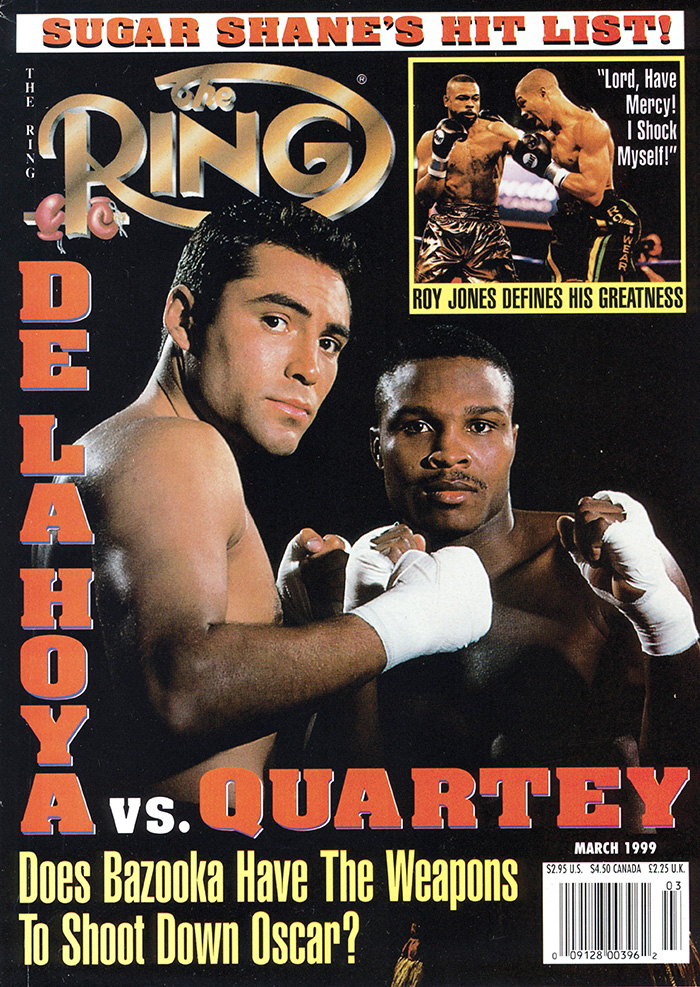

Clear and Present Danger (Oscar De La Hoya’s 1999 welterweight clash with Ike Quartey)

In celebration of Oscar De La Hoya’s 50th birthday, RingTV is re-posting select articles from the September 2022 issue of The Ring, our special edition celebrating the The Golden Boy’s career. The following article, by recent International Boxing Hall of Fame inductee Ron Borges, De La Hoya’s epic welterweight title showdown with Ike Quartey, which took place 24 years ago this month.

IKE QUARTEY REPRESENTED THE FIRST REAL PHYSICAL THREAT TO DE LA HOYA’S WELTERWEIGHT TITLE REIGN, AND THE FORMIDABLE GHANAIAN LIVED UP TO IT IN ONE OF THE GOLDEN BOY’S HARDEST-FOUGHT VICTORIES

Oscar De La Hoya understood what the presence of Ike “Bazooka” Quartey across the ring from him meant. It meant, for perhaps the first time in his career, danger was lurking only the length of a long jab away. De La Hoya insisted before the first bell sounded on February 13, 1999, at the Thomas and Mack Center in Las Vegas that he welcomed its arrival.

In a gambler’s town where most visitors come away losers, the undefeated Golden Boy of boxing was pushing all his chips into the center of that ring. Golden or tarnished? That was the risk Quartey posed that night.

At the time, the 26-year-old De La Hoya was 29-0 with 24 knockouts, but more importantly he was an Olympic gold medalist, a winner of five world titles in four weight classes and 17 straight title fights and the biggest non-heavyweight drawing card in the sport. He had already taken belts from the likes of Genaro Hernandez, Julio Cesar Chavez, Pernell Whitaker and Miguel Angel Gonzalez, all formidable champions although considered flawed in one way or another, either by a lack of size or the ravages of age. Quartey, the undefeated former WBA welterweight titleholder, had none of those issues dogging him.

At the time, the 26-year-old De La Hoya was 29-0 with 24 knockouts, but more importantly he was an Olympic gold medalist, a winner of five world titles in four weight classes and 17 straight title fights and the biggest non-heavyweight drawing card in the sport. He had already taken belts from the likes of Genaro Hernandez, Julio Cesar Chavez, Pernell Whitaker and Miguel Angel Gonzalez, all formidable champions although considered flawed in one way or another, either by a lack of size or the ravages of age. Quartey, the undefeated former WBA welterweight titleholder, had none of those issues dogging him.

Nine months shy of 30, Quartey was a fighter with a piston-like jab, concussion-producing power, a 34-0-1 record that included 29 knockouts and a healthy disrespect for golden boys like De La Hoya. There was only one word to describe what he was at that moment.

“If you can see danger in front of you and feel this guy can beat you, you do everything it takes to win,” De La Hoya said before the fight. “This is a dangerous fight, but I wanted it. I needed this. I was losing my focus. I need dangerous fights now to stay motivated. Sometimes getting ready for [these types of fighters] is easier than getting ready for Joe Schmoe.”

Perhaps so, but the problem with “those types of” fighters is they don’t fight like Joe Schmoe. They come to the arena with supreme confidence and bad intentions, and no one felt the latter more than Isufu “Ike” Quartey, a native of Ghana who had learned to fight in the accepted way. He fought to keep what little he had.

That was long before he wore $250 sunglasses, as he did during fight week. It was when he was a street kid from Bukom, a tough neighborhood in the bowels of Accra, Ghana’s capital city. It was there that Ike Quartey first learned the value of being dangerous.

The youngest of the 27 children of Robert Quartey, a court bailiff with five wives and a hard-earned reputation as a street fighter, Ike grew up hungry, literally and figuratively. As a kid, he once fought savagely to retain ownership of a scuffed soccer ball, one of his few possessions. The kid who tried to take it from him was Alfred Kotey, himself a future world champion whom Quartey would follow into a steamy boxing gym to begin walking their dual roads to fame and fortune. But long before he got to his $3 million moment with De La Hoya, there was the matter of ownership of that scuffed ball to settle.

“You have something someone wants, they take it,” Quartey once said of his boyhood while sitting in a Las Vegas coffee shop. “Back there, you fight in the streets every day. You fight for everything. That is life there.”

Quartey’s fighting life in the ring began when he left his father’s crowded home in Bukom as a young boy to move in with a boxing trainer. If one Googles the word “Bukom,” the second thing that comes up is “Bukom is known for its output of successful boxers to America.” Like Kotey and boxing idol Azumah Nelson, Quartey would become another fighting export of Bukom.

“I left my house at 7 or 8,” Quartey claimed. “My mother did not want me to be a boxer, so I went to live with my trainer.”

Verifying such details of the life of a boy from Ghana is difficult, but one thing was clear by the evening of February 13, 1999: Quartey had learned to fight somewhere. And by the time he faced De La Hoya, he had more than lived up to the reputation of a brother he never knew.

The original Ike Quartey won a silver medal as a light welterweight at the 1960 Olympics in Rome when he was 26, nearly nine years before the younger Ike was born. While Isufu was fighting over a soccer ball, his big brother was off making a living in Mexico. The younger Ike had no recollection of him, but he knew what he had accomplished and so took his name and followed his road through pain to fame, a road that now had led him to face the American Golden Boy whom he’d grown to hate.

There were many boxers who resented the fame and fortune young De La Hoya had amassed since turning pro only six years earlier, but Quartey had another reason for his feelings. He believed the postponement of their original fight date three months earlier had been a ploy by De La Hoya to avoid the fate that now awaited him. De La Hoya withdrew from the original fight date after suffering a cut eyelid in sparring, but the rumor was that he was not in tip-top shape and needed extra time to get ready for the legitimate threat that Quartey presented.

De La Hoya and Quartey finally squared off in 1999. (Photo from The Ring archive)

Quartey’s enmity was exacerbated by what had become a 14-month layoff since fighting to a disappointing draw against Jose Luis Lopez, who had dropped him twice. Quartey’s trainer claimed Quartey had refused to postpone that fight despite suffering with a virus some later claimed was a case of malaria, and he’d later been stripped of his WBA title for choosing to fight De La Hoya for the biggest payday of his career rather than a lesser WBA-sanctioned challenger.

Quartey came to believe that not only had the decision to fight De La Hoya cost him his title, but also that De La Hoya, who now held the WBC welterweight belt, had only agreed to face him after seeing he’d struggled against Lopez. For this, Quartey said, De La Hoya must pay a steep price.

“I want to hurt him because he made me mad,” Quartey said before the fight. “I am going to beat him like he was my son.”

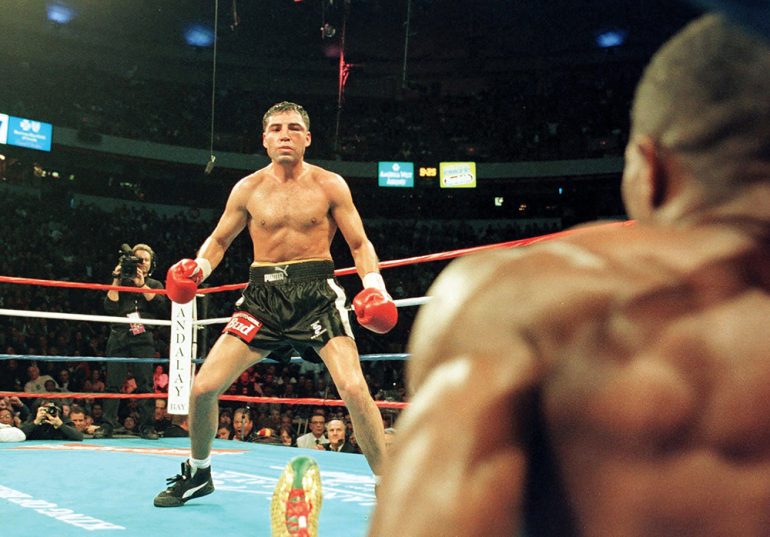

De La Hoya, on the other hand, understood fully what Quartey meant and soon would learn how right he was when Quartey’s stinging jab began to cause his left cheek to swell and his nose to leak plasma barely two rounds into the fight. De La Hoya assumed he’d countered that early offensive when, 10 seconds into Round 6, he landed a perfectly timed left hook that sent Quartey flying backward and down on the seat of his gold satin pants. He skittered along the canvas like seed scattered by a farmer but quickly scrambled up, and within seconds he sent an onrushing De La Hoya to the floor with his own hard left. Shots fired!

De La Hoya had rushed in recklessly, looking to finish Quartey, and missed a wild left uppercut. Quartey countered with a thudding left hook that clearly hurt De La Hoya far more than Quartey had been hurt when he went down.

Following the lessons he’d learned in the streets of Bukom, Quartey attacked wildly as De La Hoya held on, now clearly aware that his concerns about Quartey’s power had been justified. At one point, referee Mitch Halpern briefly called time to warn Quartey for hitting out of a clinch. That seemed to momentarily ease the damage De La Hoya was sustaining, but Quartey came back in Round 7 and resumed pushing his jab into De La Hoya’s face as if he were driving nails into a 2×4.

“I got to figure something out, because if he connects, he can knock me out; and if I connect, I can knock him out.”

– Oscar De La Hoya

When De La Hoya returned to his corner after that round, the left side of his face was swelling noticeably and trainer Gil Clancy implored him to change his tactics.

“You have better legs than the other guy!” Clancy hollered. “Use ’em!”

At this juncture, De La Hoya realized what he had said before the fight was true. This was indeed a dangerous man in front of him, one who required clear thinking as well as hard punching to overcome.

“I can just go in and brawl, but is that the smart thing to do?” De La Hoya had asked before the fight. “I got to figure something out, because if he connects, he can knock me out; and if I connect, I can knock him out. I know what kind of opposition I’m facing this time. This is the first true test of my career. The six years I’ve been in professional boxing were all preparation for this fight. I know the danger. Now we see what happens.”

To that point, what was happening was Quartey controlling the pace of the fight with his jab while taking minimal chances. Something had to be done to break that pattern, and slowly but surely De La Hoya did it with the use of his legs and an ever-increasing punch production.

While De La Hoya had entered the fight with a healthy respect for Quartey, he was firmly convinced the Ghanaian had two significant defects. First, Quartey did well against fighters who stood in front of him but struggled against those who moved laterally quickly. As for the second flaw:

“He doesn’t have the best head movement,” De La Hoya opined. “He’s kind of a straight-up, stand-up fighter whose defense isn’t great. And he tends to fade late. I need to capitalize on that.”

In boxing today, the championship rounds are rounds 11 and 12, the additional rounds where champions are made. So it was on this night. With Clancy urging him to “show the judges you want to win the round,” De La Hoya began to increase both his movement and his punch output. And as he did, Quartey’s production began to slow and De La Hoya started landing more consistent power shots. Gradually, he also began to seize control of the exchanges.

Quartey nailed De La Hoya with a crushing right hand midway through Round 9, but the champion shook it off and landed a hard combination in response that seemed to bring Quartey’s offense to a standstill. Quartey’s once-thudding jab was now arriving less frequently and in single-file fashion while De La Hoya began to attack his body and head with growing ferocity. The tide was turning, rolling in for De La Hoya and running out for Quartey.

De La Hoya snapped Quartey’s head back in the 10th with a hard left and continued to carry the fight to his challenger in Round 11, yet the fight’s outcome still seemed to be hanging from a razor’s edge when the bell sounded to open the 12th and final round.

Perhaps sensing he was on the brink of losing his WBC welterweight title, De La Hoya savagely attacked. Twice he strafed Quartey with sizzling left hooks in the round’s opening seconds and when Quartey launched a right hook in response, De La Hoya avoided it and nailed him with a counter left that sent Quartey sprawling to the floor for a second time.

De La Hoya came back strong in the championship rounds. (Photo by John Gurzinski/AFP via Getty Images)

The smirk Quartey had worn for most of the fight was now gone as De La Hoya swarmed him like a family of angry wasps, raining in blow after blow as Quartey stood pinned against the ropes. As Halpern closed in with concern on his face, Quartey returned fire just often enough to convince him not to stop the fight, though he would have been justified in doing so.

After a minute-long attack, De La Hoya was spent but had made his point. In the most critical moment, he had shown who he was. He was not only The Golden Boy but a “hombre malo.” A baadd man!

Ike Quartey had fought a controlled fight in which he took few chances and paid for it, winning the early rounds with his jab but then frittering away his lead by being outworked and outlanded by De La Hoya. According to CompuBox stats, Quartey threw only 41 punches in Round 10 and 43 in Round 11 before being overwhelmed in the final round, when De La Hoya threw 69 punches and landed an astonishing 41 to Quartey’s 18.

Both fighters celebrated when the battle was finally over. (Photo by Al Bello/Allsport)

“I thought Oscar was going to kill him,” Clancy said later. “He hit Ike with left hooks I don’t think anybody I know could take.”

In the end, judge Ken Morita of Japan scored the fight 116-112 for De La Hoya and England’s John Keane had it 116-113, a spread shared by most at ringside. Somehow, English judge Larry O’Connell gave the edge to Quartey, 115-114, a score most ringside observers found curious and difficult to defend. Quartey was not among his critics, however.

“[De La Hoya] did nothing,” Quartey said despite the fact he spit those words out through a badly swollen right cheek. “I did everything. All he did was come to survive and that is what he did. You saw the fight. You know I won the fight. You know I couldn’t win a decision in Las Vegas.”

De La Hoya emerged bruised but victorious. (Photo: AFP/AFP via Getty Images)

Certainly he couldn’t after being knocked down twice and outworked in the fight’s final three rounds. De La Hoya’s team had analyzed Quartey’s punch data and found he threw considerably less often in the late rounds, a fact they would exploit when this again proved to be the case.

Curiously, De La Hoya continuously ignored his fight plan, however, even after Clancy’s pleas to use his superior speed and movement to keep the more mechanical and methodical Quartey at bay. Instead, he often stood in front of his challenger, looking to trade punches as if to prove a point. In the end, that approach worked but not without a price.

It was over an hour after the fight before De La Hoya arrived at the post-fight press conference. As he spoke, he rubbed a Dixie cup filled with ice against his left cheek and peered through a half-closed left eye as if peeking through venetian blinds.

“I thought I was in total control, but I wanted to go out with a bang,” De La Hoya explained. “I wanted to prove I can fight. I wanted to do everything possible to get a devastating win.”

Clancy conceded De La Hoya “got caught up in it, and showed he has the ability to fight as well as box. He showed a lot of heart, which is what got him through, but he spent the entire fight fighting Quartey’s fight. If he used his legs, it would have been a lot easier for Oscar, but it was one of those nights he wanted to fight more than he wanted to box.”

Three months later, De La Hoya would face Oba Carr, who had given Quartey fits three years earlier, and would knock the Kronk disciple down in the opening round before stopping him in Round 11.

Quartey did not fight for 14 months. When he did, he lost and never again seemed to represent the danger Oscar De La Hoya faced down in what many believe was his greatest fight.