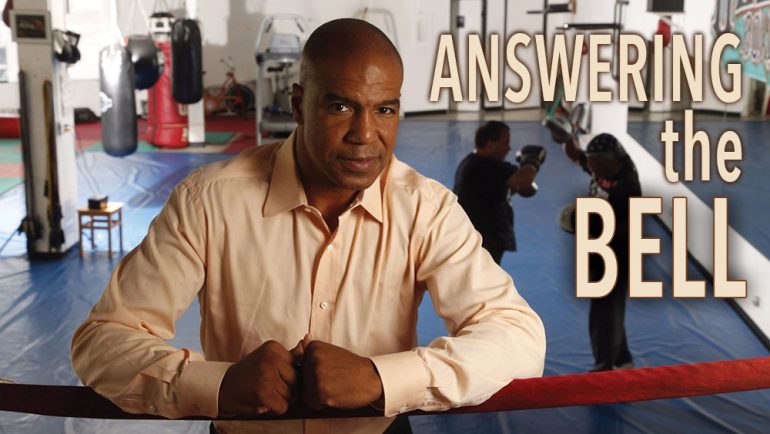

AFTER TRAGEDY IN THE RING, PAUL VADEN FOUND HIS CALLING IN MOTIVATING OTHERS TO OVERCOME ADVERSITY

For many prizefighters, making the transition to life after boxing is difficult. Gone for good are the rush of fight night and the energy of the fans. They often find themselves looking back upon their glory days rather than living in the present. But if you ask 50-year-old Paul Vaden, he’ll tell you that his best years are far ahead of him. He still lives in his hometown of San Diego, where he is a sought-after corporate mentor, motivational speaker and author. Boxing will always be a part of what he refers to as his “script,” but it would only be the beginning. “Ever since I was 4 years old, I wanted to be a boxing world champion,” Vaden told The Ring. “But then I wanted the rest of my script to play out. As I started to grow, I understood that there were other things I would do to impact this world. I don’t know how to describe what I do today other than I help people win.”

From a young age, Vaden was inspired to be beyond labels. “I have two superheroes in life: Muhammad Ali and Michael Jackson,” said Vaden. “To call them just a fighter, just a singer, would be a disservice. I wasn’t a fan of them; I studied them.” Like many children in the 70s, Paul became enamored with Ali the instant he saw him. Watching his heroes perform and seeing the impact they made on the world made a lasting impression.

The Vaden family lived in the rough southeast section of San Diego. Paul’s father, Gerald, wanted his two sons to get involved in sports to keep them out of trouble. In the summer of 1976, upon the backdrop of the Montreal Olympic Games where the American boxing team would collect five gold medals, he took his boys to the Jackie Robinson YMCA off Imperial Avenue. Inside the facility, Paul came across a boxing room that was donated by the great Archie Moore; right then and there he knew what he wanted to do. “My father gave me a two-week trial, probably thinking that I would lose interest after a couple weeks and choose to do something else,” said Vaden. “But once I had found my outlet, I was all in. I would be at the gym early every day.”

Vaden would go on to compile a stellar amateur record of 327-10. In 1988, he came up short qualifying for the Olympics Games in Seoul, South Korea, losing a controversial decision to eventual welterweight bronze medalist Kenneth Gould. Shortly thereafter, while still an amateur, Vaden adopted what would become his professional ring moniker when an article written about one of his bouts described it as “an ultimate performance.”

Paul Vaden (here fighting Richard Evans) was a cerebral boxer who could be flashy and fierce. (Photo by Holly Stein – Allsport/Getty Images)

“When he said I gave ‘an ultimate performance,’ he wasn’t just talking about what I did the ring, but me being gracious and articulate outside of it,” Vaden said. “I liked that word – ‘ultimate’ – because it had more to do with the person I was trying to become. I wanted to be seen as more than the fighter, but the whole package, like my superheroes.”

After winning the national amateur championship at light middleweight in 1990, many felt Vaden was a shoe-in for the upcoming Barcelona Games in 1992. However, Paul opted to turn professional instead, feeling like many that the electronic scoring system recently adopted by the International Olympic Committee was heavily flawed. Besides, the goal he always had for his script was to become a professional boxing champion. So Vaden turned pro in 1991 and reeled off 10 quick victories over his first year. However, tragedy would strike just three days before his 11th fight as his father died of a heart attack. “It was extremely difficult, because he was so supportive of what I wanted to become,” said Vaden. “But it was important that I went through with the fight, because my father would have wanted me to. I would use his death as additional inspiration to fulfilling my dream of becoming champion of the world.”

In August of 1995, Vaden had his first title shot, facing Baltimore native Vincent Pettway for his IBF junior middleweight championship. A betting underdog coming in, Vaden won via 12th-round TKO, fulfilling a promise he had made to classmates back in the 3rd grade. “I made a declaration to my class that I would be world champion,” said Vaden. “Looking back, I needed to become champion to add fuel to the vehicle for what I do today. Becoming a world champion, all the hard work it entails, that lends credibility to my message at public speaking events today.” Instead of milking his title with optional defenses, Vaden went straight into a unification match with the great Terry Norris just four months later. A well-documented history of animosity had existed between them for years. This was not the typical played-up shoving match between fighters at a weigh-in; this was the real thing.

Although Norris was a Texas native, he trained and fought out of San Diego. “Terrible” Terry claimed that he had broken Vaden’s nose during a sparring session in the early ‘90s, calling him a “crybaby.” In retaliation, Vaden became romantically involved with Kelly Norris, Terry’s wife. Both fighters traded insults through the media for years. Norris said things about Vaden’s late father that enraged him; Vaden wrote a malicious poem about Norris that was posted in an issue of The Ring. “It was a really hostile environment whenever we were together,” said Vaden. “Not just for us, but it was uncomfortable for everyone around us.”

Boxing fans were anticipating an action-packed grudge match when they faced each other on December 16, 1995, at the Spectrum in Philadelphia, but it was not to be. Norris, an eventual inductee into the International Boxing Hall of Fame, would go on to win a one-sided decision over 12 rounds. Humbled, Vaden chose to look at this first loss as a learning experience. “When you go to the scorecards of life, I was wrong (for the affair). I believe that God is a teaching God. He picked that moment to humble me, to teach me.”

Vaden’s first professional loss was to fellow 154-pound titleholder (and hated crosstown rival) Terry Norris (right), who scored a one-sided unanimous decision in December 1995. (Photo by Al Bello – Allsport/Getty Images)

Two years later, Vaden would get a crack at the WBC middleweight title against Keith Holmes. The defending beltholder dropped Vaden twice in the fourth round and once in the 11th before the fight was stopped. Having suffered his second loss as a pro and his first stoppage defeat, Paul felt he needed a break from the ring. He wanted to spend some quality time with his 1-year-old son, Dayne, and his wife, Lisa. It was during this time that he realized his ability for connecting, listening and helping people. Vaden began teaching people how to box, and he soon discovered that he loved the interpersonal part of it more than anything. “In the midst of a workout there are a lot of conversations and you learn about people and their lives, their problems,” said Vaden. Along the way, he would share his ring stories, his struggles, how he overcame them to succeed. The message got through to his clients and relationships soon developed. Unbeknownst to him at the time, Paul was planting the seeds for his eventual work in the corporate sector. But after a year-and-a-half away from his first true love, “The Ultimate” was itching to get back into the ring. Little did Vaden know his script was about to change forever.

Paul returned to the ring in the summer of 1999, scoring a stoppage win that set him up for a bout against Stephan Johnson on November 20 at the Trump Taj Mahal in Atlantic City. The result would be tragic. After nine grueling rounds, Johnson was knocked out in the 10th and never regained consciousness. Johnson was pronounced dead 15 days later.

“I was dying inside during the torment of those two weeks,” said Vaden. “When I learned that Stephan passed, it was a numbing feeling.” Johnson had been briefly hospitalized and placed on medical suspension after a knockout loss to Fitz Vanderpool in Toronto earlier that year. Yet he fought twice in different jurisdictions prior to facing Vaden. According to the New Jersey State Athletic Control Board, Johnson had passed a CAT scan, an electrocardiograph and an eye test prior to the bout. Still, many wondered if accumulative head trauma had carried over into the ring on that fateful night in Atlantic City. Regardless of how it happened, one lasting image haunted Vaden. “He fought me in the ring and never opened his eyes again. Seeing him being carried out of the ring on a stretcher unconscious, I was done as a fighter. I never wanted to experience that again.”

For Vaden, the Johnson tragedy topped off what had been a devastating year for him and his family. That January he had lost a cousin to suicide, and in August his cousin’s father also committed suicide over a sense of guilt. All of the death in such a short time paralyzed Vaden. He didn’t feel like “The Ultimate” anymore. Rather, he felt survivor’s guilt and worried that he was going to be paid back in some way. “I became scared to run, scared to do anything. I thought I was going to drop dead,” said Vaden. “If I had a scratchy throat, I thought it was throat cancer. If I had pain in my legs, it was multiple sclerosis. I was becoming a hypochondriac, calling my doctor all the time.”

‘I’m constantly trying to evolve, cultivate and create awe-inspiring things in this life. I have so much in my head that I want to do, so much that I want to achieve still.’

This was the point in Vaden’s script where he was either going to get stuck or turn the page. In his darkest hour, he did what a fighter does; he returned to the place he had always gone for refuge. “I had to fight to find out if I still had permission to live,” said Vaden. “I needed to go to the thing I had always gone to to find out my answers and try to move on. There were so many other things that I wanted to do in life.”

On April 15, 2000, just months after the Johnson bout, Paul Vaden climbed back into the ring to face Jose Flores in Las Vegas. In the fifth round, Flores caught Vaden with a flush shot, hurting him, but the former champ fought back and went the full 12 rounds. He could care less that he had lost a unanimous decision on the scorecards; he had fought his way back to living again. “I didn’t come into that fight to win or lose; I trained to find out if I was going to live or die,” Vaden said. “The boxer in me had retired after the Stephan Johnson fight. This was not about boxing. When I heard the final bell, I knew my script was just beginning.” He would never fight again, announcing his retirement after the Flores bout, yet “The Ultimate” was back. There was no more fear of death. Matters that seemed larger than life before now appeared trivial, including his previous feud with Terry Norris.

That same year, the Nevada Athletic Commission unanimously denied Norris a license to fight. He was having issues with his balance, slurred speech, and would subsequently be diagnosed with Parkinson’s syndrome. “When I heard about his situation, my heart went out to him. I almost had tears in my eyes,” said Vaden. “But I was also happy that they didn’t give him a license, because I didn’t want anything to happen to him. That opened my eyes to the fact that I cared for him, which made me realize that all of that riff-raff stuff from before wasn’t that deep.” Vaden bumped into Norris at a weigh-in of all places in 2001. The men talked, shook hands and then instantly all of the drama from the past was no more. “I wish him nothing but heaven,” said Vaden. “I am honored to have shared the ring with this great Hall of Famer.”

With his fighting days and grievances behind him, Vaden dedicated the next chapter of his script to helping others. “When I talk about the script of my life and having an impact on others, this is how I could do it,” said Vaden. “All those situations that had me paralyzed – I knew there were people that needed to hear my story to get them out of bed in the morning, to get them to push one step further.” So he picked right back up where he had left off during his break from the ring a few years before, teaching people how to box again. Rather than working out in the often-intimidating confines of a boxing gym, Vaden would work with people one-on-one in their homes. There they would not only feel comfortable to learn the sweet science, but also open up about their lives. “I wanted my clients to feel they had the freedom to express if something was going on with them,” said Vaden. “People need to feel like they have someone to talk to that will listen, someone who wants them to win. I never even saw myself as a boxing trainer; I wanted to be more than that.”

As Vaden developed relationships with his clients, they began to tell their friends. Word spread that this former boxing champion had a knack for connecting with corporate leaders, showing them a different way to tackle problems. It was as if they were in training camp preparing for a fight, only the opponent was a merger, a stockholder meeting, a project overseas, or perhaps a family issue. One of his clients was former Qualcomm president Steve Altman, who became so impressed with Vaden that he invited him to speak at his company. Along the way, Vaden met and worked with Peter Seidler, the managing director of the San Diego Padres, Chris Lischewski, CEO of Bumble Bee Foods, and many others. Before long, Vaden was standing behind the podium at corporate functions sharing his life and loving every second of it. “I’ve never been nervous about public speaking,” said Vaden, “I see it as telling a story through conversation that I’m going to dominate. What I actually get nervous about is the technical side of things, but never what’s going to come from my mouth and heart.”

Beyond working with corporate executives, Vaden works with young people as well. He has spoken at the University of California, San Diego State, Evergreen State College and other schools. He sits on the board of directors at the National Conflict Resolution Center, is the board president of the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation and is heavily involved in the Big Brothers Big Sisters of America. Dayne, his now-21-year-old son, is his pride and joy, and has been able to attend several of his speaking engagements. “I hope he’s impacted by his dad’s ability to convey a universal message and give people higher hope,” said Vaden. Although Paul and Lisa divorced in 2009, they stay in contact and have a good relationship. “I’m forever indebted to her,” said Vaden. “She gave me the greatest gift I’ll ever receive, our son Dayne. I’d do anything for her.”

In 2013, Vaden wrote a book named Answer the Bell, which focuses on giving people the skills to learn, grow and improve their lives every day. “Answer the Bell is about never relenting,” said Vaden. “When things are against you and the weight is too heavy, you still get up. There is always sunshine behind that dark cloud. But you never get the answer in these situations if you don’t answer the bell. If you don’t, you become a ‘coulda, woulda, shoulda.’ You live a life of speculating; you never get past that dark cloud.” On the back cover of the book there is a statement from none other than former Qualcomm president Steve Altman expressing his gratitude for Paul’s friendship.

In 2016, a documentary short film chronicling Vaden’s life was released. Vaden Versus contained archival footage from Paul’s career as well as segments with his former trainer Abel Sanchez, HBO’s Jim Lampley and Hall of Fame journalist Steve Farhood, among others. The documentary features the day Vaden was inducted into the Breitbard Hall of Fame, which honors athletes who have either excelled in sports in San Diego or native San Diegans who have excelled in sports elsewhere. Paul received his induction at the 70th annual “Salute to the Champions” dinner in downtown San Diego; it was one of the proudest moments of his entire athletic career. The film would go on to air at several festivals throughout America and win the Platinum Reel Award at the Nevada Film Festival.

The former champ still works out every morning. As he puts it, he wants to remain “fight ready” so that he can be prepared to help people at any time. Although he always returns to his safe haven to remain in championship form, he never stops looking forward. “I don’t forget where I come from, but I don’t stay stuck,” said Vaden. “I’m constantly trying to evolve, cultivate and create awe-inspiring things in this life. I have so much in my head that I want to do, so much that I want to achieve still.” Later this year, Vaden is releasing a book of romantic poetry he wrote, named Condition of my Heart. He is even working on putting together a musical. “I’ve had a great idea for a musical for over a decade now,” said Vaden. “Sometimes in life the script doesn’t quite line up with the music, but now things are starting to come together. The right people are getting involved.”

A former world champion boxer doing a musical? That’s rare. Penning a book of romantic poetry? That’s definitely a first.

Spend more than five minutes with Paul Vaden and you’ll find yourself infected by his positive energy. At 50 years old, he moves and talks faster than most people half his age. Clearly, there is still plenty more to The Ultimate’s script.

Michael Montero can be found on YouTube, Twitter, Facebook and Instagram @MonteroOnBoxing.