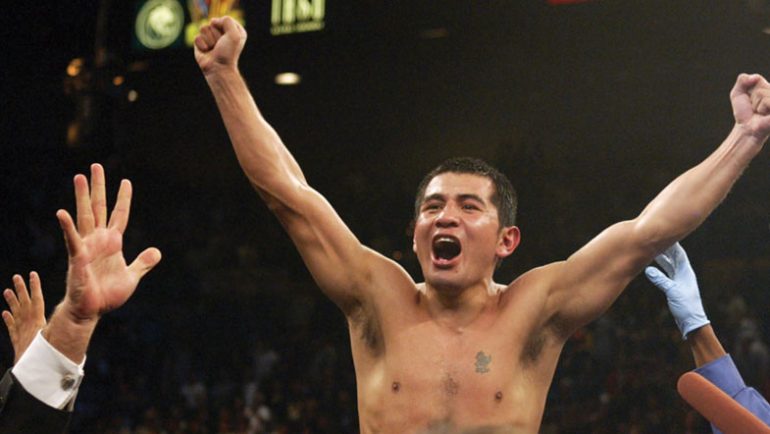

Marco Antonio Barrera

The Unlikely Icon: Writing Off The Resilient Marco Antonio Barrera Was Never A Good Idea

Marco Antonio Barrera is proof that you can fall short of initial expectations, lose a bunch of fights and change your style to one that is actually less fanfriendly than the one that made you a star in the first place, yet still find yourself inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame. Granted, we wouldn’t advise other fighters to follow the same route, but in Barrera’s case it worked out.

Barrera fought his way into the spotlight when all of Mexico was awaiting their next hero. The reigning icon, Julio Cesar Chavez, was still going strong in 1989 when Barrera, a 15-year-old flyweight from Mexico City – fighting with falsified papers because he was too young to box for pay – earned his first professional victory, a two-round TKO over another novice named David Felix. By 1996, when Barrera scored his 40th victory by stopping Kennedy McKinney in an unforgettable fight on a new HBO show called “Boxing After Dark,” Chavez was at the beginning of his career downturn. Boxing got lucky with Barrera. Just as Chavez was fading, it looked as if another Mexican-born slugger was on deck to take his place.

Of course, there were differences. Chavez was a party guy with a big smile, while Barrera was serious. Chavez was passionate and liked to spill some blood. Barrera was a thinker in the ring, earning a nickname that ranks among the best in boxing annals: “The Baby-Faced Assassin.” Barrera was lighter on his feet than Chavez and had a prettier style, but he banged with his left hook in a way that harkened back to great Mexican fighters like Ruben Olivares. Erik Morales, who was never quick to compliment Barrera, said after their bruising first bout, “He was the biggest puncher I ever faced in the ring.”

However, the same year as his star-making victory over McKinney, Barrera lost a shocker to Junior Jones. He lost the rematch, too. Then, admittedly depressed, he temporarily retired from the business. It turned out he wasn’t the new Chavez, after all. It took the boxing world a while to figure out exactly where Barrera fit in the scheme of things.

“Calling him the next Chavez was a bit unfair, I think,” said former HBO Boxing commentator Larry Merchant, who was on the broadcast of many Barrera bouts. “He looked like the successor to Chavez, the next in line to win the hearts and minds of the Mexican fans, but Barrera lost some fights, so there went the distinction. Chavez appeared imperially unbeatable, and was such a pure representation of the Mexican fighting heritage that to compare any young fighter to him is unfair.”

It turned out that losing some fights made Barrera even more fascinating, as watching him rise from the ashes time and again became one of boxing’s great joys. Many dismissed him after the losses to Jones, but he returned to win 14 of his next 16, transforming himself into a boxer instead of a brawler, leaving the ugliness of the trenches to snipe from the hills. The change in Barrera, and his ability to still brawl if necessary, inspired Hall of Fame trainer Emanuel Steward to call him “the most adaptable fighter in modern times.”

Barrera was dismissed again after Manny Pacquiao whipped him in 2003 at the Alamodome in Houston. We should’ve known better, for he’d notch another six victories, as well as THE RING’s Comeback of the Year award in 2004, plus a 2½-year term as WBC junior lightweight titleholder. When it was learned that an operation to alleviate headaches had left him with a small metal plate in his forehead, it was suggested that he retire. He didn’t; he kept winning. Even when he was past his prime and lost by technical decision to a younger and naturally bigger Amir Khan, he still came back and won two more bouts. Barrera’s final tally was 67-7 (44 knockouts).

He accumulated titles at junior featherweight, featherweight and junior lightweight. THE RING recognized him as featherweight champion from June 2002 to November 2003, and his record in title bouts was 23-5 (14 knockouts). Still, Barrera sometimes gave off an indifferent vibe to the whole title-belt rigmarole. And so it is with our memories of Barrera; we don’t really associate him with belts or title defenses. We remember his excellence in the ring. And we remember him as a key part of an era, perhaps the most important era in recent boxing history.

“When the tectonic plates of boxing shifted from New York to the West Coast and to Mexico, Barrera was part of a major change that overtook the sport,” Merchant told THE RING. “Think of the great smaller fighters at the time; the majority were Mexican, or Mexican-American. This was part of, if not the start of the globalization of boxing. American fans that had previously shown no interest in fighters who were not American were suddenly watching and enjoying fighters like Barrera, and Morales, and Ricardo Lopez, and (Juan Manuel) Marquez and others on a very long list. The smaller fighters replaced the heavyweights. There was something sincere about them. It was prizefighting the way it was supposed to be, with the fighters leaving it all in the ring. These were spirited kids with good stories, interesting pasts and great styles. And HBO was paying big bucks for these fights, not like Tyson money, but for the smaller fighters, it was big money.

“It was a golden era, an indelible period. I can’t remember the featherweight division ever being so good. There were at least a dozen excellent featherweights all competing at the same time. You couldn’t have made it up. Barrera fought, and beat, most of them. There were fighters like Prince (Naseem) Hamed of England: brash, thrilling, an attraction. When Barrera fought Hamed, there was a feeling that Barrera was defending the faith of smaller fighters on both sides of the border.”

Barrera turned Hamed inside-out that night in Las Vegas in 2001. As Franz Lidz of Sports Illustrated put it, Barrera “conducted a masterly boxing clinic that left the Englishman looking as off-balance as a one-legged man in an arse-kicking contest.”

Barrera capped his performance in the final round by shoving Hamed headfirst into the padded turnbuckle. Barrera could be as dirty as anybody, and had a temper to boot. Remember, he actually slugged McKinney at a press conference, and there were times he and Morales couldn’t be within 10 feet of each other without some pushing and shoving. In fact, one of the best punches of his career was thrown in his second bout with Pacquiao when referee Tony Weeks stepped in to separate the fighters. Seeing the opportunity, Barrera hit Pacquiao on the break and nearly dropped him. Barrera had a point deducted and lost a rather lopsided decision, but he sent Pacquiao back to the Philippines with something to remember him by. Granted, the punch probably came from Barrera’s frustration at not being able to solve Pacquiao’s style, but such antics didn’t keep his admirers from praising him as a gentleman.

“He was one of the only fighters I remember who wore a suit and tie to our fighter meetings,” said Merchant. “And he would be alone. He didn’t need an echo chamber of managers or an entourage. He was a man of substance, as well as a fighter of substance.” HBO’s Jim Lampley was an unabashed Barrera admirer; some clever fellow could make a funny video loop of Lampley describing Barrera as “among the classiest fighters I’ve met.” He said this nearly every time Barrera fought on HBO, until it sounded as if Lampley was talking about some suave character on a Dos Equis commercial.

Barrera was certainly unique among fighters, not only in that he studied law at La Salle University in Mexico City, but also in that he didn’t come from the sort of crawling poverty that spawns most boxing champions. Indeed, his father worked in the Mexican film industry. Two uncles brought Barrera to a boxing gym when he was 7, and he liked the nervous feeling he got when trying on a pair of gloves. As he progressed through the amateur ranks, his family members would jog with him in the early morning hours to keep him company. It was perhaps this warm, well-off background that irritated his archrival, Morales, who came from the decidedly meaner streets of Tijuana.

Three times they fought, and though Barrera has two official wins, many still argue about the verdicts, especially of the first two bouts. What no one argues about is that the Barrera-Morales trilogy was one of the fiercest in boxing history and that the acrimony on the part of Morales was very real and deep.

“The first fight with Morales was a hard, thrilling fight,” said Merchant. “I don’t remember a more intense fight. There was a social and psychological battle going on between them that fascinated me. It was a personal rivalry, with personal things at stake. I recall Morales, in particular, saying, ‘He’s not in my class,’ which can have many different meanings.”

Morales may have been piqued that Barrera had found his early stardom in Los Angeles, not Mexico. Perhaps it was merely a geographic rivalry of Mexico City vs. Tijuana.

Or maybe he resented Barrera’s style, which combined power with finesse, whereas Morales always looked like he was attacking opponents with a hatchet.

Or maybe, most likely, he resented Barrera’s very existence. After the fans and the press had given up on Barrera being the new Chavez, Morales was thought to be the heir apparent. When the two collided in the ring, they seemed to be fighting for the championship of Chavez, or as Dr. Ferdie Pacheco once said of the Muhammad Ali-Joe Frazier wars, they were fighting for the championship of each other.

“There is always respect between fighters but things are always the same between us,” Barrera said in 2012. “He just doesn’t like me.”

Barrera wasn’t innocent, though. He matched Morales’ barbs and nasty behavior with his own. Moreover, both fighters would be chastised in today’s more delicate climate. These days, ESPN would devote a half hour of SportsCenter to whether the two should be fined or punished for some of the things they said about each other. Times have certainly changed. Fifteen years ago, anyone trying to persuade Morales and Barrera to be more politically sensitive would have had better luck catching a bull with a butterfly net.

With Barrera and Morales it may have been a simple case of, as they used to say in movies about the Old West, the town wasn’t big enough for both of them. Here’s hoping the IBHOF will be big enough, as Barrera will be inducted in June 2017 and Morales is a lock to join him there soon.

As for being the next Chavez, it’s an old line that doesn’t mean much anymore. Sportswriters looking for a headline brought it up and fans found the idea tasty. If the comparison bothered Barrera, he didn’t let on.

“It was a high bar to jump,” said Merchant, “but Barrera did pretty damned good.”

MARCO ANTONIO BARRERA’S GREATEST HITS

The five most important victories in Barrera’s career.

KENNEDY MCKINNEY

Date: Feb. 3, 1996 • Site: Great Western Forum, Inglewood, Calif. • Result: TKO 12 • Background: Barrera, making the fifth defense of his WBO 122-pound title, dropped McKinney five times. Still, this was no blowout. McKinney fought hard and even put Barrera on the canvas in Round 11. The barrage that ended it at 2:05 of the 12th showed Barrera at his most ferocious; he practically sneered as he pounded McKinney into submission.

ERIK MORALES I

Date: Feb. 19, 2000 • Site: Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino, Las Vegas • Result: L SD 12 • Background: Wearing the WBO junior featherweight crown a second time, Barrera faced WBC kingpin Morales in this highly anticipated contest. The resulting fight was good enough for HBO’s Jim Lampley to bellow before the final round, “It’s been an unforgettable war!” Though Barrera lost, his star rose in the RING Fight of the Year.

NASEEM HAMED

Date: April 7, 2001 • Site: MGM Grand, Las Vegas • Result: UD 12 • Background: Hamed was the undefeated hotshot with the knockout punch, while Barrera was a 3-1 underdog. Ignoring the naysayers, Barrera avoided heavy exchanges and put on a display of pure boxing. “The key to that victory was to not be intimidated by any of his antics,” Barrera said later. “On the contrary, to not show any respect to him.” He didn’t.

JOHNNY TAPIA

Date: Nov. 2, 2002 • Site: MGM Grand, Las Vegas • Result: UD 12 • Background: The always entertaining Tapia was an aging warhorse by the time of this bout, but he gave a very good account of himself. Meanwhile, Barrera boxed brilliantly, winning by scores of 116-112, 118-110 and 118-110. The fight was much closer than the cards reflected. Tapia said it was an honor to fight Barrera, calling him, “the true king of the featherweights.”

ERIK MORALES III

Date: Nov. 27, 2004 • Site: MGM Grand, Las Vegas • Result: MD 12 • Background: The rubber match wasn’t expected to be so intense, but it was named THE RING’s Fight of the Year, with Round 11 taking Round of the Year honors. The two old rivals tore into each other just as they had more than four years earlier. One judge called it a draw; the other two scored narrowly for Barrera. It was a thriller.