Larry Holmes: Overworked and underpaid assassin

Editor’s Note: This feature originally appeared in the Larry Holmes Special Issue, which is available for purchase at The Ring Shop.

“The Easton Assassin” lurked in the shadows for a very long time.

There was no podium moment in the amateurs. There was no “Star-Spangled Banner” or ticker tape parade through his home city. There was no rich syndicate looking to invest in his professional career. There was no TV network knocking down the door to broadcast his fights. There were no advertising deals or endorsements.

Unlike Floyd Patterson, Muhammad Ali, Joe Frazier and George Foreman – legendary heavyweight champions who had claimed Olympic gold for the United States – Holmes rose through the ranks in relative obscurity. During the embryonic stages of his career, the future Hall of Famer was overworked and underpaid, barely able to cover the cost of fuel required to get him from one seedy venue to the next.

“I was struggling because I didn’t have no money,” Holmes told me in a recent interview for The Ring. “I’d have a fight in Scranton [Pennsylvania] and make 150 [or] 200 dollars. It’s a case of take it or don’t take it. If you don’t take it you don’t fight, so I took it. I’d put gas in my car, drive up there, and it was neat for me because I was fighting and winning. Back then, people told me that I was going to end up punchy or crazy. People would tell me I was going to get the shit beat out of me. All these years later, do I sound punchy?”

The question is rhetorical. Holmes knows that he doesn’t sound punchy. After 29 years in professional boxing (March 1973 to July 2002), he’d posted a final career mark of 69-6 (44 KOs), with 21 of those victories coming in world title fights, and exited the sport in very good health. He made a fortune, achieved things beyond his wildest dreams. But what convinced him to ignore all those early detractors and stay the course?

“I was training in New York and met guys by the name of Wendall Bailey, Wendell Newton, Jasper Evans and Randy Neumann,” recalled Holmes. “I boxed those guys – they were pro long before I started – and I was doing good with them.

“I kept going and I thought my style worked well for me. I wasn’t thinking about the championship back then. It was all about getting in shape. But pretty soon I realized that I had some talent. I won the Golden Gloves, then I fought Duane Bobick [in an Olympic box-off] and he beat me. But I didn’t stop and I turned pro.”

“Back then, people told me that I was going to end up punchy or crazy. People would tell me I was going to get the shit beat out of me.”

The Bobick setback hurt Holmes’ reputation badly. The bout was broadcast live on national TV (ABC); Holmes had been disqualified for holding and subsequently lost out on an opportunity to represent the U.S. at the 1972 Munich Olympics. Some labeled him “a quitter,” but there were others who knew better.

Holmes had been introduced to the sport in his home city of Easton by former pro middleweight Ernie Butler, who worked as a guard in a county jail and taught boxing in his spare time. Butler saw something in the youngster and spent a lot of time with him. He taught Holmes the basics, nurtured him as an amateur, then introduced him to the most famous fighter in the world.

Muhammad Ali was training for an upcoming exhibition in nearby Reading, Pennsylvania, and after observing the speed of Holmes’ fists, “The Greatest” hired him as a sparring partner. Being relatively close to the Philadelphia area, Holmes would also make his way to 2917 N. Broad Street to spar then-heavyweight champion “Smokin’” Joe Frazier.

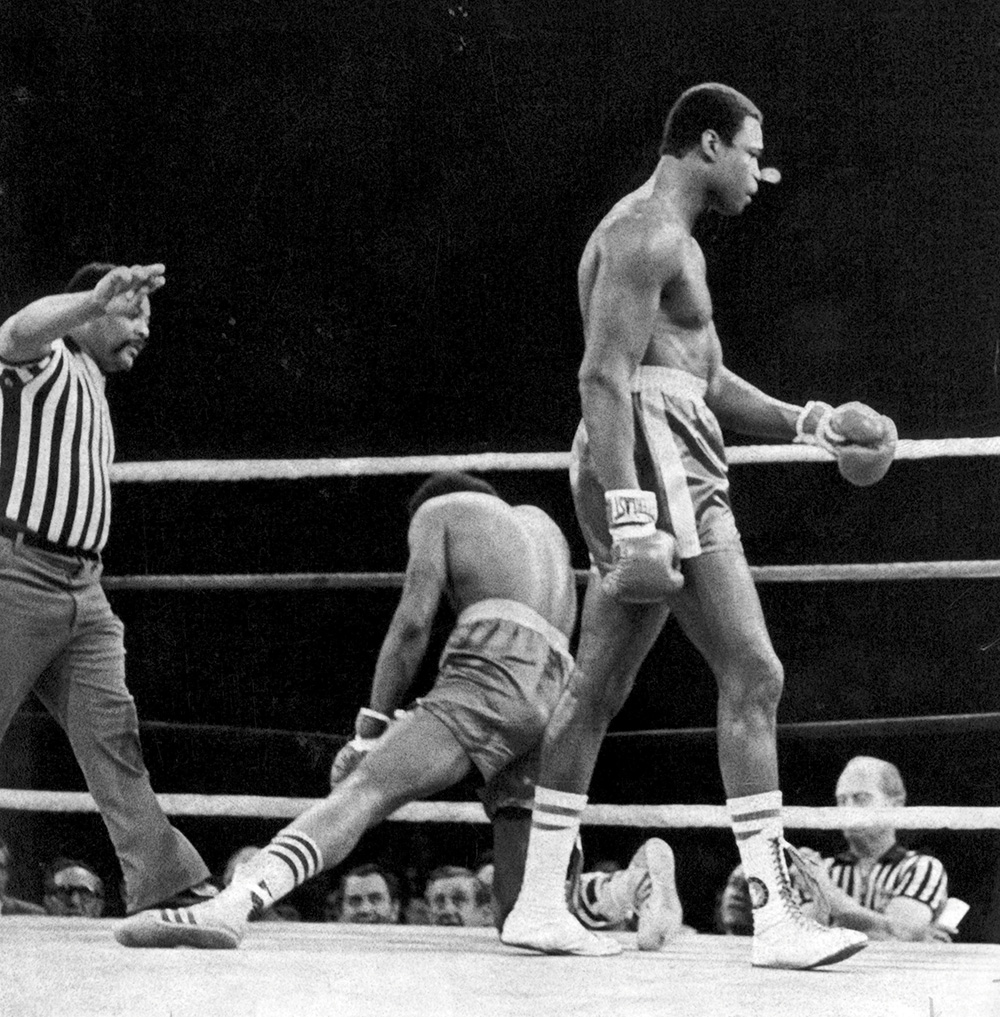

A sparse crowd in Cleveland looks on as Holmes (right) battles Kevin Isaac in 1973.

While Holmes was earning pennies as a professional fighter ($800 for eight fights in one year, according to the ex-champ), the education he was receiving courtesy of the glamour division’s top two professors was invaluable. Who the hell needs Olympic schooling when you’re at university with Ali and Frazier? Holmes was also growing physically. He’d been barely 190 pounds for Bobick and was now comfortably over 200 pounds as a heavyweight prospect.

Early on, promoter Don King had entered into a 50-50 managerial partnership with Butler, but quickly sought a complete takeover when Holmes showed some promise. In typical King fashion, he succeeded in pushing Butler out and quickly enlisted the services of volatile coach Richie Giachetti, who remained with Holmes for the majority of his championship career and beyond. The pair enjoyed incredible success, but there were periods when Eddie Futch and Ray Arcel – often accompanied by Freddie Brown – took the reins.

“I never split from Richie,” interrupted Holmes in a bid to clear the air. “I never left Richie. I was with Eddie [Futch] because that’s what Don King wanted, but I never left Richie.

“Richie shows you how to fight. His style will work for you if you want to learn. If you listen to him, he’ll tell you: Do this, do that, stay away from this, stay away from that – normal shit. But I did it and he stuck with me. And when I started making some money, he got a percentage. He took 25 percent, but he was a good guy. He was a good guy until the day he died.”

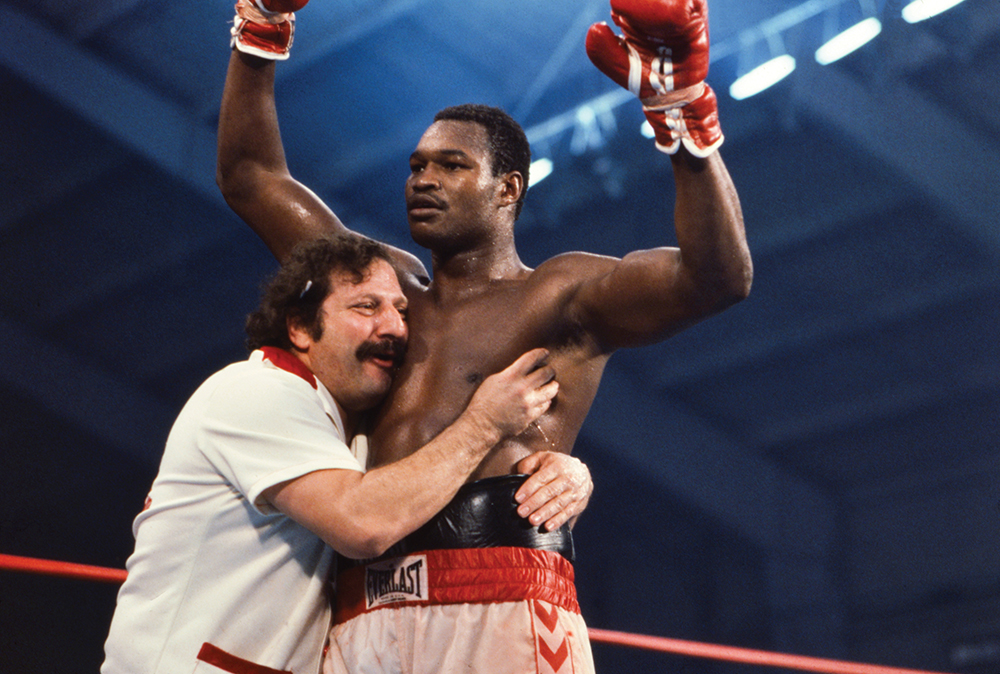

Nobody believed in Larry Holmes more than his longtime trainer, Richie Giachetti. Photo by Manny Millan /Sports Illustrated/Getty Images

Despite his obvious respect for Giachetti, Holmes has always been quick to show his appreciation for the old school legends who helped him forge a very special legacy. “Arcel, Brown and Futch, in my opinion, were the best boxing trainers ever,” Holmes told me in 2011. “They had over 100 years of boxing experience combined. When you have guys like that in your corner, how can you lose? These guys taught you how to fight, whereas today there are trainers who are barely out of high school, learning from books. You don’t learn anything that way. You need to draw on real experiences, and it’s too bad that fighters today don’t have that.”

By March 1975, Ali was in his second reign as heavyweight champion and preparing for a title defense against Chuck Wepner. It would mark the last time that Holmes would serve as sparring partner for his friend and mentor. With training complete, he bid the champion farewell and scored a first-round knockout of journeyman Charley Green on the Ali-Wepner undercard. Ali halted Wepner in the 15th and final round.

Holmes dispatched Charlie Green in one round in Richfield, Ohio in 1975.

Later that year, Ali ventured to Manila for a rubber match with archrival Frazier. What became arguably the finest heavyweight championship fight of all time, “The Thrilla in Manila,” was supported by Holmes’ first significant step up in class. He was matched with the 34-5 Rodney Bobick, younger brother of his Olympic box-off conqueror, and “The Easton Assassin” rose to the occasion with an impressive sixth-round stoppage.

“I had a good time in Manila,” recalled Holmes. “It was my first time going that far away on an airplane. It was a good time for me, but nobody thought I was going to win. Rodney Bobick was a better fighter than his brother; he could box and he could fight. But I liked the way he was boxing, because I could counter whatever he was doing. He’d jab and I’d put a right hand over the jab.

“I was ringside for Ali-Frazier 3. I was right there. Everything was ‘Ali! Ali! Ali!’ And I was like everybody else: ‘Ali! Ali! Ali!’ (laughs) Ali was more of a friend to me than Joe Frazier. But Ali did say to me, ‘What does Joe do when you do this? What does Joe do when you do that?’ I’m like, ‘Man, I can’t tell you that!’”

After disposing of Bobick, Holmes knocked out his next four opponents before taking another step up in class. Roy Williams was 238 pounds, 6-foot-5 and had a record of 23-4 (18 KOs). He was an authentic knockout artist from Philadelphia who Holmes knew only too well.

Williams had also served as a sparring partner for Ali in the early ’70s. But while Holmes had grown to love and respect his idol, Williams had very little time for the self-styled GOAT, and that showed every time they shared a ring together.

When promoter Don King saw potential in Holmes, he was all in.

“Ali didn’t want to box him,” revealed Holmes. “Ali wanted somebody to take it easy, but Roy said, ‘No, I’m fighting! I’m gonna beat your ass! I’m gonna kick your ass!’ Every time he got in the ring with Ali, he’d try and beat him up. They didn’t want that kind of fight with Roy, because it was like that every day. Ali would maybe use Roy for one round, two at the most.

“Roy was a big puncher and he didn’t like Ali. He was supposed to fight [on the Foreman-Ali undercard], and something happened. Roy didn’t get to fight. Later, he wanted Ali to pay him the money he’d lost. Roy was telling me, ‘I’m gonna kill him! I’m gonna knock his ass out!’”

In what was the closest fight of his pre-championship career, Holmes scored a 10-round unanimous decision over Williams in Landover, Maryland, on April 30, 1976. The main event that night saw Jimmy Young lose a narrow – many say controversial – decision to Ali. The great champion was now in decline and Holmes was improving with each and every fight.

Young was also a serious player in the heavyweight division at that point. Seven months after pushing Ali to the limit, he outpointed powerful slugger Ron Lyle for a second time. His reward was a shot at former champion George Foreman in San Juan, Puerto Rico, on March 17, 1977. Holmes scored a fifth-round stoppage of Horace Robinson on the undercard and Young upset Foreman, sending the soon-to-be preacher into a decade-long retirement.

“George didn’t have nothing to do with nobody back then,” said Holmes, who would never fight Foreman. “You’d be like, ‘Hi George. How you doin‘?’ and he’d just say, ‘Hi. How you doin‘?’ and keep walking. We were in the same hotel, but we didn’t really talk, because George wouldn’t let you talk. But I still bragged about being around George. I bragged about being with Ali. I bragged about being around Joe Frazier.

“I thought Jimmy would win the fight with George. I was over there with Jimmy because he was my friend. I used to go down and visit him at his house. I used to meet him down at Joe Frazier’s gym. He was underrated for a long time. And I thought he beat Ali, but they didn’t give it to him.”

Now rated within The Ring’s top 10 heavyweights, Holmes was eyeing a world title shot. Following his victory in San Juan, the unbeaten contender scored consecutive knockout wins over Fred Houpe and Ibar Arrington in Las Vegas before being matched with another familiar face in a WBC heavyweight title eliminator.

Fred Askew was victim No. 21 for Holmes, who halted the Memphis-born journeyman in two.

During his days as a sparring partner, Holmes had accepted good money to work with Earnie Shavers, who was then world-rated. With 52 KOs in 54 wins, against six losses and one draw, Shavers had the highest knockout ratio among the division’s top contenders. Holmes had watched his former employer knock sparring partners out cold with 20-ounce gloves on.

However, since that time, Holmes was the one who had done all the improving. There were no secrets with Shavers and, at this point, all he had was a puncher’s chance against a brilliant boxer-mover who was closing in on his prime. The pair met at the Caesars Palace Sports Pavilion on March 25, 1978.

“I knew I could beat Earnie,” Holmes told me in 2020. “I knew he’d run out of stamina after four or five rounds, so I just had to box him. It was my first 12-rounder. I fought at my own pace and I didn’t want to get myself involved in a war. You don’t fight against a guy like that. Box, box, box. I gotta win, so I outboxed him, because he was strong and he was always ready to go.

“I’d sparred Earnie and knew how big a puncher he was. He was another guy that I didn’t wanna fight, but I had to fight him if I wanted a title shot. For four or five rounds against Earnie, you’re in trouble, so you need to box and stay away from him. That’s the only way to win.”

With Shavers essentially shut out over 12 rounds, Holmes was now in position to fight for the championship. He’d sparred Ali and Frazier. He’d been around George Foreman. The only elite-level heavyweight of the time that Holmes was yet to encounter was Ken Norton.

Tom Gray is managing editor for The Ring. Follow him on Twitter: @Tom_Gray_Boxing.