Three Minutes: Corrales vs. Castillo I – Round 10

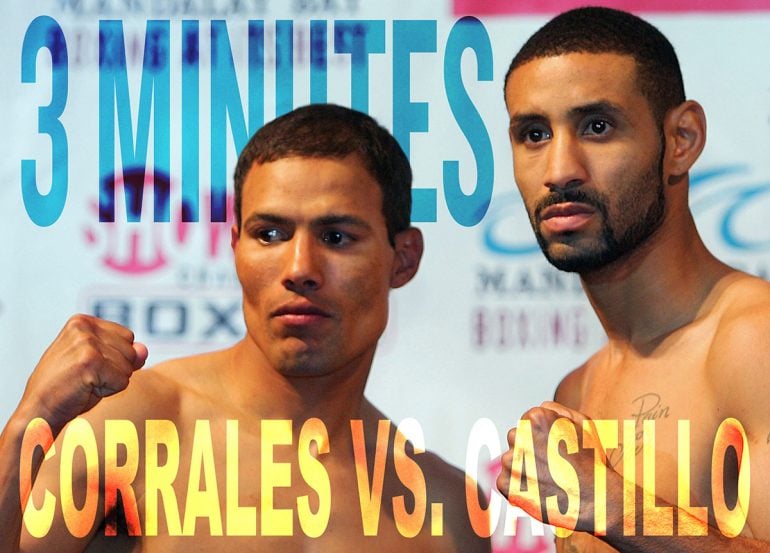

The first fight between Diego Corrales (right) and Jose Luis Castillo will go down in history as having one of the single greatest rounds ever seen in a boxing ring. (Photo by Nick Laham/Getty Images)

Has it really been 18 years since the epic first confrontation between Diego Corrales and Jose Luis Castillo? Has it really been 16 years since Chico’s untimely passing? The following article originally appeared in the April 2023 issue of The Ring.

Diego “Chico” Corrales should be living it up as a retired boxing legend now. He should be cherishing his wife and children. He should be spending time with his loving mother, stepfather and the two brothers who idolize him. Basically, he should be enjoying his existence and easing towards middle age in the comfort of the substantial spoils he earned the hard way throughout an 11-year, 45-fight professional boxing career.

But he’s not, of course. A motorcycle accident in Las Vegas claimed Diego on May 7, 2007, on the second anniversary of his epic meeting with Jose Luis Castillo. And anyway, those who knew Chico best will tell you that he was not a man to ease himself towards anything in life. Rather, the natural ardency of his soul propelled him along with an often-reckless abandon. It can be a lazy writer’s cliché that a warrior fighter’s trials in the ring reflect a fraught life on the outside, but for Corrales at least, there is some truth in drawing such a parallel.

Every day, and every round, was a roll of the dice for Chico, and he never stopped chasing longer odds and higher stakes. It is a mindset that forges greatness and blesses us with heroes. But it is the same mentality that tempts tragedy and robs us of some of our finest before they even reach one score and ten.

During a childhood mottled with the violence that was part and parcel of gang culture on the streets of Oak Park, Sacramento, fighting chose Corrales as much as the other way around. An abusive and alcoholic biological father exited the scene mercifully early, so it was his mother, Olga, and the man Diego would call his real father, Ray Woods, who raised him and his brothers, Esteban and Daryl.

Woods happened to be the boxing director at the Sacramento Police Athletic League, and with little Chico displaying a keen nose for trouble and a penchant for scrapping on the street, the boxing gym quickly became an environment within which his excess energy and anger could be controlled or spent with minimal collateral damage.

After an amateur career that contained just a handful of defeats in more than a hundred contests, he turned pro and let his heavy hands compile a 33-0 record. At just 22 years of age, he claimed the IBF junior lightweight title from the unbeaten Roberto Garcia, now one of boxing’s foremost trainers. Future pound-for-pound king Floyd Mayweather Jr. was the same age, and when Corrales signed a seven-figure deal to face the WBC champ in early 2001, it looked like the only direction his life was headed in was up.

(Photo by Nick Laham/Getty Images).

In fact, the exact opposite was true. Mayweather put a weight-drained Corrales down five times in the MGM Grand before Woods brandished a white towel in the corner to save his son from himself. Chico soon descended much further when convicted of domestic abuse following an earlier violent confrontation with his pregnant wife, Maria. He was an all-or-nothing type of guy, and as he began a 14-month stay in the Deuel Vocational Institution correctional facility, he was certainly closer to securing the latter.

José Luis Castillo fought Mayweather as well. A year after he outclassed Corrales, Floyd stepped up a division to challenge for Castillo’s WBC lightweight title. Pretty Boy was awarded the decision but, to this day, there are many who believe the Mexican deserved the nod. In a rematch eight months later, Mayweather learned from his mistakes and won more convincingly, but it did nothing to diminish Castillo’s standing as one of the great lightweights of his time.

Born in Empalme, Sonora, halfway down the coast of the Gulf of California, Castillo served his apprenticeship in the notoriously punishing environs of Mexicali and Tijuana. He accepted the moniker “El Temible,” meaning the fearsome one, and in knocking out 17 of 18 featherweight opponents while still only a teenager, he did his best to live up to the nickname. By the time he was 24, he’d lost a few cracks at national titles, but everything in life is relative. Such is the country’s depth that there is no shame finishing second in a contest to be the best Mexican in any weight class below 140 pounds.

By the new millennium, he’d matured into the 135-pound body that would prove to be his optimum fighting build. And in June of 2000, he shocked the world by ripping the WBC strap from around the highly rated Stevie Johnston’s waist. Mayweather proved too slippery in a pair of defeats, but Castillo recovered and bested Juan Lazcano, Joel Casamayor and Julio Díaz in consecutive fights between 2004 and 2005. El Temible was back on top of the world.

Diego Corrales was waiting for him at the summit. He had served his time and emerged from prison a bloated 180-pounder who would have struggled to make weight for a light heavyweight bout. But Chico was still only 25, and a perceived injustice at how the particulars of his conviction had played out in the media and affected his family ensured a fire fueled by dreams of revenge and redemption raged within.

(Photo by Nick Laham/Getty Images).

He walked straight back into the gym, reeled off four stoppage wins in less than five months, and then collided head-on with the Cuban Casamayor in a firework display in the Mandalay Bay Casino. Both men hit the canvas and both were in trouble before the fight was halted at the halfway mark. A splintered gum shield had shredded the inside of Corrales’ mouth and, though he pleaded with the ringside doctor through a mouthful of his own warm blood, the medic had to end it.

Chico reversed the result by winning a split decision in a rematch five months later, and few then would have begrudged him a few months of well-earned laurel resting. Instead, he vacated that hard-won WBO 130-pound belt and immediately challenged the unorthodox, hard-hitting and unbeaten Acelino Freitas for the 135-pound version. It was another classic in which Corrales was losing before he dropped “Popo” in the eighth, ninth and 10th to elicit a não mais from the Brazilian champion.

The quest to dominate a heavily stacked lightweight division had effectively been whittled down to two men and, with little fuss, Diego Corrales versus José Luis Castillo, holder of the prestigious Ring Magazine title, was made for Las Vegas on Cinco de Mayo weekend, 2005.

(Photo by Nick Laham/Getty Images)

Though nobody could have foreseen just how special the fight would be, there was undoubtedly an air of heightened expectation before the first bell. Mexican legend Julio César Chávez accompanied Castillo on his ring walk, while the recently vanquished Freitas was seen in Corrales’ posse. At ringside, the likes of James Toney, Winky Wright and Shane Mosely all looked thrilled just to be there as fans.

These were two massive lightweights in every sense of the word and neither possessed a reverse gear. Having never been down in 59 contests, Castillo’s chin was thought to be impenetrable, while Chico was widely regarded as one of the pound-for-pound hardest punchers in boxing. The American was on record as saying he would go through hell and die in the ring before quitting, while Castillo was born with the grit in his soul that is a prerequisite of all great Mexican fighters. With two such ferrous wills to win colliding, something or nothing or everything had to give.

Both understood implicitly that in boxing, as in life, you often have to take before you can give. And what they prized more than anything was the glory bestowed on those fighting men who leave it all in the ring and give the fans a night about which all in attendance can later boast, “I was there.” There are no guarantees in boxing, but it is fair to say that if the styles of any two fighters could be relied upon to blend together into a perfect fistic cocktail of action and heart and skill, it was Corrales and Castillo.

The opening stanza set the tone but was not without its subtle surprises. The Mexican was more renowned for roughhouse tactics, but as both combatants sought to seize the initiative, the rangier Corrales showed he was just as prepared to mix it up on the inside with low blows, forearms and rabbit punches. In response, the partisan crowd let loose with the first chants of “Ka-Stee-Yo! Ka-Stee-Yo!” When referee Tony Weeks stepped in at the bell, they were already slugging toe-to-toe.

Both understood implicitly that in boxing, as in life, you often have to take before you can give.

They spent the second even closer together. It was said that Corrales’ own father feared for his son against the heavier, more rugged Castillo, and Chico now looked to be proving a point. With a two-and-a-half-inch height advantage, the American should have been boxing at distance, controlling the space with a stiff jab, and making room to leverage the power his famous long arms could generate. Instead, he burrowed in close and brawled, apparently content to trade trenchant hooks until someone landed a big one. Perhaps it was a private message to his old man: You shouldn’t have doubted me after that fifth knockdown against Mayweather, Dad, and you shouldn’t be doubting me now. I’m tougher than all these guys.

While Castillo had famously never been decked in 15 years, Corrales had already climbed off the canvas eight times in his professional career. As his chin absorbed right uppercut after brutal right uppercut in round three, it looked like a ninth knockdown was a simple matter of time. Then, midway through the fourth, a gaping wound appeared in the flesh just above Castillo’s left peeper where his eyebrow tailed off. It may have been the work of Corrales’ slashing right hands, but it was ruled an accidental head butt, meaning that if the blood flow caused a stoppage from the fifth onwards, we would go to the scorecards.

Corrales was by now occasionally taking a step back to open up the fight and snap off a couple of jabs before swinging for the fences, but they were mere fleeting digressions from the attritional infighting that was dominating the battle. Success from these close-quarter exchanges were being evenly shared as they took it in turns to land first or hardest. A flurry from Castillo at the end of the sixth probably won him the round and had a young Julio César Chávez Jr. bouncing jubilantly beside his father four rows back.

(Photo by Nick Laham/Getty Images)

Corrales roared back in a seventh in which an inflating bubble of purple flesh on his cheekbone threatened to swell his left eye shut. Perhaps spurred on by the sudden dwindling of his vision, he landed a sweet left in the dying embers of the round that caused Castillo to involuntarily curtsy in recognition. The brutal intensity continued to build throughout the eighth and ninth as we all began to wonder where on earth, or elsewhere, this fight was taking us. It didn’t so much ebb and flow as violently hurl itself from one corner to another. When one man was wobbled or buzzed, he always seemed to instinctively unleash an immediate juddering reply to prevent his foe gaining the momentum a clean hit normally affords. The result was a ferocious war on a knife edge.

At a time when lassitude ought to have been taking its pricey toll, there was simply no let-up. More than that, the accuracy and voracity of the attacks endured unabated. Each round was an incessant show of quality and commitment to the cause, totally devoid of any hint of the trumpery that other fighters employ to steal a second or two of respite when the pace suddenly ups. The standing ovations that greeted every concluding bell just kept growing in volume and duration.

When the fighters rose for the tenth, Corrales’ right eye was now also beginning to swell out of view while his left had become little more than a slit. As the ref checked the tape on Castillo’s gloves, Chico, as was his custom, blessed himself. The two men then touched gloves, something they had not done habitually at the beginning of the previous nine rounds; looking back it is almost as if they knew.

The standing ovations that greeted every concluding bell just kept growing in volume and duration.

Ten seconds in, a short electric left that Corrales probably suspected was designed for his temple kept low and caught him flush on the chin to send him down in installments. The punch took mere milliseconds to throw, but a full three seconds more were needed for Chico’s crumpled body to complete the journey to the canvas floor. From bowed head, he dropped to a knee. From that knee he toppled sideways onto a supporting elbow. There, his center of gravity continued ricocheting around his core and the reverberations rolled him onto the flat of his stomach. From this position he spat his gum shield out, rose as far as his two knees, glanced at his corner, and then focused on the referee’s count. At eight, he stood up.

“Do you want to continue?” Weeks asked him. The question was as good as rhetorical.

Corrales’ trainer, Joe Goossen, did his best to buy a few extra recovery seconds by prevaricating with the mouthpiece as the ref implored him to reinsert it, but he was surely merely delaying the inevitable. An impassive Castillo, the only calm Mexican in the house, stood patiently in the neutral corner and he could see that Chico was gone.

Ten seconds later, Corrales fell again, another slow collapse onto the ring floor the result of a couple of left hooks and a right uppercut through a now-faltering guard. His gloved fist fumbled to again remove his gum shield, a gesture that in another fighter would have signalled that he’d had enough. He then rolled over, eyed the referee, and rose once more. This time at nine and more gingerly than before.

He wandered sleepily to his corner as Weeks rightly deducted a point for the mouthpiece shenanigans. The gregarious Goossen, his standard garish shirt giving him the appearance of a Miami Vice bad guy, was waiting. “You gotta fucking get inside on him now,” he growled. Joe has acting credits himself, but in the movie of this story, Nick Nolte is tailor-made to play him.

When Corrales turned, there was a discernible change in his countenance. It wasn’t that the weariness had dissipated, but he somehow managed to muster a spark to light where before the deleterious effects of the knockdowns had caused only darkness. Suddenly Chico was alive again.

(Photo by Nick Laham/Getty Images).

While still in retreat, he was at least now slipping as many punches as he absorbed. Then, out of nowhere, he landed a right hook that jolted Castillo. A left then pushed the Mexican back on the ropes, where they continued to plow into one another with renewed purpose. One way or another, they were going to end this now.

A banging right and a couple more cuffing lefts shunted Castillo to an adjacent side of the ring. He was flotsam on the tide now but was still attempting to fire back. Corrales paused momentarily and then planted his feet and whaled. This was to be the site of the final stand. Chico’s back is to the camera, but I imagine him simply swinging with his eyes shut, waiting to either stop or be stopped.

(Photo by Nick Laham/Getty Images)

Weeks, who was excellent throughout the fight, was in position, poised to interject at that sickening moment a fighter’s neck turns to jelly and his heavy head lolls drunkenly and defenselessly. It arrived at two minutes and six seconds. Corrales simply raised his right hand, spat out his gum shield, and walked away. It was truly remarkable.

It was fitting that Al Bernstein, perhaps the most astute, erudite and balanced boxing analyst of the past 40 years, was on hand to offer an immediate assessment of what he had just witnessed from ringside.

“That might be the single most extraordinary comeback within a round to win a fight …” he began before pausing, almost as if he understood the historical significance of what had just transpired and wanted to ensure he did not taint it with unnecessary hyperbole or bombast. Having checked himself, he continued with his train of thought, “… that has ever happened.”

The two warriors embraced and praised one another before Corrales was asked by Showtime’s Jim Gray: “How would you describe this fight?”

“An honor,” was his simple reply.

It was all ours, Chico. It was all ours.