A fan remembers Donald Curry-Lloyd Honeyghan 35 years later

“Physically, he wasn’t there and I just walked through him. Everything went the way I wanted. As far as the difference in our physical strength, it was like night and day. Most guys that I fight aren’t as strong as me…he wasn’t at all.”

That was how Donald Curry recalled his scintillating December 1985 second-round knockout over Milton McCrory in the June 1986 issue of KO, a knockout that allowed him to join Marvelous Marvin Hagler as the sport’s only undisputed champions. Given how awesome “The Lone Star Cobra” looked that night, no one would have ever suspected that the same words could have been spoken about him a little less than 10 months later.

On this day 35 years ago inside the small Circus Maximus Showroom at Caesars Hotel and Casino in Atlantic City, the boxing world – and Donald Curry’s world – was turned upside down by Lloyd Honeyghan, a British-based Jamaican who backed up his bold words with the performance of his athletic life. His sixth-round corner-retirement TKO over Curry not only was the upset of the year but arguably the upset of the 1980s given Curry’s standing entering the fight and the heights many thought he could have reached had he chosen a different path. Instead, the outcome of Honeyghan-Curry heralded the arrival of a new star, a star whose confidence and charisma complemented his violent in-ring style. He was undefeated, unpredictable, unvarnished and uncompromising.

At the time of this match, I was a 21-year-old who was just starting his sophomore year at Fairmont State College (now Fairmont State University), located just 26 miles southwest of West Virginia University in Morgantown. Although I was still in the process of majoring in English and minoring in journalism and technical writing, my boxing education was well into its 13th year, and I, like everyone else, was enthralled by Curry’s exceedingly bright future following the McCrory knockout. The boxing magazines – and Curry himself — laid out the hoped-for blueprint thusly: Curry would challenge for (and would be heavily favored to win) a championship at 154 (most likely against WBA titlist Mike McCallum) in June 1986, then jump directly into a fight with Hagler – the undisputed middleweight champion and the reigning pound-for-pound king — at the start of 1987. Given Hagler’s age (he’d turn 33 in May 1987) and the wear and tear he showed in his KO victory over John Mugabi in March 1986, many fans and pundits foresaw a triumph for Curry, who marked his 26th birthday 20 days before meeting Honeyghan.

Those visions were stirred by how polished and powerful Curry looked in the final moments of the McCrory fight; a perfectly-timed hook to the jaw scored the first knockdown, then, after McCrory arose, Curry pulverized “The Ice Man” with his final punch, a right to the jaw. That savage conclusion transformed Curry’s image from respected technician to Hagler’s heir apparent and a future all-time great.

Photo by The Ring Magazine/Getty Images

Curry’s team — which consisted of manager (and chief second) Dave Gorman, assistant trainer Paul Reyes (who had been with Curry even before the fighter became a teen-ager) and promoter Akbar Muhammad — initially intended to follow the accelerated schedule detailed two paragraphs earlier. It appeared to be the perfect match, for at the time of Curry-Honeghan, Hagler and Curry were The Ring’s reigning Co-Fighters of the Year. But Team Curry opted to remain at 147, partially due to advice Curry sought from Sugar Ray Leonard and Leonard’s attorney Mike Trainer – advice for which Curry would file a lawsuit shortly after Leonard defeated Hagler — and partially due to Curry’s desire to keep his undisputed championship for a little while longer.

“There is nothing available for me to do at junior middleweight right now,” Curry told KO senior writer Jeff Ryan in the June 1986 issue, which was conducted that February. “I wanted to go right for one of the titles but (WBC titleholder Thomas) Hearns is fighting James Shuler (on the March 10 Hagler-Mugabi undercard) and (WBA titleholder Mike) McCallum is defending his title (though not until August against Julian Jackson). Carlos Santos, the IBF champ, nobody really thinks too much of him. It wouldn’t be a waste of time, but everybody would expect me to win and win big. Santos wouldn’t be a real interesting fight.

“I decided to bring the unified title back to (my hometown of) Fort Worth for a fight because I worked so hard to get it and I didn’t want to give it up right away before defending it,” Curry continued. “Not having much trouble making 147 for Milton also made me say, ‘why not stay here?’”

But Curry did have problems making 147 against Panamanian southpaw Eduardo Rodriguez, the WBA’s No. 1 challenger, before scaling 146 ¾ to Rodriguez’s 146 ½. The fight took place on March 9 – the day before Hagler-Mugabi – and following a surprisingly competitive first round for which two judges submitted 10-10 scores, a pair of Curry left hooks scored the 10-count knockout at the 2:29 mark of round two, lifting his record to 25-0 (19) and his knockout streak to a career-high seven.

Photo by The Ring Magazine/ Getty Images

Meanwhile, Honeyghan – rated sixth by the WBC and third by the WBA thanks to his status as the British, Commonwealth and European champion – secured his crack at Curry by knocking out Horace Shufford, the WBA’s No. 1 challenger for the past 18 months, in the eighth round of a final eliminator staged at Wembley Arena on May 20, 1986. A pile-driving right to the jaw floored the 33-year-old American in Round 4, and Honeyghan ended the fight in Round 8 with a left hook that left the semi-conscious Shufford tangled in the ropes. With the victory, Honeyghan raised his record to 27-0 (17) and his ranking to No. 1 in the WBC and No. 3 in the WBA behind South Africa’s Harold Volbrecht and Canada’s Davey Hilton.

Honeyghan’s whirling dervish attack was crafted under new trainer Bobby Neill — himself a British featherweight champion from April 1959 to September 1960 — and Honeyghan’s political clout increased exponentially thanks to hiring a new manager in Mickey Duff, who, with Jarvis Astaire, Terry Lawless and Mike Barrett, formed a partnership that dominated British boxing for more than two decades.

Neill’s appointment came at the behest of Duff, and Honeyghan jumped at the chance to work with him.

“I heard a lot about him when I was an amateur, and I knew he was the best,” Honeyghan said in the August 1986 issue of The Ring. “From the first day we met, we got on straight away. He’s the best thing to happen to me in a long time.”

That confidence was justified by the Shufford victory, and while domestic fans severely doubted his chances of beating the mighty Curry, Honeyghan and his team brimmed with confidence.

“Everybody seems scared of Curry, but I’m not,” Honeyghan asserted in the August 1986 Ring. “If he fights me like he fought Colin Jones, I’ll beat him. And if I tag him the way I tagged Shufford, he’ll go down. Nobody is unbeatable.”

“We are going to push for the fight right away,” Duff declared. “We don’t want any messing about. I’m taking a tape of this fight to the three American networks. Honeyghan showed more power, more style, more of everything than I imagined he had.”

If Duff indeed approached the executives at ABC, CBS and NBC, the gambit didn’t work; Showtime would air the fight live while ESPN secured the delayed-broadcast rights.

Honeyghan trained for the Curry fight in New York’s Catskill Mountains along with fellow Duff client Cornelius Boza-Edwards, who was set to fight WBC lightweight champion Hector Camacho in Miami Beach the night before Curry-Honeyghan. But while the intensely focused Honeyghan toiled in isolation, Curry was beset with a series of distractions, most of which were of his own making.

Curry — who was making the eighth defense of his WBA title, the sixth of his IBF strap and the first of the WBC belt he won from McCrory — had struggled with the 147-pound limit even before he became champion thanks to his love of fast food.

“I had very bad eating habits when I was out of training,” Curry admitted in the KO magazine interview conducted before the Rodriguez defense. “I would get heavy from too many burgers and cokes. I love burgers. Well, I did. The only time I really, really had trouble and wanted to move out of the division for good is when I fought (Nino) LaRocca (in September 1984). I guess I got so far up that it was almost impossible to come down. It’s been hard making the weight, even for the Colin Jones fight (in January 1985), but I made it. And for (Pablo) Baez (in June 1985), I had to lose a half-a-pound or a pound the day before the fight.”

Curry began training for the Rodriguez bout at a relatively modest 156 but for the Honeyghan match Curry blew up to 168 and was still 11 pounds over the limit 10 days before the opening bell. The uncertainty weighed so heavily on Curry’s mind that he thought about canceling the match.

“Donald came in (two weeks before the bout) and said to me, ‘look, I don’t think I can make this weight. Maybe we should just drop the fight and I can get a junior middleweight fight.’” Muhammad said shortly after the match. “I said, ‘Donald, I think you have a professional obligation to go ahead and make the weight and fight.’ Even then he realized he was having problems making the weight.”

In addition to the stresses of weight-making, the recent death of Curry’s grandfather as well as a dispute with his management team deepened Curry’s duress. Two weeks before the match Curry announced that once their current agreement expired three days after the Honeyghan bout, he would keep 80 percent of the purses while slashing Gorman’s 30 percent managerial cut to that of a consultant earning five percent, Paul Reyes’ assistant trainer’s share to five percent and Muhammad’s promoter’s slice to 10 percent. Moreover, Gorman, who had managed Curry his entire pro career, wasn’t welcomed into camp until three days before the match, and instead of training in Arizona as was the case for previous fights, Muhammad arranged for Curry to train in New Orleans.

“When a guy is trying to make weight, he should be working in a dry climate, not a humid one,” Gorman told KO’s Jeff Ryan. “Humidity saps too much strength. And besides all that, fighters are creatures of habit. Change isn’t always good.”

In the meantime, Honeyghan was rounding himself into peak physical condition while also working up an emotional froth that enhanced his already unbreakable self-assurance. According to the Associated Press, Honeyghan looked at tapes of Curry’s victories over LaRocca and Starling (second fight) and came away knowing he would win.

“I watched the tapes twice and gave them to my trainer,” Honeyghan said. “I told him, ‘I’ve seen enough.’ I’m a quick learner.”

Despite his undefeated record, Honeyghan was seen by most observers as just another British fighter who would wilt the moment he stood across the ring in America against a top-shelf American champion. He was such a profound underdog that some gambling establishments refused to put the fight on their boards. Those that did had Curry a 6-to-1 favorite, but the odds probably would have narrowed greatly had bettors at large gotten a glimpse of Curry and Honeyghan at the weigh-in. Although both weighed 146 ½, Honeyghan’s weight distribution and physical presence was far superior to that of Curry, whose bony face and meatless ribs stood in stark contrast to the toned assassin that snuffed out McCrory.

“He looked emaciated,” said Top Rank’s Bob Arum, the promoter of the bout. “He had no zip, no nothing.”

The intervening hours of rehydration did little to improve Curry’s physical state, and those final hours before fight time only heightened Honeyghan’s hunger to shock the world.

But those closest to the challenger were convinced that even the best version of Curry would have been troubled by Honeyghan’s relentless pressure, two-fisted power, supreme self-confidence and defiant ferocity.

“He’s certainly one of the most dedicated boxers I’ve been involved with,” Duff said shortly before the Curry fight. “I don’t know of anybody who trains harder for a fight harder than he does. For six weeks before a fight he turns himself into a hermit; he goes to the gym, goes on the road to run, he eats, and the rest of the time he spends in the room isolated with a television set, and he’ll watch TV and go to sleep. Lloyd Honeyghan has got the toughest fight he’s ever had in his whole career. And equally, Donald Curry has the toughest fight he’s had in his whole career. This is, in my mind, undoubtedly, the toughest opponent that Donald Curry has fought to date.”

Both fighters appeared focused and relaxed upon entering the arena, and the opening moments of the contest were spent identifying range and ascertaining timing. It was immediately apparent that Honeyghan was at least Curry’s equal in terms of hand speed and superior as far as foot speed as he nipped in and out of range while also rolling his upper body. He was not in awe of the occasion, the stakes, and especially the opponent. Although Curry landed several sharp jabs, it was Honeyghan who began and ended most of the skirmishes and he won the round by landing several right hands, especially in the session’s final 30 seconds.

“When I took the first jab, I knew something was wrong,” Curry said in the post-fight report printed in the December 1986 Ring. “I just didn’t have anything. It was gone.”

The first indicator that this could be a special night for the challenger came 23 seconds into Round 2 when a lead overhand right to the jaw buckled Curry’s legs. The champion steadied himself in the nick of time but the opportunistic Honeyghan immediately pounced, winging wild punches and using his upper body strength to shake himself free from Curry’s clinches.

“The Cobra may have a mongoose with him,” exclaimed Bill Mazer, the blow-by-blow man for Showtime.

“He seemed to be confident before the fight, he’s not showing Curry any respect at all,” added analyst Gil Clancy. “He’s going out to win the title; that’s what he’s supposed to be doing, and he is.”

“Curry may be thinking about Hagler, but he’d better start thinking about this guy first,” concluded Mazer.

Curry landed several hooks and crosses, but Honeyghan absorbed them with aplomb and he answered with short, crisp counters at close range. Not only did he have fast hands, he also showed himself to be a handful on the inside as he dug to the short ribs, bulled Curry around in the clinches and landed several compact uppercuts. One of those uppercuts cut Curry’s lip, and once the champion returned to long range, Honeyghan drilled Curry with several combinations that swiveled the Texan’s head. Honeyghan was fighting with more energy, was punching with more authority and was exerting dominion over the proceedings while Curry appeared confused, reactive and out of sorts.

Honeyghan continued to pressure Curry at the start of the third behind piercing jabs and looping rights that just missed the mark. Meanwhile, Curry fell into the trap of looking for the one big punch that could turn the fight his way, and, spotting this, his corner yelled for their charge to “pick it up.” Curry did just that with a little more than a minute left in the round when he nailed Honeyghan with a left to the belt line, a right uppercut that just missed and an overhand right to the jaw that earned the challenger’s notice. Honeyghan managed to ride out the mini-storm, but that sequence was enough for Curry to win his first round on all three scorecards.

In the wake of Curry’s success, Duff sought to get his man back on track.

“You knew sooner or later you were going to take a shot off him; you’re well prepared for that, aren’t you?” Duff said matter-of-factly. “Right. So that’s a lot of bother; it’s happened and it’s over, right? Now let’s get back to basics and being the governor. Coming out of a clinch, you move your head. You don’t stand still, that’s how you got caught. You don’t lean back; you lean back and around in again, around in again. You understand? That’s the main thing. Another two rounds, you’re going to be fine. Put the pressure on him.”

Photo by The Ring Magazine/ Getty Images

Honeyghan responded to Duff’s advice by bolting from his corner and firing a big right at Curry’s chin, sending the message that he indeed was the governor of this ring – and, if the trend continued, to be the governor of the welterweight division. But Curry, depleted as he must have felt, still had professional pride, and he finally began executing the skills that were good enough to have achieved a mind-blowing 400-4 amateur record, a spot on the 1980 U.S. Olympic team that was barred from competing in Moscow thanks to the boycott imposed by President Jimmy Carter, and 25 straight wins as a pro. A heavy left to the body briefly halted Honeyghan’s progress and a counter right to the chin scored moments later. Comparatively speaking, Round 4 was Curry’s best, but a case could be made that Honeyghan’s first-half effort was enough to counteract Curry’s late rally. Judges Charlie Spina and Larry O’Connell awarded Curry the fourth while Jose Juan Guerra saw it even, but Clancy gave Honeyghan the session, stating – with some justification — that Honeyghan was the busier fighter who landed more punches.

Any momentum Curry might have gained from rounds three and four was snuffed out early in the fifth when Honeyghan connected with a snappy one-two to the face that rubberized the champion’s legs and a scything right uppercut to the tip of the chin that forced Curry to break his hoped-for clinch. For the first time, visions of a gigantic upset were lighting up inside many heads, including those of Mazer and Clancy.

“I don’t believe this,” Mazer said, a trace of despair in his voice.

“This is boxing,” replied Clancy. “We’ve seen big upsets, but, if in fact, it takes place tonight, this will rate as one of the biggest in history. Here, we’re talking about a kid a lot of people said could be one of the greatest, and in this particular moment he’s in trouble.”

As the round continued, Honeyghan connected with crosses almost at will, and Curry had no answers at his disposal. All he could do was back away and limit the damage, and when Curry attempted to clinch, Honeyghan pushed him off with his shoulder. Curry glanced toward his corner, but as he did so, Honeyghan cracked him with yet another right. For Curry, it was a nightmare coming to life but for Honeyghan this was a dream in the process of becoming reality.

The fifth was the most dominant round by either man, and given how fresh Honeyghan looked, one had to wonder if Curry could complete the seven scheduled rounds that remained.

As the sixth commenced, Curry stared intently at Honeyghan, hoping that the challenger would give him the one opening he so desperately needed. But Honeyghan, fueled by ambition and the prospect of life-changing success, gave him nothing but speed, power and talent. Eighty-one seconds into the round, Honeyghan accidentally gave Curry something else: The upper part of his head. The clash opened a three-inch gash under Curry’s left eyebrow that would require 20 stitches, and as the crimson trickled from the wound, so did Curry’s will to continue competing. For him, it was the final straw.

“Tonight, in the first round, I knew I wasn’t myself,” Curry said afterward. “In the third and fourth rounds, I tried to knock him out because I knew my legs would never make it. When he cut me and the blood flowed into my eyes, I knew the fight was over.”

He managed to survive the rest of the round, but as he walked toward the corner, he shook his head in frustration and resignation. Once he plopped on the stool and cut man Joe Barrientes worked on the wound, he informed his team that he would fight no more.

Photo by The Ring Magazine/ Getty Images

With that, it became official: Lloyd Honeyghan was the new undisputed welterweight champion of the world. It was history repeating itself, for the last time a fighter hailing from England won the 147-pound championship in December 1975, John H. Stracey traveled to Mexico, the adopted homeland of champion Jose Napoles. and won the crown by a sixth round TKO. It was the biggest upset scored by a British fighter since Randy Turpin, as a 3 ½-to-1 underdog, dethroned world middleweight champion Sugar Ray Robinson in July 1951, and it rated with some of the greatest surprises in boxing annals: 10-to-1 underdog James J. Braddock over then-heavyweight champion Max Baer in June 1935, Max Schmeling beating Joe Louis in their June 1936 showdown as well as the 6-to-1 odds against him, 10-to-1 underdog Lauro Salas outpointing lightweight king Jimmy Carter in 1952, 5-to-1 underdog Ingemar Johansson crushing heavyweight king Floyd Patterson in June 1959, Cassius Clay stopping 7-to-1 favorite and heavyweight champion Sonny Liston in February 1964, Muhammad Ali knocking out 3-to-1 favorite George Foreman to regain the heavyweight championship and 7-to-1 underdog Leon Spinks turning the tables on Ali in February 1978 among them.

“I said I was better than Donald Curry and I deliberately came to America to prove it,” Honeyghan said at the post-fight press conference. “I wanted to show the American people I’m the true champ. When I was 12, I saw Muhammad Ali on television and I said to my dad ‘I want to be just like that man; I want to be champion of the world.’ All the praises people have been giving to Curry, they can now give to me.”

Honeyghan’s said in the September 1987 issue of KO that his brief film study revealed an easily exploited weakness.

“He just comes out with his hands up, and there’s a big gap in his two hands. And he’s square. He’s completely square,” he said. “I’ve got very good eyesight. And I’m very sharp. And seeing him like that, I just knew I’d beat him if he fought me.”

Curry skipped the post-fight press conference in order to have his cut treated, but in his hotel suite afterward he said the following:

“I have to come back and work harder. Everyone gets beat. I’ll take some time off to get myself together and then I’ll go back at it. I still think I’m the best fighter in the world and I’m going to prove it. But there will only be a rematch if he comes up to junior middle. There’s no way I’m going to make welter; 147 is over.”

For Curry, there would be no rematch with Honeyghan, but he did fight McCallum for his WBA junior middleweight championship in July 1987 at Caesars Palace Sports Pavilion in Las Vegas. Curry, the 2-to-1 favorite, nearly dropped McCallum with a right in Round 2, but “The Body Snatcher” baited Curry with a slow right to the body that caused the challenger to drop his guard, then scored the 10-count KO in Round 5 with a flush hook to the jaw. The loss – his second to a native of Jamaica — confirmed that Curry never again would walk into a ring as a pound-for-pound candidate, and while it’s true that Curry eventually won a 154-pound belt against Gianfranco Rosi in July 1988, his loss to Rene Jacquot seven months later was deemed The Ring’s 1989 Upset of the Year, which caused Curry to join Muhammad Ali, Roberto Duran, Marvelous Marvin Hagler, Mike Tyson and Wladimir Klitschko as fighters who were on the wrong end of multiple Upsets of the Year as judged by The Ring.

The result of Honeyghan-Curry was a shock to this early twentysomething, and while I didn’t see the fight live, I recorded the replay on ESPN’s “Top Rank Boxing” series onto Tape 12 of my VHS collection (I still have the recording, and it looks as good as the night I recorded it). I was so enthralled by Honeyghan’s performance that I brought the tape with me to Thanksgiving dinner at the house of my aunt Estella (my mother’s sister) and my uncle Bill. Bill and his son, my cousin Greg, were casual boxing fans and once I explained why I was showing the fight they seemed to enjoy it. What was unusual about the ESPN replay was that they not only showed the entire fight, but also aired the original commentary by Mazer and Clancy instead of having ESPN broadcasters Tom Kelly and Al Bernstein lay in their own call.

Curry lost the sheen of an undefeated record and the brilliance of possibility against Honeyghan, but his accomplishments garnered enough votes to be enshrined into the International Boxing Hall of Fame as part of its Class of 2019. His final record stands at 34-6 (25).

“The Ragamuffin” man notched three successful title defenses against Johnny Bumphus (KO 2), Maurice Blocker (W 12) and Gene Hatcher (KO 1) before suffering his own shocking loss against Jorge Vaca via eighth-round technical decision. Honeyghan regained the belt from Vaca inside of three rounds five months later, but, after stopping Yung Kil Chung in five, he became an ex-champion for good after Marlon Starling picked him apart on his way to a ninth-round TKO in February 1989. Honeyghan fought on until February 1995 and ended his career with a 43-5 (30) record. But when one speaks of Honeyghan’s career from now until the end of time, his sports-shaking triumph over Curry exactly 35 years ago will forever be part of his story.

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, West Virginia. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 20 writing awards, including two first-place awards, since 2006. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. as well as a panelist on “In This Corner: The Podcast” on FITE.TV. He is the author of “Tales from the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics” (available on Amazon) and the co-author of “Muhammad Ali: By the Numbers” (also available on Amazon). To contact Groves about a personalized autographed copy, use the email [email protected] or send him a message via Facebook or Twitter (@leegrovesboxing).

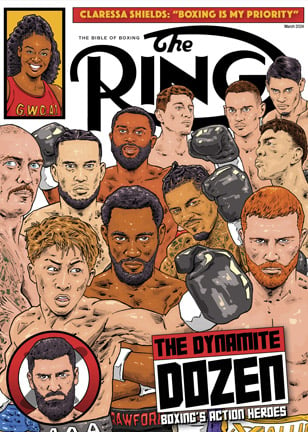

READ THE MARCH ISSUE OF THE RING FOR FREE VIA THE NEW APP NOW. SUBSCRIBE NOW TO ACCESS MORE THAN 10 YEARS OF BACK ISSUES.