Wilfred Benitez vs. Roberto Duran 40 years later: El Radar detects Hands of Stone

Boxing has always cherished its oldies-but-goodies, which partly explains why so many fight fans fondly recall the feats of senior citizens of the ring who pushed back against advancing age to defeat Father Time as much as they did significantly younger opponents. The oldest fighter ever to win a widely recognized world title? Hey, almost everyone, even more recent devotees of the sweet science, know the correct answer is Bernard Hopkins, who was 48 when he wrested the IBF light heavyweight title from Tavoris Cloud on March 9, 2013. George Foreman, then 45, defied the natural laws of diminishing returns by winning the WBA and IBF heavyweight belts on a 10th-round knockout of Michael Moorer on Nov. 5, 1994, and the beloved “Old Mongoose,” Archie Moore, was 47 when he won the fringe New York State Athletic Association version of the world light heavy title, also then recognized by California and Massachusetts, on a 15-round points nod over Giulio Rinaldi on June 10, 1961.

There are, of course, corresponding tales of youthful phenoms who earned widespread acclaim by seizing world titles from far-more-experienced champions. Mike Tyson was just 20 when he became the youngest heavyweight ruler by stopping WBC titlist Trevor Berbick in two rounds on Nov. 23, 1986, in the process displacing Floyd Patterson, who was 21 when he won the title vacated by Rocky Marciano with a fifth-round TKO of nearly 43-year-old Archie Moore. Canelo Alvarez is considered by many to be today’s top pound-for-pound fighter, but Alvarez, who began punching for pay at 15, had logged 36 pro bouts when he won his first world title, the vacant WBC junior middleweight strap, on a 12-round UD over Matthew Hatton on March 5, 2011.

But the whizziest of boxing’s whiz kids is Puerto Rico’s Wilfred Benitez, a Puerto Rican prodigy who turned pro at 15 and shot to early prominence like a Cape Canaveral rocket launch. Benitez remains the youngest fighter ever to win a world championship, a distinction that perhaps is beyond being matched, much less exceeded. He was a mere 17 years of age when, stepping inside the ropes with a 25-0 record that included 17 victories inside the distance, he dethroned 30-year-old Colombian veteran (and future Hall of Famer) Antonio Cervantes via 15-round split decision for the WBA light welterweight title on March 6, 1976. Cervantes, who had made 10 successful defenses, came in with a 50-9-1 mark that included 27 wins by KO, but he had few answers for the array of skills exhibited by a wise-beyond-his-years kid who boxed masterfully, hit hard and accurately, and was not at all intimidated by the older man’s vast experience and imposing reputation.

Photo by The Ring Magazine/ Getty Images

Today marks the 40th anniversary of what arguably is the greatest victory posted by Benitez, known as El Radar for the pinpoint precision of his punches. The date was Jan. 30, 1982, and Benitez, still only 23, came in as the reigning WBC junior middleweight titleholder, his third championship in as many weight classes, and with a 43-1-1 (29) record. He had also set marks as the youngest fighter to win two world titles (the second on a 15-round split decision over WBC and lineal welterweight champ Carlos Palomino, yet another future Hall of Famer) and then three (on a KO 12 of WBC 154-pound kingpin Maurice Hope on May 23, 1981). Even in his only defeat, a 15th-round TKO at the hands of Sugar Ray Leonard on Nov. 30, 1979, which cost him his WBC welterweight belt, Benitez had fought valiantly throughout, and impressively in spots.

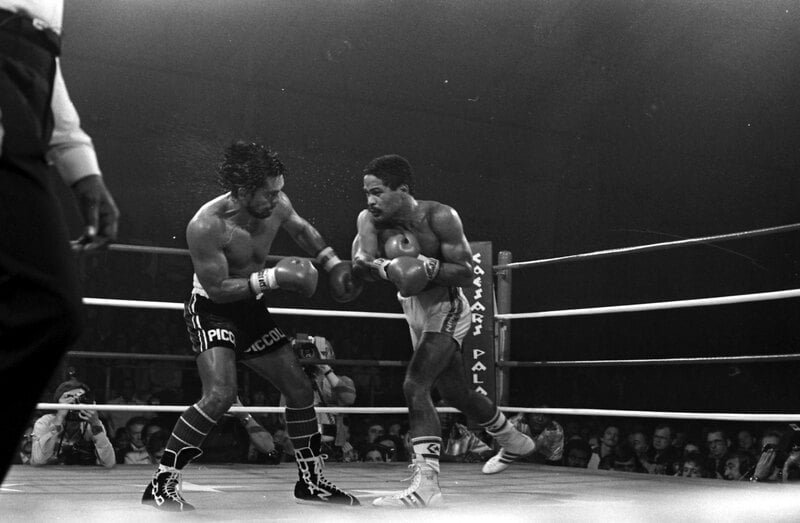

On this night, however, the guy in the other corner from Benitez at the Caesars Palace Sports Pavilion in Las Vegas was Panama’s Roberto Duran, the “Hands of Stone,” a 30-year-old living legend whose fearsome aura had been tarnished, but perhaps not irrevocably so, by his No Mas surrender against Leonard in the eighth round of their rematch on Nov. 25, 1980. Duran had won twice since that embarrassment, which he had attributed to stomach cramps (not everyone was buying his version of the story), a pair of 10-round decisions over Nino Gonzales and Luigi Munchillo, and he was hinting at retirement if he did not reveal himself to be the same ruthless and remorseless force of nature he had been in his victorious first matchup with Leonard. That Duran was then described by New York Times sports columnist Dave Anderson as “the noblest savage in boxing.”

Duran, at that point 74-2 (56), very publicly saw a victory over the younger (by seven years), taller (by 2½ inches) and longer-armed (three inches in reach) Benitez as the springboard to a rubber-match showdown with Leonard. He was so confident of success that he said, “If I lose (to Benitez), it’s over.”

“Right now my mind is on Benitez, not on Leonard,” Duran, not sounding terribly convincing, had said in the lead-up to the fight. “Everybody is concerned about the situation of me fighting Leonard. Nobody asks why Leonard is not giving me a rematch. But if I win, Leonard will have to come and ask me for a fight.”

Benitez also had similar visions of all the good stuff that might lie ahead if he were to add Duran to his list of victims. He was young, strong, tremendously accomplished and steadfast in his belief that he had all the necessary requirements for another move up in weight, for a challenge of middleweight champion Marvelous Marvin Hagler.

Common opponent Sugar Ray Leonard (pictured at the fight) confidently picked Benitez to win. Photo by The Ring Magazine/ Getty Images

But prefight talk is cheap, and at least one very interested observer – that would be Leonard, at ringside as an expert commentator for the HBO telecast – who predicted, “I see Benitez stopping Duran.”

Finally it was put up or shut up time, and by and by Benitez frustrated and infuriated Duran as he appeared to build a commanding lead on points. In the 15th round, during which Benitez fought with his back pressed against a corner turnbuckle yet was almost casually beating Duran to the punch, blow-by-blow announcer Barry Tompkins offered his take on what he was seeing. “Duran is now unable to score at all!” Tompkins said. “An uppercut, and a left hand (by Benitez)! The crowd comes alive! Benitez doing the damage! Benitez provides a moving target even when his back is in the corner!

“A right hand and a left throw by Benitez! Duran is on wobbly legs! Three left jabs! It is all Benitez here! It is all Benitez! The fight has been all Benitez! Benitez, virtually without question, is the winner of the fight!”

The three official scorecards, it was generally agreed afterward, were closer than the action had seemed to indicate, although Benitez came out ahead by margins of 145-141 (Lou Tabat), 144-141 (Dave Moretti) and 143-142 (Hal Miller) as determined by the three men with pencils. In keeping with his reputation for haughty defiance, Duran turned his back on Benitez and dismissed him with a wave of his right glove when the smiling champion, anticipating a favorable outcome, ventured toward him to offer a conciliatory hug before ring announcer Chuck Hull read the judges’ tallies.

All that remained was for the postscripts, more than a few of which were predictions that Duran, as magnificent as he once had been, had now been rendered a memento of the past to be stashed into boxing’s dusty bin of what used to be but no longer was. Even members of Team Duran were among those suggesting he take his leave from the ring wars while the going was good.

Ray Arcel, the 82-year-old encyclopedia of boxing who had just worked Duran’s corner, said, “His body just doesn’t respond anymore. Roberto’s only 30 but he’s been boxing 15 years. And the way he’s trained, or not trained, he’s been self-destructive. I always used to tell him, `Nobody can beat you, Roberto, nobody except for one man – Roberto Duran. You’re the only one who can beat you. And that’s the way it turned out. But he’s not any different than a lot of fighters who did the same thing to themselves.”

And this, from Carlos Eleta, Duran’s longtime manager: “I think I will retire him. The time has come.”

Photo by The Ring Magazine/ Getty Images

But age in boxing is a relative thing, and always has been. Some rare old men in boxing years, like Hopkins, Foreman and Moore, can cling to vestiges of their glorious primes with the tenacity of pit bulls; some young stars, seemingly poised for long residences in their sport’s penthouse, can find eviction is only one poor performance away. And so it was for both Benitez and Duran, a passing of the torch that got passed right back again.

The Duran who was supposed to just fade away following his come-uppance from Benitez? He logged 42 more bouts over the next 19 years, going 29-13 (15) and winning two more world titles few expected him to claim, bludgeoning WBA junior middleweight titleholder Davey Moore over eight rounds on June 16, 1983, and, at 37, outpointing WBC middleweight ruler Iran Barkley. More than a few boxing historians list Duran as one of the 10 greatest fighters of all time.

But the glow of Benitez’s taming of Duran proved to be not nearly as long-lasting. In his next ring appearance, on Dec. 3, 1982, the crown prince who would be king lost his WBC title on a 15-round majority decision to Thomas Hearns. That in and of itself would not normally be held too much against Benitez – Hearns is an all-time great – but the manner in which the belt was turned over was troubling in that the “Motor City Cobra” fought from the eighth round on with a damaged right hand, thus scuttling his most dangerous weapon.

Pat Putnam, writing for Sports Illustrated, described the handicapped Hearns’ triumph thusly: “Last Friday night, against Wilfred Benitez in New Orleans’ Superdome, Hearns finally showed that he brings more to boxing than a big bang. Fighting with only his left hand from the eighth round on after hurting the right on Benitez’s head, Hearns outboxed the master boxer and lifted the Puerto Rican’s WBC super welterweight championship on a majority decision.”

For whatever reason, the loss to Hearns signaled a professional and even more troubling personal slide for Benitez. He was just 9-6 throughout the remainder of his career, winning three times and losing just as often inside the distance. In his final bout, on Sept. 18, 1990, in Winnipeg, Manitoba – two days after his 32nd birthday – a clearly diminished Benitez was outpointed over 10 rounds by journeyman Scott Papasodora, who would lose his next three fights after that, two by KO, to finish 16-9-1.

The nadir came when Benitez traveled to Salta, Argentina, for a matchup with a capable Argentine, Carlos Herrera, on Nov. 28, 1986. Herrera stopped Benitez in seven rounds, but that was not the worst of it for a onetime wunderkind; one version of the story is that unscrupulous promoters absconded with Benitez’s purse and his passport, leaving him stranded on the streets and begging for handouts. Promoter Miguel Herrera insists Benitez was paid, albeit late, and that it was the fighter who refused to return home for nearly two years.

Whichever variation of the tale is the more accurate, Argentine journalist Jose Corpas wrote that an envoy representing the Puerto Rican government was dispatched to Argentina to bring the three-time former world champion back to his island homeland.

During his dizzying ascent to the top and stay there, while not as long as it might have been, Benitez was so highly regarded that he was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1996. But by then he had been diagnosed as having suffered severe brain damage and post-traumatic encephalitis, major medical issues exacerbated by the revelation that all of the money he had made in boxing was gone. His Puerto Rican home destroyed by Hurricane Maria in 2017, Benitez and his caregiver sister reside in an apartment building for low-income individuals and families in the hardscrabble west side of Chicago.

How good was Wilfred Benitez at his height of his powers? Good enough that some would rate him as equal to, or nearly so, Felix Trinidad as the greatest Puerto Rican fighter ever. Other suggest Benitez’s prime needed to be stretched out a bit more for him to enter that particular discussion.

READ THE MARCH ISSUE OF THE RING FOR FREE VIA THE NEW APP NOW. SUBSCRIBE NOW TO ACCESS MORE THAN 10 YEARS OF BACK ISSUES.