Best I’ve ever seen: Bazooka Limon-Bobby Chacon IV (40 years later)

Every so often, I am asked “what is the greatest fight you’ve ever seen?” Because I’ve been a boxing fan since March 16, 1974 – the date of the fight that ignited my interest, Roberto Duran-Esteban DeJesus II – that covers a lot of ground. For me, though, the answer is easy: The fourth fight between Bobby Chacon and Rafael “Bazooka” Limon, which took place 40 years ago today (December 11).

Inside the ring, Chacon-Limon IV had it all: Constant two-way action, multiple shifts of momentum, a mutual hatred that was conveyed through unvarnished violence, and one of the most melodramatic finishes in the sport’s history. In a year that included classics such as Aaron Pryor-Alexis Arguello I, Ray Mancini-Arturo Frias, Salvador Sanchez-Azumah Nelson and Wilfredo Gomez-Lupe Pintor, it was Chacon-Limon IV that earned The Ring magazine’s “Fight of the Year” award.

But the element that lifted this fight above all others in my mind was the backstory that accompanied it and the extraordinarily fulfilling manner that this fight completed it. Not only was it the culmination of a years-long rivalry, it also marked the triumphant end of a personal odyssey for Chacon that was defined by determination, unconquerable self-belief, persistence, stubbornness and unspeakable tragedy.

This story began on September 7, 1974 at Los Angeles’ Olympic Auditorium when Chacon challenged former WBA 130-pound champion Alfredo Marcano for the WBC featherweight title stripped from Eder Jofre due to his management’s failure to arrange a fight with Marcano, the organization’s mandatory challenger. Chacon won the championship with a ninth-round TKO, and not only did the victory lift his record to 25-1 (23), it set the table for what seemed like a limitless future. He was young. He was handsome. He was charismatic. He had a megawatt smile that brightened any room he occupied and any camera that was pointed at him, television or otherwise. He possessed a dynamic boxer-puncher style that was pure box office. The man nicknamed “Schoolboy” seemed to have it all. And now he was a world champion.

Chacon continued the momentum a little less than six months later by stopping Jesus Estrada to retain the title, and that victory set up a June 20, 1975 showdown with former bantamweight and featherweight champion Ruben Olivares, the “1” in Chacon’s record thanks to the ninth-round TKO he scored in June 1973. Chacon entered the fight as a 2-to-1 favorite, not just because he was an exciting young champion, but also because the 28-year-old Olivares was viewed as being past his prime. Although his record was a sparkling 71-3-1 (63), he was just two fights removed from a 13th-round KO loss against Alexis Arguello, Chacon’s WBA titular counterpart. The anticipated storyline was obvious: An exciting young lion seeking to further enhance his star power by beating the old lion as well as avenging his only defeat to date.

Unfortunately for Chacon, it didn’t turn out that way.

For reasons only known to Chacon, he fell into the party life and that life caused his weight to soar. Two weeks before the match he scaled 14 pounds above the 126-pound championship limit, and because of that he was forced to employ extraordinary measures to shed the weight. According to reports, Chacon’s back was whipped with eucalyptus leaves in order to open his pores as much as possible before his sauna sessions.

The good news was that he made weight. The bad news was that Chacon badly overshot the target as he scaled a bony 124½. Conversely, Olivares – renowned for his own party-hearty lifestyle – scaled a perfectly conditioned 125¼. Despite fulfilling his obligation on the scale, Chacon looked to be in no condition to fight, but because this was the era of same-day weigh-ins, Chacon had no choice but to fight.

Once the bout began, it was clear Chacon had nothing and Olivares had everything. Chacon’s punches lacked speed and snap, and his movements were slow and forced while Olivares moved nimbly and punched powerfully. Following a feeling-out first, Olivares shook Chacon with a compact left uppercut to the jaw early in round two, then drew the champion into a toe-to-toe exchange. An overhand right wobbled Chacon and a follow-up hook-right scored the first knockdown. Chacon rose at referee Larry Rozadilla’s count of eight but the man nicknamed “Mr. Knockout” proved to be too much. Olivares swarmed the weight-weakened warrior and floored him a second time with a volley of power shots. Chacon arose once again and tried his best to fire back. His effort proved futile in the face of Olivares’ follow-up assault, an assault that prompted Rozadilla to stop the fight at the 2:29 mark.

Just like that, Chacon was a former champion, and his feeble performance vaporized the visions of stardom that were so vivid just nine months earlier. Not only was Chacon defeated, he was humiliated. But while some fighters would have slunk away in shame, Chacon, now fully aware of how much he had squandered by losing the championship in the manner he did, made a promise to himself: I will become world champion again. Little did he know how much he had to give – and give up – in order to turn that promise into a reality.

Two fights into his quest, Chacon traveled to Mexicali to meet an obscure Mexican brawler named Rafael “Bazooka” Limon, who came into the fight with an unglamorous 20-7 (16) record. Just two fights earlier, Limon lost a 10-round decision to previous victim Victor Ramirez and just 22 days before facing Chacon he pounded out a 10-round decision win over 8-3-1 journeyman Juan Pablo Oropeza. Limon was a rough, tough and gritty body puncher prone to bending the rules as well as suffering cuts around the eyes. On paper he presented little threat to the world-rated Chacon, but on the night of December 7, 1975 he rose far above his station. He swelled Chacon’s face, won seven of the 10 rounds and left the ring with a stunning 10-round unanimous decision victory that earned him instant international respect. For Chacon, it was his second loss in his last three fights, and once again he was forced to pick up the pieces.

This he did. He won 14 of his next 15 fights – including a 10-round decision over Olivares in August 1977 to close out their trilogy – to set the stage for a rematch with Limon on April 9, 1979. This meeting took place on Chacon’s turf: The Sports Arena in Los Angeles. Chacon built a substantial lead by dominating rounds four through six, cutting Limon over the right eye in the fifth. The frustrated Limon was warned for thumbing in the sixth, and his angst was deepened when an accidental butt worsened the existing eye cut to the point that the fight had to be stopped. Under today’s rules, Chacon would have been declared the technical decision winner because he was ahead on all scorecards (60-56, 59-56 twice), but because this was 1979 the official result was a technical draw.

Despite suffering his second blemish against Limon, Chacon earned his first opportunity to complete his mission on November 16, 1979 at the Forum in Inglewood, Calif. His opponent: WBC super featherweight champion Alexis Arguello, who was making the sixth defense of the belt he won from Alfredo Escalera in January 1978 and who was fresh off a butt-marred 11th round TKO victory against Limon in July 1979. Chacon boxed sharply in the early rounds and even stunned the champion in round four with a pair of looping rights. In round six, however, Arguello found his groove as he hammered Chacon and opened a two-inch gash on the corner of the challenger’s right eye. The battering continued through the seventh until the ringside physician examined Chacon’s cut eye and stopped the bout between rounds seven and eight.

Four months after the TKO defeat against Arguello, Chacon and Limon met for the third time on March 21, 1980. The site was the Forum in Inglewood, Calif., and though the official result was a split decision for Chacon, most observers believed Limon had done more than enough to earn the victory, especially since he scored the fight’s only knockdown in round seven. Despite the disagreeable result, the series now stood at 1-1-1.

According to an article written by The Fight City’s Michael Carbert last year, this fight had a profound effect on Valorie Chacon, Bobby’s wife since 1971. According to Carbert, Valorie spent the evening of the fight with friends at a local bar and during the evening TV newscast, the station flashed separate “after” photos of the boxers.

“First the loser,” upon which Limon’s relatively unmarked face was shown. “And now, believe it or not, the winner!” The sight of her husband’s cut and bruised face horrified Valorie to the point that she went home and pleaded for her husband to retire. Of course, he would not.

After scoring victories against Roberto Garcia (KO 10) and Leon Smith (KO 3), Chacon earned his second chance to become a world champion when he faced WBC super featherweight king Cornelius Boza-Edwards May 30, 1981 at the Showboat Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas. Just like his first title shot against Arguello, Chacon performed well in the early rounds but Boza’s youth, strength and firepower eventually eroded the 29-year-old challenger’s gas tank to the point that he took a battering in the final three rounds. At the request of Chacon’s manager, referee Carlos Padilla stopped the fight between rounds 13 and 14.

The arguments between Bobby and Valorie continued to escalate, but the fighter, still believing he could secure one final shot at a championship, continued to fight as he stopped Agustin Rivera in November 1981 and Renan Marota in February 1982. During the month of the Marota bout, Valorie attempted to force the issue. One account had her flying to Hawaii with this plan in mind: Secure jobs for both of them, return to California to persuade Bobby to quit boxing, and, once he did, begin the next phase of their lives. Although she found a job for herself, she was unable to convince her husband to join her, so she ended up flying back to California.

According to Ralph Wiley’s book “Serenity: A Boxing Memoir,” Valorie tried to end her life shortly before Chacon’s bout against Morata by ingesting a handful of sleeping pills. She was found in time to save her life, but after she woke up in the hospital, Bobby told Wiley that “she ripped the tubes out of her arm and walked out. She disappeared. She was missing for nearly a month. They found her wandering around the Sacramento airport. She was talking about guns.”

On March 15, 1983 – one day before Chacon’s scheduled 10-rounder against Salvador Ugalde at the Memorial Auditorium in Sacramento – Valorie had finally reached her breaking point. She picked up the .22 rifle the couple kept in the bedroom, pointed the barrel at her head and pulled the trigger.

Her suicide might have ended her earthly torment, but Chacon’s was just beginning. He was now a widower and a single father of three and he was hours away from stepping into the ring. Distraught and racked with guilt, Chacon still decided to fight on, and with Valorie’s father and brother in his corner, he told Wiley he “tried to kill Ugalde.” Fortunately, Chacon just scored a third-round TKO, and after the fight, he dedicated his victory to Valorie.

Meanwhile, Limon had recovered nicely from his failed challenge of Arguello and his “loss” to Chacon. Not only did he become a world champion, he did so twice. After beating Frank Ahumada (W 10) and Frankie Baltazar (KO 4), he won the WBC super featherweight championship vacated by Arguello by stopping Idelfonso Bethelmy in the 15th round December 11, 1980 at the Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles. Limon lost the belt in his first defense to Boza-Edwards by unanimous decision less than three months later, but regained the WBC title in May 1982 after stopping Boza-Edwards’ successor Rolando Navarrete in the 12th round of an underrated classic. It was at this point that Limon agreed to defend his championship against his old rival Chacon, who had added victories against Rosendo Ramirez (KO 8) and previous conqueror Arturo Leon (W 10) since dispatching Ugalde.

In the February 1983 issue of KO magazine, Limon was described by future Hall of Famer Steve Farhood as “the best bad fighter in boxing” because of his looping, clubbing arm punches, his lack of hand or foot speed, and his vulnerability to cuts. Hall of Fame matchmaker Don Chargin said this of Limon’s title-regaining victory against Navarrete: “I’ve never in all my years in boxing seen a guy get beat up for so long and manage to come back and score a sudden knockout. Limon literally used his head to win. Navarrete beat on it so often he got tired. Limon may be the only fighter in the world who beats fighters by allowing them to hit him.”

Limon’s intangibles more than made up for his technical shortcomings, and his willingness to dish out and endure sustained punishment is even more amazing in light of what Limon told Farhood concerning his true feelings about “The Sweet Science.”

“I hate it,” he declared. “It’s awful. You can go blind. You can get killed. You can lose your marbles. The only reason I do it is for the money. Fighting is what I do for a living. It’s all I know.”

Those feelings surely were exacerbated during a 10-month, 41-5 amateur career in which he accidentally killed an opponent, an event that prompted him to swear off street fighting. Because he didn’t take up boxing until age 15 – and because he remained a work in progress upon turning pro at 17 in December 1972 – Limon lost five of his first 13 fights. Once he found his unique groove – a blend of tenacity, toughness, incredible stamina and a rock-solid chin – he became a handful for the world’s best fighters, including Chacon.

The scene for their fourth and final meeting was Sacramento’s Memorial Auditorium, the site of Chacon’s last four fights. The amped-up crowd that would repeatedly chant “BOB-BEE! BOB-BEE!” during the main event also witnessed the U.S. debut of a rising young star named Julio Cesar Chavez, who upped his record to 34-0 (28) at the expense of Jerry Lewis, an opponent Chavez stopped in five rounds in Tijuana 49 days earlier. For the record, Lewis was disqualified in round six for repeatedly spitting out his mouthpiece.

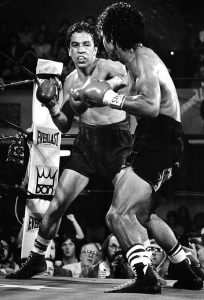

Limon vs. Bobby Chacon (left). Image courtesy of the World Boxing Council

Limon was installed as a solid 3½-to-1 favorite and in the first three rounds he validated those odds by working behind a stiff southpaw jab and unexpectedly compact power shots to the head and body. In round two, Limon drove Chacon to a corner pad and whaled away with an extended assortment of hooks, uppercuts and overhand blows. Too proud to clinch, Chacon did his best to weather the storm. He used his arms to block as many punches as possible while weaving his upper body away from others. Just when it appeared that Chacon would be overwhelmed, he lashed out with several lead rights and drove Limon back to ring center. This scenario was repeated at least a half-dozen times in the bout; it was almost as if Chacon’s tumultuous life outside the ring was being played out inside it as he was constantly challenged by crises that he was forced to confront.

With 20 seconds remaining in the third, Limon punctuated his early dominance by dropping Chacon with a chopping counter left that almost pushed the challenger to the canvas. In the closing stages of round four, a hard clash of heads opened a cut on the bridge of Chacon’s nose near the right eye. Despite the early setbacks, Chacon continued to resist with all his strength as he nailed the champion with enough right hands down the middle to raise a swelling underneath Limon’s left eye.

After his shaky start, Chacon began chipping away at Limon’s lead. He started moving better. He began and ended most of the exchanges. His combinations were delivered with more fluidity. And, as a result, he made the case that he could still win. After all, this fight was one of the WBC’s final 15-round championship fights, and because of that there was still ample time for Chacon to erase his early deficit.

Chacon (L) is about to launch a right hand at Limon during the WBC 130-pound title fight at the Memorial Auditorium on December 11, 1982 in Sacramento, California. Photo: The Ring Magazine via Getty Images

A key moment occurred midway through the seventh as Limon landed a rocket-like left to Chacon’s chin, then drove the challenger to the neutral corner pad with a series of ripping blows. Instead of languishing in the corner, Chacon struck back and forced the champion to break off the exchange, the first time he made the leather-tough Limon “blink.” Shortly thereafter, Chacon backed Limon to the ropes and blasted in his own combinations, showing that he could bully the bully.

Limon again muscled Chacon to the ropes midway through the ninth and initiated a wild exchange, but a huge lead right by Chacon made the champion retreat immediately on badly stricken legs. He reached out with both arms to grab Chacon while the challenger pasted Limon again and again with the right. Limon’s bloody mouthpiece hung precariously on his lips and Chacon nearly put him on the canvas. As Chacon fired away, the heavily partisan crowd was roaring at full volume, hoping that their collective will would drive their man to levels even he couldn’t have reached on his own.

Chacon’s dominance in the middle rounds cut deeply into Limon’s early lead, but the champion was a proud man who was determined to keep his precious title. In the 10th, he turned the fight back his way by uncorking a dynamite left cross that drove Chacon to the floor for the second time. Chacon was up immediately, and though Limon pushed hard to end the fight the challenger was able to navigate his way out of the round.

As the fight rolled into the “championship rounds” of 11 through 15, Chacon knew he was treading into territory that favored Limon’s remarkable stamina. Chacon was more than equal to the task as he traded punch for punch with no letup and no compromise. Whenever Limon backed Chacon across the ring with a withering series of power shots, Chacon responded with trip-hammer rights that shook Limon to his core. At one point in the 13th, they simultaneously staggered each other, but Limon was left in worse shape as Chacon’s right nailed Limon a split-second sooner than Limon’s left cross. Limon was almost defenseless in the round’s final 30 seconds but after the bell sounded Chacon showed how much stress he was under as he began to walk toward to wrong corner before trainer Joe Ponce guided him toward the correct one.

Despite the tremendous punishment they dished out to this point, the pace actually escalated toward almost inhuman levels as they neared the finish line. Through they entered the ring with hostility in their hearts, their mutually satisfied thirst for combat transformed that hatred into respect. As the bell sounded for the final round, Chacon even reached over referee Isaac Herrera’s shoulder just so he could touch gloves with Limon.

Entering the final round, the judges’ math presented yet another formidable mountain for Chacon to climb. Not only did he have to win the 15th round, he had to score a knockdown in order to avoid a draw. With just 15 seconds remaining in the bout, Chacon scored that knockdown thanks to a pair of right hands that sent Limon almost flying across the ring before landing heavily on his left side near the ropes. It took every bit of Limon’s courage to regain his feet at Herrera’s count of seven, and while his face wore a sickening half-smile, his expression was also a portrait of bravery and defiance. He would not allow Chacon the satisfaction of stopping him before the final bell, which struggled to be heard above the deafening din of a wildly rapturous arm-waving throng.

Bobby Chacon celebrates in the ring, wearing his WBC belt after winning his fourth showdown with rival Rafael Limon in epic fashion. Photo: The Ring Magazine via Getty Images

The fight over, the two rivals warmly embraced, satisfied they did all they could to make their case to the judges. In the end, that knockdown – along with Tamotsu Tomihara’s extraordinary decision to award Chacon a 10-7 score instead of the customary 10-8 – resulted in scores of 143-141 (Carlos Padilla), 142-141 (Angel Luis Guzman) and 141-140 (Tomihara) for the winner and new WBC super featherweight champion.

At long last, Chacon had regained what he had lost nearly seven-and-a-half years earlier. He paid a steep physical, emotional and spiritual price to complete his quest, and though his record now read 51-6-1 (42), the rejuvenated 31-year-old Chacon probably felt a lot like his 22-year-old self – at least in that moment.

“Bazooka made a mistake; he came to my hometown,” Chacon told Keith Jackson, who called the bout for ABC. “I did the scoring and they (the crowd) did the punching. I got in shape and I’m 31 years old. How can a person this old throw so many punches? I was 22 years old and I threw it away. I had to get it again. This is dedicated to my wife; she couldn’t wait for me.”

Then he paid tribute to his valiant opponent.

“Bazooka and me fought three times, and he has gotten better, no doubt,” he said. “His heart has grown; he’s fought some good fighters. I hit him like that before and he was looking for a hiding place. I hit him like that tonight and he didn’t care. He was coming right back. He shook it off and came back.”

“Chacon has a great heart,” Limon’s manager Ricardo Maldonado told The Ring’s Christopher Coats as he tapped his chest. Then he tapped on his leg and observed “his legs are pretty good too, for a 31-year-old fighter. Chacon is a great fighter…and a brave one.”

As is often the case, the brutality expended in the ring served to eradicate all previous ill feelings. In a 2018 “Best I Faced” interview conducted by RingTV.com’s Anson Wainwright, the 64-year-old Limon revealed that he and Chacon became good friends after both men retired.

“I remember him with a lot of joy, a lot of love and affection,” he said.

For the record, he said that Chacon had the best defense of any opponent he fought as well as being the best puncher.

“Chacon was like an armadillo; he was covering everywhere,” he said. “You had to make some feints to throw a punch and land it fast because he had a really nice defense.” As for his punching ability, “he was a mad dog! Maybe it was because he was addicted to drugs, but all four fights with him were dog fights.”

Chacon consolidated his Fight of the Year win over Limon in 1982 with a Fight of the Year win over Boza-Edwards in 1983. But Chacon’s epic late-career revival ended in Reno, Nevada on January 14, 1984 at the hands of WBA lightweight champion Ray “Boom Boom” Mancini, who dished out such intense punishment that referee Richard Steele stopped the bout shortly before the midway point of round three. Although Chacon won his final seven fights and finished his career in June 1988 with a mark of 59-7-1 (47), it was clear that the physical toll from his many wars was considerable. He suffered from dementia and died at age 64 in September 2016 after falling while in hospice care.

Limon, too, experienced a long decline following the loss to Chacon. The far younger and speedier Hector Camacho won the WBC title stripped from Chacon after defending against Boza-Edwards instead of Camacho by scoring a fifth-round TKO in August 1983. From there, Limon lost far more than he won, and several of his conquerors boasted notable names: Oscar Bejines (KO by 4), Julio Cesar Chavez (KO by 7), Rolando Navarrete (L 10) and Sharmba Mitchell (L 8), whose trunks Limon infamously pulled down during the March 1990 fight that was aired on USA Network. Limon retired with a 53-23-2 (38) record following a seventh-round stoppage against John Armijo in September 1994. According to Wainwright’s story, Limon served in the Mexican army for 30 years before retiring from active duty in the late 1990s.

“The army taught me to be a gentleman, to take care of myself, my image, presentation, my timekeeping and discipline,” Limon, who suffered a stroke in 2017 but was doing well at the time he talked with Wainwright, said. “I appreciate that. I have never drank (or) done drugs. I used to like the women; that was my weakness (laughs). Now I only have my wife.”

I have seen many great fights in my nearly 49 years as a boxing fan, but when one combines the tremendous two-way action with the incredibly dramatic last-second fulfillment of a multi-year journey that included a traumatic family tragedy, Chacon-Limon IV not only remains the greatest boxing match I’ve ever seen, it may well be the greatest boxing match that I will ever see.

***

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, West Virginia. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 21 writing awards, including two first-place awards, since 2006. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. as well as a panelist on “In This Corner: The Podcast” on FITE.TV. He is the author of “Tales from the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics” (available on Amazon) and the co-author of “Muhammad Ali: By the Numbers” (also available on Amazon). To contact Groves use the email [email protected] or send him a message via Facebook and Twitter (@leegrovesboxing).