Manny Pacquiao: Sowing the Seeds

Editor’s Note: This feature originally appeared in the November 2020 issue of The Ring.

LIKE MANY FIGHTERS WHO GO ON TO ACHIEVE COLOSSAL SUCCESS, MANNY PACQUIAO CAME FROM VERY HUMBLE BEGINNINGS

There wasn’t much to suggest that this two-hour boat ride from Manila to Sablayan Island in January 1995 would be noteworthy at all. If not for one of the passengers, a 16-year-old named Manny Pacquiao, it would have been just another sojourn for young Filipino men traveling to receive a small purse to trade blows with other young men.

Once docked, the trip took another three hours by land to a small, covered basketball court. The malnourished Pacquiao weighed just 98 pounds for his fight and filled his pockets full of heavy objects (reportedly rocks and ball bearings) to make it to 106 pounds. Since he was under 18, he told the Games and Amusements Board that his birth certificate was back home in General Santos City and that he’d get it to them when he could.

The purse was just 1,000 pesos, equivalent then to $30, for Pacquiao to outpoint Edmund Ignacio over four rounds, but for a boy accustomed to drinking water for dinner because his mother didn’t have food for her five children, who slept on the streets after running away from home at age 14, and who sold donuts on the streets for a few pesos to stay alive, it was all the incentive he needed.

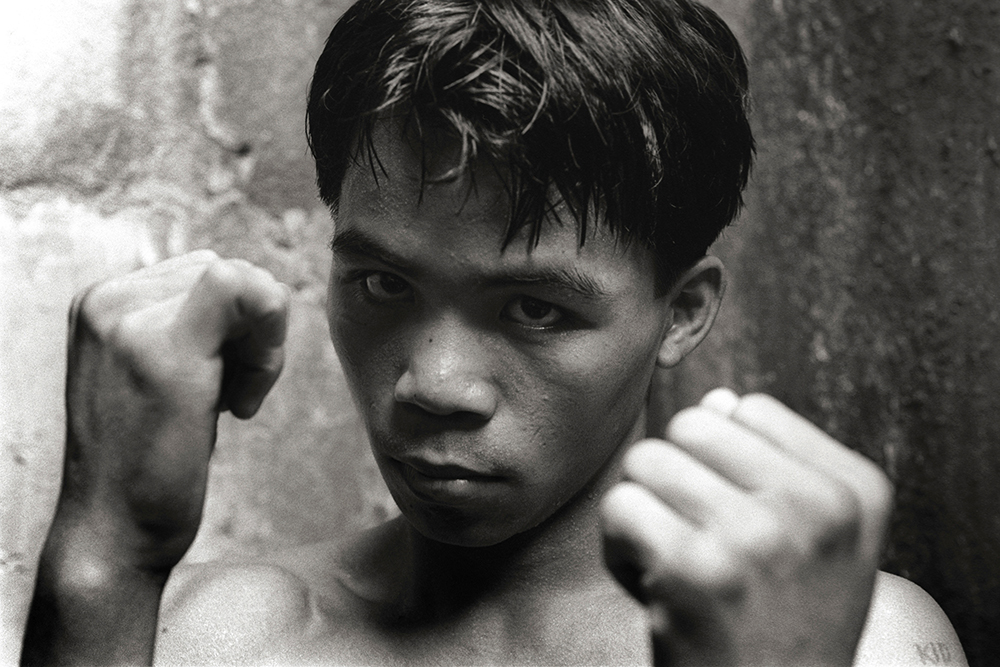

A teenage Pacquiao in Manila. (Photo by Gerhard Joren/LightRocket via Getty Images)

Long before he was flying across the Pacific for training camps in Hollywood, before Bob Dylan and Sylvester Stallone would drop by the Wild Card Boxing Club to watch him work out, Pacquiao would sweat away at the LM Gym on Paquita Street in Sampaloc. It sat on about 200 square meters of land, tucked in a labyrinth of narrow streets, before being torn down in 2009 (Pacquiao erected his “MP Tower” office and gym on the site). The equipment was worn out, the air smelled of urine from a wall near the ring that fighters used to relieve themselves, and yet this small gym was the training grounds for numerous world champions, including Luisito Espinosa, Morris East and Rolando Pascua. Pacquiao had been brought from General Santos City along with seven other boxers to the gym owned by Polding Correa, a well-off construction businessman from Malabon who managed boxers as a hobby. During the day, the boxers would work on the construction sites for Correa and then train in the afternoon. Pacquiao and the rest of his GenSan crew would sleep on the floor, one next to the other.

Correa entrusted Pacquiao’s day-to-day business affairs to Rod Nazario, a promoter with decades of experience, and Lito Mondejar, one of the co-founders of the gym. Nazario and Mondejar had a popular boxing show called Blow by Blow, which ran on the national public television station. Pacquiao soon became one of its star attractions. As an amateur, he’d been trained by Dizon Cordero, but Leonardo Pablo took over when he turned professional. Pablo, an older man who was blind in one eye, had been a fighter himself. With Pablo in his corner, Pacquiao won decisions in four of his first five bouts before he began sitting down on his punches to create knockouts.

(Photo by Gerhard Joren/LightRocket via Getty Images)

“In those early days, he was very reckless. He didn’t have much of a defense,” said Joaquin “Quinito” Henson, who commentated on many of those early fights with Ronnie Nathanielsz for Blow by Blow. “He had a lot of foot movement but no rhythm to his movement.”

“His style before was unlike when he went to Freddie Roach,” said former two-weight titleholder Gerry Penalosa. “He was like a street fighter. He had the heart. He wanted to kill you.”

As much glory as Pacquiao was gaining in these early fights, there was also great sorrow to counterbalance it. Two of the other fighters whom he’d traveled to Manila with would die shortly after arriving. Eddie Cadalzo, one of the fighters who slept on the floor alongside Pacquiao, died in his sleep. Another fighter, Eugene Barutag, died from injuries suffered in a fight on December 9, 1995. Pacquiao was in the next fight on the card, the main event, and cradled his close friend’s head in his gloves before he was taken to the hospital. With barely a moment to process what had happened, Pacquiao had to set aside his grief and go 10 rounds with Rolando Toyogon, winning a decision.

Nearly a year after turning pro, Pacquiao no longer had to put weights in his pockets before stepping on the scales. He was filling out his frame, as evidenced by his weigh-in mishap in a fight against a tough spoiler named Rustico Torrecampo in February 1996. Pacquiao came in a pound over the limit and had to wear eight-ounce gloves while Torrecampo wore six ounces. For the first two rounds, Pacquiao looked as sharp as he ever had, darting in and out, setting up his left hand with his jab and repeatedly stunning the underdog. Everything was going well until it wasn’t. Torrecampo caught Pacquiao flush on the jaw with a left in the third round, just as Pacquiao went to throw his own. When Pacquiao finally got back to his feet minutes after losing by knockout, he started bouncing on his toes and pumping his gloves like the fight was about to start.

The Torrecampo fight was the first time Rick Staheli had seen Pacquiao. An American military vet who taught himself to train by ordering VHS tapes from the U.S., he says he’d never seen a crowd as raucous as that night in Mandaluyong City. Despite the result, Pacquiao made an impression on him. Staheli began helping Manny in the gym and then took over as his head trainer in 1997, splitting the 10 percent cut with Pablo, who remained as assistant. Among the first things Staheli worked on was getting Pacquiao’s diet in order. As perhaps the largest flyweight in the world, Pacquiao’s greatest nemesis would be the scales. So Staheli substituted brown rice for white rice and multigrain bread for the sugar-filled pandesal bread.

“I’ll never forget Manny, he’s like, ‘Coach, why does it have peanuts in the bread?’ And I said they were actually little bits of barley in the wheat bread,” said Staheli.

Pacquiao’s stock got a major boost in June 1997 when he knocked out the dangerous Chockchai Chockvivat in five rounds to win the coveted OPBF flyweight title. Next, he traveled to Cebu City to face Melvin Magramo, a rugged if unrefined slugger who almost never stopped throwing wide punches.

So enthralled was he by the historic Cebu Coliseum, a place where legends like Flash Elorde and Bernabe Villacampo had fought, that Pacquiao left the dressing room and went out to admire the crowd.

“We chased him to the ring, and I go, ‘C’mon Manny, you’re not warmed up,’” said Staheli. “And he’s just looking around. He loved that spotlight.”

Shortly after the bell rang, Magramo caught Pacquiao cold, dazing the 18-year-old, who continued throwing punches on autopilot. Staheli could sense something was not right with his fighter. When the ring card girl passed by before the sixth, the trainer decided to test Pacquiao’s mental faculties: “I asked, ‘What round are we in?’ He said ‘Cebu.’ And I said, ‘Close enough.’” Staheli did his best to buy Pacquiao time to recover, taking his time fixing the glove tape in the eighth, much to the displeasure of bettors at ringside. Pacquiao won a decision, and Staheli found the quickest exit.

Body sore and racked with pain, the young Pacquiao trained in squalor with primitive, makeshift gym equipment. (Photo by Gerhard Joren/LightRocket via Getty Images)

As Pacquiao’s standing in the ratings went up, so did his paydays. Staheli says Pacquiao’s purses rose from about $1,000 for the Chockvivat fight to $3,000 for the Magramo fight, and then $7,000 for a first-round body shot knockout win over Narong Datchthuyawat on the Luisito Espinosa vs. Carlos Rios WBC featherweight title fight in December 1997.

Pacquiao’s rise caught the eye of Penalosa, who was passing through Manila on his way north to the mountainous city of Baguio for training camp. Penalosa, then the WBC junior bantamweight titleholder, was looking for a southpaw to spar with to prepare for his fight against Young Joo Cho in November 1997.

When the bell rang at LM Gym, the gap in experience showed.

“[Penalosa] just drummed the hell out of [Pacquiao],” said Staheli. “He actually knocked him down with a body shot. It was supposed to be four rounds, and he knocked him down in the second.” Staheli turned to Dodie Boy Penalosa, who was training his younger brother, and told him he was cutting the session by a round. Pacquiao came out for the third, swinging wild to impose himself, but Penalosa, the consummate technician, used that opportunity to take target practice.

Despite the outcome, Gerry Penalosa saw potential in the teenager.

“I knew it from the beginning that this guy would become big; he would become something,” said Penalosa.

Penalosa ended up paying Pacquiao 10,000 pesos for a month to work as his chief sparring partner. More than the money, it was an opportunity to learn from the fighter who Roach would later describe as the Philippines’ most skilled ever.

Pacquiao had his first ever fight abroad in May 1998, knocking out Shin Terao in one round in Japan. His second time getting his passport stamped that year would be a much steeper proposition.

“I knew it from the beginning that this guy would become big; he would become something.”

– Gerry Penalosa

It was two in the afternoon, a hot day at a public market just outside of Bangkok, Thailand, when Pacquiao got his first shot at a world title. Chatchai Sasakul, who held the WBC flyweight belt, was a popular star in his country, having been a 1988 Olympian. He won the title in Japan a year earlier, handing Yuri Arbachakov his only defeat, and had a boxer-counterpuncher style that seemed the perfect foil for the wild youngster. A hometown decision was the least of Staheli’s concerns.

“I knew he had to win by knockout,” said Staheli. “Forget bad decisions; this guy’s a good boxer. He’s a much better boxer than Manny.”

For the first seven rounds, that’s exactly how it played out, with the much larger Pacquiao stalking Sasakul, who calmly turned and landed counters upstairs and down. The pressure and body-punching from Pacquiao slowly began to wear down Sasakul, whose hands began to drop from fatigue. “He had strong determination,” remembers Sasakul. “He wanted to get the world championship from me very much.” That’s exactly what Pacquiao did in the eighth, landing a looping left to the jaw that put Sasakul on his stomach. Sasakul struggled to get back to his feet before falling face-first and tumbling to his back.

“Nobody cheered for me,” laughed Pacquiao. “They think that I’m an opponent for a tuneup fight for the champion of Thailand. But I knocked him out.”

Pacquiao’s popularity at home skyrocketed after winning the title. Shortly after arriving back home in Manila, a representative from the apparel brand No Fear locked in a deal that would define the fighter’s look for years. The billboards along major roadways like EDSA would soon bear his face, and A-listers in the country lined up to be photographed alongside him.

“When we staged his fights in Cotabato, people from all over Mindanao traveled long hours just to see him fight. Some arrived the night before and they waited for the gates to open as early as 6 a.m.,” said Manny Pinol, who had just been elected vice-governor of North Cotabato when he promoted a non-title card headlined by Pacquiao against Todd Makelim in February 1999. “I would say he is the most popular Filipino boxer ever, and his Cinderella story of rags to riches adds to the drama.”

Pacquiao dispatched Makelim in three rounds; it’d be his last fight with Staheli in his corner, as Pablo once again assumed the head-trainer role. Pacquiao headlined next at Araneta Coliseum, the site of “The Thrilla in Manila.” His opponent for the mandatory defense was Gabriel Mira, the first of many Mexican boxers he’d face. Though just 19-7-1 (15 KOs) entering the fight, Mira showed that he had some real power, hurting Pacquiao to the body with a left hook in the second round. After catching his breath, Pacquiao went to work and landed two lefts at the end of the session that put Mira on the canvas. “I felt good until he hit me in the last seconds of the round,” said Mira. “I did not recover 100 percent. I was fighting by instinct.” Pacquiao would score another knockdown in the third and three more in the fourth to win the fight by TKO.

One of the conditions for getting the fight against Sasakul was that the Thai promoter, Virat Vachirarattanawong, would get an option on a future Pacquiao fight. He cashed that in by bringing Pacquiao back to Thailand in September 1999 to face Medgoen Singsurat. By then, Pacquiao’s body had matured and making 112 pounds was becoming a more difficult feat. The day of the weigh-in, Pacquiao was still three pounds over, and the team became desperate. “They were rubbing calamansi (a sour citrus fruit) on his tongue to make him salivate, as if that would make a difference,” said Henson. Other ideas included cutting his hair and turning the bathroom into a makeshift sauna, but there wasn’t another drop of perspiration to be collected. Pacquiao missed the limit by a pound and was stripped of his belt. So drained was he that a shot that barely glanced off his midsection put him down for the count.

When Pacquiao returned to the ring three months later, he did so as a junior featherweight, passing two divisions to hit the restart button. Gone was Pablo, and Emil Romano, a former pro himself, was now in charge. “I told him before that you’ll knock out all of your opponents in the 122-pound division,” Romano said. “All of his fights with me, he won by knockout.” After four weeks to adjust to his new division and trainer, Pacquiao became the top 122-pounder in the Philippines by demolishing Reynante Jamili in two rounds.

It was smooth sailing until October 2000, when Pacquiao was matched with Nedal Hussein, an undefeated Australian with an iron chin and a serious punch. In the fourth round, Pacquiao found himself down by, of all punches, a jab. He smiled, half-embarrassed and half-dazed, and rose up after a long count by Carlos Padilla. “If you look at it, it was 17.1 seconds,” said Hussein. “I always trained against a southpaw (and knew) that the easiest punch to land was a jab. I didn’t have to load up that much for him to walk into it.”

Pacquiao was ahead on all three cards by the time the fight was stopped in the 10th because of a cut over Hussein’s left eye, which Hussein insists wasn’t bad enough to warrant a TKO.

Romano’s time in Pacquiao’s corner would be brief, lasting a little more than a year. When an opportunity arose for Pacquiao to travel to the states in search of the big fights, Romano stayed behind to look after the fighters in his stable who he’d been with longer. If Pacquiao had not walked into the Wild Card in Hollywood and so impressed Roach on the mitts that he took him on as a fighter, we may not have seen the greatest trainer-fighter tandem since Muhammad Ali and Angelo Dundee. Had he not been in the States, on weight and ready to step in for an injured Enrique Sanchez against IBF junior featherweight titleholder Lehlohonolo Ledwaba on two weeks’ notice, who knows how long it would have taken for him to break out.

But those events did take place, and it was the overlooked battles and setbacks that prepared him to make the most of the opportunities that lay ahead.

“I think that’s his destiny,” said Penalosa. “That’s why he became Manny Pacquiao. He’s once in a lifetime.”

SUBSCRIBE NOW (CLICK HERE - JUST $1.99 PER MONTH) TO READ THE LATEST ISSUE