Return of the King

The final re-post from the Oscar De La Hoya Special issue in celebration of The Golden Boy’s 50th birthday is the story of De La Hoya’s last world title victory – and arguably the most satisfying knockout of his hall-of-fame career – the pay-per-view beatdown of Ricardo Mayorga, penned by Ring Magazine Editor-In-Chief Doug Fischer.

WHEN BOXING WAS IN NEED OF A MEGASTAR AND A PAY-PER-VIEW EVENT WITH CROSSOVER APPEAL, DE LA HOYA’S 2006 SHOWDOWN WITH RICARDO MAYORGA DELIVERED

The year of 2005 was a compelling one for the boxing world. Future stars were on the rise, old legends were on the slide, and the top boxers faced each other enough to produce a steady stream of significant fights. Sadly, most of the action went unnoticed by the general public.

The May 7 lightweight clash between Diego Corrales and Jose Luis Castillo produced a slugfest for the ages, but it was witnessed by 5,000 hardcore fans who could barely fill half of the Mandalay Bay Event Center in Las Vegas. Their October rematch, while heavily attended, flopped as a pay-per-view event.

Boxing needed De La Hoya. Did De La Hoya need boxing?

However, with Oscar De La Hoya taking the year off, there were no blockbuster events, not on the level that The Golden Boy usually delivered. De La Hoya’s most recent bout had been a bold-but-failed challenge to middleweight champ Bernard Hopkins, who stopped him in the ninth round with a body shot. Their September 2004 showdown garnered 1 million pay-per-view buys, equaling $56 million, second only to what De La Hoya’s 1999 superfight with Felix Trinidad earned ($71 million) among non-heavyweight PPV events.

The highest-grossing event in 2005 was Trinidad vs. Ronald “Winky” Wright, which took place in Las Vegas one week after Corrales-Castillo I. Trinidad still had some star power, as evidenced by 510,000 PPV buys (generating $25.5 million), but the Puerto Rican hero was so thoroughly dominated by Wright that he announced his retirement shortly after the loss.

Tito wasn’t the only icon to hang up his gloves in 2005. Mike Tyson fought his last fight, a humiliating stoppage to lumbering Kevin McBride, in June.

Casual fans took notice of Tyson, who had not been a PPV force since he set the record with his loss to Lennox Lewis in 2002, but still under their radar were talented and exciting young champions and titleholders, such as Floyd Mayweather Jr., Manny Pacquiao, Miguel Cotto, Zab Judah, Ricky Hatton and Jermain Taylor.

“2005 and 2006 were transition years for boxing,” explained Mark Taffet, the former senior vice president of HBO Sports and head of HBO PPV. “The sport had a number of stars who in subsequent years were to become megastars, but in 2005-2006 those fighters were still rising.”

“2005 and 2006 were transition years for boxing,” explained Mark Taffet, the former senior vice president of HBO Sports and head of HBO PPV. “The sport had a number of stars who in subsequent years were to become megastars, but in 2005-2006 those fighters were still rising.”

Here’s a refresher for those who may have forgotten (or are too young to have witnessed) those highlights:

Mayweather assumed the No. 1 spot in The Ring’s 140-pound rankings with a painfully one-sided drubbing of action hero Arturo Gatti.

Pacquiao was in the midst of his trilogy with Erik Morales.

Hatton dethroned respected junior welterweight champ Kostya Tszyu.

Taylor ended Hopkins’ historic middleweight title reign with back-to-back controversial decisions.

Judah was the reigning undisputed welterweight champ.

Cotto racked up title defenses with breathtaking knockouts.

If you’re wondering what was up with the heavyweights, don’t. The glamour division was not glamorous at this time.

Lewis and his successor, Vitali Klitschko, were retired. Wladimir Klitschko was still in his rebuilding phase following knockouts to Corrie Sanders and Lamon Brewster. Ring Magazine’s heavyweight top five was a revolving door of Don King-promoted beltholders – Chris Byrd, John Ruiz, Hasim Rahman and Brewster – plus an overweight James Toney.

The once-invincible Roy Jones Jr., whose 2003 victory over Ruiz had prompted some to christen him the G.O.A.T., had been brought down to earth with back-to-back KO losses to Antonio Tarver and Glen Johnson. Jones’ one fight in 2005 was a one-sided unanimous decision loss to Tarver.

Just how good was Roy Jones Jr.?

Hardcore fans watched it all unfold and were even willing to shell out an exrtra $50 for the big names, but the drama seldom received interest outside of boxing’s small world.

“There were a number of matchups producing 300,000 to 500,000 pay-per-view buys, including Pacquiao-Morales, Taylor-Hopkins, Mayweather-Gatti, Tarver-Jones and Mayweather-Judah, but the sport needed its million-buy megastar to lift boxing to the level that general sports fans would be talking about,” Taffet said. “That megastar was Oscar De La Hoya.”

Boxing needed De La Hoya. Did De La Hoya need boxing?

Not really, at least not in 2005, according to his older brother Joel De La Hoya.

“He had married Millie (Corretjer) a couple years back (2001), and he was living the life in Puerto Rico,” recalled Joel. “It really seemed like he was done with boxing as far as being a fighter. He had his promotional company, which was growing, but I think he had lost some of his passion for being in the ring.

“The rematch with (Shane) Mosley (in 2003) didn’t sit well with him, especially after it was revealed that Shane took PEDs. He thought he won that fight.”

After the loss to Hopkins, De La Hoya focused on starting a family with Corretjer, a famous Puerto Rican singer.

“Millie was pregnant with their first child, Little Oscar (Gabriel De La Hoya). He was just living the family life.”

However, De La Hoya gradually began to feel the itch to fight again after Oscar Gabriel’s birth on December 29, 2005.

But who would he target in 2006? Marketable dance partners were scarce.

His former foes were either retired, like Trinidad, or trying to climb back up the ladder. Fernando Vargas, who had been on a slow rehab from his 2002 loss to De La Hoya, and Shane Mosley, who had suffered back-to-back losses to Wright, were set to face each other in February 2006.

Wright climbed pound-for-pound rankings with the Mosley and Trinidad victories, but he lacked the boxing style or charisma to attract casual fans.

Judah was upset by Carlos Baldomir, arguably the worst Ring champ ever, in January 2006. And Mayweather and Pacquiao were still too light to challenge De La Hoya, who planned to return as a junior middleweight. (Although Mayweather, who had jumped to welterweight at the end of 2005, would get closer by targeting both Judah and Baldomir in 2006.)

Judah was upset by Carlos Baldomir, arguably the worst Ring champ ever, in January 2006. And Mayweather and Pacquiao were still too light to challenge De La Hoya, who planned to return as a junior middleweight. (Although Mayweather, who had jumped to welterweight at the end of 2005, would get closer by targeting both Judah and Baldomir in 2006.)

Who was left? Enter Ricardo Mayorga.

The Nicaraguan wildman had unified major welterweight titles and earned the Ring championship in 2002-2003, but he made himself a marginal junior middleweight player by winning the vacant WBC 154-pound belt with a one-sided decision over Michele Piccirillo in August 2005. More important to the promotion than the green strap he held was Mayorga’s personality – which was bombastic, unfiltered and extremely nasty. Vargas at the peak of his vitriolic grudge against De La Hoya was a boy scout in comparison.

“There may have been other names offered, but we settled on Mayorga because he brought a lot to the table,” said Joel, an integral part of his brother’s inner circle and training camps. “He had big wins against Andrew ‘Six Heads’ Lewis and Vernon Forrest. He went toe-to-toe with Trinidad, which was crazy, but he gave Tito a hell of a fight.

“But he was the guy to go after, because he was a bully. That was the perfect type of opponent for a comeback fight, because Oscar gets more motivated when he fights bullies.”

By late February, word was out that De La Hoya would face Mayorga on May 6.

“We were thrilled to have Oscar back as we planned and looked forward to the event,” said Taffet, who respected the former welterweight champ’s flair for showmanship as much as his ring resume.

“Ricardo Mayorga was a cigarette-smoking, trash-talking, highly unpredictable personality who had an equally aggressive and unpredictable style that resulted in big victories. Ricardo consistently put on fan-pleasing performances.”

“[Mayorga] was the perfect type of opponent for a comeback fight, because Oscar gets more motivated when he fights bullies.”

– Joel De La Hoya

Some fans, especially the diehards, criticized the matchup. They considered Mayorga to be “damaged goods” due to his savage 2004 encounter with Trinidad, who scored a brutal eighth-round TKO. In fact, Mayorga immediately announced his retirement and took more than a year off following the middleweight bout.

De La Hoya wasn’t thought to be as beat-up as Mayorga, but his 2004 middleweight excursion wasn’t any more successful and it gave him the look of a past-prime veteran. He was fortunate to get a razor-thin unanimous decision over then-unheralded WBO 160-pound titleholder Felix Sturm three months before he challenged Hopkins. Even if he was mentally up for Mayorga, the jury was out if his aging body still had “it,” especially after what would be almost 20 months out of the ring.

Mayorga: Good Fighter, Great Self-promoter (2011)

The boxing world would find out what both fighters had left on May 6, but Taffet knew the general public would be more interested in the buildup to the fight thanks to De La Hoya’s crossover appeal and Mayorga’s foul mouth and pre-fight antics.

“Mayorga was the perfect comeback opponent for Oscar in that he was the anti-De La Hoya in almost every way,” said Taffet, who helped market the event that would be co-promoted by De La Hoya’s Golden Boy Promotions and Don King, who represented Mayorga.

“We named the fight ‘Danger Zone’ because Mayorga presented both perceived and real danger for a returning De La Hoya. At the press conference, we had yellow and black ‘Danger Zone’ tape, blockades and construction helmets, which fed the theme and the mood beautifully.

“Mayorga delivered perfectly, yelling in Spanish with Tony Gonzalez (his attorney) by his side interpreting for the largely English-speaking media audience until, at one point, when Mayorga was clearly screaming about Oscar’s wife – at that time Millie Corretja – Tony wouldn’t dare translate what was said and instead simply whispered ‘Oh dear.’ We knew we had a big fight on our hands.”

“We’ll see if he demonstrates how much hate he has toward me by standing in the middle of the ring fighting with me.”

– Ricardo Mayorga

De La Hoya expected Mayorga to insult him throughout the coast-to-coast, multi-city press tour, but he was caught off guard by how personal the verbal attacks were once they were face to face.

“He really got under Oscar’s skin by talking about his manhood, about Millie and his Mexican heritage,” said Joel. “You know how Oscar is; he’s usually happy-go-lucky, nothing bothers him, but once Mayorga went after his family, it got personal. He didn’t give a shit about what was said about him; he never did. But when you get the family involved, that’s a no-no in his book.”

Mayorga set an amped-up, ugly tone for the promotion at the Southern California presser, which was held in a small ballroom inside the Regent Beverly Wilshire hotel in Beverly Hills:

“Tell your wife to fuck you the morning of the fight so you don’t take a dive like you did vs. Hopkins, faggot!” Mayorga yelled as he grabbed his crotch.

“Remember, I’m the champ! You don’t even know how to represent your own people. Mexicans in East L.A. are telling me to kick your ass!”

(Photo by Stan Honda/AFP via Getty Images)

De La Hoya remained silent for most of Mayorga’s tirade, but was clearly agitated when he finally responded at the podium.

“You disrespected the two things I love,” he said. “First, you disrespected my wife. Now you mention my race. This isn’t a game. I’m going to knock you out.”

De La Hoya carried a new intensity back to Puerto Rico, where his training camp resumed with Floyd Mayweather Sr. in charge as head coach.

“Without a doubt, Mayorga’s trash talk lit a fire under his ass,” said Joel. “That was good because it made him work harder, but we didn’t want him to overtrain or stray from our game plan, which was to stick and move.

“We brought in the toughest local guys to spar with him so he could work on that. We didn’t want Oscar to stand and trade with Mayorga, because we knew he was dangerous. We saw what he did to Vernon Forrest. I watched Mayorga’s fight videos with Floyd Sr. and we saw that he loaded up with everything. We knew Oscar had to be cautious of those big looping punches and catch him in between. But we wanted him to pop that jab and move side to side to get him off balance first.”

Mayorga tried his best to get De La Hoya off balance by telling the media that he would try his best to “stop his heart or detach his retina.” He stepped up his chaotic tactics the week of the fight, which took place at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas, by threatening to pull out if his purse wasn’t increased from a guaranteed $2 million to $8 million (equal to De La Hoya’s guarantee).

Of course, Mayorga was bluffing about not fighting, but De La Hoya assured the media he was serious about going for the knockout.

“It’s nice to hear that he has so much hate for me,” Mayorga told boxing media the week of the fight. “We’ll see if he demonstrates how much hate he has toward me by standing in the middle of the ring fighting with me.”

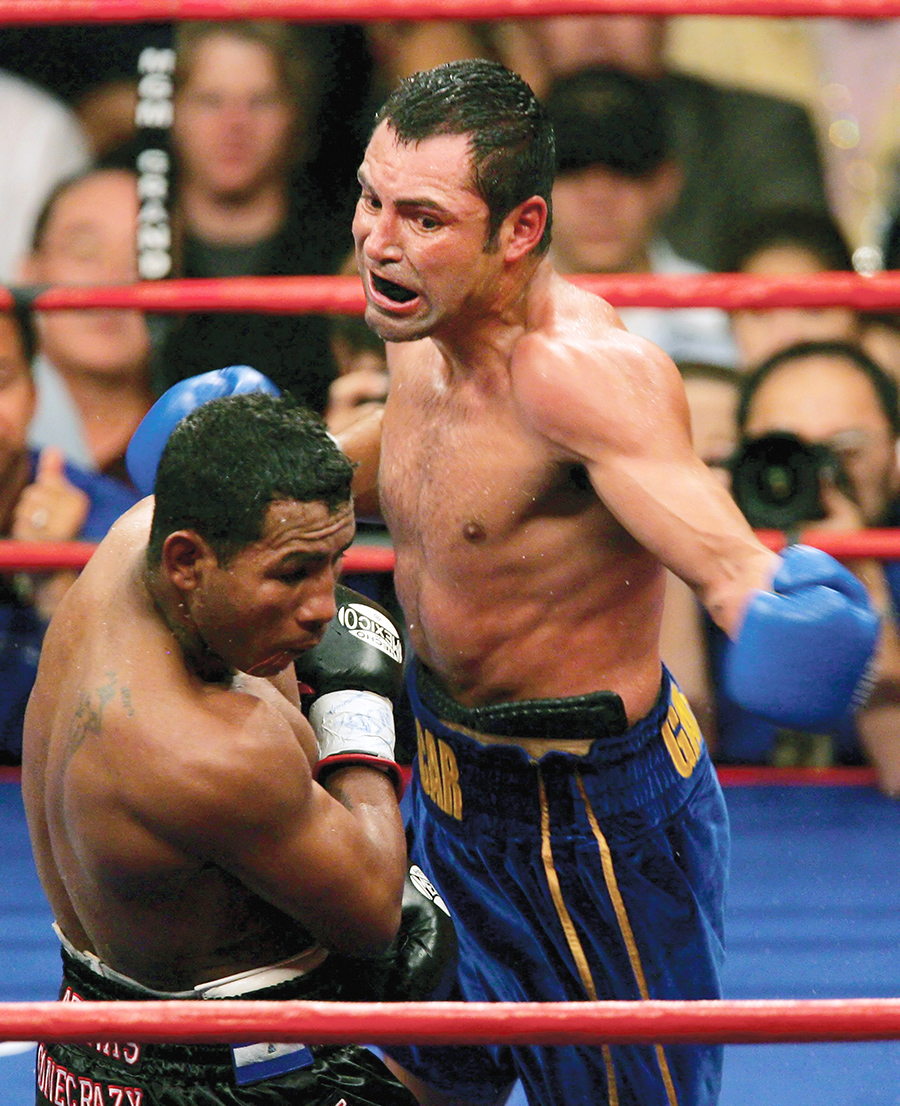

Mayorga got his wish just under one minute into the opening round.

De La Hoya jabbed to the body, forcing Mayorga to drop his hands, allowing for a right cross, which set up a short hook just as Mayorga was winding up with a sweeping hook of his own. Boom! A twisting Mayorga was deposited to the seat of his trunks.

De La Hoya shocked Mayorga – and thrilled fans – by going on the attack early. (Photo by Ethan Miller/Getty Images)

Mayorga got up, more embarrassed than hurt, but he instantly realized that he wasn’t going to have to chase De La Hoya on this night.

“All of the stick-and-move strategy we worked on in Puerto Rico went out the window in the opening round,” said Joel. “[Oscar] went out there and threw caution to the wind; he went out there to bully the bully.

“That was nothing that we worked on. That was just Oscar saying, ‘All right, let’s see who’s got the biggest balls.’”

They both had big balls, as well as granite chins. The fight would go rounds, but De La Hoya’s tighter technique and superior speed, timing and punch accuracy would be the difference in a one-sided but entertaining scrap.

De La Hoya remained laser-focused and in the pocket following the opening-round knockdown. A shaken Mayorga defiantly launched haymakers, most of which De La Hoya calmly blocked with his gloves and forearms.

“I felt confident,” De La Hoya told Mario Lopez during a 2020 DAZN feature that reviewed the Mayorga fight. “I felt that I had his timing, I could see his punches coming, but he was still dangerous. He still hit hard. He could still knock me out. But I had so much anger. I wanted to finish him off.

“I couldn’t do it in the early rounds because he had such a good chin, but every punch I threw, I threw with bad intentions.”

Between rounds, De La Hoya said he caught an earful from Mayweather Sr.

“Floyd Sr. yells, ‘What the hell are you doing? You should have knocked him out!’

“I’m thinking, ‘No, let him come. I’m gonna make him suffer. I’m gonna let him go a few rounds and I’m gonna make him pay.’”

De La Hoya did that over the next five rounds – stalking forward behind a high guard, sharp jabs, sneaky right crosses and his ever-present left hooks – but not without risk.

Mayorga gave ground but didn’t give up trying to knock De La Hoya’s block off, even after he’d been momentarily wobbled by multi-punch combinations, which was often.

“He kept talking shit and he kept throwing bombs,” De La Hoya told Lopez.

They traded flush hooks, uppercuts and body shots. De La Hoya later admitted that some of the punches he took stiffened his legs, but it was Mayorga who was worn down.

One minute into the sixth round, De La Hoya stunned and staggered Mayorga into the ropes, where the weary bully took a knee and grabbed the center rope to steady himself. Pride got him to his feet, but he did so with a resigned look on his face. He realized that De La Hoya’s prediction was about to come true.

To Mayorga’s credit, he went out on his shield. This wasn’t Hector Camacho playing the “bad guy” role to hype an event and collect a payday. Mayorga really tried to win, but he was outclassed and ultimately overwhelmed along the ropes amid a fusillade of punches.

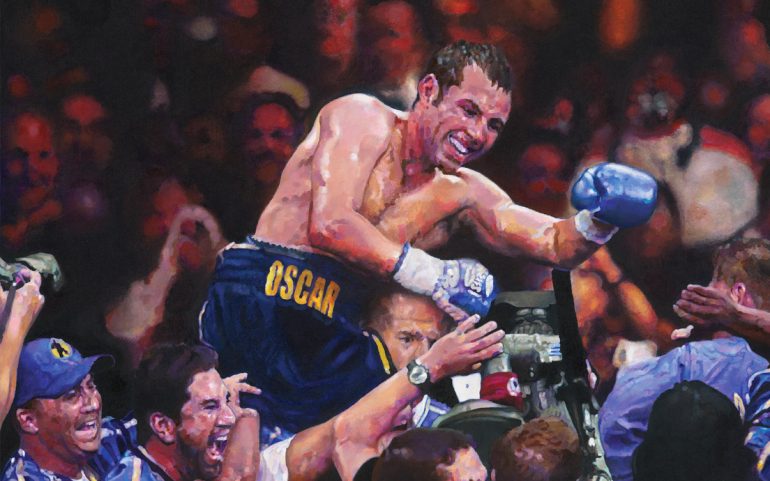

The MGM Grand Garden Arena exploded as referee Jay Nady jumped in to save Mayorga at the 1:25 mark.

“That victory turned out to be one of the biggest moments of Oscar’s career,” said Joel. “The elation we felt, the energy we got from the fans in that moment, it was up there with the wins over Chavez, Whitaker, Vargas.

“It was a special victory because it felt like it was for the De La Hoya family. I remember it was the only time my son, Joel Jr., who was more of a Shane Mosley fan than of Oscar, wanted to get in the ring and congratulate his uncle. We all wanted to celebrate that win like no other.”

It would be the final world title victory of De La Hoya’s career, but it proved he was still a fighter to be reckoned with. The performance of the pay-per-view event – which garnered 925,000 pay-per-view buys, generating $46.3 million – confirmed that De La Hoya was still a megastar.

Some thought the victory was the perfect note for De La Hoya to retire on, but most knew that it would lead to better opponents and bigger goals.

“Oscar De La Hoya was noncommittal regarding his future following his spectacular knockout of Ricardo Mayorga. But I would be astounded if he never fights again,” Ring Magazine Editor-in-Chief Nigel Collins penned in his Ringside column, published a few weeks after the fight.

“Don’t think for one moment that Oscar didn’t enjoy beating the crap out of Mayorga. The Mayorga mauling has reminded De La Hoya just how potent of an elixir such an emphatic victory can be, and he won’t want to let it go before at least one final fix.

“If there is a problem, it is finding the right opponent. Though the pay-per-view public would probably buy it, Oscar’s ego will not permit another fight against a Mayorga-type. The next fight must be a bigger challenge against somebody who will push De La Hoya to be the best that he can be, perhaps for the last time. In other words, somebody like Floyd Mayweather.”