Salvador Sanchez-Wilfredo Gomez: Battle of the Little Giants 40 years later

On August 21, 2021, Yordenis Ugas and Manny Pacquiao will step inside a Las Vegas ring – the T-Mobile Arena — to settle several issues: (1) Who is the better fighter between the two? (2) Who should be the rightful owner of the highest-tiered belt offered by the WBA, a belt that Pacquiao previously owned thanks to his July 2019 victory over Keith Thurman and that Ugas now owns thanks to the sanctioning body stripping the inactive Pacquiao and elevating the Cuban on January 31? (3) Who should be best positioned to challenge fellow titlists Terence Crawford and Errol Spence Jr., the former roadblocked by promotional barriers and unproductive exchanges with Team Spence and the latter sidelined by a detached retina suffered just days before the match. Spence’s exit also means that The Ring championship belt will remain vacant and that the true identity of the world’s best 147-pounder will not be determined for the foreseeable future.

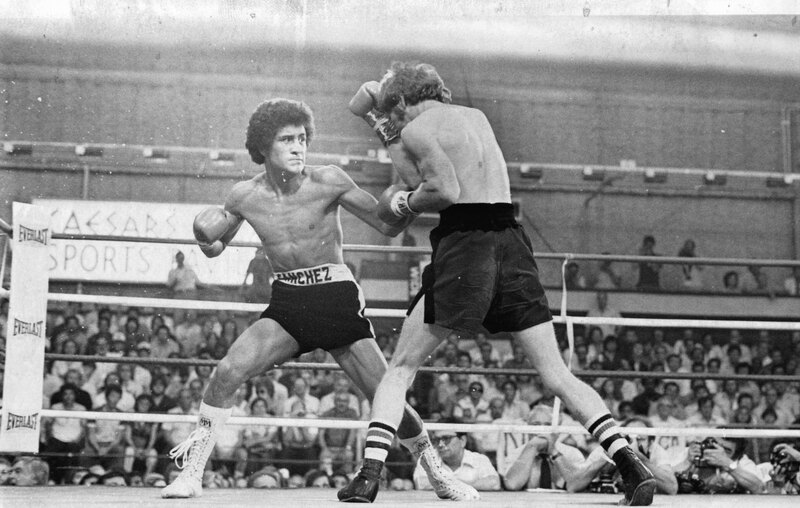

Exactly 40 years before Ugas-Pacquiao, Salvador Sanchez and Wilfredo Gomez stepped inside another Las Vegas ring – the Sports Pavilion inside Caesars Palace – to settle several issues: (1) Can the greatest 122-pound fighter who had yet lived step up four pounds and dethrone an impressive young champion? (2) Can the same Sanchez chin that unflinchingly absorbed 27 rounds’ worth of Danny “Little Red” Lopez’s bombs hold up against those of the “Bazooka,” who had stopped each of his last 32 opponents? (3) Which man would be best positioned to face WBA counterpart Eusebio Pedroza, who, to this point, had notched 12 successful defenses in a reign lasting more than three years?

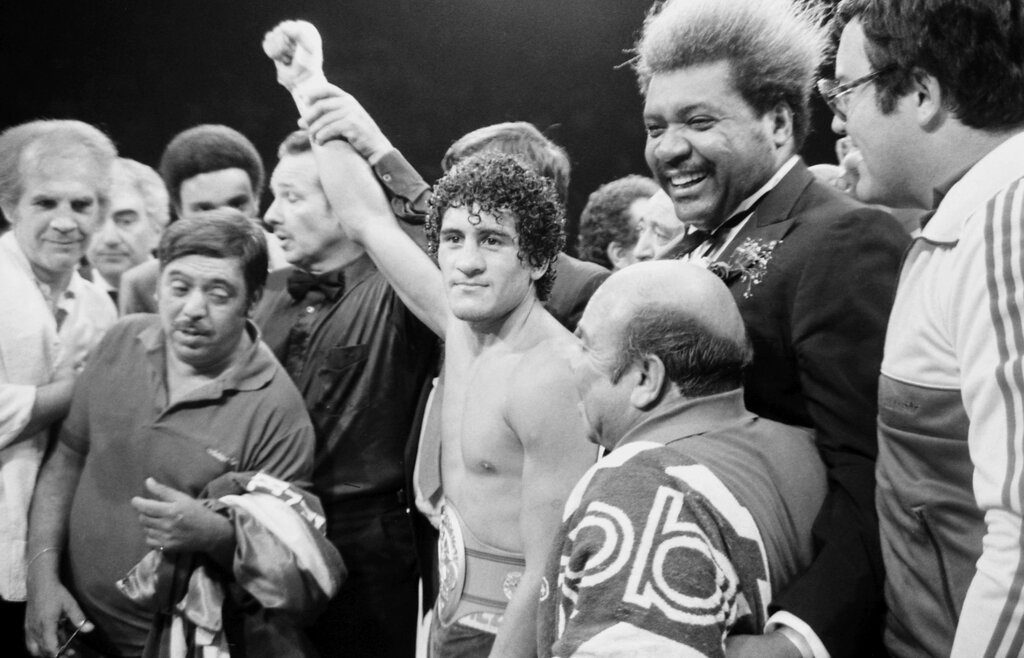

Because Sanchez and Gomez were featured regularly on American television – and because both men were promoted by the flamboyant Don King – their showdown was among the most eagerly anticipated lower-weight showdowns in years, so much so that it was called the “Battle of the Little Giants.”

Interestingly, it was Gomez, the naturally smaller man, who was the bigger attraction, the more proven commodity at championship level and the solid favorite to emerge victorious. The primary reason for this belief was that Gomez had already knocked off an undefeated Mexican icon in Carlos Zarate more than two years earlier as a slight underdog. On October 28, 1978 before a deafening hometown crowd in San Juan, the 21-0-1 (21) Gomez faced the 52-0 (51) Zarate on the eve of his 22nd birthday, and, to the world’s astonishment, the extraordinarily poised youngster out-speeded, out-boxed, out-foxed and ultimately knocked out the knockout artist 44 seconds into Round 5. Since then, Gomez added 11 wins and 11 knockouts – including seven in title defenses – to extend his all-time record of consecutive title-defense knockouts to 13, smashing Roberto Duran’s previous mark of 10. Gomez’s victory over Zarate – a red-banner chapter in the long-running rivalry between Mexico and Puerto Rico – vaulted Gomez to iconic status in his home nation and propelled him up the mythical pound-for-pound ratings. To many, the Sanchez fight represented just the next step in Gomez’s march toward fistic immortality.

A second reason to like Gomez’s chances was that his weight-making process was, at least in theory, made easier by fighting for the featherweight title. For years, Gomez had struggled mightily to squeeze his 5-foot-5 ½-inch frame down to 122, an effort which often required multiple trips to the scale. With four fewer pounds to sweat off, many believed Gomez would be stronger, more comfortable and better able to execute his multi-dimensional skills. Yes, Sanchez stood one inch taller and owned a three-and-a-half-inch longer wingspan, but Gomez proved against Zarate that he could handle rangy fighters just fine. For these reasons, Gomez was a 9-to-5 favorite to dethrone Sanchez.

Sanchez lifted the title from the brilliant Danny Lopez and also defeated him in a rematch. Photo by The Ring Magazine/ Getty Images

For several years, it was thought that Gomez’s inevitable featherweight title challenge would occur against Lopez, a dynamic power puncher who repeatedly overcame early knockdowns to knock out his challengers. When he faced Sanchez on February 2, 1980, one wag termed it “Little Red vs. Little Known” because the majority of the fights in Sanchez’s 33-1-1 (27) record to that point were staged in Mexico and far away from American television screens. But Lopez’s manager Bennie Georgino knew all about the talented Sanchez because “Chava” had fought on the untelevised undercards of Lopez’s title defenses against Mike Ayala and Jose Caba and saw that Sanchez’s skill set was all wrong for his man. Once Sanchez ascended to the No. 1 spot in the WBC ratings, Georgino did his best to keep Sanchez at bay for as long as possible.

“He was the big hurdle for us,” Georgino told this scribe in the September 1991 issue of The Ring. “Had Sanchez not come along, (Lopez) would probably still be champion. I didn’t like the fight because Sanchez moved side to side, threw his combinations, and got out. He knew better than to stay there and trade with Danny. I can’t say anything bad about (then-WBC president Jose) Sulaiman because he gave us the opportunity to stay with the title. But the time came when we had to fight Sanchez.”

And when Sanchez fought Lopez, all of Georgino’s fears came true as the 21-year-old sliced, diced, dissected and eventually disposed of Lopez by 13th round TKO.

“I had seen him fight at the (Los Angeles) Sports Arena and I said, ‘this guy isn’t bad.’” Lopez said in the same story. “(In the first fight) I was in shape and I never got tired. He just had me wired. He watched films of my fights over and over, and he had it down where he knew where to hit me. I just couldn’t land my blows. If I could’ve hit him on the chin, I could’ve knocked him out, but I never could hit him.”

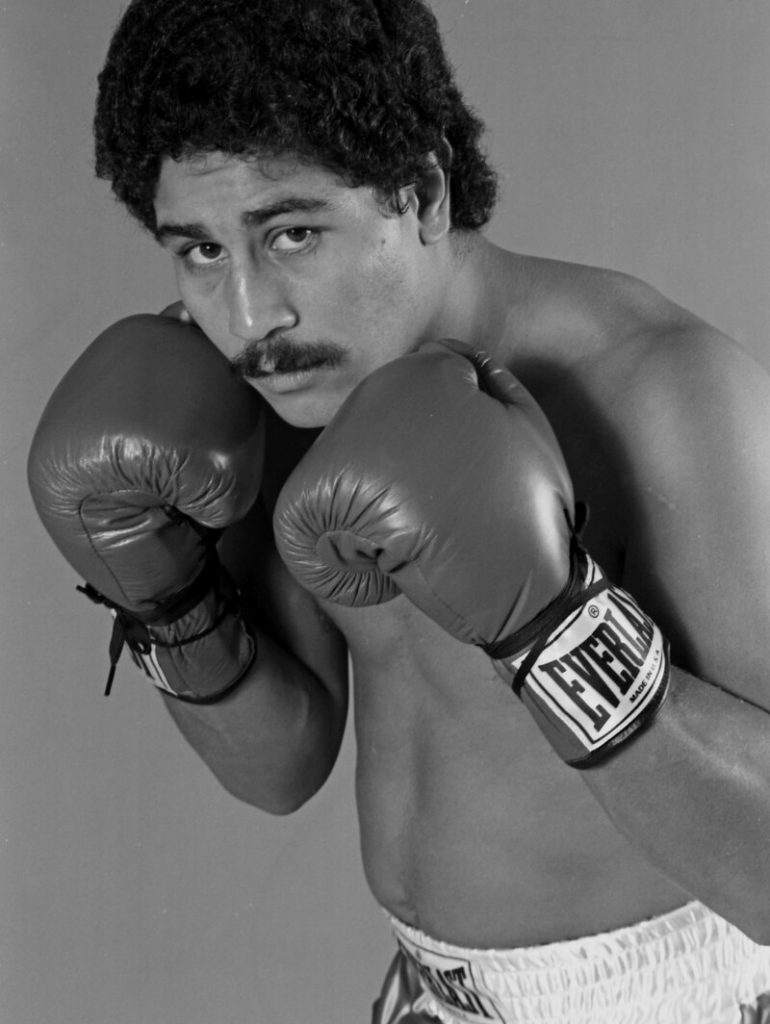

As serene as Sanchez appeared on the outside, his mind and his emotions were churning.

“As the fight progressed, I thought how nice it would be to drive beautiful cars and wear nice suits and expensive jewelry,” he told The Ring’s Rafael Mendoza in the August 1981 issue. “I felt great inner emotions during the fight. Never before did I ever feel so good and relaxed. I was hitting him with combinations like I never did before with any other opponent. This is the night I will never forget.”

Sanchez’s performance against Lopez was a revelation, and he quickly proved that the sublime talent he displayed was no fluke as he defeated quality challengers in quick succession. Just 70 days after dethroning Lopez he out-pointed Ruben Castillo, whose only previous loss in 45 fights was to then-WBC junior lightweight titleholder Alexis Arguello. Seventy days after that, he consolidated his title-winning 13th round TKO over Lopez with a 14th round TKO that forced “Little Red” into retirement for more than a decade. He finished a sterling 1980 with decision victories over Pat Ford and Juan Laporte, then began 1981 with a 10th round TKO in March over 43-1 Spaniard Roberto Castanon, whose only defeat was a second-round TKO to then-champion Lopez a little more than three years earlier.

Photo by The Ring Magazine/ Getty Images.

Both men warmed up for their date with destiny with non-title victories; Gomez crushed 26-13-5 (9) journeyman Raul Silva on June 20 in San Juan while Sanchez out-pointed previous Gomez KO victim Nicky Perez over 10 rounds on July 11. Gomez was at ringside for Sanchez-Perez and was not impressed by what he saw. When Gomez entered the ring to face off with Sanchez, it was clear he had several pounds to shed and not much time to shed them. Although the video suggested their exchange was playful, Perez believed Gomez was determined to communicate a more hostile message to Sanchez.

“He jumped into the ring as soon as the fight ended,” Perez told Gomez biographer Christian Giudice in “A Fire Burns Within.” “He tried to box Sanchez right there. He was chasing Salvador.” Gomez said his aggressiveness was no act. “It was not a set-up. It was very serious. When I went into the ring, I told him I wanted the opportunity to fight with him and I would take his head off.”

Gomez continued to taunt, berate and belittle Sanchez at every opportunity while Sanchez kept his emotions under control and allowed Gomez’s insults to serve as fuel for fight night.

“I was the champion. He was only the challenger – and a big-mouthed challenger at that,” Sanchez told Rivera. “I was sure of my victory before the fight began. I knew it from the first time I met Gomez and he started talking like Muhammad Ali. There is no way he or anybody else can intimidate me with a bragging act. That stuff is just an act to build up the gate or interest in a match. I know I am a better boxer than Gomez, a sharper puncher with better speed and reflexes. I am also 100-percent more professional. There is no way I could have lost to him. I respect Wilfredo as a fighter. But not as a person.”

The animus between Sanchez and Gomez extended to their fan bases, and national pride was at its core. The Puerto Rican fans dearly wanted their hero to score a second win over a top-flight Mexican while the Mexicans saw Sanchez as their vehicle to exact revenge on Gomez for his foul-filled victory over Zarate. The fight could only be seen live on closed-circuit, and it was such a hot ticket that, according to an item printed in the August 1981 issue of The Ring, counterfeiters sold exact replicas of tickets for the New York City showing at the Momentum and got away with it because the ticket takers could not tell the difference between the fakes and the genuine articles. The fights that must have broken out between two ticket-holders with the same seat number had to have been as fierce as the combat they hoped to see in the ring.

While Sanchez’s famously Spartan training camp proceeded without a hitch, the same could not be said of Gomez’s. According to Giudice’s book, Gomez received notice of the August 21 date while on a cruise ship during his honeymoon, and Gomez’s pleas to promoter Don King to postpone the fight went unheeded. Gomez rushed back to San Juan to begin six weeks of training but, like Gomez’s hero Roberto Duran had been before his rematch with Sugar Ray Leonard, his mind was focused as much on dropping pounds as it was on dropping sparring partners.

The race down to the 126-pound championship limit proved harrowing for Gomez. He was reportedly 11 pounds overweight by the start of fight week and was still four pounds over at midnight on fight day. At 4:30 a.m. – just four-and-a-half hours before the weigh-in — Gomez ran on a nearby golf course wearing a plastic suit and when he returned to his room, the scale there indicated he was still two or three ounces over. Unlike today’s protocol of day-before weigh-ins, the Sanchez-Gomez weigh-in was staged the morning of the fight, and time was running out on the Puerto Rican. Sanchez, whose distance-running prowess had earned him the nickname “Iron Lung,” was an impeccably conditioned 126 while Gomez, forced to move heaven and earth to wring out every possible ounce, somehow hit the limit with nothing to spare.

The nationalistic rivalry extended to the atmosphere inside the sold-out Sports Pavilion as a Puerto Rican salsa band brought in by Gomez dueled with a Mexican mariachi group. Gomez was the first to enter the ring, and, amazingly, his solid physique and relaxed, smiling demeanor revealed nothing of the hell he endured just hours earlier. Meanwhile the pumped-up Sanchez almost bounded into the ring and reveled in the adulation he received from his fans as well as the music from the band, which now was standing on the ring apron. Blow-by-blow man Bob Sheridan said the big-fight atmosphere gave him chills, and that feeling surely extended to everyone else watching the pre-fight pageantry.

Shortly after Sanchez settled in his corner, Gomez’s band upped the ante by entering the ring, playing a tune and dancing while looking directly at Sanchez. At first, Sanchez turned his back and shadow-boxed but then turned back toward the band with a smile and grooved with the music, which now was accompanied by Sanchez’s group. Although the crowd was heavily tilted toward Sanchez, Gomez’s band won the musical war with sheer volume. It was a light-hearted start to what promised to be a pulse-pounding battle.

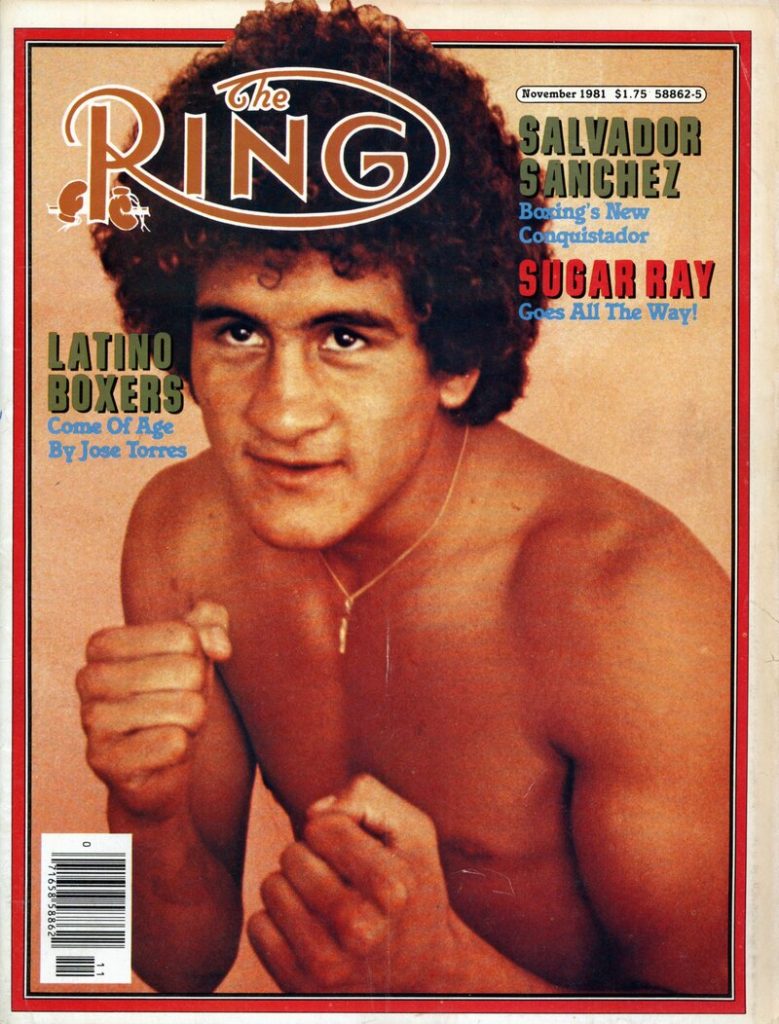

November 1981 issue.

The conventional wisdom was Gomez by knockout or Sanchez by decision, but it was Sanchez who produced the first shocking display of power. At the 1:22 mark of Round 1, Sanchez, with his back to the ropes, nailed Gomez with a scorching right to the chin, then followed with a right cross-left hook that put the challenger on his rear end. Gomez quickly regained his feet but Sanchez – who scored 17 knockouts in his first 18 fights – sensed the Puerto Rican already was ripe for the taking and went all out for the early ending. Sanchez’s merciless assault had Gomez reeling about the ring on rubbery legs. Several follow-up rights caused Gomez’s knees to buckle, but the challenger’s survival instincts not only kept him upright but commanded him to fight back. The blows that ended his last 32 fights inside the distance now were slow, soft and off-target while Sanchez’s were stiletto sharp and ceaseless. The worst 90 seconds of Gomez’s pro career to date ended with him still on his feet, but badly damaged because sometime during the round he suffered a broken right cheekbone.

“It’s a miracle that he got through that round,” Sheridan declared as Gomez trudged back to his corner.

“It’s a miracle he got through that round, and it’ll be a miracle for Gomez to come back this round,” replied analyst – and WBC heavyweight champion – Larry Holmes. “We gotta see how much that round took out of Gomez. Again, his corner is working very hard on him, but I don’t see any chance for Gomez.”

As Gomez’s seconds feverishly worked on a scratch under the right eye and a swelling on the cheek, Sanchez was the picture of serenity. Sanchez’s shoulders rested against the red corner post, both legs were fully extended, his breathing pattern was barely noticeable despite the torrent of blows he had just released and his face wore a blank expression, as if he were waiting his turn to be called upon at the DMV instead of engaging in the most important prize fight of his life.

The 60 seconds between rounds weren’t enough for Gomez to completely clear his head; his eyes were somewhat glassy and his mouth hung open, but once the action resumed, his pride and instincts pushed him to fight back as long and as hard as he could. He slipped under several Sanchez bombs, maneuvered him to the ropes, and commenced a heavy exchange that saw him land his share of blows. When Padilla’s break allowed them to return to ring center, it was obvious to Sanchez that Gomez had recovered sufficiently enough from his opening surge to throttle down and return to his long-range game.

While Sanchez’s powerful jabs continued to snap Gomez’s head, Gomez somehow seized the role of aggressor, a remarkable turn of events given what had happened just minutes earlier. Gomez trapped Sanchez against his own corner post and landed several solid hooks before the champion ended the exchange with a powerful right to the jaw that caused Gomez to slap on a clinch. Moments later, however, Gomez again positioned Sanchez in the same corner and connected with an uppercut to the pit of the stomach, a hook to the ribs and a right uppercut to the chin before Sanchez spun away. The round ended seconds later, and while Gomez still was in duress, he sent a strong message to Sanchez: I am willing to fight you to the bitter end, and that end is farther away than you think.

Sanchez began the third in boxer mode as he neatly nipped in and out of range, snapped jabs, fired singular counters and piled up points against the stalking Gomez. Still, the challenger’s pressure continued to demand a strong pace, and, from time to time, he trapped Sanchez against the ropes, dug hard to the body with both hands, and nailed Sanchez with the occasional hook. One got the sense that the fight had moved into its next phase; could Sanchez continue to dominate with his boxing skills, or would Gomez, having survived Sanchez’s all-out assault, produce a surge of his own that would test the champion’s reservoir of intangibles?

Gomez did his best to do just that in the third, and when he backed Sanchez against his own corner post yet again, it was he who got the better of the exchange and it was he who successfully slipped and countered. It marked a sea change in the narrative; for the first time in the fight Gomez showed he could compete well against this version of Sanchez and, in doing so, maintain the hot pace that best suited his game. Better yet for the 122-pound champion, it appeared Gomez had just won his first round.

But his success came with a price: As the round ended Sanchez landed two flush jabs to Gomez’s fractured cheekbone, whose swelling had worsened and was now accompanied by discoloration. The Puerto Rican’s deteriorating countenance reminded ringside scribes of a prediction Sanchez made earlier in the week: “You had better take your picture before the fight because after I get through with you, you won’t recognize yourself.”

The fourth looked much like the third, with Sanchez the swordsman picking away at Gomez’s wounds and the aggressive Gomez doing his best to work past Sanchez’s spears. In some ways, Sanchez-Gomez was channeling Ali versus Frazier; Sanchez was the balletic butterfly with the stinging straight punches while Gomez, despite sporting a horribly swollen face, plowed forward with full faith in his power and resilience. And, like Frazier-Ali I and Ali-Frazier III, Sanchez and Gomez fought with championship-level intensity and forced themselves to access resources beyond the physical. The final 30 seconds of the fourth produced the most sustained two-way action of the bout thus far and, in doing so, fulfilled the best visions of those who created the tag line “Battle of the Little Giants.”

The fourth looked much like the third, with Sanchez the swordsman picking away at Gomez’s wounds and the aggressive Gomez doing his best to work past Sanchez’s spears. In some ways, Sanchez-Gomez was channeling Ali versus Frazier; Sanchez was the balletic butterfly with the stinging straight punches while Gomez, despite sporting a horribly swollen face, plowed forward with full faith in his power and resilience. And, like Frazier-Ali I and Ali-Frazier III, Sanchez and Gomez fought with championship-level intensity and forced themselves to access resources beyond the physical. The final 30 seconds of the fourth produced the most sustained two-way action of the bout thus far and, in doing so, fulfilled the best visions of those who created the tag line “Battle of the Little Giants.”

The frenzied Gomez fired a right after the bell that ignited a brief but menacing stare-down – just the kind of mano-a-mano warfare he wanted. Though still behind on the scorecards, Gomez was riding a wave of momentum, and he sought to continue that trend in the fifth by backing Sanchez against the ropes and firing his Bazookas. Unlike the earlier rounds, Gomez’s punches were connecting accurately and with force while also doing a much better job of avoiding Sanchez’s counters.

“Gomez almost appears to have gotten his second wind,” noted Sheridan.

Indeed, he had, and despite a Sanchez flurry in the final seconds of the fifth – most of which was blocked or avoided — an argument could be made that Gomez had won at least two of the last three rounds (if not all three) with his effective aggression and improving defense. Even so, there were still 10 long rounds to go, and despite Gomez’s recent success Sanchez’s face was still clean, his stamina was rock-solid and his technical skill remained uncompromised.

Holmes sensed as much when he said this at the start of the sixth: “I don’t see this fight going about a couple of more rounds if Sanchez comes out and starts boxing, putting combinations together. I feel that he will stop Gomez.”

Sheridan’s response, however, illustrated that Gomez was still very much in the fight and that even if he lost his warrior’s reputation would remain intact.

“The sign of a true champion is one who could get off the canvas and come back and win a fight, and that’s going to take all the courage in the world for Wilfredo Gomez,” he said. “And he’s certainly shown us one thing: He has the heart of a champion no matter what happens tonight.”

The ferocity of the fifth was replaced by the science of the sixth as Sanchez boxed, circled and countered well enough to avoid being trapped the ropes and to keep Gomez at arm’s length. He was the one who began and ended most of the skirmishes and Gomez, now in recovery mode, was unable to shorten the distance or draw Sanchez into exchanges. Another negative development for Gomez was the state of his “good” left eye, which now sported bruising and swelling above and below it.

The seventh commenced with a role reversal as Sanchez confidently advanced toward Gomez, who sought to induce an exchange by backing toward the neutral corner post. But Sanchez was having none of it as he remained at long range and popped the Puerto Rican with jabs and counter shots. But midway through the round, Gomez broke through with his combination of the fight thus far — a clean right cross immediately followed by hook to the jaw that briefly buckled Sanchez’s legs. With that, the fight’s dynamic turned yet again as Gomez cut the ring off and connected with singular power shots while Sanchez calmly picking his spots – including a counter right to the chin that froze Gomez for an instant.

“Gomez is really a determined fighter,” marveled Holmes. “He keeps pressuring the action all the way. He’s taking punches from Sanchez and he keeps throwing his own punches.”

And, entering the eighth, Gomez was still very much in the fight mathematically: Henry Elespuru had Sanchez up 67-66 while colleagues Duane Ford and Chuck Minker concurred with 67-65 tallies.

One look at Gomez’s face, however, illustrated the mountain he still had to climb in order to conquer Sanchez. The swelling from his fractured cheek was large enough to close his right eye entirely and the swelling above and below his left orb had tightened nearly as much. The scheduled 15-rounder had just passed its halfway point and Sanchez, who had completed 13 or more rounds in five of his six championship fights, looked as fresh and as unflappable as he had when he entered the ring.

Sensing the need to go for broke, Gomez attempted to draw Sanchez into a firefight, but the champion drilled Gomez with counters to the face and clamped on clinches when necessary. Shortly before the round’s midway point Sanchez suddenly pivoted away from the ropes, repositioned Gomez against the strands and connected with a hard right to the face that caused Gomez’s upper body to slump slightly. Sanchez then landed a lead right to the jaw, then another right that appeared to further distort Gomez’s already distorted face. Sanchez then nipped out a few inches, teed up Gomez with his extended left hand, and landed a crushing right to the head that had the half-conscious Gomez looking like a fly tangled in a spider’s web. That was enough to convince Sanchez to turbo-charge his assault, and that assault included a half-dozen more power punches that left Gomez on all fours.

The badly buzzed Gomez pushed himself up to knee and used the second-highest strand of rope to regain his feet by Padilla’s count of eight. Padilla looked intently into Gomez’s eyes, and Gomez non-verbally transmitted his physical state to the referee by leaning backward into the ropes and letting his upper body bounce off of them instead of meeting Padilla’s eyes with a determined stare. Padilla took the cue and waved off the fight at the 2:09 mark of Round 8.

Photo by The Ring Magazine/ Getty Images

The triumphant Sanchez was lifted skyward by his corner men and other well-wishers, then paraded around the ring on their shoulders as Gomez was tended by his handlers.

“I fought exactly according to my plan,” Sanchez said through a translator. “I really enjoyed fighting Gomez. In fact, I was so eager for this fight, I wish we could have gone 15 rounds.”

Gomez, whose right eye required 14 stitches, did not attend the post-fight news conference but had one of his lawyers, Gabriel Penagarciano, speak on his behalf.

“We have no excuses,” he said. “Sanchez is a great champion. When Wilfredo tried to come back between rounds, he felt the power of Sanchez’s punches.”

But just a few seconds later, Penagarciano did bring up the elephant in the room – the massive morning-of-the-fight weight loss – by stating “he was considerably weakened by the mandatory four-pound weight loss.”

As for Gomez, he also blamed the weight cut for his performance, but he later stated that the punches that led to the first-round knockdown convinced him he couldn’t win.

“After that punch, I wasn’t the same,” he told Giudice. “I felt that punch and my face started to swell up because I had to lose so much weight in so little time. This was when I knew that I couldn’t win the fight.”

After a pair of tune-up fights against Jose Gonzalez in January 1982 (KO 7) and Jose Luis Soto 42 days later (KO 2), Gomez returned to 122 and continued to defend his championship, extending his streak of consecutive title-defense knockouts to 17 – a mark that still stands today. The final entry was his classic 14th round TKO victory against bantamweight champion Lupe Pintor in December 1982, and he went on to win titles at 126 and 130 before retiring in July 1989 with a 44-3-1 (42) record.

Sanchez, whose cover photo on the November 1981 issue of The Ring bore the headline “Boxing’s New Conquistador,” shared the publication’s November 1981 Fighter of the Month award with Sugar Ray Leonard, then shared the magazine’s Fighter of the Year award with him after notching a December 1981 split decision over English challenger Pat Cowdell. Victories over Rocky Garcia (W 15) and Azumah Nelson (KO 15) – a late replacement for Mario Miranda – followed, and, at age 23, Sanchez was well-positioned to produce a long and historic run that he hoped would include a showdown with WBC lightweight titleholder Alexis Arguello.

But it was not to be; he was killed instantly just 22 days after the Nelson fight. At 3:30 a.m. on August 12, 1982, his Porsche 928 collided with a truck on a road leading to his training camp in San Jose Iturbide, located 160 miles north of Mexico City. He was survived by his 21-year-old wife Maria Teresa, and two young sons, 16-month Cristian Salvador and four-month-old Omar. The Associated Press voted Sanchez the third-greatest featherweight of the 20th century and he was a member of the International Boxing Hall of Fame’s Class of 1991. Gomez was voted in four years later.

Had Sanchez lived, he could have followed up on another one of his dreams.

“I always wanted to be a doctor,” Sanchez said. “They’re always clean and neat. Everybody respects the doctor, right? I mean, he is somebody important, right?”

Right. While fate prevented him from scaling his professional mountaintop and from experiencing the fullness of his boxing life, his career, though an unfinished symphony, still left a massive imprint. And a big part of that imprint was created by the signature performance of his career, a performance that still resonates four decades later.

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, West Virginia. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 20 writing awards, including two first-place awards, since 2006. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. as well as a panelist on “In This Corner: The Podcast” on FITE.TV. He is the author of “Tales from the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics” (available on Amazon) and the co-author of “Muhammad Ali: By the Numbers” (also available on Amazon). To contact Groves about a personalized autographed copy, use the email [email protected] or send him a message via Facebook or Twitter (@leegrovesboxing).

SUBSCRIBE NOW (CLICK HERE - JUST $1.99 PER MONTH) TO READ THE LATEST ISSUE